A young boy insists that his 75-year-old grandmother pen down her memoirs. He tells her that the stories and anecdotes that he grew up listening need to reach a wider audience.

Devaki Nilayamgode, like a typical grandmother, cannot turn down her progeny’s requests and finally starts writing. Her first published memoir in Malayalam is titled Nashtabodhangalillathe – Without regrets.

Devaki also goes on to publish a second set of chronicles Yathra: Kaattilum, Naattilum – A Journey through Forests and Lands. Her memory is astounding. She now starts to write lucid details of her younger years inside an Illam, Namboodiri household.

It is very interesting to note that Devaki chooses to be not judgmental about the people and the events that have transpired in her life. She writes about the unfair treatment of women, particularly herself, without any sense of anger or ill-feeling. She also writes about Namboodiri rituals, customs, festivals, feasts, and the indigenous lifestyle of that period.

While she raises pertinent questions, she avoids any blame-game. She also demands fair treatment without any stridency. She chooses not to be bitter about anything. I will come back to these choices made by the author a little later in this article.

The memoirs garner much praise but also receive some scorn. Years later it is translated to English. ‘Antharjanam – Memoirs of a Namboodiri Woman’ – is the English translation of essays by Devaki. It is published by Oxford University Press.

Indira Menon and Radhika P. Menon have done an excellent job in ensuring that this little known cultural nugget of Kerala is now available to a wider audience. They have taken great care not to meddle with the narrative style or tone of the original work.

The book brings out the placid and calm narrative by capturing the nuances highlighting the original fierce quality.

Antharjanam – Sanskrit word that literally translates to “inside people or people who live inside”. Devaki herself is an ‘Antharjanam’ – singular noun as well as a collective noun for Namboodiri women.

Some even have it as their surname. For example, Aryamba mother of Adi Shankaracharya is also known by another name ‘Kaippilly Aryadevi Antarjanam’.

The essays, though personal in nature, provide an intimate peek into the author’s life i.e the early years of an Antharjanam between 1928-1950. The Antharjanams are called so because they were expected to stay in the inner quarters of the Illam at all times.

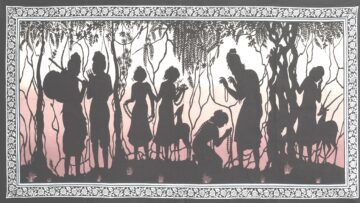

They could neither step outside the Illam without chaperones nor be seen by any other men. Whenever they stepped out, the Antharjanams were always cloaked and covered under a large cadjan umbrella – Marakkuda.

They were surrounded by chaperones shouting ‘yaa..hey…yaa…hey’ to alert the passers-by, and making people of other jatis keep away.

Antharjanams wore dull clothes and were discouraged from looking too attractive or applying artificial makeup. Devaki vividly describes the life inside Illam such as the daily rituals, the various festivals being celebrated, the seasonal vegetables/flowers, and food preparations.

Devaki finds beauty in simplicity and austerity. She talks about the month of Karkidakam, where girls smeared a mixture of fresh turmeric and castor seeds for a bath.

This was followed by a simple beauty routine of applying kanmashi-Kohl and chandanam-Sandal Wood paste to the face, and an adornment of ten varieties of medicinal flowers & leaves to the hair (Dashapushpam – karuka, choola, poovakurunnila,krishnakranthi, mookutti, moshami,nilappana,kayyoni, uzhinja, thiruthali).

Chapters titled, ‘A Group Dance’, ‘Visitors’, and ‘Clothes’, portray the innocent excitements of that time. With great attention to detail, she describes simple pleasures and joys. There are references to indigenous practices of harvest, storing clothes, utensils, and perishables. She recalls battling floods and epidemics.

There are many such riveting episodes in her book. Onne incident about the Namboodiris treating snake-bites is especially intriguing. There is also a brief mention of KP Namboodiri marketing his tooth powder,(still hugely popular Danatadhavanachoornam) by travelling on foot to remote villages.

Devaki maintains a tone of detachment throughout her memoir . This is especially evident in her references to people outside the Namboodiri jaati. The older women of the family have their hands full with all the household chores.

Babies and young girls are under the care of house helps. Devaki fondly recalls how these househelps – irrikanammamar stayed inside the Illam and took care of all the children’s needs. There is very little interaction with people from outside the community, apart from the irrikanammamar.

Devaki grimly narrates how one visitor to the Illam remarked that ‘it was difficult to distinguish between a cherumi, a crow and a buffalo’. She recalls that such a remark was endorsed by older women in her own family. Chapters like ‘Widows’, ‘Leavings’ make the reader cringe at these anachronistic practices and norms.

Devaki painfully describes the complete negligence of the women in a Namboodiri society. She narrates how the men were patriarchal to the hilt. In their large scheme of things, women served little purpose but procreation. They were not encouraged to read or write.

Always confined inside the Illam, their daily routine revolved around a hundred rituals, and a dozen baths. The birth of a male was celebrated but that of a girl child was never appreciated. There was also the rigorous practice of the dowry system. Devaki explains in detail the custom of priority given to the firstborn male in the family.

Only he was allowed to marry within his own community and that too multiple times. The other male offspring – Apphans, had to settle for Sambandham – a casual relationship based on consent alone, usually with Nair women. Apphans could continue to live at the Illam.

