Sanskrit has a tradition of poetry spanning several millennia. While today many people associate the language with only religious or ritualistic texts, the spread of subjects sanskrit poetry covers is very vast. Romance forming a big part of it can be easily understood when we consider Sringara, one of the nine rasas (sentiments) of poetry (or life, for that matter) is considered as “rasa-raja” – “the king of sentiments” by all traditional commentators of Indian poetics and dramatics.

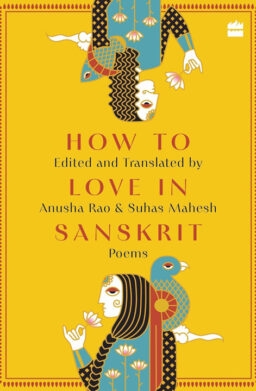

This year’s Valentine’s day offering by HarperCollins, “How to Love in Sanskrit ” by Anusha Rao and Suhas Mahesh is a collection of poems related to love, translated from Sanskrit to English.

The authors state the intent of coming up with this book clearly in their introduction, aptly called “Translator’s Workshop”, and agree that translation is largely a game of compromise, because of how languages work. But thankfully, they have not compromised much in “How to Love in Sanskrit”. In their own words, “even though a ship load of sanskrit poetry survives, only a bucket’s worth is translatable to English”. The authors have taken their source material from more than 80 original works in ancient Indian languages, and perhaps examined many times more, to select the final 80. In addition to Sanskrit, they have taken verses from Prakrit, Pali and Apabhramsha, the last of which is a precursor to some of the languages spoken in North India.

Translations from Sanskrit to English are indeed tough. They pose a challenge much harder than faced by a writer when Sanskrit is translated to other Indian languages. A major problem in writing a book as this is finding the right original verses that make good translated verses, and here the authors have scored high marks. You will be amazed to see that in their little “Translator’s workshop”, Anusha and Suhas have examined many excellent verses, as evidenced by the bibliography, only to discard the bulk of them because they are not translatable in the original context, or they cannot be set in the present day context for reader’s appreciation.

In “How to Love in Sanskrit”, the authors have adopted a minimalist approach to translation. In many places, they have taken the creative liberty to change the setting, context, and other details in the original verse to make it more readable as well as relatable to current-day readers who likely prefer English as their first language even if it is not their mother tongue. The vocabulary is thus simplified for a better appeal and appreciation by contemporary English readers, who may not be aware of the ways of sanskrit poetry, than sticking to the original expressions in the sanskrit poems. Having seen some other translations where the translators have failed to capture the essence of the underlying poetry, many times producing disastrous outcomes, I would like to congratulate the authors Anusha Rao & Suhas Mahesh for a job well done. Some examples from “How to Love in Sanskrit” will be provided later in this article, to illustrate these aspects.

Intentionally the translators have left the meter and sound, which are a very important part of the originals in Sanskrit. Although this has mostly worked out well, I must say it missed some of the charm. If they could have used some of the metrical lyrical translations, in some of the forms that are suitable for English, at least for some of the verses, it would have provided some ideas of the sound effects possible with Sanskrit poetry. Such translations have been tried by a few authors earlier, and in my opinion, they do well when within a limit suitable for the English language.

The book is split into sections, very catchily named as “How to Flirt”, “How to Keep it a Secret”, “How to Daydream”, “How to Yearn”,“How to Quarrel”, “How to Make Love” , “How to Make it Work” “How to Break up” and “How to Let Go”. There are a total of 218 translations in “How to Love in Sanskrit ”, mostly of verses, and a few short prose passages as well, falling into their theme. The authors have picked these from sources far and wide, including the Veda, Ramayana, works of ancient poets like Kalidasa, Magha, Sudraka to current day poets such as Shatavadhani R Ganesh & Prof Balram Shukla, well known anthologies such as Subhāṣitatriśati, Saduktikarṇāmṛta, Sūktimuktāvalī Amarukaśatakam, and Prakrit works such as Gāhā Sattasaī (Gāthā Saptaśatī) and Āryāsaptaśatī.

The original Sanskrit texts are given in the appendix in Roman script with diacritics. While this works for most readers, personally I felt it would have been convenient for those who know a little bit of Sanskrit to have the originals as in the footnote on the same page, and in Devanagari script. One thing I would have done differently is not to use translated names while citing Sanskrit works. While “Buddha Charitam” as “The Story of Buddha” and “Amarukaśatakam” as “Amaru’s Hundred” are passable, “Nagānanda” to “Joy of Serpents” or Manasollasa to “Hearts Delight” do not cut it. Also, little more extensive footnotes would have helped many readers.

But that apart, the book is highly readable, and as most such translations go, does not demand you to go from beginning to the end. You can just open a random page, and enjoy the poem. I would like to cite a few memorable translations from the book that I enjoyed very much along with some observations.

HLS, #3

Why I am an atheist

When the creator made her

if he had his eyes open

could he have let her leave heaven

Surely not.

If he had his eyes shut

could he have achieved such perfection?

No chance.

Therefore it is proved

that the Buddha was right:

There is no creator.

The above is a translation of the following verse by Dharmakirti

याता लोचन-गोचरं यदि विधेर् एणेक्षणा सुन्दरी नेयं कुङ्कुम-पङ्क-पिञ्जर-मुखी तेनोज्झिता स्यात् क्षणम् ।

नाप्य् आमीलित-लोचनस्य रचनाद् रूपं भवेद् ईदृशं तस्मात् सर्वम् अकर्तृकं जगद् इदं श्रेयो मतं सौगतम् ॥

[सुभाषितरत्नकोषः ४४०]

The translators have left out the elaborate descriptions of the subject कुङ्कुमपङ्कपिञ्जरमुखी, एणेक्षणा सुन्दरी (“doe-eyed damsel with a face with radiance of reddish hue resembling slush of saffron flowers”), but jump directly to the message of the unbelievable beauty of the girl the poet is describing.

