Jayati Te’dhikam Janmā Vrajaḥ |

Śrayata Iṅdirā Śaśvadatra hi ||

-Verse 1, Gopīgītam, Adhaya 31, Daśama Skandha, Srīmad Bhāgavatam

The above lines vividly illustrate the greatness or Mahātmya of Vraja as they state that it was because of the birth of Lord Kṛṣṇa in the land of Vraja that its glory increased manifold and Iṅdirā or Lakṣmī made Vraja her eternal abode. It was because of the prākaṭya of Śri Kṛṣṇa that the land of Vraja attained unprecedented prosperity.

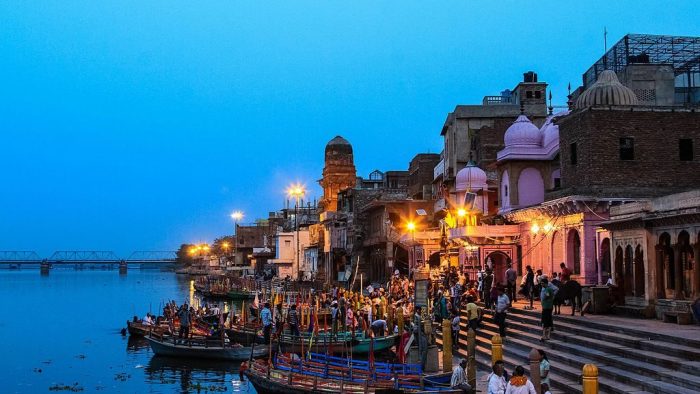

The city of Mathurā on the banks of the river Yamunā in western Uttar Pradesh and its surroundings are traditionally well known as the land of Vraja. In the modern context, the region of Vraja today covers the entire Mathurā district in western Uttar Pradesh, southern Haryana, and northeastern Rajasthan.

Though the city of Mathurā is not mentioned in the Vedas properly, the term Vraja does appear. Vraja signifies a sense of movement and denotes a settlement of pastoral groups. Today the entire city of Mathurā and her neighborhood is completely haloed with its association with Śri Kṛṣṇa who was born in Mathurā and spent his childhood and early youth in Gokula and Vṛndāvana. One of the early literary references to Mathurā is in the Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇa.

In the Uttara Kāṇḍa of the Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇa, Śatrughna who after killing Lavaṇāsura established a city called Madhurā or Mathurā describes the greatness of the city in the following words-

Iyam Madhupurī Ramyā Madhurā Devanirmitā |

(70.5, Uttara Kāṇḍa, Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇa, Gitā Press Edition)

The above line ascribes a divine origin to Mathurā. Mathurā is mentioned a number of times in later texts like the Harivaṁśa which is the khila or appendix text of the Mahābhārata as well. In Buddhist texts like the Aṅguttara Nikāya, Mathurā features as a capital of the Mahājanapada of Śurasena which was the seat of power of Andhaka Vṛṣṇis.

If we consider the available account of Megasthenes who visited India during the reign of Chandragupta Maurya (4th century BCE) as valid, Mathurā was a flourishing urban center at that time and known for its association with a God who was, according to Megasthenes like the Greek god Herakles. This god is generally identified with Kṛṣṇa.

From the Mauryan times onward Mathurā began to emerge a major center for religion, art, polity, and economy where a number of sects like Bhāgavatism (the original sect of Mathurā centered around Vāsudeva Kṛṣṇa), Śaivism, Buddhism and Jainism including the folk cults of Yakṣas and Nāgas flourished simultaneously.

The archaeological evidence like the numerous remains of monasteries and shrines scattered throughout the Vraja region and the great number of sculptures discovered from these remains bear testimony to this.

On the basis of archaeological evidence we can state that in the Kuṣāṇa (1st-century CE-3rd century CE) and Gupta (4th century CE- 6th century CE) periods, Mathurā was one of the leading religious centers in India and a site equally sacred to Hindus, Buddhists, and Jainas.

Apart from the Itihāsa-Purāṇa literature, there are references to Vṛndāvana and Govardhana in the Raghuvaṁśa of Kālidāsa (late 4th-early 5th century CE) as well as the compositions of the Alzvar saint-poet Āṇḍāḷ from Tamil Nadu who visualizes a pilgrimage to Mathurā, Gokula, Vṛndāvana, and Govardhana. Āṇḍāḷ lived around the 9th century CE.

Early medieval poets like Bilhaṇa and Śri Harṣa also mention Vṛndāvana and what is noteworthy about Bilhaṇa is that he makes a passing reference to Rādhā and Lord Kṛṣṇa sporting in the forests along the Yamunā. This is perhaps one of the earliest references to Rādhā and her association with Kṛṣṇa (early 12th century CE).

Alberuni, the chronicler who accompanied the invader Mehmud Gazni to India makes a reference to Mathurā as being well known on account of Vāsudeva i.e Kṛṣṇa. He mentions Mathurā as the birthplace of Vāsudeva and his growing up in its neighborhood.

When we use terms like ‘tīrtha’ or ‘kṣetra’ they generally imply sacred geography. Sacred geography invariably entails a specific geographical and physical space that serves as the fundamental context in connection to which all aspects of that sacred space develop.

Added to this is the concept of maṇḍala which encompasses a sacred geometry. Whether it is a sacred geography, landscape, or geometry, space is the key element. Further a sacred site as per common belief is a place where the divine chooses to reveal itself (Singh 2013: 88).

This belief underlies all features of a sacred place. Moreover, though divinity is omnipresent, in certain special places its potency is greater than other sites making people visit that particular sacred site. This holds very true for Mathurā. Though there are many kṣetras associated with Lord Kṛṣṇa in India including Dvārakā none is considered as sacred as Mathurā.

The Mahātmya texts on Mathurā tell us that Mathurā is something that only a few chosen devotees of the Lord can attain and every devotee exerts himself or herself to seek entrance into the category of the chosen few.

Connected to the sacred landscape are the belief systems which may be rooted in the religious canons or based on oral folk traditions as well as the ecology. These belief systems engender the consciousness of a site which along with spatial context delineate the sacred landscape. (Singh 2013: 91).

Prof. Rana P.B. Singh has quoted Roger Stump who has given seven categories of sacred spaces (Singh 2013: 97). Mathurā fits into the category of a ‘theocentric’ and ‘historical’ sacred space. A theocentric sacred space is defined as ‘continual presence at a location of the divine or superhuman’(Ibid).

The Mathurā region since the early medieval period is entirely centered around the powerful personality and divinity of Lord Kṛṣṇa who as per the texts discussed by the present author considers Mathurā and Vṛndāvana as his eternal abodes where he dwells continually.

A ‘historic’ sacred space is defined as ‘association with the initiating events or historical development of a religion’(Ibid). Mathurā is thus also a ‘historic’ sacred space as the various Mahātmya texts combined with the archaeological evidence enable us to chart out the historical evolution of Vaiṣṇavism in Mathurā from the Pāñcarātra sect to a multitude of medieval sub-sects revolving around Lord Kṛṣṇa’s aspect as the lovable teenage cowherd boy of Vraja.

The term kṣetra originally meant an agricultural field but in the course of time, it was used more in the context of a sacredscape. A kṣetra is a specific territory of a particular divinity and may encompass a number of sacred sites. It is also invariably associated with a tīrtha which in common terms means a water body.

A tīrtha could be the vast ocean or a small natural or manmade reservoir. A kṣetra in later times was conceived also as a maṇḍala. A mmaṇḍala is essentially a circle with a square and radial symmetries. It is considered the most archetypal manner in which the interior urban space was connected to the external cosmos (Singh 2013: 271).

It is a circular diagram consisting of squares and triangles which after consecration acts protection from negative forces (Swami Harshananda 2008: 287). In polity, we use the term maṇḍala to denote a king’s domain.

The Kṛtyakalpataru

The oldest datable mahātmya highlighting the greatness of Mathurā is found in the eighth part of the Kṛtyakalpataru, a text which falls in the category of a nibandha or digest under the vast a number of Dharmaśāstra texts.

This eighth part is the Tīrthavivecana Kāṇḍa which is perhaps the first significant work outside the perimeter of the Itihāsa-Purāṇa literature which deals systematically with the concept of tīrthas and the practice of tīrtha yātrā. Its compiler, Lakṣmīdhara Bhaṭṭa was the chief minister of Govindacandra, a Gahadavala Rajput ruler, thus placing him in the early part of the 12th century CE.

The Kṛtyakalpataru is a purely nonsectarian text and deals with a wide range of tīrthas starting with Kāśī, Puṣkara, Ujjayinī, Pṛthuḍaka, Prayāga, Dvārakā, Gayā, Kokāmukha, Sukara, and Mathurā. The Mathurā Mahātmya section of the Kṛtyakalapataru mainly draws its contents from the Varāha Purāṇa which is in the form of a dialogue between Varāha and Bhū Devī and only a small part from the Viṣṇu Purāṇa.

Alan Entwistle raises doubts about the authenticity of the verses quoted by Lakṣmīdhara as belonging to the original Varāha Purāṇa and also questions the version of the Mahātmya available in the 20th century CE (Entwistle 1987: 231).

Lakṣmidhara’s version of the Varāha Purāṇa’s Mathurā Mahātmya is a much-abridged form of the extant Varāha Purāṇa’s Mathurā Mahātmya. Some phrases occur in both works. There is a possibility that these verses were composed much before the Kṛtyakalpataru and passed on orally by the Brāhmaṇas of Mathurā who was in a way the custodians of the pilgrimage the tradition of Mathurā.

The version of the Mathurā Mahātmya in the Kṛtyakalapataru and the extant Varāha Purāṇa highlight the incarnation of Viṣṇu as Kṛṣṇa in the Dvāpara Yuga in Mathurā and Varāha, in fact, calls Mathurā ‘janmabhumi priyā mama’ in the first few verses of the Mahātmya.

