Among other cultural markers, the ethos of a civilization is encapsulated in its storytelling and narrative traditions which uncover the heart, the ātmā of that particular civilization. The Indic Civilization can certainly pride itself for having a hoary and rich tradition of storytelling and generating narratives. The ākhyānas incorporated into the Vedic corpus, the Itihāsas, Saṅgama Literature, Purāṇas, Kāvyas, Nāṭakas, Jātakas, Ākhyāyikās, Bṛhatkathā, Pañcatantra, Hitopadeśa, Kathāsaritsāgara and the like exude the inexhaustible wealth of storytelling traditions that developed through the last few millennia in India. The above stated examples are simply the representatives of this tradition which in fact transcends the domains of these classical texts to accommodate folk as well as tribal storytelling traditions. The rich and variegated repertoire of Indic storytelling genres mirrors the political, economic, social, religious, psychological, ecological and cultural facets and worldviews of the numerous communities thriving in the land of India. The same narrative or story may branch out into diverse versions which confirm to the cultural, intellectual and spiritual processes which govern the ways of thinking of a specific segment of the populace.

The land of Vraja is haloed by the birth and transcendental līlās of Kṛṣṇa who was born in the city of Mathurā and brought up in the cowherd settlements of Mahāvana- Gokula and Vṛndāvana. This land of Vraja roughly corresponds to the modern district of Mathurā in the state of Uttar Pradesh. Made verdant by the swift flowing Yamunā River, the land of Vraja has been home to numerous pastoral communities and their innumerable herds of cattle since times immemorial. Vraja features in classical as well as folk narratives as the landscape where Kṛṣṇa was born and performed numerous pastimes in the company of the young gopas and gopīs and in the process ensured liberation to each and every one of them. The region of Vraja developed as a sacredscape since the Mauryan times and it evolved as the main centre of Kṛṣṇa Bhakti since the 16th century CE. This sacredscape was characterized by grand temples, spartan shrines, forests, natural groves, kuñjas and water reservoirs or kuṇdas. Of these, the focus of this paper is on the kuṇḍas in the region of Vraja and the stories of Kṛṣṇa invariably associated with them. Narratives and folklore about water sources are a universal phenomenon. They help in retaining the collective cultural memory of a civilization as water sources, like other natural elements and some manmade features, last for several generations. We come across such water centric narratives in the Mahābhārata and Skanda Purāṇa as well. The step wells of Gujarat have their own concomitant narratives. Water being an indispensable element that sustains and nurtures all life forms, the growth of narratives revolving around water bodies was inevitable. Almost all cultures of the world have generated narratives concerning water which reflect their own perspectives and outlooks with respect to water. Such narratives and folklore associated with water sources evolved in the Vraja region as well. One of the noteworthy hallmarks of these narratives connected to the kuṇḍas is that Rādhā, the epitome of bhakti and Kṛṣṇa ̍s eternal consort in his Vṛndāvana līlās features prominently in them. Other associates of Śrī Kṛṣṇa like his brother Saṃkarṣaṇa- Balarāma, cousin Uddhava, Nanda, Yaśodā as well as the cowherd boys and girls find a place in these narratives. Some of these narratives have their origins in classical textual traditions like the Bhāgavata Purāṇa and the Garga Saṃhitā though many of the other narratives can be attributed to the oral folk stories which have been circulating in the land of Vraja since a number of centuries. These stories highlight the sacred nature of these kuṇḍas and underline the benefit a devotee would receive after purificatory baths in them. These stories serve as a conjunction between the water symbolism and the līlās of Kṛṣṇa. These Kṛṣṇa Kathās associated with the kuṇdas are narrated by spiritual leaders and ascetics to the pilgrims who undertake the Vraja Maṇḍala Parikramā, especially in the month of Kārtika. The stories revolving around the kuṇḍas of Vraja are mainly sourced from oral traditions. They were meant to be narrated to the pilgrims who would visit these kuṇḍas during the course of their Vraja Yātrā. The region of Vraja abounds in the number of kuṇḍas and sarovaras, some of which are natural while some others are entirely manmade. These water bodies, along with the Yamunā River constitute the waterscape of Vraja. Over time, these water bodies came to be associated with one or more life events of Kṛṣṇa. As water bodies, they already possessed a kind of sacredness but their conjunction with the Kṛṣṇa Kathā made them even more pure. K. Ayyappa Paniker has categorized narrative literature into ten different kinds and the stories relating to the kuṇḍas of Vraja could broadly fit into the Purāṇa Model, the Multiple Model (consisting of tribal or folk narratives) and the Mixed Model (Ramankutty, 2010: 69).