HLS #8

When Looks can Kill

The doctors say that only poison

can counteract poison.

Save my life-

look into my eyes again.

The original verse is

दृष्टिं देहि पुनर् बाले! कमलायत-लोचने! ।

श्रूयते हि पुरा लोके विषस्य विषम् औषधम् ॥

[शृङ्गारतिलकम् १५]

The above verse also , you can see how the translators have left out the descriptions such as “कमलायतलोचने” – girl with wide eyes like lotus petals – but instead have gone for a more straight approach.

HLS #17

Why won’t you like me back?

How skillfully

The Love God launches his arrows!

He strikes me

squarely in the chest

But doesn’t

So much as touch you

though you’re right there

in my heart.

The original verse from Subhāṣita Sudhānidhi or Ambrosial Ocean of Verse, as the authors call it, by Sāyaṇācārya, the great Bhāṣyakāra of Vedas is below.

पश्यायताक्षि! भुवन-त्रितयैक-जिष्णोः शिक्षा-बलं धनुषि शम्बर-शासनस्य ।

भित्त्वा ममैव हृदयं हृदये निविष्टा बाणा यद् अत्रभवतीं न खलु स्पृशन्ति ॥

[ सुभाषितसुधानिधिः ३२.७]

For instance, in this verse from Subhāṣitāvalī [, one can see how the situation has been changed to contemporary times.

“इदं कृष्णं” “कृष्णं” “प्रियतम! ननु श्वेतम्” “अथ किं” “गमिष्यामो “यामो” “भवतु गमनेन्”“आथ भवतु” ।

पुरा येनैवं मे चिरम् अनुसृता चित्त-पदवी स एवान्यो जातः सखि! परिचिताः कस्य पुरुषाः ॥

[सुभाषितावली ११३८]

HLS #196

Who understands men?

‘Isn’t this black?’

‘Yes, seems like it.’

‘Actually, it’s white.’

‘Oh yes, I see it now.’

‘We should get going’

‘I’ll get the keys.’

‘Or we could stay awhile longer.’

‘ I’ll grab another drink.’

The man who so tangoed

in perfect sync with me

has now turned a perfect stranger.

Does anyone really know men?

Having shown how the translations are made more readable and enjoyable, by changing the context, here are a few more that I picked for the readers, where the verses have no change in context. I have chosen not to cite the originals for these.

HLS #34

Air of mystery

Silly girl,

Don’t reveal all in love.

Some things are shared

and some should stay mysteries.

Even Parvati

Who shares half of herself with her husband

only shares the half.

(Translation from one of the author’s (Suhas Mahesh) own verse)

निह्नवनीयं किञ्चित् किञ्चिन् मुग्धे! प्रकाशनीयं च ।

संविभजति पत्यार्धाद् अधिकं न नगाधिराजतनयापि ॥

HLS #186

Happily never after

He’s handsome, they all say.

But frankly

I don’t care much for him

because he’s my husband.

Would you enjoy ambrosia

if you had to drink it every day

on the doctor’s instructions?

(From Arya Saptashati)

सुभगं वदति जनः तं निज-पतिर् इति नैष रोचते मह्यम् ।

पीयूषे ऽपि हि भेषज-भावोपनते भवत्य् अरुचिः ॥

[ आर्यासप्तशती ६७१]

HLS #85

Loving from a distance

Fly, O wind!

Touch Sita

then touch me again.

In you, I’ll find her caress

and our eyes will meet

In the moon

(From Valmiki Ramayana)

वाहि वात! यतः कन्या तां स्पृष्ट्वा माम् अपि स्पृश ।

त्वयि मे गात्र-संस्पर्शः चन्द्रे दृष्टि-समागमः ॥

[ रामायणम् ६.५.६]

The book is published by HarperCollins and is being launched on Feb 14th, 2024. You can purchase a copy here and my Kannada translation of Amarukaśatakam can be purchased here.

A note by the editorial team :

Brevity is a hallmark of Sanskrit language. Indeed known for its conciseness and precision, the beauty, grammar, and structure of Sanskrit allows for complex ideas to be expressed in relatively few words, making it a language that is both poetic and efficient. Sanskrit Kāvyas are capable of transporting a rasika to ancient Bhārat’s rich cultural tapestry, offering insights into human emotions and life of times bygone. At the same time, their inherent appeal resonates even to this day. In this book, the authors have taken a lot of creative liberties to make the book more accessible and less intimidating to readers who may not have a clue about the world of Sanskrit Kāvyas. The credit for allowing such creative liberties must also go to the timeless appeal of Prakrit and Sanskrit Kāvyas and aesthetic tradition of Bharat.

Sanskrit is revered as deva-bhāṣā, yet when śṛṃgāra rasa fills a lover’s heart what pours out as poetry is a pure elixir of intoxicating emotions. ‘How to flirt’ when love springs like a delicate leaf, ‘How to Make Love’ when summer’s warmth ignites high passions, ‘How to Make it Work’ when the autumn’s hues dim the love’s light or ‘How to break up’ when the wintry chills refuses to thaw the feelings. Whatever may be the season of love, its essence is eternal.

Indica Today also loved the random but relevant pop culture references liberally sprinkled across the poems. Anusha Rao and Suhas Mahesh have attempted to bridge the gap between past and present by showing deep-rooted respect for literature in ancient Indian languages while revitalizing them for modern readers. We laud the efforts of the author-duo for this novel attempt.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.