Mathurā is also called Viṣṇu or Varāha’s greatest ‘Muktikṣetra’ which is well known. Viṣṇu mentions that he will take birth in four mūrtis -Kṛṣṇa, Balarāma, Pradyumna, and Aniruddha in Mathurā. This is a reference to the ancient Vyuha concept of the Pāñcarātra school of Vaiṣṇavism which had its origins in the Mathurā region and was an outcome of the practice of hero-worship of the Vṛṣṇi scions starting with Vāsudeva Kṛṣṇa and followed by his brother Balarāma or Saṃkaraṣaṇa, Kṛṣṇa’s son Pradyumna and grandson Aniruddha.

This Caturvyuha form has been depicted in the Kuṣāṇa-Gupta period art of the Mathurā School. The Pāñcarātra Āgamas give the philosophical interpretation of this Caturvyuha doctrine. Thus this version retains some of the most ancient elements of Vaiṣṇavism which reinstates its early origin. Asi Kuṇḍa is mentioned as the central tīrtha of Mathurā, a position that was later bagged by the Viśrānti Tīrtha or the modern Viśrāma Ghāṭa.

The other places mentioned are Vṛndāvana, Bhāṇḍirakavana, Yamalārjuna Kuṇḍa, Arkasthalam or the Dvādasāditya Mound (in Vṛndāvana), Virasthalam, Kanakam, Somakuṇḍa, Rādhākuṇḍa, Vatsakriḍanam, and Govardhana. Govardhana is mentioned as a place dear to the Bhāgavatas with Indra, Yama, Varuṇa and Kubera tīrthas in its cardinal directions.

There is also a reference to lamps being lit on the summits of the mountain and this reference is also seen in later literature. The importance of the river Yamunā is emphasized and the text states that the Mathurā Maṇḍala or the circular area around Mathurā is twenty yojanās.

In fact, the Mathurā Mahātmya section of the Kṛtakalapataru adapted from the Varāha Purāṇa uses the term ‘Mathurā Maṇḍala’ for the first time making Mathurā and her surroundings a sacred cultural landscape.

In archaeological terms, Mathurā is the epicenter and the maṇḍala is its catchment area. Apart from Mathurā, the other two places that are highlighted are Vṛndāvana and Govardhana though the Kṛtyakalapataru makes no reference of the legends drawn from Lord Kṛṣṇa’s life associated with these sites.

Kāliyahṛda, Bhāṇḍiraka, and Yamalārjuna are the only other places mentioned which share a connection with Lord Kṛṣṇa’s life though the actual incidents are not mentioned with exception of Kāliyahṛda wherein Viṣṇu state that he will kill Kaṁsa in the Dvāpara Yuga. However, the canonical Vaiṣṇava texts clearly state that Kṛṣṇa killed Kaṁsa in Mathurā and not at Kāliyahṛda which is in Vṛndāvana. Rādhākuṇḍa which is one of the most sacred sites for the Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇavas is mentioned in passing but no myths sanctifying the reservoir are given.

The text makes no reference to Rādhā at all or for that the matter even the Gopīs who gain supreme importance in later sectarian texts. According to Entwistle, the mention of Rādhākuṇḍa may be an expression of her popularity or at least present in the oral or folk traditions of Vraja (Entwistle 1987: 230) However by the 12th century CE Rādhā was already a popular figure in western and eastern India if we are to consider Hāla’s Gāthāsaptasai and Jayadeva’s Gitagovinda as testimonies of the growing popularity of Kṛṣṇa’s beloved.

The Mathurā Mahātmya of the Extant Varāha Purāṇa

Of all the descriptions of Mathurā in the Purāṇas, the most detailed and elaborate is the one found in the Varāha Purāṇa. The present author has referred to the Chowkhamba Krishnadas Academy Edition of the Varāha Purāṇa wherein the Mathurā Mahātmya is contained in the adhyāyas 150-178. The initial chapters share some common phrases with Lakṣmīdhara’s version. Mathurā is described as a city which is reputed as the greatest kṣetra of Viṣṇu.

Here the word used is just kṣetra and not mukti kṣetra as in the case of the Kṛtyakalpataru. Mathuṛā is described as a beautiful and expansive city which is the beloved birthplace of Viṣṇu in his incarnation as Kṛṣṇa.

Mathureti Vikhyātamasti Kṣetram Param Mama |

Suramyā ca Susastā ca Janmabhumih Priyā Mama ||11|| (150.11)

The Mahātmya further states that the fruit that one gets during Mahāmāgha at Prayāga and when Rāhu affects Sūrya at Kurukṣetra, one gets the same fruit at Mathurā every day. The merit that one will gain after spending a thousand years in Vārāṇasī is obtained in Mathurā within a moment. This is the potency of Mathurā.

This version, unlike the previous one, compares Mathurā with other equally well-known tīrthas and tries to establish the supremacy of Mathurā over all of them. Further, the text says that when Janārdana sleeps (from Deva Śayanī Ekādaśī to Deva Bodhinī Ekādaśī all the tīrthas congregate in Mathurā Maṇḍala.

Viṣṇu or Varāha also emphatically states that in the Dvāpara Yuga, he will be born in the

family of King Yayati. As is well known, the Kurus and Yadavas (the family to which Lord

Kṛṣṇa belonged) descended from Yayati.

Bhaviṣyāmi Varārohe Dvāpare Yugasansthite |

Yayatibhūpavaṁśe ca Kṣatriyaḥ Kulavardhanaḥ || 24|| (150.24)

There is a further reference to Viṣṇu being born in four images which are similar to the reference in the Kṛtyakalpataru. However here instead of the mūrtis of Vṛṣṇi heroes, the four mūrtis are all of Viṣṇu but in different raw materials like one made of sandalwood, one radiant like gold, one similar to an Aśoka tree and the fourth like an utpala flower.

The reference to these four kinds of Viṣṇu mūrtis sounds out of the context and nothing further s said about them in the text. The replacement of the mūrtis of the Vṛṣṇi heroes perhaps indicates the decrease in the popularity of their worship and the concept of Vyuhas and the entire focus now shifting towards Vāsudeva Kṛṣṇa alone.

As we all know the Yamunā has been the life bestower of the entire Vraja region and it is because of her flow that human habitation could thrive on here since the pre-historic period and expand in the late Iron Age (circa 600 BCE). The Mathurā Mahātmya praises Yamunā as Vaivasvata Manu’s sister (and the daughter of Vivasvān or the Sun) and describes all the tīrthas along her stream.

The first tīrtha to be mentioned is, of course, the Viśrānti Tīrtha which as per the text is famous in all the three worlds. Bathing at this tīrtha enables a person to attain Viṣṇuloka. There is also a mention of the deity at Gataśrama which is near Viśrānti Tīrtha where there is a temple dedicated to Nārāyaṇa. Just glancing at this deity confers the fruit of bathing at all the tīrthas. Gataśrama was an important Vaiṣṇava locality near the Viśrānti Tīrtha since the Kuṣāṇa times. A few relief sculptures depicting episodes from Lord Kṛṣṇa’s life as well as some Kṛṣṇa and Viṣṇu sculptures in the round have been found from this locality.

All these sculptures fall within the time bracket of the 2nd century CE to 10th century CE. Going by these sculptures, we may state that the Gataśrama Nārāyaṇa temple or some Kṛṣṇa or Viṣṇu shrine must have been in existence since a fairly early period at Gataśrama.

Further, the text gives a list of other tīrthas along the Yamunā like Prayāga Tīrtha, Kanakhala Tīrtha, Tinduka Tīrtha, Sūrya Tīrtha, Bodhi Tīrtha, Dhruva Tīrtha, Ṛṣi Tīrtha, Mokṣa Tīrtha and a few others. Sūrya Tīrtha as per the text is the place where King Bali, the grandson of the Daitya ruler and great Vaiṣṇava Prahlāda prayed to the Sun God for the restoration of his wealth after he was sent to the netherworld by Vāmana-Viṣṇu.

We will make a reference to sun worship in Mathurā a little later. The fruit of bathing at all these tīrthas is that one is emancipated from all sins and death at any of these tīrthas takes you directly to Viṣṇuloka which is a place of no-return.

The attainment of Viṣṇuloka after death in Mathurā is stressed repeatedly and this is perhaps an attempt to highlight Mathurā as not only a Vaiṣṇava sacred site but also its equal if not higher ability to confer mokṣa in comparison to Vārāṇasī.

The description of the tīrthas is abruptly interrupted by the description of the twelve vanas in the vicinity of Mathurā as a part of the narrative of King Kṣatradhanu and his queen Pivarī and their pilgrimage to Mathurā. Starting with Madhuvana which is in all probability the ancient site of Mathurā, the text gives a list of the twelve vanas which are- Madhuvanam, Tālavanam, Kundavanam, Kāmyavanam, Bahulavanam, Bhadravanam, Khadiravanam, Mahāvanam, Bilvavanam, Bhāṇḍiravanam, and Vṛndāvanam. Vṛndāvanam which attended unprecedented stature from the mid 16th century CE onward is described as-

Vrndayā Pariraksitam Mama Caiva Priyam Bhume Sarvapātakanaśanam ||48|| (151.48)

However, none of these vanas with the exception of Vṛndāvana have been mentioned in the context of Lord Kṛṣṇa and episodes from his life. In the context of Vṛndāvana, it is said that those who have the darśana of Govinda in Mathurā (Vṛndāvana) are saved from Yamaloka and attain the fortune of Puṇyātmas. Except for Vṛndāvanam and Bhāṇḍirakavanam, none of the other vanas feature in the Kṛtyakalapataru.

After the description of the Vanas, the Mahātmya mentions a few other tīrthas like

Dharapatanaka, Nāgatirtham, Ghanṭābharaṇa, Daśāsvamedha, Vighnarāja, Koṭi, Akrura,

Vatsa Kriḍanakam, Bhaṇḍira, and Keśi Tīrthas. The fruit one gets by bathing and leaving the mortal coil at this tīrthas is also mentioned.

The Daśāsvamedha which is an extremely prominent tīrtha in Vārāṇasī is also there in Mathurā which as per the text was created by Brahmā through his mind. The reason perhaps behind situating this Tīrtha at Mathurā may be to underline Mathurā’s equal status with Vārāṇasī.

