I have heard it said that if you truly seek an answer to a spiritual question, you’ll invariably come by a Guru’s wisdom.

This is my story of such a discovery.

For forty of my 75 years, my work has had something or the other to do with the earth, plants and water. I have spent most of that time with rural people who work with their hands.

Almost daily, I was witness to their Hinduism in actual practice- spontaneously, consistently and without question. Things were done instinctively.

A workman would touch the soil before starting work. They would start the day after seeking to be blessed by their work tools, be it a trowel, a mattock or a saw. Many would take the first fistful of food to their bowed head before eating. Work on a area was always begun at the North East corner. A peepul tree was never to be cut. Most knew when it was likely to rain, what crop suited the time, when the moon began to wax and when to wane. It was best to sow seeds at amavasya and soon after. Steps in a stairs and pillars in a verandah had to be odd numbered. Most everyone knew basic arrangement of living spaces in a house. And of course, plenty of agreement on what was good to eat, for whom and when.

These and more, I could narrate here but that’s not the point of this article.

What struck me was a great rooted-ness in the very soil and a connected-ness with the space around us. “Religion’ was not something apart that you go somewhere to practice. It emerged in everything they did. Every practice seemed to be based on a great conviction.

No verse from any book gave them instructions. Their response seemed driven by an unspoken fundamental belief.

What was it?

Years rolled by without an answer.

Then, about 15 years ago, I chanced upon a writing of Swami Vidyaranya. Within an hour of reading this immortal Guru’s words, I was awakened to the rigour of the framework on which Hinduism is mounted.

Let’s briefly look at this great mind’s mortal life. Madhava and Sayana were born in an impoverished but learned family of Brahmanas in Warrangal in Andhra country. It was around 1300- pretty recent, you’d say on the vast Indian timeline.

It is said Madhava, the elder had prayed for long for relief from his unbearable poverty. Eventually he heard the Devi whisper to him that he shall not have her darshan or grace ‘in this birth’. Disgusted, Madhava took sanyasa and walked away. At once, the Devi appeared to him – to his huge irritation.

‘Go away,’ he said. ‘I am a sanyasi. I want nothing from you anymore.’

She chuckled and said:”Because you want nothing, you shall have everything!”.

Madhava, now Swamy Vidyaranya, became instantly omniscient. He wrote on ‘every conceivable subject: aesthetics, ethics, civics, morality, dharmashastra, religion, medical science, anatomy, physiology, metaphysics, epistemology; there is nothing on which he has not written.’

Incidentally, it was Swami Vidyaranya who spotted the promise in young Harihara and Bukka and mentored them to found the Vijayanagara empire. He continued as the empire’s minister, making Hampi a great seat of learning. But that’s another story.

The book that drew me to him is his work called Panchadasi. In it Swamy Vidyaranya is said to have captured the essence of Vedanta through his exposition of several Upanishads.

In 1989 Swami Krinanandaji Maharaj gave 42 discourses on it in English. I directly landed on the section on Pancha Mahabhuta Viveka, MaharajJi’s 7th Discourse.

He takes a single line of SwamiJi’s

Śabda-sparśau rūpa-rasau gandho bhūta-guṇā ime, eka-dvi-tri-catuḥ pañca guṇāḥ vyomādiṣu kramāt

…and expands it as follows:

“Only one quality can be seen in space: it can reverberate sound, but we cannot touch it, taste it, smell it… Space can only cause an atmosphere for creating a vibration of sound; so, as nothing else is possible there, Sound alone is the quality of space.

But of air, there are two qualities: air can make sound, and also it can be felt. It can be touched. Sound is the quality of space; sound and touch are the qualities of air.

But fire has sound, touch and has form, as we can also see it.

And water: we can hear its sound, we can touch it, we can see it, we can taste it. But we cannot taste fire, taste air, taste space,

Earth has five qualities: it can create sound, it can be touched, it can be seen, it can be tasted, and it can be smelled. Smelling is the quality of only earth

…so Earth has five qualities, Water has four, fire has three, air has two, and space has only one quality.”