Nārāyaṇa Bhaṭṭa ̍s Vraja Bhakti Vilāsa, at different points, provides an exhaustive inventory of a number of kuṇḍas and the deities consecrated near them. A noteworthy concentration of kuṇḍas is found in the Kāmya Vana and at Govardhana. As per the Viṣṇu Purāṇa quoted by Nārāyaṇa Bhatta, the Kāmya Vana alone had a staggering number of kuṇḍas- eighty four in total. The text, in most cases just furnishes a one line narrative about a specific kuṇḍa and then moves ahead to focus on the merit one would incur after a bath in the kuṇḍa. The Vraja Bhakti Vilāsa has also incorporated a number of mantras addressed to the kuṇḍas which enumerate the glories of these kuṇḍas. E.g.

The mantra addressed to the Deha Kuṇḍa states:

Trailokyaśramanāśāya Sarvadānanandadāyine |

Sarvakalmaṣanirdhauta Divyakāyapradāyaka ||

The meaning goes that O, Deha Kuṇḍa, the destroyer of the exertion of the three world, the one who bestows all the happiness, the one who destroys all vices, the one who endows the devotees with a divine body, one offers namaskaras to the Deha Kuṇḍa (Vraja Bhakti Vilāsa, 4.48)

The Bhakti Ratnākara, a Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇava text composed by Narahari Cakravati also supplies fleeting details about the kuṇḍas in the Vraja region. The two veteran followers of Caitanya Mahāprabhu- Śrīnivāsa and Narottama Ṭhākura undertook a pilgrimage of Vraja with Rāghava Paṇḍita as their guide. During the pilgrimage, the two devout Vaiṣṇavas came across a number of kuṇḍas and Rāghava Paṇḍita gladly elucidated to them the glories of these kuṇḍas.

The Vraja Vastu Varṇana, a descriptive text about the sacred geography of Vraja written by Jagatānanda mentions the number of kuṇḍas in Vraja as more than one hundred and fifty nine. He says:

Unsaṭh upar ek sou sigare Braj me kuṇḍa

Aur hi kuṇḍa anek hain te sab nūtana jān

Kuṇḍa purātana ek sou unsaṭh jān (Vraja Vastu Varṇana, Verses 51, 68)

Let us now review some of the narratives related to the kuṇḍas of Vraja.

The narratives connected to the kuṇḍas can be broadly classified into three categories:

- Narratives of Kṛṣṇa centering around his childhood

Varkhoḍā Kuṇḍa

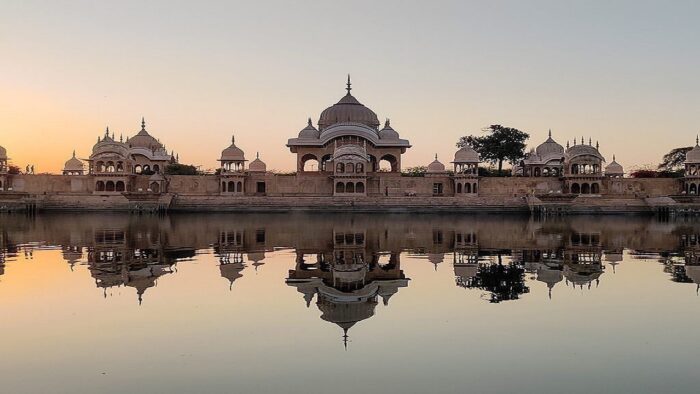

(Figure 1: Krishna Slays Bakasura, the Crane Demon at Varkhoḍā Kuṇḍa – Pic Credit: metmuseum.org)

Varkhoḍā Kuṇḍa is the supposed place where Kṛṣṇa killed the demon called Bakāsura who had assumed the form of gigantic crane. This kuṇḍa is located in the village of Khāyarā. This story is recorded in the 11th Adhyāya of the Daśama Skandha of the Bhāgavata Purāṇa. This kuṇḍa is also known as Bakra Kuṇḍa and Baktharā. The story goes that one day the gopa children took their calves for drinking water to this reservoir. Here they noticed a colossal crane and obviously the gopa children were petrified at the sight of the bird. The bird looked like a huge fragment of a mountain which had been cut by Indra ̍s thunderbolt. The crane demon suddenly gulped down Kṛṣṇa and seeing this, the gopa children including Balarāma fell down unconscious. Kṛṣṇa became heated like a fire and unable to bear the heat, Bakāsura pushed Kṛṣṇa out of his mouth and began piercing him with his long beak. Kṛṣṇa, completely unharmed by this attack caught Bakāsura by both his hands and killed him. Seeing Kṛṣṇa safe and the bird-demon killed, the gopa children and the devas in heaven rejoiced.

