‘Hindu Love Stories’ is a collection of short stories selected from the Hindu epics, puranas and scriptures. That the title of the collection is Hindu Love Stories is significant. The author makes a bold statement by not using such neutral sounding terms as puranic, ancient Indian etc. This assertion lends integrity and directness to the narratives in the book. It also sets the stage to delve into Hindu philosophical concepts, at the peak of which are the four purusharthas, the primary aims of human life – dharma, artha, kaama, moksha, for in India, prema or love, has been rooted in dharma, is a means to gain artha, fulfil kaama, leading to the attainment of moksha.

In Hindu thought, love does not mean physical love or lust, something that is wrongly attributed as kaama, nor does it mean the romantic-pink candy floss romance. Love, be it worldly or for the divine, has dharma at its base, and ultimately leads to moksha, liberation. Love that is rooted only in pandering to the senses is of a base nature and the scriptures warn against getting sucked into this.

Hindu thought even gave equal importance to the feelings of man and woman in this dharmic love. Indeed, the Sanskrit word for sexual intercourse is sambhoga, which means to ‘enjoy together’ or ‘enjoy equally’. It can even be taken to mean ‘to become one in enjoyment’. Clearly, this indicates thought and deed of a higher order, rather than the basal satisfaction of the senses.

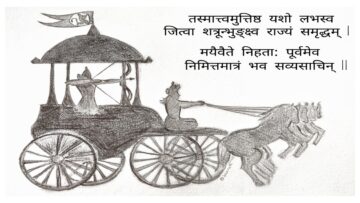

The present book, ‘Hindu Love Stories’ sub-titled ‘Dharmically Ever After’, takes a departure from the cliched ‘happily ever after’, for what is happiness if not fleeting? Bhagawan Shri Krishna says in the Gita, maatraasparshaastu kaunteya sheetoshNasukhadukhaah, aagamaapaayinonityaah taam titikshasva bhaarata [2.14]. It is for this reason that the stories of love in our spiritual texts talk of rising in love, and not falling in love. The author Aditi Banerjee delves deeper into this in the enlightening preface to her book. She clarifies that dharma is frequently misunderstood as either religion, or the path of renunciation and celibacy, which is the path of nivritti. The stories of love in Hindu spiritual texts demonstrate dharma by the path of pravritti, of following the path of dharma while being immersed in the material world. The way to do it is to be like a lotus leaf, which despite being in water, does not get wet –padmapatram ivaambhasa, as Bhagawan Shri Krishna states in the Gita, 5.10.

The author begins the preface with Saraswati vandana, and it is wonderful to see a contemporary work start with a prayer, something that was a regular feature in Indian language writing until recently.

The collection has 27 stories –I am not sure if it is a coincidence or whether the author intended it, but 27 are the number of nakshatras in Hindu astrology, which cover one lunar month. In Hindu thought, there is no beginning or end, everything is a continuous, ongoing cycle. So is it with the nakshatra cycle: after Revati, we come back to Ashvini. So is it with the stories of love in our ancient texts; there is no ’The End’, it is always a ‘dharmically ever after’.

The stories in the collection are grouped into nine categories, starting with Beginnings, progressing to Stories of Wooing and then to Sometimes Love is Fleeting, for it is, is it not? Then comes Kaama Too Must be Honoured, after which we have Devotion, and then Rising Not Falling. As prema ascends higher levels we have Sacrifice, then Separation ending with Leela. The story of Bhamati, the author’s favourite, finds place in a section of its own – the 10th section titled Bhamati.

Reading through the section headings and the titles of the stories in each, we find the entire cycle of love, starting with wooing, the first rushes of requited love, bliss of oneness, leading to trust and faith between the partners, progressing to devotion, which enables wilful sacrifice. Viraha or separation, a theme that depicts the heightened state of being in love comes next, after which we enter the realm of divine love in Leela. The story of Bhamati is the pinnacle of pristine, pure love, which has trust, devotion, sacrifice, leading to immortality.

