Let me start by telling you a story on how wondering about our past can lead to delightful discoveries. Janaki Ammal, my grandmother had once said, “When I was small, elders used to talk of some relatives from our village who had gone on a Kasi Yatra and didn’t return for more than a year. And then one day, they returned – not all, though, but most. Some had died and some settled at various places along the way.”

My grandmother was born in 1900 in Thodur, a village near Tiruvvallur in north Madras. The once far village, is now a suburb of Chennai, the new name of Madras. She was married at 11 to an 18-year-old boy from my village Damal, near Kanchipuram, which was to become her home.

She probably heard of the Kasi Yatra during her childhood in Thodur.

When I nudged her to tell me more about the yatra, she recalled overhearing tales of flaming torches to light the way, armed escorts, cooks, palanquins, their bearers, and porters for luggage. She had heard that a proposed pilgrimage would be announced in proximate villages, and desirous people would sign up. They were mostly elderly who had vowed to visit Kasi at least once in their lifetime- whether or not they returned. Many elderly ones would bid a veiled last goodbye to their loved ones. I imagined them to have been misty eyed, but of sturdy determination to go on the Yatra.

For the young boy I was, this was a thrilling nugget – “They spoke of a young man of my village,” grandmother said, “who was taken by pilgrims because he was fearless of thieves and animals.”

Memory of this conversation – in the 1950s – stayed with me as I grew up, left home and travelled the world. I would often retell this story in small groups, embellished I confess, with details from my own imagination – “They all walked and took turns to ride in the palanquin,” I would say, as though I had personal knowledge of it. “They stayed at well known shelters along much travelled trails.”

I added guides and bullock carts serving in relays. I made the highwaymen a polite lot as long as they collected a toll per head.

I was anxious I was not found out to have made up my tales. My listeners almost always bought into them.

Quite early into my narrative, I would as a precaution ask if anyone had similar stories to corroborate mine. I found none, and that emboldened my creative liberties with the stories.

Working the dates, I guessed grandmother may have been referring to events of 1850s, the times of her grandparents. My research got no further. The Internet was decades away. I continued to share imagined but plausible stories of those hardy folks who walked their faith, despite the odds they faced.

Grandmother died in 1999 – four months short of a neat 100 years. She had been an enthusiastic raconteur. And authentic one too, given that the details of her story, though few, seldom changed – unlike mine, as I must sheepishly confess. My itch to know more remained but subsided over the last two decades since she died.

There that rested, until I discovered a remarkable man called Enugula Veeraswamy.

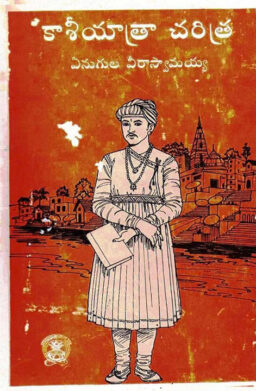

One day in 2020, while idly browsing the internet for ‘Kasi Yatra in 1800s’ I was led to a book called ‘Enugula Veeraswamy’s Kasi Yatra Charitra’. It is the travel diary of Veeraswamy, who undertook a Kasi yatra in 1831. His journal is deemed the first modern Indian work in the genre of a travelogue. It was published in 1973, by the Andhra Pradesh government. The book is a free download from the site of Rare Books Society of India.

I froze reading this – “The round-trip lasted 15 months.”

And at once I heard my departed Grandmother say it again: “… relatives from our village who had gone on a Kashi Yatra and didn’t return for more than a year.”

Veeraswamy was likely born in 1780. He lost his father when still young, but that didn’t deter his remarkable achievements. By 12, he was fluent in English. Besides his native Telugu, he knew Tamil and Sanskrit as well. He was a pious Brahmin but not an uncritical Hindu. He rose to be the Chief Interpreter of the Supreme Court of Madras Presidency. He lived in Tondiarpet area of Madras city.

I did some quick research. I drew a circle of 60 km radius, centred on Thodur where my grandmother was born. Both Tondiarpet and Damal fell within the circle.

In that moment it all fell in place for me. The choice of 60 km was based on my grandmother saying families in those days seldom made marriage alliances with villages that were beyond a daylight run of a bullock cart, nor should the path require fording of a river.

It was quite plausible for news of the planned pilgrimage to have reached Thodur quickly and for villagers to have signed up. The book says Veeraswamy travelled with a large entourage of his family, palanquin bearers, porters and probably cooks and servants as well. They carried tents and pots and pans.

But were there others? Other pilgrims?

A reference in page 67 had the evidence I was seeking: “… besides his womenfolk, many pilgrims were among the entourage.”

In an academic paper on the book, available on Archive.org, I read his entourage was 100 strong.

There! I was now certain my forebears were part of this or another yatra. My fantastical imaginations could now be defended with confidence. I had a book to throw at disbelievers of my story. Veeraswamy had arrived to validate my long running yarns.

The book is full of vivid descriptions of people, local histories, economy, customs, oddities, and of nearly every temple he passes by.

Not for nothing is it deemed the first authentic travelogue by an Indian in modern times.

By an arrangement made with a friend before he left, Veeraswamy mailed him a report every day of his travels detailing all he saw and heard, and narrated customs, castes and habits of people. He also expressed his opinions on places and practices, rites, philosophy, theology, astronomy and sociology, for Veeraswamy was a very learned man. The book was a compilation of his mails.

The group, probably a hundred strong, reached Kasi travelling through the centre of India via Hyderabad, Nagpur, Madhya Pradesh and returned via Bengal, Bihar, Odisha and Andhra.

Let me leave you with an extract to whet your appetite to download and read the book. Below is a mail on a day in their return journey. This description makes me conclude that it was more of an expedition than a pilgrimage:

Page 177: “4th June, 1831:….

…Getting up at an early hour of six we went to Baghuna and reached there by nine. It is eight miles from here. There’s a road leading to this place. We crossed the river Damodar by boats. Since we were carrying eight pots of Ganges water, two unused tents, medicine boxes and other luggage loaded in two carts with us, it became very troublesome to cross these rivers. I thought whoever keeps with him carts on a journey like this will definitely be plunged into the evil influence of Saturn”

No trace of any of those ordeals in his last entry in the journal:

“I arrived at my house and garden at Thandayarapeta, which is four miles from Chennapatnam. It is a sandy track. A pleasant sight to look at the wide roads and choultries on either side of our way. I can take the severest oath and say the God Almighty can make a Mount Meru out of a mere blade of grass.

“It is exactly fifteen months fifteen days and fifteen minutes to reach my native place since the moment I left…”

Beatitude appears to have overwhelmed him.

There remains a point to be made before I shake off the spell cast on me by the remarkable man.

How much we end up missing by our neglect of many stories our elders carry in their minds and hearts. It was usual to listen to their old time tales, when I was small. I doubt if that practice endures.

Old people are willing tellers of tales. I once began a project to publish what anyone over 60 had to say in response to a single simple question: “Tell us about your parents and grandparents and your childhood.”

That will get most elders going. Their stories will never fail to engage you, though many were likely exaggerations.

I called the project ‘Memory Speaks’. It ran dry after a few contributions, which were delightful reads nevertheless.

If I were to resume it today, I would do it as a collection of audio files, using a mobile phone fitted with a reasonable quality mike. A great enterprise in oral history will evolve, for everyone to enjoy and ponder.

The history of a civilisation is not so much of its kings and leaders, but of how its people coped and prevailed.

Both Telugu original and English translations of the book can be downloaded for free from rarebooksocietyofindia (dot) org. Search for Enugula Veeraswamy.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.