Yaśodā Kuṇḍa

(Figure 2: Statues of Hau-Bilau can still be seen at Yaśodā Kuṇḍa)

The Yaśodā Kuṇḍa is the site of a childhood pastime of Kṛṣṇa which traces its origin in the folk culture of Vraja. As per the narrative, Kṛṣṇa and Balarāma would play with their friends on the banks of this kuṇḍa. They would be so engrossed in their play that they would not remember to have lunch. Yaśodā would make all kinds of expressions and actions to get the brothers to have their meal. She would try to scare the two with the stories of two mythical terrifying characters called Hāu and Bilāu. This particular story is a clear example of the merging of a folk tradition of Vraja into the Kṛṣṇa Kathā. Here the divinity of both Kṛṣṇa and Balarāma as Avatāra Puruṣas fades into the background and here they assume roles of children with their own love for play and their own little fears.

Āseśvara Kuṇḍa

(Figure 3: Āseśvara Kuṇḍa)

Āseśvara Mahādeva and Āseśvara Kuṇḍa are both located in Nandagaon. These two are actually associated with a līlā of Kṛṣṇa in Gokula but the local tradition of Nandagaon places this līlā at Nandgaon. The story goes that Śiva, a great devotee of Kṛṣṇa wanted to have a darśana of his lord who had taken the form of an infant. He arrived at the home of Nanda and Yaśodā in the guise of an ascetic but Yaśodā did not allow Śiva to meet Kṛṣṇa as she thought that her baby son would get terrified at the sight of the ascetic. Kṛṣṇa was aware of Śiva ̍s arrival and began to cry as he too wanted to meet Śiva. Śiva is said to have sat near this kuṇḍa with the hope or āśā of catching a glimpse of his lord. Eventually Yaśodā summoned the ascetic and as the devotee and the lord met, the crying of the baby ceased. This story illustrates the integration of Śiva into the Kṛṣṇa Kathā as well as the Kṛṣṇaite landscape of Vraja.

Mānasī Gaṅgā

(Figure 4: One who bathes Manasi-ganga is not only purified of sins, but will also achieves prema-bhakti – the ultimate form of pure devotion to Krishna)

The Mānasī Gaṅgā is a huge water reservoir right in the heart of the town of Govardhana. The legend centering around this water body is that once Nanda intended to have a bath in the river Gaṅgā but Kṛṣṇa was not inclined to send any of the Vrajavāsīs out of Vraja. Accordingly, on the day of Kārtika Amāvasya, Kṛṣṇa brought forth a channel of the Gaṅgā from his mānasa or mind. It is for this reason that this water body is known as Mānasī Gaṅgā and is considered supremely sacred as it issued forth from Kṛṣṇa himself. According to the narrative included in the Vraja Bhakti Vilāsa, Kṛṣṇa brought forth the Mānasī Gaṅgā from his mind because of the speech of the gopīs. As per the Garga Saṃhitā, the Mānasi Gaṅgā forms the two eyes of Girirāja Govardhana. This is a reservoir where Kṛṣṇa and Rādhā are said to indulge in ̍Naukā Vihāra ̍ or a boat ride. As per a belief among the Gaudīya Vaiṣṇavas, Śrīla Raghunātha Dāsa Gosvāmī (one of the six Gosvāmins of Vṛndāvana) had actually witnessed this pastime here. A visit to the Mānasi Gaṅga is an essential part of the Parikramā of Govardhana.

- Narratives of Kṛṣṇa with Rādhā and the Gopīs

The Mānasarovara

(Figure: 5: Manasarovara Kunda)

The Mānasarovara is a picturesque water body located near Vṛndāvana. The narrative associated with this kuṇḍa is based on the romantic play of Rādhā and Kṛṣṇa. We are told that one day seeing Kṛṣṇa enjoy the Rāsa dance with the gopīs, Rādhā was overcome with the emotion of ̍ Māna ̍ and went away to a secluded forest. Rādhā was very livid with Kṛṣṇa as she resented his interaction with the other cowherd girls. Rādhā could not bear the pangs of separation from Kṛṣṇa and began to shed tears. The Mānasarovara is supposed to have been created by the tears of Rādhā at this spot. Kṛṣṇa too suffered by being away from Rādhā and looking for her he arrived at the place where Rādhā sat crying. Kṛṣṇa asked for her mercy and surrendered his flute at her feet.