This is also what is called spatial transportation where other sacred places are incorporated into the sacred landscape of Mathurā (Singh 2013: 91). As far as the greatness of Akrura Taīrtha is concerned, bathing there during a solar eclipse confers the results of Rājasūya and Aśvamedha yajñas. The fruit of a pilgrimage is often considered greater than that of a yajña. According to the Kṛtyakalpataru-

Tirthābhigamanam Puṇyam Yajñaihi Viśiṣyate

Yajñas was a very costly activity and only a select few people were eligible to perform

them. On the other hand, a pilgrimage or tīrtha yātrā was something any person could

undertake irrespective of his/her socio-economic status, so much so that even Cāṇḍālas could go on a pilgrimage. Further, it was open to all four āśramas.

The general assumption which is even reflected in our text is that the significance of a pilgrimage is that it is equal to the performance of yajña without any social or financial constraints related to the latter. Following the description of the Akrura Tirtha, our text describes the glory of Vṛndāvana which has a beautiful verdant setting and Viṣṇu states that he will play here along with cows and gopālakas.

This is followed by the description Keśi Tīrtha which was the place where Lord Kṛṣṇa killed the horse-demon Keśi and today this tirtha is known as the Keśi Ghāṭa in Vṛndāvana. Our text considers this tīrtha to be far more sacred than Vārāṇasī and the piṇḍadāna here is more merit conferring than at Gayā. If one bathes, donates, and performs home here one procures the fruit of an Agniṣṭoma sacrifice.

Further, the text mentions the famous Dvadaśāditya or Sūrya Tīrtha where Kṛṣṇa killed Kāliya and established the Ādityas. As per the myth mentioned in the text, the Ādityas wanted to bathe in this place and Viṣṇu enabled them to do so.

It is said in our text that the darśana of Āditya at this site is very meritorious and those who pass away here attain Viṣṇuloka. This place is also known as Sūrya Tīrtha. Similarly, according to Dr. Kumar Gupta, this site must have been an important center for sun worship (Gupta 2008: ). There are many images of Sūrya in the Mathurā Museum dating from the Kuṣāṇa period onwards which attest the prevalence of a fairly dominant sun cult.

As per the Kṛṣṇaite legends, this was the dwelling place of Kālīya, the multi-hooded serpent. Dvādaśa Ādityas is a concept going back to the Ṛg Veda where the twelve Ādityas were the sons of Aditī and Viṣṇu was one of them. In the Bhagavad Gītā, Kṛṣṇa describes himself as Viṣṇu among the Ādityas –

Ādityānām Aham Viṣṇuh | (B.G. 10.21)

The Bhāgavata gives a list of twelve Ādityas of which the chief is Viṣṇu. In the Vedic times, Viṣṇu was a solar deity. In Vaiṣṇavism each of the Ādityas is a form of Viṣṇu as the sun god. As per a local myth, Sūrya prayed to Kṛṣṇa at this site. The word ṭīlā indicates that this place is an archaeological mound. It was also the seat of an ancient Bhāgavata shrine dating back to the 3rd century BCE.

This indicates that this site had an early connection to nascent Vaiṣṇavism. Sanātana Gosvāmin, one of six gosvāmins nominated by Caitanya Mahāprabhu to regenerate Vraja chose this mound to get the temple of Madana Mohana constructed in the 16th century CE.

There is also a reference to a Sūrya Tīrtha which in probability is the Dvādaśāditya Mound. By references to the Sūrya Tīrthas in the text, may infer that Mathurā was a very prominent center or the worship of the Sūrya. The text also contains a legend which states that Lord Kṛṣṇa had prayed toSūrya for a son in Mathurā.

Viṣṇu/Varāha/Kṛṣṇa is supposed to have said that because of the grace of Sūrya he was blessed with a handsome son and had the darśana of Padmahastaḥ Divākaraḥ i.e. the Sun God holding lotuses in his hands. Coins of kings whose names ended with ‘Mitra’ which is a synonym for Surya have been found in large numbers in Mathurā.

More conspicuous evidence of the Sun worship is the copious number of Sūrya images that have been found in and around Mathurā from the Kuṣāṇa period onward right up to the medieval period. Almost all images of the Sun God depict him with full-blown lotuses in his hands which matches with the form in which Lord Kṛṣṇa is said to have seen Sūrya.

Sūrya is also depicted seated on his chariot. The popularity of Sun worship in Mathurā may have been partly due to the encouragement given by the Śaka and Kuṣāṇa rulers who also supported/practiced some form of the Iranian religion where sun worship is accorded a lot of significance. Moreover judging by Surya sculptures of the Śunga period at Bhaja (Maharashtra), Bodhgaya (Bihar), and Khandagiri (Odisha) we understand the existence of Sūrya worship in western, northern and eastern India.

Sūrya is also called the Kuleśvara of Māthuras or the people (more specifically Brāhmaṇas) of Mathurā and though the original purport of this word is difficult to understand, it nevertheless highlights the position of the sun god as one of the most prominent tutelary deities of Mathurā and the family deity of at least some families in Mathurā. Śantanu, the ancestor of the Kauravas and Pāṇḍavas is also said to have prayed to Sūrya for a son and the god responded by blessing him with a strong (Mahābalaḥ) sons like Devavrata or Bhīṣma.

The story of Lord Kṛṣṇa cursing his extremely handsome son Sāṃba to be afflicted with leprosy because of his licentious behavior towards women is narrated in the context of many Sūrya sthalas in India. According to our text, the crippled Sāṃba was told by Sage Nārada to pray to the Sun God who could relieve him from his miseries. Accordingly, Sāṃba prayed to Aditya at Mathurā, and the god, in turn, restored him to his former healthy self.

The Bhaviṣya Purāṇa which was narrated by the Sun to Sāṃba was compiled by the latter who as per our text restored the glory of the Sun in Mathurā. Sāṃba is also supposed to have established an image of Sūrya in Mathurā with his own name and thus Sūrya who is the Kuleśvara of the residents of Mathurā as per the Varāha Purāṇa came to be known as Sāṃbapura. Sāṃbapura might be the name of the locality where there may have been a shrine dedicated to Sūrya. Sāṃba’s connection with Mathurā is not accidental.

He was one of the Pañca Vṛṣṇi Viras (Five Vṛṣṇi Heroes) who was worshipped along with his illustrious father, uncle, brother and nephew. The worship of these Vṛṣṇi heroes was extant in the Kuṣāṇa period as indicated by epigraphic evidence. However, he did not find a place in the Caturvyuha concept of the Pañcarātra Vaiṣṇavism.

After a discussion on Mathurā and Sun Worship, let us now see what our text states about the Śaiva elements therein. There is a reference to sites like Virasthala, Kuśasthala and Puṣpasthala and the first one is described as a Śiva Ksetra which is today identified with Bhuteśvara Śiva who is considered the Kṣetrapāla or guardian deity of Mathurā.

As per the text, Siva requested Viṣṇu to grant him a permanent place in Mathurā and Viṣṇu made him the Kṣetrapāla of Mathurā. The Mathurā Parikramā is incomplete without the darśana of Bhuteśvara Mahādeva. In the Mathura State Museum is a relief sculpture dated to the Kuṣāṇa period depicting a group of Śakas worshipping a Śiva Linga which might be the original Śiva Linga f Bhuteśvara. There is also a reference to Gopiśvara Mahādeva in Vṛndavana and the situation of the Sapta Sāmudrika Kūpa near it.

Today no such well can be traced near the Gopiśvara Temple and the actual Sapta Sāmudrika Kūpa is located in the campus of the Mathurā State Museum in Dampier Nagar, Mathurā. The Gopiśvara Mahādeva Temple is an important Saiva shrine in Vṛndāvana. As per a local legend, Śiva was transformed into a gopī (cowherd girl) when he intended to participate in the autumnal dance of Kṛṣṇa in Vṛndāvana.

In Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇavism, Śiva is considered to be a great devotee of Kṛṣṇa. This legend in the opinion of the present author is used to justify the presence of a Śaiva temple in midst of sacred center, essentially Vaiṣṇava or Kṛṣṇaite in orientation. In Vaiṣṇvaism in general and Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇavism, in particular, all deities are considered lower to Kṛṣṇa and their existence is seen only with their forced association with Kṛṣṇa.

The Gopiśvara Mahadeva temple is supposed to have been consecrated by Vajaranābha, the great-grandson of Kṛṣṇa and is considered to be among the important Śaiva shrines in Vraja. Our view is that perhaps the Gopiśvara Mahādeva temple was originally worshipped by the cattle herder population (gopas) of Vraja and as the cult of Kṛṣṇa gained ascendancy in this region, a myth may have been invented to justify the presence of a prominent Śaiva shrine in the midst of a predominantly Kṛṣṇaite religious landscape. (Nagarkar 2018: 5)

A similar process of assimilation takes place in the context of Bhuteśvara, the prime Śaiva shrine in Mathurā. The text clearly states that those who die between the deities of Govinda and Gopiśa, attain the Loka of Indra. Śaivism in the Mathura region was very much in existence since the Kuṣāṇa period. Also in the Gupta period, the Pāśupata sect of Śaivism was very much prevalent in Mathurā as testified by the Mathurā Pillar Inscription dated to the 1st or 5th regnal year of Chandragupta II Vikramāditya.

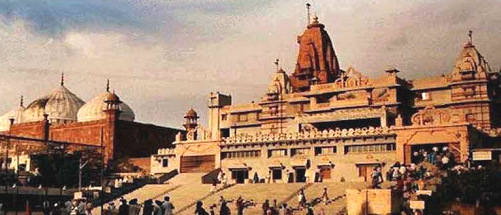

There is also a sculptural panel belonging also to the Gupta period which depicts Lakuliśa, the founder of the Pāśupata Sect discovered in the vicinity of Mathurā. Apart from these, there are numerous sculptures found in and around Mathurā which are Śaiva in affiliation. Then the text speaks about the Keśava Deva temple and today this temple is known as the Śri Kṛṣṇa Janmasthāna at Mathurā.