Some of the stories, such as those of Satyavan-Savitri, Rukmini-Krishna, Satyabhama-Krishna, Sati/Parvati-Shiva are popular and many readers will be familiar with these. There are some stories such as Menaka-Vishwamitra, Pururavas-Urvashi that some readers may be aware of. The author has included some not very well-known stories such as those of Ruru-Pramadvara, Bhamati, Hemachuda-Hemalekha, Agni-Swaha and these were an eye opener. Even with the familiar stories, the author layers them with the dharmic context and it is a treat to read these in a different light.

The story of Savitri is an excellent example of this approach. Savitri, who brought back the life of her husband Satyavan, from the clutches of Yama himself is known to Indians. Most of us are familiar with Savitri’s devotion to her husband, and the clever boons that she asked from the lord of death, effectively regaining her husband, and her in-laws’ lost kingdom. However, few will be aware of the dharmic words of wisdom that Savitri spoke to Yama, that impressed him to grant her the boons in the first place. Savitri’s behaviour, her thoughts reflected in her words, establish her as a sahadharmacharini, the wife who walks the path of dharma with her husband.

The stories also break the false myth that women in Hindu stories are meek, submissive and ever-suffering. The stories of Savitri, who wrested her husband’s life back from Yama, Satyabhama who fought Narakasura to give a respite to her husband Krishna, apsaras Menaka and Urvashi, who once their assigned task was completed, directed Vishwamitra and Pururavas, their respective partners back on the path of dharma, and Leela who corrects her husband Padma’s errant ways, and other stories break these false stereotypes.

The women in these stories of love are intelligent, assertive, know what they want, and exercise their will freely, without succumbing to pressure, patriarchal or otherwise. Swaha, smitten by the resplendent Agni, does everything in her power, to get the man she loves; just as princess Savitri knowingly chooses Satyavan who only has a year to live, princess Sukanya chooses Rishi Chyavana who is aged and frail. None of these women were forced into apparently un-exciting marriages – they did so with choice and free will, and a sense of dharma.

Nor are these stories stereotypical of women being the sacrifice. In the story of Ruru-Pramadvara, Ruru brings back the life of his beloved Pramadvara from the clutches of a servant of Yama, much like Savitri reviving Satyavan.

The focus of the entire corpus of Hindu texts, be they literature or philosophical-spiritual, is the elevation of the being from body consciousness, the deha-bhaava to pure consciousness, the jeeva-bhaava and ultimately attain brahman, the state of unity, jeeva-brahma aikya, with the supreme parabrahman. The author has graded the stories in the collection in a similar fashion. The stories of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu and Vishnupriya, Bilvamangala Thakur and Chintamani and Leela and Padma similarly lead us away from the deha-bhaava towards jeeva-bhaava, hinting at jeeva-brahma aikya. It is not a surprise that the next section on sacrifice starts with Savitri and Ruru-Pramadvara, and ends with a story titled ‘The Dust of the Gopi’s Feet’, a touching story of extreme bhakti, of which devotion is only a poor translation. It is only with this bhakti that one can experience the ecstasy of the raasa-leela, when one achieves bhaava-aikya with the ishta-devata. In the absence of such bhakti, these stories will only appear as misogynist, patriarchal, and in the extreme, as is seen in many contemporary ‘mis’-interpretations, outpouring of excessive lust. The stories in this collection demonstrate that the reality is far from such incorrect interpretations, mischievous or otherwise.

Interestingly, the author has skipped popular love stories such as Dushyanta-Shakuntala and Nala-Damayanti. Of course, the corpus of stories of love from the Hindu texts is so vast that to even include a small percentage is an achievement. A collection such as this has to be of manageable size for wider appeal. The exclusion of some popular stories is therefore understandable. In fact, this makes space to include lesser-known stories, and that makes the reader richer.

While the author has contextually included concepts from Hindu philosophic thought, it is light enough to not scare away readers unfamiliar with these concepts. At the same time, it is deep enough to draw in the advanced reader who has more than a passing familiarity with dharmic concepts such as the purusharthas. That the stories are entertaining and instructional at the same time is indeed a commendable achievement. I hope that the author comes up with a follow-up volume to this collection soon.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.