Brahma Kuṇḍa

(Figure 6: Brahma Kunda)

The Brahma Kuṇḍa, now a highly renovated monument is situated within the temple town of Vṛndāvana near the famous Śrī Vaiṣṇava temples Godā Vihār and Rangaji. This kuṇḍa is also not very distant from the magnificent temple of Govinda Deva. The narrative connected to this kuṇḍa is that it was here that Kṛṣṇa was captivated by the beauty of Rādhā. As per another narrative, it was at this very kuṇḍa that Vṛndā Devī (Tulasī Devī) appeared before Ṛṣi Nārada. In the 16th century CE, Śrīla Rūpa Gosvāmī discovered an image of Vṛndā Devī at this kuṇḍa. The Mathurā Mahātmya included in the Varāha Purāṇa states that a person who fasts and bathes here enjoys the company of gandharvas and apsarās. A person who dies here attains the loka of Viṣṇu.

Dohinī Kuṇḍa

(Figure 7: Dohini Kund at Chiksauli village of Barsana (Mathura)

Dohinī Kuṇḍa near Barsāṇā is believed to be the place where Vṛṣabhānu, Rādhā ̍s father kept his cows. One day it so happened that Rādhā was observing the milking of the cows and she too felt like doing the same. She took an earthen pot and began to milk a cow. Kṛṣṇa arrived there and seeing Rādhā told her that she was not able to milk a cow and that he will teach her how to do so. Kṛṣṇa sat near Rādhā and together they began to milk a cow. Kṛṣṇa felt like playing a prank on Rādhā and sprayed her face with milk. The Vraja Bhakti Vilāsa considers this place where Vṛṣabhānu milked cows along with the other gopas. The same text locates another Dohinī Kuṇḍa in the region of Nandīśvara or Nandgaon. It is also supposed to be the place where the wishes of the gopīs were fulfilled though we do not know what exactly their wishes were. This kuṇḍa is said to have been created by Vṛṣabhānu himself. This kuṇḍa came to be known as the Dohinī Kuṇḍa as the Vrajavāsis would do the milking (dohana) of their cows here.

Prema Sarovara

(Figure 8: Prema Sarovara)

Prema Sarovara is located in the village of Gazipur which lies between Barsāṇā and Nandagaon. This water reservoir, as per the local belief is said to be the place where Rādhā and Kṛṣṇa first met. The story goes that Kṛṣṇa was aware that Rādhā comes to this reservoir to play with her sakhīs. Rādhā too had heard about Nandanandana Kṛṣṇa. One day, Rādhā, along with her sakhīs arrived at the Prema Sarovara and Kṛṣṇa too reached at the spot. Kṛṣṇa is said to have hid in a kuñja to glance at Rādhā. As soon as Rādhā and Kṛṣṇa came face to face, Kṛṣṇa fell down unconscious. His flute too fell and his clothes were ruffled. Rādhā left Kṛṣṇa in that state and returned to Barsāṇā but her thoughts kept on returning to Kṛṣṇa. As per another local tradition, Rādhā and Kṛṣṇa are one entity but once Rādhā experienced an illusory separation from Kṛṣṇa and in that perturbed state she began to shed tears and the Prema Sarovara was formed out of these tears of Rādhā.

Kusuma Sarovara

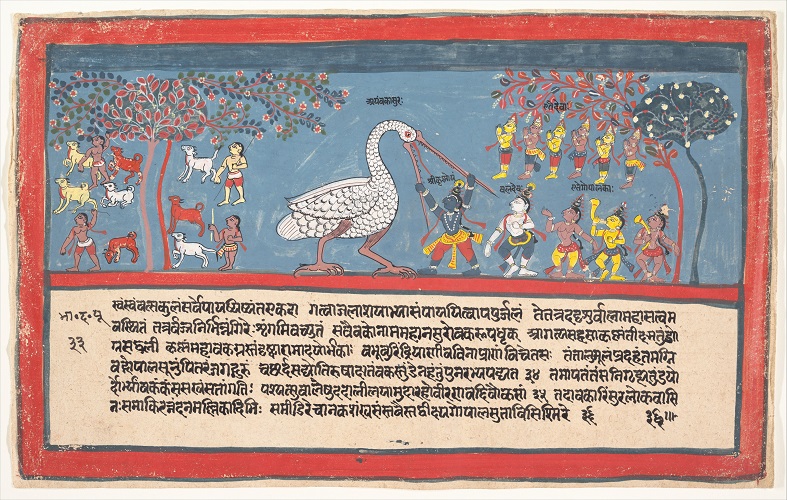

(Figure 9: Kusum Sarovar is one of the sacred spots that witnessed the divine pastimes of Radha and Krishna)