The existence of a temple dedicated to Vāsudeva-Kṛṣṇa at this site goes back at least to the 1st century BCE. We will discuss more on this when we will consider Śrila Rupa Gosvamin’s Mathurā Mahātmya. As per the text, the one who circumambulates Keśava Deva attains the puṇya of the seven dvipas. In the Purāṇas we have the concept of seven islands of which Jambudvipa is one and Bhāratavarṣa is situated in Jambudvipa.

Further, a person performs Deepadāna i.e. lighting lamps before Keśava Deva, the Lord will take him to his loka in a golden Vimāna. From Adhyāya 157 onward, the Mathurā Mahātmya gives details about the Mathurā Maṇḍala pradakṣiṇā or parikramā. This text formed the basis of the circumambulation of the Mathurā Maṇdala which became a popular practice from the 16th century CE onward.

Glorifying Mathurā, the text states that the Saptaṛṣis were told by Brahmā that the merit one will receive after the circumambulation of Mathurā will be far greater than the merit one will get after the darśana of all gods and tīrthas. The text tells us that the Saptaṛṣis established their ownāśramas in Mathurā. This myth was perhaps inserted to add to the aura of the sacred landscape of Mathurā.

The parikramā commences on the Aṣṭami of the Śukla Pakṣa of the month of Kārtika. Even today, lakhs of pilgrims throng Mathurā during the month of Kārtika and perform the parikramā though the sites covered may vary as per their sectarian affiliations. According to the text, the parikramā undertaken during Kārtika emancipates the pilgrims from all sins.

The parikramā starts with a bath at the Viśrānti Tīrtha which is followed by the darśana of Dīrgha Viṣṇu, Keśava Deva and Svayambhu Deva i.e. Viṣṇu. These temples definitely have hoary antiquity and are certainly older than the Kṛṣṇa temples in Vṛndāvana.

The oldest is, of course, Keśava Deva with a history of at least 2100 years! Following the Vaiṣṇava temples, the text provides us with an exhaustive list of Devis who are definitely local folk goddesses. Some of the goddesses mentioned are Vasumatī, Aparājitā Kāmvasanikā, Augrasenī, Gṛhadevīs, Vāstudevīs, Yoginī, Carcikā, Asprsyā, and Sprsyā.

The last two goddesses are described as Mātṛkāas who would protect children. In Hindusim, especially in the Śākta cult, we have the concept of the Sapta Mātṛkās who are the Śaktis of the principal gods of Paurāṇic Hinduism. Sculptures of Sapta Mātrkās are available since the Kuṣāṇa period in Mathurā. Though none of the goddesses mentioned are included in the general list of the Seven Mothers they are certainly protector goddesses.

Augrasenī could have some connection with Ugrasena, the father of Kaṁsa who was dethroned y his son. The temple of Carcikā Devī commemorates Yogamāyā, the sister of Lord Kṛṣṇa whom Kaṁsa tried to kill. This temple is near the Yogamāyā Ghāṭa. A few of these goddesses also indicate a Tāntric element in Mathurā though it never really flourished in this region.

Most of these goddesses cannot be traced now and today the principal goddess of the region of Mathurā is Rādhā. Visiting the twelve vanas in the Mathurā region is a mandatory part of the parikramā and equally important is visiting these vanas in the prescribed sequence. The pilgrims should start with Madhuvana and conclude the vana yātrā by visiting Vṛndāvana.

The reason for visiting Madhuvana first might be the lingering memory of the vana being the site of the first settlement at Mathurā which is also corroborated by the Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇa and Harivaṁśa. The present text does not get into any myths regarding these forests but Śrila Rūpa Gosvāmin’s version associates each of these forests with some ‘līlā’ or pastime of Lord Kṛṣṇa.

The act of parikramā and the conception of Mathurā as a maṇḍala are interrelated. Adhyāya 161 of the Varāha Purāṇa describes Mathurā Maṇḍala in the form of a lotus and states that Keśava Deva is situated on the karṇikā or pericarp of the lotus. This is obviously due to the preeminence of the Keśava Deva Temple among all shrines in Mathura. As per our text, this temple is surrounded by Devadeva Harideva on the west at Govardhana, to its north is Govinda Deva , to its east is Viśrānti Deva and to its south is the image Varāha.

What the text means by Viśrānti Deva is not clear but all the other deities mentioned are very much in existence. The cult of Varāha in Mathurā was extremely popular and there are two Varāha temples namely the Śveta Varāha and Ādi Varāha not far from the 19th century CE Dvarakādhīṣa temple in Mathurā.

The inclusion of the detailed Mathurā Mahātmya in the Varāha Purāṇa as well as certain myths connecting the Varāha incarnation with Mathurā (like the Kapila Varāha myth)indicate the presence of a reasonably independent cult of Varāha in Mathurā. (Nagarkar 2019)

The site of Govardhana is also described in some detail. The text tells us that there are four tīrthas in the cardinal directions of the site- Indra (East), Yama (South), Varuṇa a (West), and Kubera (North) which are obviously named after the guardians of the particular directions (Dikpālas). Today none of these tīrthas can be identified (Personal Communication Ms. Yaminee Kaushik).

Govardhana itself is called the Svarūpa of Kṛṣṇa and the sites popular here today are the Harideva Temple which was constructed by the Kachwaha Rajput ruler Bharmal, the Mānasa Gaṅgā, Rādhā Kuṇḍa, Śyāma Kuṇḍa, and Kusuma Sarovara. Govardhana is also called by our text as Annakuṭa and today almost all temples in Vraja celebrate the Annakuṭa Utsava in the month of Kārtika as a tribute to Lord Kṛṣṇa and Govardhana Mountain who are one and the same as per the Bhāgavata Purāṇa and the faith of the devotees.

The origin of this legend is rooted in the Govardhanadhāraṇa episode of the Harivaṁśa which states that when Lord Krsna uplifted the mountain he himself looked like one(61.29). The Bhāgavata in the Daśama Skandha states that Lord Kṛṣṇa declared that he himself was the mountain (10.24.35) The site of Govardhana is also associated with Lord Krsna killing Ariṣṭa, the bull demon and in order to atone himself for the act of killing a bull.

The Lord bathed in the kuṇḍa created by Rādhā. This is the only reference to Rādhā in the entire Mathurā Mahātmya of the Varāha Purāṇa. In the centuries to follow, totally divergent myths were created to explain the origin of Rādhā Kuṇḍa.

The text also has numerous legends to explain the greatness of a tirtha in Mathurā but these do not add any value to the growth of athurā as a religion-cultural landscape. Along with describing Mathurā as a kṣetra or maṇḍala, its old stature as one of the major cities of Bhāratavarṣa is never forgotten by our text. Mathurā is compared to Amarāvatī, the heavenly capital of Indra and Mathurā, the city of Lord Kṛṣṇa is no less than Indra’s city.

The Mathurā Maṇḍala, as per our text resembles a cakra because of the presence of Lord Kṛṣṇa. Towards the end, the Mahātmya becomes more sectarian and Kṛṣṇāite in character. There is no kṣetra across the three worlds which can equal Mathurā-

Mathurāyāhā Param Kṣetram Trailokye Na Vidyate |

Tasyām Vasāmyaham Devī Mathurāyām ca Sarvadā || 12|| (167.12)

The entire Mathurā Maṇḍala is called the svarupa of Viṣṇu and finally, all the sacredness that Mathurā possesses is because of the eternal presence of Lord Kṛṣṇa there.

Sarveṣām Devi Tirthānām ca Param Mahat |

Kṛṣṇenam Kriditam Tatra Tad Śuddham hi Pade Pade ||21|| (167.21)

Śrila Rūpa Gosvāmin’s Mathurā Mahātmya

The 15th and 16th centuries CE witnessed the rise of a strong wave of devotional or Bhakti movements that covered almost the whole of India. Some like the Vaiṣṇava movements initiated by the Bengali saint Caitanya Mahāprabhu (1486-1533 CE) was completely centered around the enigmatic figures of Kṛṣṇa and his consort Rādhā and some like those of saints like Kabir aimed at socio-religious reform focusing on one single formless god or divinity.

Caitanya was certainly not the first of the great Vaiṣṇava saints in India but his life and the Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇava Sampradāya founded by him are the most dramatic and impactful. Considered as the incarnation of Kṛṣṇa and Rādhā both, Caitanya swept the medieval Bengali peasantry off their feet by preaching a simple and egalitarian means of worship without elaborate ritualism which took into consideration the psyche of the common people.

His most authoritative hagiography is the Caitanya Caritāmṛta in Bengali which was composed by Kṛṣṇadāsa Kavirāja around 1615 CE. This text also documents Caitanya’s journey to Vraja around 1512 CE. The Vraja visited by Caitanya was a deserted land full of ancient mounds.

The de-urbanization following the Gupta period and the successive Islamic invasions had left Vraja in a state of ruins and Caitanya felt the need to revive the lilā sthalas or sites of pastimes of Rādhā and Lord Kṛṣṇa. For this task he initially chose two of his most competent disciples – Śrila Rupa Gosvāmin and his elder brother Srila Sanātana Gosvāmin who had in their pre-monastic lives served the Sultan of Bengal.

The two brothers did phenomenal work and used their spiritual, intellectual, and administrative acumen to reclaim Vraja. The two of them, specially Rūpa Gosvāmin composed several works which expound the Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇava philosophy. Their spiritual attainments and austere lives attracted many disciples towards them. The Mathurā Mahātmya was compiled by Śrila Rupa Gosvami mainly as a parikramā guideline for the followers of the Gauḍīya Samparadāya.

The main objective underlying this compilation was to identify and popularise the līlā sthalas of Lord Kṛṣṇa and Rādhā and attract pilgrims and patronage for the growth and preservation of these spots. Rupa was instrumental in reconstructing the Govindadeva Temple at the original Yogapiṭha in Vṛndāvana after he miraculously discovered the icon of the deity Govindadeva.