But, their partners and children could not set foot inside, and least of all have any claim on the ancestral property. She recounts how this bizarre custom gave birth to complex social arrangements and complete hegemony of the Namboodiris inside and outside the Illam.

In her memoir, she also reminisces some historical events. Most significant being the Smārthavichāram (inquiry into the misconduct of an Antharjanam) of Kuriyedathu Thāthri . Devaki ‘s comments on these two historical events are somewhat ambiguous.

Perhaps, conveying that her confined upbringing did not encourage her to think beyond the Illam and its restrictions. The translators note that this is a superb example of Devaki’s essential humanism.

Devaki witnesses the high point of the reformist era of Namboodiri community through the Yoga Kshema Sabha [YKS] under the leadership of V.T. Bhattathiripad. Devaki mentions Arya Pallom and other women who were part of the reformist movement with great admiration.

The YKS during their active years worked tirelessly towards the upliftment and betterment of the community. She describes the events that unfold with a strong sense of hope and gratitude for the Antharjanams. She also states that her marriage into a liberal household, the ‘Nilayamgode house’, as the turning point of her life. Her husband and in-laws encourage her to abandon archaic practices and move on with modern times.

It is a significant note here that the Namboodiri men were instrumental in bringing about reform within their own community starting from their homes. The last chapter in the book talks about the winding up of YKS in the 1950s. Her closing lines are mentioned below

‘Today, there is no sorrow specific to a Namboodiri family. It has the same joys and sorrows, the same anxieties and ambitions as any other family. Time, the great leveler, has ironed out most differences. Here, my brief autobiographical account comes to a close. The reason for it is obvious and simple – after this, there can be no autobiography which claims to be the first by an Antharjanams or exclusively about us”.

When I finished reading this book, I was overwhelmed with warmth and respect for Devaki. She comes across as the epitome of resilience. At the ripe age of 75, she lays her feelings threadbare and calls a spade a spade.

A life without the burden of judgment or rational analysis of the times. An innocent and poignant insider’s view. Seeing or taking life for what it is and thriving. Now, this an endearing and exemplary virtue found in women of substance.

I wanted to know more about Devaki. . Her memoirs received a large number of rave reviews. But, I also found a few vile ones. These reviews summarily dismissed the book as ‘upper-caste’ rambling.

One pointed out how there is little mention of people and culture of ‘lower-caste’ communities and another, an academic publication went so far to say “Antharjanam is conscious, deliberate and compulsive sketching of the Namboodiri culture as privileged.”

When I posted a short review in a closed Facebook group, one or two members commented that my review reeked of brahmin privilege and hegemony. This seemed a bit odd to me and I needed to understand this better.

I decided to read the book all over again specifically looking for “upper caste”, “privilege” and “hegemony”. I found none of that. Instead, I felt the need to call out some of the prejudices, intolerance and brahmin-bashing (brahminophobia?) masquerading as reviews or academic publications on this book.

At the outset, one must acknowledge the choice of an author while writing an autobiography. Devaki made a choice to be composed, dispassionate, dignified, and most importantly honest about how she must pen down her memoirs.

A choice not to cry foul, indulge in any sort of blame game. A choice that did not require her to check the right boxes of feminist theory in popular culture. A choice that no one can take away from her.

One review published in Academic Research Journals [ISSN: 2360-7831] categorically states that “Nilayamgode‘s work is a deliberate attempt of a glorifying image of herself and her class of people”.

I think that this statement is not only baseless but also serves to twist the cultural narrative of a community. Whether this is done for academic or political gains is anybody’s guess.

Now, it must be said that there is very little known or written about Namboodiri women. Lalithambika Antarjanam, is the sole literary figure who is always mentioned in any or all articles on the topic of Antharjanams. Her seminal work Agnisakshi won the Sahitya Academy awards and is brilliantly adapted into a movie by the same name.

The other popular reference of a Namboodiri woman is Kuriyedath Thāthri, a woman at the centre of a1905 sex scandal. Lalithambika has also penned the story of Thāthri/Savithri and her Smārthavichāram in her story Pratikara Devata.

Apart from these two, there is very little literature solely involving Namboodiri women. There is also a 2016 Sanskrit film critiquing the Namboodiri rituals which are not available online. It is important to notice here that all popular mentions of Namboodiri men or women are always in the context of their class structure, archaic practices, revenge, or rebellion.

Attributing every prejudice and hatred one has towards brahmins onto the Namboodiri community is highly inappropriate. There is no theme of rebellion or revenge in Devaki’s book. When wronged, some seek vengeance, some seek change.

Devaki instead of vengeance sought change and was lucky to be a part of the change that she wanted to see in her community.

It is also unnecessary and unfair to read the memoirs in the context of class structure or brahmin privilege. If anything, Devaki Nilayamgode’s memoirs serve as a shining beacon of resilience.

Devaki rightfully deserves her place in the line of stellar Antharjanams for writing this honest memoir without righteous indignation. No amount of ‘upper-caste’ bashing can take this away from her. Her choice of title ‘Nashtabodhangalillathe’ represents this resilience without mincing words.

A wonderful interview of Devaki Nilayamgode is available on YouTube here:[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=le6A0Z4Spao ]

A copy of Antharjanam is available for purchase here

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.