The narrative related to the Kusuma Sarovara is imbued with the transcendental love of Rādhā and Kṛṣṇa. This is said to be the site where Kṛṣṇa had decorated the hair of Rādhā with kusuma or flowers and braided it. As Kṛṣṇa braided her hair, Rādhā is said to have looked into the mirror. Svāmī Haridāsa, the holy musician-renunciate of the 16th century CE has described this particular pastime in one of his compositions. The devotees believe that the site of Kusuma Sarovara is divinized by such līlās of Rādhā and Kṛṣṇa where one finds the preponderance of the śṛṅgāra rasa. As per the Padma Purāṇa which is quoted by Nārāyaṇa Bhaṭṭa in his Vraja Bhakti Vilāsa, the sakhīs of Rādhā would pick flowers at this reservoir and prepare garlands for Kṛṣṇa. It is believed that it was because of this that a forest full of flowers i.e. Puṣpa Vana was created here which became a habitat of devas and gandharvas (celestial musicians). The devotees must worship Rādhā and Kṛṣṇa here along with the gopīs with offerings of flowers. This is also considered to be the site where Śiva would worship Kṛṣṇa and he created a kuṇḍa here for ritual bathing. Historically speaking, the Kusuma Sarovara was visited by Caitanya Mahāprabhu during the course of his Vraja Yātra in the early 16th century CE. This sarovara was equipped with bastions and stairways by the Jāṭ Rājās of Bharatpur. It is here that we have chhatris or cenotaphs of Rājā Surajmal, the Jāṭ ruler of Bharatpur and his queens Hansiyā and Kiśorī.

The Śyāma and Rādhā Kuṇḍas

(Figure 10: Radha Kund, a holy pond dedicated to Radha Rani, near Vrindavan)

If the phrases ̍sanctity ̍ and ̍sacredness ̍ had a visual manifestation then it is certainly embodied in the Rādhā Kuṇḍa situated at the foot of the Govardhana Hill in the pilgrimage town by the same name. A prominent site in the Vraja Maṇḍala Parikramā, the Rādhā Kuṇḍa has been divinized and consequently glorified in the Mahātmya texts about Mathurā, starting right from the 12th century digest, the Kṛtya Kalpataru of Lakṣmīdhara Bhaṭṭa. The Rādhā Kuṇḍa and its adjacent Śyāma Kuṇḍa are visited by countless pilgrims throughout the year and more specially in the month of Kārtika. The background narrative of these kuṇḍas first appears in the Mathurā Mahātmya of the Varāha Purāṇa. The later Mahātmya texts inserted their own creative details into the original narrative. Both these kuṇḍas are associated with the episode of Kṛṣṇa slaying the bull demon Ariṣṭāsura. The līlā of Kṛṣṇa where he killed a violent demon Ariṣṭāsura in the form of a virile bull forms a part of the narrative of all texts delineating the life story of Kṛṣṇa starting right from the Harivaṁśa and coming right down to the early medieval and medieval Purāṇas. The broad outline of the narrative found in the Mahātmya texts states that Kṛṣṇa met Rādhā and the gopīs on the night of the same day that he killed the bull demon. As Kṛṣṇa opened his arms to embrace Rādhā, she declined his advances and said that Kṛṣṇa had killed a bull and had thus committed the deadly sin of Go Hatyā or the sin of killing a cow (here a bull). Kṛṣṇa was ready to atone for this sin and the gopīs instructed him to have a bath in all the tīrthas which were present on the surface of the earth. Kṛṣṇa dug a pond by his foot and summoned each and every tīrtha into it. All tīrthas are said to have flown into this pond after which Kṛṣṇa took a purificatory bath in it. This pond is variously known as Ariṣṭa Kuṇḍa or Śyāma Kuṇḍa though the second name is more well known and in better circulation. The Bhakti Ratnākara reports that while bathing in his kuṇḍa, Kṛṣṇa uttered the name of each and every tīrtha which had made an entry there under his injunctions (Bhakti Ratnākara, Fifth Wave). On seeing the kuṇḍa created by Kṛṣṇa, Rādhā seemed eager to produce a more picturesque and sacred kuṇḍa through her own power. Rādhā, with aid of her sakhīs embarked on digging her own kuṇḍa with her bangles. The sakhīs wished to fill this kuṇḍa with the waters of the Śyāma Kuṇḍa but Rādhā refused and implored the sakhīs to procure water from the Mānasī Gaṅgā. However, in spite of repeated attempts the Rādhā Kuṇḍa could not be filled and this caused great unease to Rādhā and the sakhīs. Eventually like he did for his own kuṇḍa, Kṛṣṇa invoked all the tīrthas to enter the new kuṇḍa and they gladly obliged and the Rādhā Kuṇḍa was thus created. Kṛṣṇa declared that the glory and greatness of the Rādhā Kuṇḍa would far exceed those of his own kuṇḍa. The Rādhā Kuṇḍa is believed to have appeared on the day of Bahulā Aṣṭamī falling in the dark half of the month of Kārtika. A bath in this kuṇḍa confers the devotion and divine love of Rādhā on the devotee. Bathing in both these tīrthas gives the fruit of Rājasūya and Aśvamedha yajñas. The Caitanya Caritāmṛta, the most celebrated hagiography of Caitanya Mahāprabhu attributes the discovery of these two kuṇḍas to him among paddy fields in the medieval hamlet of Arita. Caitanya Mahāprabhu chanced upon these two kuṇḍas during his Vraja Yātrā. Caitanya had both these kuṇḍas cleaned and filled with fresh water (Caitanya Caritāmṛta, Madhya Līlā,18.5). The sacredscape comprising both these kuṇḍas developed as a major settlement of the Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇavas with many savants of this sect having their bhajana kuṭiras and samādhīs around the Rādḥa Kuṇḍa. A popular belief is that the five Pāṇḍavas dwell eternally on the banks of the Rādhā Kuṇḍa in the form of trees. Both these kuṇḍas were surrounded by the kuñjas of the aṣṭa sakhās and aṣṭa sakhīs of Kṛṣṇa and Rādhā respectively, though in the present times there are hardly any traces of these. The Vraja Bhakti Vilāsa calls the Rādhā Kuṇḍa as Śrī Kuṇḍa, ̍ Śrī ̍ being another appellation for Rādhā (Vraja Bhakti Vilāsa, 4.5). Śrīla Rupa Gosvāmīn in his work titled Śrī Upadeśamṛta states that just like Rādhā is most dear to Kṛṣṇa among all the gopīs, so is the Rādhā Kuṇḍa. Rādhā Kuṇḍa is difficult to attain even for the most exalted devotees. For the Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇavas, Rādhā Kuṇḍa is the most sacred tīrtha on the surface of the earth (Śrī Upadeśamṛta, Ślokas 10 and 11).