Govindadeva has been mentioned in Mathurā Mahātmya of the Varāha Purāṇa which we have already discussed and the Vṛndāvana Mahātmya of the Padma Purāṇa. He was the presiding deity of Vṛndāvana just as Keśava Deva was of Mathurā and Harideva was of Govardhana. Similarly, Sanātana Gosvāmin had the monumental Madana Mohana Temple constructed on the Dvādasāditya mound after he too discovered the icon of Madana Mohana under a tree on the banks of the Yamunā.

Comparison between the Mathurā Mahātmya of Rūpa Gosvāmin (MM1) and the Mathurā Mahātmya of the Varāha Purana (MM2)

Barbara Holdrege in her book Bhakti and Embodiment has given a detailed comparison of the two Mathurā Mahātmyas under consideration. She makes it clear that both this sthala purāṇas have a common source, namely the Ādi Varāha Purāṇa though they developed independently.

Holdrege further states that MM2 is a random collection of verses which describe the various sacred places in the region of Mathurā in the early 16th century CE before the land attracted the attention of Gauḍīya Vaisṇavas and the Puṣṭi Mārga followers.

The MM1, on the other hand, is more systematic in the presentation of its contents and the themes have been organized in a manner conducive for Gauḍīya perspective of the Mathurā Maṇḍala. In other words, we may state that MM1 is more sectarian than MM2 and had a definite object behind its compilation.

The Mathurā Mahātmya of Śrila Rūpa Gosvāmin shows no knowledge about the Vaiṣṇavism that existed during the Kuṣāṇa period which was more based on the Pāñcarātra and the system of the Caturvyuhas. The Purāṇas from which Rūpa has sourced the passages are all early medieval or medieval when the phenomenon of emotional bhakti had taken root.

Gauḍīya Vaiṣnavism was continuity and expansion of this very paradigm of bhakti. Rūpa, while compiling the Mathurā Mahātmya has diverted in more than one way from the traditional sthala mahātmyas found in the Purāṇas. In the case of MM2, it is the only source of the statements therein. On the other hand, MM1 is a compilation of statements sourced from different Purāṇas like the Ādi Varāha, Varāha, Padma, Skanda, and Bhāgavata Purāṇas.

In the opinion of the author, the central figure that dominates Rupa’s Mathurā Mahātmya is Lord Kṛṣṇa himself. It is because of his association that the entire Mathurā Maṇḍala is sacred. His pastimes with Rādhā have been given special importance, considering her prominent position in Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇavism.

Though Lord Kṛṣṇa never officially ruled Mathurā, he has been addressed as the ‘King of Mathurā’. As far as Rupa is concerned, Mathurā or the entire Vraja Maṇḍala has no existence independent of Lord Kṛṣṇa.

This was in line with the beliefs of the Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇavas for whom Lord Kṛṣṇa is svayam bhagavān. In MM2, Lord Kṛṣṇa occupies a slightly subsidiary position and Rādhā as we have seen is mentioned only once.

Rupa’s Mathurā Mahātmya lists a total number of twenty-five tīrthas with Viśrānti Tīrtha at the center and twelve tīrthas to its either side. The text states that beginning with the Dasāvamedha Tīrtha there are twenty-four tīrthas which culminate at the Mokṣa Tirtha.

Most of the tīrthas mentioned in this text are the same as those mentioned in the older Mahātmya. Further, Rūpa’s text features many ślokas which extol the greatness of the Yamunā River who is an integral part of Lord Kṛṣṇa’s pastimes in Vṛndāvana. This detailed description of the greatness of the Yamunā is not found in the previous text.

The text remarks that Lord Kṛṣṇa played with the cowherd boys and girls as well as the cows in the waters of the Yamunā. The river is actually compared to the Upaniṣadic Brahman and a statement ascribed to the Padma Purāṇa describes Yamunā in the following words-

The flood of eternal, blissful, spiritual nectar which is called Brahman in the Upaniṣads is the Yamunā which has become a flowing river to purify the world. (Mathurā Mahātmya, Śloka 289)

The waters of the Yamunā give a devotee an association with Lord Kṛṣṇa which is much greater than even mokṣa and these waters also eradicate the fear of Yamarāja (Yamunā is considered the sister of Yama). Further, Rūpa’s text also contains Paurāṇic statements which prescribe a number of rituals to be performed on specific days on the Yamunā which will enable to pilgrim to receive Lord Viṣṇu’s grace.

Our text itself gives very few details about every vana and every vana is associated with some pastime of Kṛṣṇa. Of all the vanas, the text has devoted the most number of ślokas for the description Vṛndāvana which is the supreme and eternal abode of Lord Kṛṣṇa for the Gauḍīyas. This is the last and the most prominent of the twelve forests and is situated on the bank of the Yamunā. It is here that Lord Kṛṣṇa enjoys pastimes with the young cowherd girls and plays with the cowherd boys.

As per our text, this is the place where Hari resides and is protected by Vṛndādevī a forest deity and it is here that gods like Brahmā and Śiva serve Hari. Vṛndāvana is described as a large and dense forest and is very dear to Govinda. The Govardhana hill is referred to as a part of Vṛndāvana. Vṛnadāvana is described as a place ideal for cattle and the pastoral community. It is described as the abode of Lord Kṛṣṇa on earth and all the beings that dwell in Vṛndāvana will go to the heavenly abode of Lord Kṛṣṇa.

The Mathurā Mahātmya of Rūpa Gosvāmin contains a statement from the Skanda Purāṇa which describes Vṛndāvana as an expansive and dense forest inhabited by all kinds of birds and animals and the hermitages of sages. This forest is very dear to Govinda and this is the very site where Lord Kṛṣṇa and Lord Balarāma take their cattle for grazing.

Vṛndāvana is blessed, as per our text with the lotus feet of the Son of Devakī who enchants the whole world with his flute and makes the peacocks dance in excitement. This bountiful land of Vṛndāvana has an area of sixteen krośas as per the daśama skandha of the Bhāgavatam.

Rūpa’s text includes a statement from the Bṛhad Gautamīya Tantra where Lord Kṛṣṇa describes Vṛndāvana as his own abode where all living beings including humans and gods attain the abode (ālayam) of Lord Kṛṣṇa after they leave their earthly bodies. It is here that the gopīs are perpetually associated with Lord Kṛṣṇa in his abode i.e. Vṛndāvana.

Another statement describes Vṛnadāvana to have an area of five yojanās. The implication of these measurements will be discussed in the conclusions. Lord Kṛṣṇa is said to never abandon this abode of his-

Na Tyajyāmi Vanam Kvacit (Mathurā Mahātmya, 388)

Statements like Vṛndāvana is beyond the reach of material eyes does not make Vṛndāvana a mythical place or a purely psychological phenomenon. It has both material and transcendental aspects and both these have been dealt with in our text. A very noteworthy statement that the text borrows from the Skanda Purāṇa is where the ‘huge temple of Govinda’ is mentioned.

The earlier Mathurā Mahātmya only mentions deities without any references to their shrines or temples. Perhaps the deity and the shrine are the same entity for the composer of that text. In all probability, there must have been a temple of Govinda at Vṛndāvana which might have been destroyed or collapsed due to reasons unknown to us.

Rūpa may well have modified the statement of the Skanda Purāṇa to bring the Govindadeva Temple built by him to the attention of the readers and encourage pilgrims to visit it.

This abode of Govinda where he is served by Vṛndā and others is Vaikuntha itself. This text makes Vṛndā, the original tree and protector goddess of Vṛndāvana subordinate to Lord Kṛṣṇa by making her his servant. The greatness of Brahma Kuṇḍa in Vṛndāvana is also described and even today this site is visited regularly by pilgrims.

The description of the Keśi Tīrtha is the same as the older Mahātmya but a few details are added as far as the Kālīya Hṛda is concerned like the description of a miraculous tree and the reference to a Kālīya Tīrtha where Lord Kṛṣṇa danced on the hoods of Kālīya as a child. In all probability, the Kālīya Hṛda and Tīrtha are the same sites. The Hṛda attained the sacredness of a tīrtha Lord Kṛṣṇa vanquished the serpent.

The text also gives details about the site of Govardhana and introduces the concept of the Govardhana Parikramā which is a very popular ritual even today. It is called the abode of Viṣṇu, Śiva, Brahmā, and Laksmī. Govardhana is situated to the west of Mathurā at a distance of eight krośas. The text also gives statements from Purāṇas about the rituals related to the parikramā. Govardhana is also described as the best devotee of Lord Kṛṣṇa.

This is a statement from the Bhāgavatam and highlights the undercurrent of bhakti in Rūpa’s text. Another addition is the reference to a Govinda Tīrtha which was created by Indra from the water he used to bathe Lord Krsna. The Rādhā Kuṇḍa that is just mentioned as a place which destroys all sins in the earlier Mahātmya gets a greater potency and sanctity in Rūpa’s text.

The text tells us that it is especially fruitful to light lamps on the day of the Dīpotsava or Deepāvalī at Rādha Kuṇḍa in the month of Kārtika. Taking a bath on the day of the Bahulāṣṭami in the month of Kārtika at Rādhā Kuṇḍa is especially beneficial as one becomes dear to Lord Kṛṣṇa. Form Gauḍīyas, Bahulāṣṭami is the ‘appearance day’ of the Rādhā Kuṇḍa and even today scores of devotees congregate here on Bahulāṣṭami for a dip and offering lamps.

Just as Rādhā is the beloved of Lord Kṛṣṇa, her Kuṇḍa is also extremely dear to him. After a description of a few other tīrthas like Akrura and Sakaṭārohaṇa, the text summarises the sacred sites in and around Mathurā along with an inventory of the principal deities of Mathurā headed by Keśava Deva.

All these deities are located either in Mathurā or Vrndāvana or Govardhana and are all forms of Viṣṇu and the text declares that they are the same as Lord Nārāyaṇa. Rūpa only includes the forms of Viṣṇu or Kṛṣṇa among the main deities of Mathurā whose glories in his own words are limitless.