I stopped right there. The utter simplicity of the declaration stunned me.

‘Is that all there is?,’ I asked marveling.

The answer seemed to be,’Yes, and that’s all that’s needed to explain the whole Universe’

This statement of what constitutes the Universe seemed a sufficient enough basis for a whole belief system.

Swami Vidyaranya had named them the Pancha Maha Bhuta. I took to calling them the Five Grand Spirits. [-rather the usual ‘Five Elements’, for a reason I shall explain in the end]

The moment of discovery, that from a vast brooding void, come all perceptible reality can be a very exciting one.

That moment, for me at least, was the one when I began my rediscovery of my Hindu-ness.

I found no need of a sloka or a murti or a manual or any further revelation.

Everything was orderly laid out.

The excitement of a discovery usually urges you to linger in it, to savour it.

And that’s how I chanced upon this blog, which translated a hymn from Taittriya Upanishad as follows:

From divine soul, verily,

space arose;

from space wind;

from wind fire;

from fire water;

from water the earth;

from earth the herbs and food;

from food semen, and

from semen the person/purusa

This hymn took me to manifestations like Food and life forms that are replicable objects. The five spirits are not readily manifest or they are as they say, ’not gross’. But here were tangible objects, life and food. They arrive almost like objects out of ‘nothing’ as from a conjurer’s hands.

This explained my fellowmen’s simple reverence for nature, food and life. They realized in awe, their dependence on unseen spirits that enveloped them.

They needed no murti, mantra or manual to ‘get’ this.

To put it in another way, even if all temples, murtis or art disappeared a Hindu’s sense of connected-ness with the whole would endure.

Though everything stems from the Five Grand Spirits, the arts, architecture, philosophies and rites did eventually arise due to humans, based on the five spirits

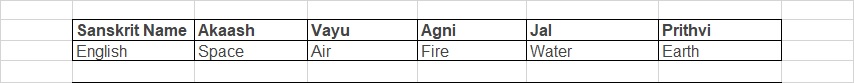

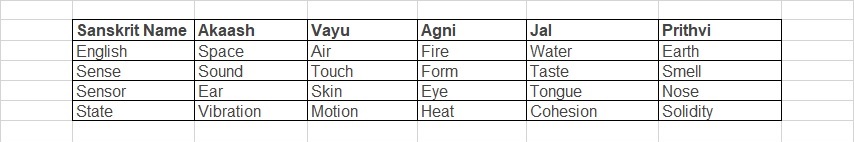

Let’s lay out what we have seen so far:

They were then mapped to senses and organs:

From an old discussion board I found more associations. All the following from a single post there:

Significantly, in the above list, only 5 Chakras are mapped to locations in human body. Of the seven Chakras, the two highest, Sahasrara [thought, mind] and Ajna [third eye, intuition] are too subtle to capture.

From here Indian imagination took off creating rites and practices, in other words, its culture itself.

In Tamil country from which I hail, there are 5 grand temples, each dedicated to a Mahabuta.

At Chidambaram, a vacant room represents Space. At Sri Kalahasti, a flickering lamp testifies to the presence of Wind. The temple Tiruvannamalai sits at the foot of a hill that sports a giant flame every year. At Tiruvanikkaval an aqueduct conveys Water constantly over the Lingam. At Kanchipuram the Linga at Ekamabreswarar temple is made of Earth.

It is said that those in tapasya move from one temple to another in the above order evolving their sadhana. Sri Muthuswamy Dikshitar [1775-1835] visited each of the temples, and composed and sang kritis in their honour. To this day, they are part of performing artistes’ learning list.

Here’s a fine article on the mapping of Pancha Mahabhuta with temples and music

Pilgrims- a majority of whom are not formally learned in our philosophy – get to hear of the dominance of Mahabhuta over the Universe. They develop an awe and reverence for them. It is this that I had been witness to in puzzlement.

I could go on extending my chart finding equivalences. There are many sources like this if you want to go further.