Balabhadra Kuṇḍa

(Figure 11: Balabhadra Kuṇḍa)

There is a kuṇḍa, known as Balabhadra Kuṇḍa in Tālavana, one of twelve major forests of Vraja and also the site where Balarāma killed the demon Dhenukāsura. This narrative, which is found in texts older texts like the Harivaṁśa was altered and elaborated upon in medieval Purāṇas like the Brahmavaivarta Purāṇa. This was a forest full of Tāla trees. The yātrā to Tālavana is complete only after a bath and ācamana in the waters of this kuṇḍa. The Garga Saṃhitā, a text who ̍s antiquity does not go beyond the 15th century CE, records a narrative with respect to the Balabhadra Kuṇḍa at Tālavana. As per this narrative, Kṛṣṇa once paid a visit to Tālavana accompanied by Rādhā and other gopīs. They all performed a dance here. The dance left the young maidens of Vraja thirsty and exhausted. The gopīs requested Kṛṣṇa to procure water at this site. They said that the Gaṅgā River was too distant from here and they wanted to quench their thirst as well as engage in water sports with Kṛṣṇa. Kṛṣṇa is said to have dug the ground with his vetra or cowherd stick and a water source appeared there. This water source came to be known as the Vetra Gaṅgā and in the present times this water source in the form of a reservoir is known as the Balabhadra Kuṇḍa. This kuṇḍa is supposed to be endowed with great sacredness and a bath here absolves a person from the sin of killing a Brāhmaṇa. Similarly a bath in this kuṇḍa also makes a person eligible for a place in Goloka, the supreme abode of Rādhā and Kṛṣṇa. Though the narrative of this kuṇḍa has Kṛṣṇa and the cowherd girls as the main actors, it nevertheless carried forward the original association of Tālavana and its sacred sites with Balarāma.

- Miscellaneous Narratives

Dharma Kuṇḍa

Dharma Kuṇḍa is a kuṇḍa situated near Kāmya Vana. The local tradition associates this place with the episode of the dialogue between Dharmarāja and Yudhiṣṭhira however the description given in the Mahābhārata is not in conformity with this local tradition. The Vraja Bhakti Vilāsa states that Yudhiṣṭhira had performed some pious acts (Dharma) at this kuṇda. Thus this reservoir is associated with Yudhiṣṭhira and may have also been named as Dharma Kuṇḍa since Yudhiṣṭhira himself was the son of Dharma and enjoyed the epithet of Dharmarāja because of his virtuous and just nature.