The Bhakti-ratnākara of Śrila Narahari Cakravarti

Śrila Narahari Cakravarti was born in Bengal towards the last part of the 17th century CE. He served the deities of Lord Govindadevaji and Rādhā in the Govindadeva Temple at Vṛndāvana. He was known for his humility as well as his expertise in cooking and composing devotional poetry. The author right at the start of his work declares that Vṛndāvana nondifferent from Lord Śri Kṛṣṇa.

Rāghava Gosvāmin from Govardhana was requested by Śrila Jīva Gosvāmin, the nephew of Śrila Rūpa Gosvāmin to take Śrinivāsa Ācārya and Narottama Ṭhākura (associates of Caitanya) on a parikramā of Vraja. Rāghava Gosvāmin narrated the history of the region of Vraja. According to his narration, King Vajranābha, the great-grandson of Lord Kṛṣṇa established numerous villages in Vraja and named them after the various līlas of the Lord(3)

He established many vigrahas of his great grandfather and revealed a lot of kuṇḍas or ponds. Today the entire land of Vraja, specially Govardhana is full of kuṇḍas like Rādhā Kuṇḍa, Śyāma Kuṇḍa, and Kusuma Sarovara. Rāghava Paṇḍita led Narottama Dāsa Ṭhākura and Śrinivasa Acarya in their tour of the various sacred spots in Vraja.

The first sacred site that they visited was the Keśava Deva Temple in Mathurā which was built on the place where Lord Śri Kṛṣṇa is believed to have been born. Going by epigraphic evidence, the Keśava Deva Temple might have been definitely one of the oldest shrines in Mathurā dating back at least to the 1st century BCE. Locations of those holy sites were lost in the course of time till they were rediscovered by Śri Kṛṣṇa Caitanya who has been described in the Bhakti-ratnākara as Vrajendra Kumāra himself (3).

In a personal communication to the present author, Sri Srivatsa Gosvamiji who heads the Caitanya Prema Sansthan at Jaisingh Ghera in Vrndavana stated that Śri Caitanya identified these holy spots on the basis of ancient mounds scattered across Mathurā and Vṛndāvana.

Narahari Cakravarti further tells us that Sri Caitanya described the glory of the sacred spots to Śrila Sanātana and Rūpa Gosvāmins. The two Gosvāmins, specially Śrila Rūpa Gosvāmin took the evidence from the scriptures while compiling his own Mathurā Mahatmya though they were well acquainted with the holy sites in the Vraja region.

After collecting the scriptural references, the two savant brothers personally visited these sites and re-established them. We have already briefly alluded to this before. The text states that it is because of these two brothers that people became aware of all the sacred sites in Vraja. They might have even done sessions of Nāma Sankirtana at these sites through which they propagated the worship of Rādhā and Kṛṣṇa which is the core of Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇavism.

The Bhakti- ratnākara clearly states that it was because of the efforts these two brothers that numerous spots in Mathurā which were associated with the līlas of Lord Kṛṣṇa became known to the people (Cakravarti: 3).

Rāghava Paṇḍita described the glory of the Mathurā Mandala to Narottama Ṭhākura and Śrinivāsa Ācārya and what is significant here is that the whole region of Mathurā is referred to as a Mandala which covers 20 yojanās of land. Narahari Cakravarti, like his spiritual ancestor Rūpa Gosvāmin, presents statements from Purānas to re-affirm his own description about the greatness of Mathurā.

His cites quotations from texts like the Śrimad Bhāgavata, Viṣṇu, Ādi Varāha, Padma and Skanda Purāṇas which extol the glory of Mathurā. Bathing at the different tīrthas in Mathurā on the Yamunā River and the mere residence in the Mathurā Maṇḍala leads to a person being freed from all his sins- intentional or accidental.

Cakravarti provides a statement from the Skanda Purāṇa which makes a reference to Mathurā as the eternal abode of Lord Govinda and his gopīs and residence in Mathurā is the only way to eternal happiness (Cakravarti: 4).

The Adi Varāha Purāṇa, as quoted by Cakravarti goes even a step ahead of the Skanda Purāṇa by equating the residence in Mathurā as the final goal of people seeking the Absolute Truth (Ibid: 5). Generally, Kāśī or Vārāṇasī is considered the city dear to Lord Śiva but in the statement from the Viṣṇu Purāṇa quoted by Cakravarti, Mathurā is described as the city of Lord Mahādeva who in turn has been described as a great devotee of Lord Hari. In many Vaiṣṇava sects, Śiva is considered the greatest Vaiṣṇava (Parama- Vaiṣṇava).

The Mathurā region has many shrines of Śiva known by different names like Bhuteśvara, Rangeśvara, and Gokarṇeśvara. Bhuteśvara Mahādeva has considered the guardian of Mathurā and the parikraṃā of the Mathuṛa Mandala commences at Bhuteśvara.

Archaeological and epigraphic evidence indicates that worship of Siva in Mathurā dates back to the Kusama period and the Pāśupata cult of Śaivism was very much in existence in the Gupta period. Kuṣāṇa rulers of Mathurā like Vimā Kadphises and Vāsudeva have the depictions of Śiva on their coins.

Further, quoting from the Ādi Varāha and Padma Purāṇas, the Bhakti-ratnākara highlights that the residence in the Mathurā is conferred on only those fortunate people who are fully devoted to Hari and have received his grace.

Mathurā for Vaiṣṇavas is the giver of all kinds of liberation for everyone. Here we find the correlation of the actual physical site of Mathurā and the rituals to be performed like piṇḍa-dāna as well as philosophical concepts like attaining Brahman and liberation.

The Padma Purāṇa considers the name Mathurā similar to the syllable Om or Praṇava and states that Ma, Thu and rā represent Mahārudra Śiva, Viṣṇum and Brahmā respectively and they reside in Mathurā as deities. We have already discussed the temples of Śiva in Mathurā and there are temples of Viṣṇu in Mathurā like Gatāśrama Nārāyaṇa and Dīrgha Viṣṇu which are mentioned in many texts speaking about the greatness of Mathurā.

As per the Padma Purāṇa, Mathurā is even more sacred than Vaikuṇṭha dhāman of Lord Nārāyaṇa. In Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇavism, Kṛṣṇa is considered a much higher divinity than Viṣṇu, and the same text gives more stature to Rādhā than Viṣṇu. Cakravarti very clearly gives the extent of the Mathurā Maṇḍala which, as per the Bhakti-ratnākara is from Yāyāvara to Saukāri Bateśvara.

The text tells us that Yāyāvara is derived from the name of a group of Brāhmaṇas who have been mentioned in the Mahābhārata and a few Dharmaśāstras. Saukārī Puri, according to the Purāṇas is the place where it is believed that Viṣṇu in his incarnation as Varāha uplifted the earth and the term Saukāri is derived from the Ādi Sukara i.e. Varāha.

Saukari Bateśvara is identified with modern Batasar which is at the southern tip of the Mathurā Maṇḍala. As stated before, the entire region of Mathurā Mandala covers an area of twenty yojanās which is replete with holy places. These holy sites have been classified by the Purāṇas and spots which are associated with the līlās of Lord Kṛṣṇa and Balarāma cover twelve yojanās.

In its initial parts, the Bhakti-ratnākara more or less follows the Mathurā Mahātmya of Śrila Rūpa Gosvāmin which was for the Gauḍīyas the most authoritative work on Mathurā. The twenty-four tirthas mentioned in the Mahātmya are also mentioned in the Bhakti-ratnākara and so is the Viśrānti Tīrtha.

The text tells us that Caitanya bathed at all the tīrthas and his pastimes at all these tīrthas were so transcendental that it was only possible for Ananta Śeṣa to describe them. Where Cakravarti’s work differs from Rūpa’s is the description of the activities of Caitanya at these sacred spots.

Just like Rūpa compiled a separate Mahatmya to establish the link between the sacred sites in Mathurā and Lord Kṛṣṇa, Narahari Cakravarti wrote the Bhakti-ratnākara to link these very sacred sites to Caitanya.

The overall tone of the Bhakti-ratnākara is far for emotional and devotional than Rūpa’s text. The Bhakti-ratnākara makes an attempt to establish the oneness of Lord Kṛṣṇa and Caitanya. The text describes the ‘transcendental’ activities of Caitanya at almost every site which was visited by him.

Cakravarti tells us that whenever and wherever Caitanya or Lord Gaura Candra as he calls him danced in ecstasy a large crowd would gather around him. The people identified Caitanya as Vrajendra-Nandana himself. The text continuously draws parallels between the lives of Lord Kṛṣṇa and Caitanya and even imposes myths on the landscape to establish the single identity of the two.

The Bhakti-ratnākara also describes certain miraculous activities of the associates of Caitanya like Nityānanda. The text attempts to juxtapose the līlās of Lord Kṛṣṇa and Caitanya in Vraja and bring out the similarities between the two to establish their single identity.

The Bhakti-ratnākara clearly states that Rāghava Paṇḍita, Śrinivāsa Ācārya, and Narottama Dāsa Ṭhākura did not follow the parikramā mārga as given in the Ādi Varāha Purāṇa. They visited the twelve forests in the sequence given by the older texts where Rāghava described to the pilgrims the pastimes of Lord Kṛṣṇa and Caitanya.

Most of the descriptions of Lord Kṛṣṇa’s pastimes have been directly taken from Śrila Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmin’s Vraja Vilāsa Stava. As far as Caitanya’s līlās are concerned, the Bhakti-ratnākara tells us that in Bahulavana Lord Gaura Candra was surrounded by cows and the people who came to see him identified him as Lord Kṛṣṇa in the garb of Samnyāsi.

Many other pastimes of Lord Kṛṣṇa have been given with respect to the other vanas but most have no Itihāsa-Purāṇa base. Cakravarti may have included these myths which were popular oral traditions in the Vraja region though it is difficult to say so with certainty. Our text has devoted many paragraphs for the description of Rādhā Kuṇḍa and its discovery by Caitanya.