I decided to stop there. And so, here’s my final list:

The basis of Hinduism is not any book. It is based on a conviction of how Five Grand Spirits interplay to create the material world. Murtis, mantras, legends and rites are all means to understand, communicate or reinforce the idea of Pancha Mahabhuta.

Advaita Philosophy quietly and simply asserts that at the subtlest level there is ’nothing’ but a vast oneness. I visualise the arrangement like this: If I ascend from Earth and journey past Water, Fire and Air, I’ll leave them all behind me and arrive to gaze at a great reference-less void. Here, I have no identity, nor do I need one, for I have nothing to separate myself from.

It is my Hinduness that makes the visualisation so effortless, so without conflict with any prescribed unquestionable book.

I am free -indeed, encouraged- to explore and discover for myself.

I am no scholar. My engineering training for the sea was more as an apprentice in harbour workshops than in classrooms. My work at sea was akin to a well-trained labourer’s, a technician at best. For the last forty years, I have found happiness working barefoot and hands-on in fields.

Along the way I decided my swadharma is a Sudra’s.

Still, the engineer in me has always sought parts that fitted and worked predictably. It sought order that was elegant and minimal. And of course there has always been that search for a Theory of Everything!

My discovery came to me easily without any grounding in rigorous scholarship. I have not read anything I have stated above in the original. It’s is the result of shallow searching and gathering that most of us do in these times.

Nevertheless, I was led to an original discovery all my own, arising out of a puzzlement.

It was this:

In so far as I could tell, the concept of Pancha Mahabhuta was originally articulated in Upanishads, going back to many thousand years. I translate bhutas as ‘spirits’ rather than ‘elements’. I shall explain why, in a moment.

In the world beyond India, the preoccupation was with four ‘elements’. Akaash had not occurred to them. They were content with the more sense-perceptible, air, water, fire and earth. Admittedly, in India too for the Charvakas, what was not palpable did not count. But they never prevailed over the Vedantins.

In Greece, Empedocles [490-430 BCE] asserted Nature had four ‘roots’. Aristotle [384-322 BCE] seems for the first time to be nagged by a need for a ‘fifth’ element. It is only from Xeno [320-275 BCE] that a fifth element gained regular mention though not assigned a crucial role. Were they prompted by some knowledge of Indian thinking? We’ll never know. They just tagged it Aether and went about playing with their original four to construct a physical reality.

My puzzle was this: How was it for our ancestors, Akaash held a supreme place, from the very time of conceiving the Pancha Mahabhuta?

Then it occurred to me.

It is only on our planet that existence of air, fire, water and earth is a certainty. But it is only Akaash that pervades and embraces the entire Universe and all bodies in it. Without Akaash, what we’d have is a world-view but not a universalism.

This realisation, based on my superficial adventure of discoveries, left me in adoration of our grand rishis! I could not but observe how latter day prophets who went on to found Christianity and Islam expose their limitedness. To them the world was created for man at a precise time. Their gods require unquestioning acceptance of their statement about what life was about. Their centrality is human comfort. For Rishis, it’s the Truth that must withstand testing by anyone.

Advaita had no problem co-existing with Charvakas or Sankhyas.

‘Check for yourself and go with what feels complete,’ was the offer and the challenge.

I am a happy man resting in my understanding of Pancha Mahabhuta,

I am in deep veneration of its doctrine.

Later I longed for a Murti though, to worship Pancha Mahabhuta. How might I do that?

I realised my water pumping windmills had captivated me. I suddenly understood why.

My windmill became my Murti.

Once a year, at Ayudha Puja, I construct a makeshift shrine at the foot of its tower, and prostrate sashtanga in thanks.

I then silently address my Murti, as follows:

You stand tall, thrusting into Space

And you spin in the Winds.

Gaining power as though by Fire

You reach deep into Earth

To fetch up Water

As gift for me and my work

From one who loves me.

I thank you for your embrace.

Bless me.

Nurture me.

image credit: picxy

(This article was published by IndiaFacts in 2017)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.