Pañca Tīrtha

The Pañca Tīrtha is a reservoir of water located near Kāmya Vana. As per the local tradition, the Pāṇḍavas had performed penance here during their years in exile. This site of penance got transformed into a water kuṇḍa and came to be known as the Pañca Tīrtha after the five Pāṇḍava brothers. The Matsya Purāṇa states that Yudhiṣṭhira performed five yajñas here and took the abhṛta snāna in this kuṇḍa. As per this story, it is because of the five yajñas and the purificatory baths of the Pāṇḍavas that this kuṇḍa came to be known as Pañca Tīrtha.

Yakṣa Sarovara

The Yakṣa Sarovara located in the village of Parkham is considered to be the site where the dialogue between a Yakṣa and Yudhiṣṭhira is supposed to have taken place. The Pāṇḍava brothers with the exception of Yudhiṣṭhira, arrived at this sarovara guarded by a Yakṣa to quench their thirst. They all fell dead because the Pāṇḍavas refused to answer the questions of the Yakṣa. Yudhiṣṭhira arrived at this sarovara in search of his brothers and when he learnt of their fates, he gave fitting replies to each of the questions posed by the Yakṣa. Happy with Yudhiṣṭhira ̍s answers, the Yakṣa brought back to life all the four Pāṇḍava brothers. It is because of the presence of the Yakṣa that this reservoir came to be known as the Yakṣa Sarovara. Parkham, at least since the Śuṅga times was a centre of Yakṣa worship. A colossal image of Yakṣa Maṇibhadra was discovered here by Alexander Cunningham in the 19th century CE. The image is now a part of the collection of the Government Museum, Mathurā. The local tradition calls Parkham a ̍ nagara ̍ of Yakṣas. This tradition preserves within itself the memory of Parkham once being a centre for Yakṣa worship which was widely prevalent in the region of Mathurā in the ancient times.

Gayā Kuṇḍa

This kuṇḍa too is situated within Kāmya Vana. The narrative regarding this kuṇḍa states that a king called Rājā Gayāsena who ruled over the city of Campāvatī got this kuṇḍa excavated in the Satya Yuga. The town of Gayā in Bihar, is well known as the sacred site for the performance of shrāddha rituals. The Gayā Kuṇḍa is said to be no less sacred than the town of Gayā itself. Indra is supposed to have performed the shrāddha rituals at the Gayā Kuṇḍa. Shrāddha rituals and tarpaṇa performed at this kuṇḍa relieve the manes from the torments of Yama and lead them to mokṣa.

Śantanu Kuṇḍa or Samviṭaka Kuṇḍa

This kuṇḍa and its narratives which find a mention in the Mathurā Mahātmya of the Varāha Purāṇa, is present in the village of Satoha. There are two narratives associated with this kuṇḍa though they share a common theme. This is considered to be the site where King Śantanu, the ancestor of the Pāṇḍavas and Kauravas practiced austerities facing the sun and as the outcome of his austerities, he was blessed with a brave and able son like Devavrata (Bhīṣma). After being blessed with this son, Śantanu returned to Hastināpura. As per the other narrative, Kṛṣṇa prayed to the sun god at this site and the latter blessed him with a son who was named Sāmba. Kṛṣṇa had a vision of the sun god who held a lotus in his hand here. Sāmba, in many other Paurāṇic narratives is closely linked to sun worship. There is an archaeological mound at this site indicating that it must have been an ancient settlement.

Observations

Water and the purificatory rituals associated with it are integral to pilgrimage circuits and this holds specially true for Sanātana Dharma. Apart from basic functions like provision of water to the pilgrims for various chores, water bodies occupy a place of distinct sacredness and significance in the pilgrimage circuits or tīrtha yātrās. Apart from pilgrims coming from other lands, these water bodies are very crucial for the day to day lives of the local people. These water bodies are venerated by pilgrims and the local population alike and we find this phenomenon mirrored in the case of the kuṇḍas of Vraja. The local population, especially the elders, are well acquainted with the kuṇḍa narratives and acknowledge the fact that these kuṇḍas constitute inseparable part of their routine lives. The inclusion of several of these kuṇḍas in the Vraja Maṇḍala Parikramā reiterates their importance in the pilgrimage circuit of Vraja.