Rādhā Kuṇḍa and Śyāma Kuṇḍa were in the 16th century CE located in a village called Arita named after the bull demon Ariṣṭa. The Śyāma Kunda, as per our text was created by Lord Kṛṣṇa by summoning all the holy tīrthas after which he bathed there to atone for the sin of killing a bull. Rādhā also dug her own kuṇḍa with the help of her eight friends and the Lord was very happy to see this Kuṇḍa.

The Śyāma and Rādhā Kuṇḍas as per our texts became the spots for the amorous sports of the divine couple. Among the four texts which we have considered for this paper, it is only in the Bhakti-ratnākara that Rādhā Kuṇḍa has been described as the site of Rādhā and Lord Kṛṣṇa’s conjugal pastimes. This is the Mādhurya līlā of the pair which is seminal to Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇavism.

The text gives a very romantic setting to the two ponds which were surrounded by the kuñjas or groves of the eight sakhīs of Rādhā and the eight sakhas of Lord Kṛṣṇa. The text tells us that Caitanya discovered these kuṇḍas in the midst of paddy fields.

They were then cleared and filled with fresh water. It is quite possible that either Caitanya himself or any of the Six Gosvāmins of Vṛndāvana may have initiated some ritual practices at Rādha Kuṇḍa. Rūpa’s text mentions the rituals at the Rādhā Kunda on Bahulāṣṭami and the Bhakti-ratnākara reproduces the same.

Going by the details of our text, by the late 16th century CE a fairly large Vaiṣṇava settlement had

grown around Rādhā Kuṇḍa. These rituals are not mentioned in the Kṛtyakalpataru and Mathurā Mahātmya of the Varāha Purāṇa. Sites in Govardhana like the Kusuma Sarovara are described as spots for the pastimes of Rādhā and Lord Kṛṣṇa.

The Annakuṭa Kṣetra which has been mentioned in the two Mathurā Mahātmyas is mentioned as the village of Aniyora and some purported etymology of the village is given by the author which seems far from logical. Many other kuṇḍas like the Surya Kuṇḍa at Govardhana and a number of villages have been mentioned.

This indicates that the settlement in Vraja was gradually expanding and some pastime of Rādhā and Lord Kṛṣṇa was randomly associated with each of these settlements.

The text mentions the town of Varsāṇā or Vṛṣabhānupura which is supposed to be the place of Rādhā. Many other sites like Dohani Kuṇḍa a, Dadhi Manthana, and Dhulauda Grāma which have definite pastoral connotations are also mentioned.

The pastoral setting of the līlās of Lord Kṛṣṇa which has mentioned in the Harivaṁśa and the Bhāgavatam is more conspicuous in Rūpa’s text and the Bhakti-ratnākara which emphasize his aspect as Gopāla Kṛṣṇa and do not give any attention to his life in Dvārakā and his role as the mentor and guide of his Pāṇḍava cousins.

Sites like Rādhā’s kitchen and sites like Kokilavana and Anjanaka Grāma are given. Cakravarti gives the etymology of almost every settlement and this etymology is not only based on some līlā (very often concocted) of the couple and linguistically it is derived from the local dialect and not Sanskrit. Many trees with an aura of divinity like the Akṣaya Vaṭa and Bhanḍira Vaṭa where Balarāma killed Pralambāsura are also mentioned.

A mention has to be made of the village called Varāhara were, as per Cakravarti Lord Kṛṣṇa assumed the form of Varāha and played with his friends. This is significant to the reference we have made to the cult of Varāha in the Vraja region and there are a few sites associated with the boar incarnation in and around Mathurā.

Sites like Mahāvana, Gopiśvara Mahādeva, and Akrura Grāma which have been mentioned by the earlier texts are referred. Akrura Tīrtha of the older texts now becomes Akrura Grama signifying the growth of a settlement there. Cakravarti almost follows Rūpa in the description of Govindadeva but now also mentions other temples in around Govindadeva which are in all probability dedicated to local goddesses like Siddheśvarī and Bāginī.

Deities like Madana Gopāla and Gopinātha which were not mentioned by the other texts are also mentioned in this text. Madana Gopāla is the same as Sanātana Gosvāmin’s Madana Mohana and Gopinātha is identified with the temple of Rādhā Gopinātha in Vṛndāvana near the Yamunā.

Following the earlier texts, our text also makes a reference to Kālīya Hṛda and Dvādasāditya Tīrtha. According to the Bhakti-ratnākara, Kālīya Hṛda and Kālīya Tirtha are the same and the present author has already stated so. The text mentions the Kadamba tree from where Lord Kṛṣṇa jumped into the Yamunā to fight with Kālīya.

Even today local guides point out to a Kadamba tree at this site and state that this is the original tree. The focus of the older texts were the sites of Mathurā, Vṛndāvana, and Govardhana but the Bhakti-ratanākara describes a much greater number of sacred sites than any of the previous texts. The settlements in Vraja had definitely grown as it regained its stature as a place of pilgrimage and cultural activity.

The earlier texts mainly describe the tīrthas, vanas, and a few deities with no reference to any actual human settlement. On the other hand, the Bhakti-ratnākara devotes many of its pages to at least name actual villages and their connection with Lord Kṛṣṇa and more so with Rādhā.

Cakravarti may have taken into account the vast body of local legends that may have been floating in Vraja. While the older texts adhered strictly to the Paurāṇic traditions, the Bhakti ratnākara seems to blend both the mainstream and subaltern elements.

Observations and Conclusions

1. The Vālmiki Rāmāyaṇa to some and the Harivaṁśa which is a khila of the Mahābhārata to a great extent gives a vivid description of the city of Mathurā which was the only urban center in the entire Vraja region. If we go by the evidence of the Vālmiki Rāmāyaṇa, the foundation of the urban center of Mathurā can be ascribed to Śatrughna, the younger brother of Rāma who killed Lavaṇāsura who in all probability was a tribal chieftain of Mathurā. Mathurā started out as a capital of Śatrughna and later developed into a commercial and religious center.

The Mathurā of the Harivaṁśa is in tune with the Kuṣāṇa period city of Mathurā when the urbanization of Mathurā reached unprecedented heights. According to Buddhist and Jaina texts, Mathurā was the capital of the Śurasena Mahājanapada but during the lifetime of the Buddha, it was more of a rural settlement. The literary and archaeological sources testify to the fact that till the fall of the Kuṣāṇas, Mathurā was a seat of power of the Indo-Greeks, Śaka-Kṣatrapas, a few local rulers whose names ended with ‘datta’ or ‘mitra’, the Kuṣāṇas and the Nāga rulers.

The last Nāga ruler Gaṇapatināga was defeated by Samudragupta around the middle of the 4th century CE. Mathurā also emerged as a major economic and religious center in the Kuṣāṇa period. In the Kuṣāṇa and Gupta periods, it must have been a city covered with Hindu shrines, temples as well as Buddhist and Jaina stupas and monasteries. The majority of the sculptures and remains discovered in Mathurā since the last two centuries fall under the category of religious artifacts.

Most of the pre and Kuṣāṇa-Gupta period inscriptions record some kind of religious activity. This indicates that even two thousand years back Mathurā was a very prominent religious center or kṣetra for Hindus, Buddhists, and Jainas. Starting off as a political capital, Mathurā evolved into one of the most prominent religious centers of Ancient India in the Kuṣāṇa period.

2. Many foreign authors working on the Vraja region like Charlotte Vaudeville and Maura Corrcoran have considered Vraja to be a ‘mythic’ entity-something that only exists in the imagination of the authors of the Itihāsas and Puranas. Though there are minor discrepancies about the location of certain sites, most of the textual descriptions match with the actual locations of the site. E.g. The texts state that Govardhana is located to the west of Mathurā and it really is. The discrepancies in the distances can arise out of the shift in the locations of the settlements over the period of time.

The earliest habitation at Mathurā was at the Ambariṣa Mound in the northern part of the modern city whereas in the Kuṣāṇa period the city greatly expanded with an increase in the number of settlements. The Purāṇas and Bhakti- ratnākara describe Mathuṛā as a crescent-shaped settlement and excavations have revealed that the city of Mathurā as excavated near the area called Dhulkoṭ was indeed crescent-shaped (Singh 2005: 41). Even Vṛndāvana has yielded Mauryan period bricks and Buddhist remains to belong to the Kuṣāṇa period. Even if we discard literary references as figments of imagination, the archaeological finds give a definite spatial and temporal context to the sites and artifacts.

The Ambariṣa Mound settlement was a simple habitation site that yielded the pottery known as Painted Grey Ware dated to 600-400 BCE. This pottery has been discovered at almost all prominent sites mentioned in the Mahābhārata like Hastināpura and Indraprastha. Though rural in nature, these settlements which are dated around 1000-600 BCE might be coeval to the earliest layers of the Mahābhārata.

3. The Kṛtyakalpataru refers to Mathurā as a kṣetra and a maṇḍala and the word maṇḍala is used by the other three texts also under consideration. However, none of these texts give any philosophical or cosmological interpretation or explanation of the term Mathurā Maṇḍala. Alan Entwistle simply considers the term Maṇḍala to be the circular area around Mathurā.

Today the modern city of Mathurā is at the center of the Mathurā District. The term Mathurā Maṇḍala is used by the texts more as the holy realm of Kṛṣṇa where he is supposed to have physically moved around and performed his divine pastimes. The term maṇḍala has been used mainly to demarcate the sacredscape of Mathurā and its immediate surroundings and to distinguish them from the rest of the profane landscape.

It indicates the dhāman or territory of Lord Kṛṣṇa which is imbued as per the Mahātmya texts and the faith of the devotees is imbued with transcendental qualities. In the opinion of the present author if we are to interpret the term ‘Maṇḍala’ archaeologically it could refer to the catchment area of the site of Mathura.

The site catchment analysis is an important dimension of processual archaeology where the past remains are studies to understand the life processes of the people. There is a central site which in our case is the city of Mathurā and it is has a site catchment or site exploitation territory from which it procures raw materials and resources required for sustenance.

In the entire land of Vraja, Mathurā was the only urban center till the 16th century CE and settlements like Vṛndāvana, Govardhana and Mahāvana or Gokula were its satellite settlements which supplied resources to the city of Mathurā. Being the sole urban center, Mathurā depended on sites like Gokula, Vṛndāvana, and Govardhana for its needs especially pertaining to food, dairy products, and forest resources.

The people who were a part of these networks were the pastoral communities who led semi-nomadic lives. This is clearly indicated in the Harivaṁśa. Urban centers are generally non-food producing centers and depend on their satellite settlements for the food supply. Mathurā was not just the only urban center of Vraja but also the economic, political, and cultural nucleus. The Mathurā Maṇḍala is, therefore, the whole site catchment area with the city of Mathurā as the geographical and national center.

The Mathurā Maṇḍala can be also interpreted as a faithscape which comprises of the sacred space, sacred time, sacred meanings, and sacred rituals. All these elements get their sacredness essentially because of strong faith in the divinity around which the entire sacred landscape is built. People visit a particular place because they have an inherent faith in its elevating and alleviating qualities and texts like the Sthala Mahātmyas help in reaffirming this faith.

The rituals one follows within the defined geographical space at a particular time for a specific result (phalaśruti) deepen and consolidate this faith. The Maṇḍala is an expression of this very faithscape which forms the basis of any sacredscape. This faithscape is superimposed on the actual physical site and it manifests itself through the shrines, temples, tīrthas, and rituals. The parikramā of Mathurā is the most noteworthy expression of this faithscape.

4. The Parikramā as defined in the Mathurā Mahatmya of the Varāha Purāṇa gave a certain well-defined pattern and structure to the pilgrimage of Mathurā. The idea of Mathurā Maṇḍala and the parikramā are in fact intertwined. In fact except for the Kṛtyakalpataru, the other three texts are based on the idea of the parikramā.

The parikramā in the later years varied as per the particular Vaiṣṇava sub sect and the sprouting of new sacred sites.This is clearly reflected in the Bhakti-ratnākara. Many more new sites were added were added to the parikramā circuit and many old sites became obsolete and disappeared from the route of the parikramā. E.g. The Asi Kuṇḍa is the main tīrtha in the Kṛtyakalpataru but in the Mathurā Mahatmya of the Varāha Purāṇa its place is taken by the Viśrānti Tīrtha.

Similarly in the Bhakti-ratnākara the Rādhā Kuṇḍa becomes the most sacred spot to take a ritual bath. Also, minor parikramās like the Govardhana Parikramā were added and soon became very popular. Every Vaiṣṇava sub-sect has its own route of the parikramā. Apart from the old temples of Mathurā which are mentioned in the Mahātmya texts many new sacred sites like Nidhi Vana

and Sevā Kuñja which had sectarian affinities sprang up and new myths were spun to popularise these sites. Many more texts in like Caurāsi Vaiṣṇavan Ki Vārtā and Bhaktamāl also contributed in the increase of sacred sites on the parikramā route.

The most auspicious time for the parikramā was and is the month of Kārtika. The month of Kārtika marks the harvest season and most of the pilgrims visiting Vraja belong to the agrarian communities. After the harvest was reaped and before the new round of crop seeds was sown, the pilgrim- peasants could visit Vraja and earn the fruit of the parikramā. The parikramā is also a leveling process and none of the texts under consideration prohibit any class of people from

performing the same.

5. The four texts under consideration also reflect the growing influence of bhakti or the

devotional element on the sacred landscape of Mathurā. The original religious tradition of Mathurā was also based on the Ekāntika bhakti to Vāsudeva Kṛṣṇa and from the 16th century CE onward bhakti regained her former position. The Kṛtyakalpataru and the Mathurā Mahātmya of the Varāha Purāṇa do not suggest any noteworthy element of bhakti.

The second text is, in fact, replete with ritualism and myths which validate this ritualism. However Śrila Rūpa Gosvāmin’s Mathurā Mahātmya and the Bhakti- ratnākara is founded on the principle of bhakti. The entire sacred landscape of Mathurā is the expression of Kṛṣṇa Preman and Kṛṣṇa Bhakti- the two pillars of Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇavism.

Radha and Caitanya are the best embodiments of these two sentiments. The Bhakti-ratnākara being true to its name visualizes the whole of Vraja as the most sacred expression of bhakti to Rādhā and Lord Kṛṣṇa. Similarly, there is no reference to Rādhā in the Kṛtyakalpataru; in the Mathurā Mahātmya of the Varāha Purāṇa she is mentioned only once whereas in Rūpa’s text she is mentioned in a number of verses but in the Bhakti-ratnākara she even outshines Lord Kṛṣṇa.

The evolution of the description of the Rādhā Kuṇḍa given in the four texts is the best

example to indicate the alteration or expansion of the myth surrounding a pond to accommodate and glorify the character of Rādhā. In Gauḍīya Vaisnavism at times Rādhā even supersedes Lord Kṛṣṇa.

6. The city of Mathurā, especially in Rupa’s Mathurā Mahātmya is often compared to the city of Vārāṇasī and the text emphatically describes how Mathurā is far superior to Vārāṇasī. Even in the Mathurā Mahātmya belonging to the Varāha Purāṇa, Mathurā is considered a far more sacred city than Vārāṇasī.

Generally, Vārāṇasī is considered the place where one gets mokṣa but our Mahātmya texts tell us that leaving one’s body at Mathurā not only gives you emancipation from the cycle of birth and death but also delivers you straight to Viṣṇu Loka which even higher than moksa. Varanasi is a city which belongs to Lord Śiva and Mathurā is, of course, the dhaman or abode of Lord Kṛṣṇa-Viṣṇu. The authors of the Mahātmya texts may have tried to counterbalance the prominence given to Vārāṇasī by projecting Mathurā as an equal or a far greater sacred center. Though we cannot call Vārāṇasi a purely Śaiva kṣetra, Mathurā and its surroundings from the 16th century CE onward grew as a sacred center exclusively for Vaiṣṇavism. Śaivism and Śaktism were assimilated into the fold of Vaiṣṇavism and Buddhism and Jainism had almost disappeared from Mathurā by the medieval period.

7. The chronological sequence of the texts indicates the systematic development of the Kṛṣṇaite cult. In the Kṛtyakalpataru which was compiled around the 12th century CE, Lord Kṛṣṇa is not the central figure and every site in the Mathurā Maṇḍala is not perceived in relation to him. In the Mathurā Mahātmya of the Varāha Purāṇa which might have been written around the end of the 15th century CE or a little earlier, the Vaiṣṇava element becomes even more conspicuous through the entire sacredscape is not filled with Krsnaite affiliations.

Many myths like that of the Kapila Varāha are included in this text which has absolutely no connection with Lord Kṛṣṇa. This myth, in fact, highlights the existence of a cult of Varāha, the boar incarnation of Viṣṇu in the Mathurā region. However, this text, like the Mahābhārata and Harivaṁśa declares through numerous statements that Varāha and Kṛṣṇa are the same.

The Mathurā Mahātmya of Rūpa Gosvāmin and the Bhakti-ratnākara are clearly Kṛṣṇaite in their affiliation. Rūpa’s text does not include any of the myths given in the previous Mahātmya as they make no value addition of the cult of Lord Kṛṣṇa. Rūpa’s text might have been compiled around the 1520s or 1530s when the Mughal rule had just about been inaugurated in the Delhi-Agra region. Similarly, the figure of Rādhā takes center stage in the Bhakti-ratnākara and the entire sacredscape becomes filled with spots associated with some līlā of the couple.

The nature of the līlā may be amorous or otherwise but every site is equally sacred as it experienced the presence of the godly pair. However, one feature that is shared by all the texts is that they all project Mathurā Maṇḍala as a sacredscape associated with Kṛṣṇa-Viṣṇu with not even a single reference to its character as a multi-religious site.

Bibliography

- A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada (trans.), Srimad Bhagavatam, Tenth Canto, PartTwo, Bhakti Vedanta Book Trust, Bombay, 1980. (Reprint 2017)

- A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada (trans.), The Caitanya Caritamrta, Madhya Leela,Volume 7, Bhakti Vedanta Book Trust, Bombay, 1975.

- Jayadayal Goyandka (trans.), Padma Purana, Gita Press, Gorakhpur, Vikram Samvat 2074(2018).

- Jina Prabha Suri, Bhanwarlal Nahta (trans.), Vividha Tirtha Kalpa, 1978. (PDF version)

- Laksmidhara Bhatta, (K.V. Rangaswami Aiyangar ed.), Krtyakalpataru, Volume VIII, Oriental Institute, Baroda, 1942.

- Munilal Gupta (trans.), The Vishnu Purana, Gita Press, Gorakhpur, Vikram Samvat 2072 (2016).

- Narahari Cakravarti, (Kusakratha Dasa trans.), Bhakti-Ratnakara, Ras Bihari Lal & Sons, Vrindavana. (Date of publication not mentioned)

- P.K. Thavre and Desai V.G. (trans), Srimad Bhagavata Puranam, Volume II, Gita Press,Gorakhpur.

- P.L. Vaidya (ed.), The Harivamsa, Volume I, Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Poona,1969.

- Rupa Gosvamin (Bhanu Swami trans.), Bhakti Rasamrita Sindhu, Volumes I and II, Sri Vaikunta Enterprises, Chennai, 2006.

- Rupa Gosvamin, Sri Mathura Mahatmya, Rasikbihari Lal and Sons, Vrindavana.

- Rupa Gosvamin (Bhanu Swami trans.), Ujjvala Nilamani, Sri Vaikunta Enterprises, Chennai,2014.

- Shri Varaha Purana, Gita Press, Gorakhpur, Vikram Samvat 2070 (2014).

- Surkant Jha (ed.), Varahapuranam, Chowkhama Krishnadas Academy, Varanasi, 2014.

- Surya Prasad Dikshit and Mahesh Narayan Sharma (eds), Braj Sanskruti Vishvakosha,Volume I, Parts I and II, Vrindavana Research Institute, Vrindavan, 2015.