The narratives of Kṛṣṇa Kathā centering around the kuṇḍas are primarily sourced from the Itihāsa – Purāṇa tradition. Over the course of centuries, a number of oral traditions prevalent in the region of Mathurā merged with the more classical and better known narratives from the Itihāsas and Purāṇas. As we have seen in the case of the Rādhā and Śyāma Kuṇḍas, the Harivaṁśa which serves a sequel to the Mahābhārata as well as the Purāṇic texts contain the narrative of Ariṣṭāsura but it is the Mathurā Mahātmya incorporated into the Varāha Purāṇa that links this episode with the creation of the two kuṇḍas. There is a high possibility that the source of the Mathurā Mahātmya itself was a local oral tradition which it inducted and preserved. Taking the Itihāsa-Purāṇa stories as their foundations, layers and layers of oral narratives accrued over the course of time. It may not be out of place to propose that many of these oral traditions developed in a trajectory parallel to the Itihāsa- Purāṇa model. At the same time one cannot refute the fact that the Itihāsas, especially the Mahābhārata and the Purāṇas represent a literary corpus which owes its origin and diachronic growth to a bunch of oral narratives. Many of the stories pertaining to the kuṇḍas are elaborations and variations of the Itihāsa-Purāṇa literature. As we have noted, a few kuṇḍa narratives are based on the two Itihāsas- namely the Rāmāyaṇa and Mahābhārata. The kuṇḍa narratives are not found in the Itihāsas proper but they assume the role of mediums to integrate the Itihāsas within the sacred geography of Vraja. This phenomenon is not unique to the kuṇḍa narratives and this sort of inclusion of the Itihāsa narratives into the local geography is found in almost all parts of India.

The narratives of the kuṇḍas are deeply entrenched in the pastoral lifeways of the people of the land of Vraja. The region of Vraja was home to numerous pastoral communities like the Ābhiras who, in the opinion of scholars have a major share in the evolution and expansion of the Kṛṣṇa Kathā. As per these narratives, the kuṇḍas along with riparian sites along the Yamunā were sites where Kṛṣṇa and Balarāma brought their herds of cattle for grazing (the Gaurcāraṇa Līlā) and a drink of water. Stories related to the Dohinī Kuṇḍa pulsate with the concerns of the rustic pastoral communities. The life of these communities revolved around their cattle and it is but obvious that these mundane pastoral incidences found a way into the narratives of the kuṇḍas.

The narratives of the kuṇḍas elucidating the childhood pastimes of Kṛṣṇa are filled with the vīra rasa. All the narratives in the first two categories are entirely devoted to the līlās of Kṛṣṇa before his move to Mathurā. His role as Gopāla, living among the pastoral community in the forests of Mahāvana and Vṛṇḍāvana receives more projection. The narratives unfold with Kṛṣṇa as the protagonist and the kuṇḍas become the sites of many of these līlās or alternately they preserve the memory of these pastimes.

Coming to the narratives of Kṛṣṇa ̍s pastimes with Rādhā and the Gopīs, they are imbued with the śṛṅgāra rasa. Thus the narratives falling in this category are predominantly erotic and reflect the varied moods of the couple as they engage in their love play. The kuṇḍas become the spatial settings for the covert pastimes of the divine duo. They become the very spots where Rādhā and Kṛṣṇa meet for a nocturnal pastime. A līlā like Kṛṣṇa decorating the hair of Rādhā with flowers near the Kusuma Sarovara may seem too simple superficially but for the devotees these śṛṅgāra pradhāna līlās are invested with great spiritual meaning. Among the devotees of Kṛṣṇa, especially those who are members of the Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇava Sampradāya, the Gopīs epitomise the highest level of prema bhakti. The Rāsa Pañcādhyāyī featuring in the daśama skandha of the Bhāgavata Purāṇa carries a detailed exposition of the Rāsa Dance, which is in fact a motif to express the devotion of the gopīs i.e. the Jīvātmas for Kṛṣṇa who is the Parabrahman or Paramātmā. Many of the kuṇḍas owe their origin to the cure of the exhaustion felt by the gopīs after the rāsa dance. The kuṇḍas are also the chosen sites for the son of Nanda to enjoy the Mahārāsa with the young cowherd girls of Vraja.

Many of the kuṇḍa narratives have emerged in such a way as to induct and accommodate relatively newer characters like the sakhīs and parents of Rādhā as well as the sakhās of Kṛṣṇa who do not appear in the older texts like the Harivaṁśa. Many of the pastimes which are said to have been performed at kuṇḍas have an active participation by the sakhīs of Rādhā whose principal task is to ensure the union of the couple and take care of their needs and comforts. Sites like Nandgaon (the hill of Nandīśvara) and Barsāṇā (the hill of Brahmeśvara) came to the fore in the medieval period as locales divinized by the pastimes of Kṛṣṇa and Rādhā respectively. The narratives reflect the inclusion of kuṇḍas located at both these sites and the generation of a fresh group of narratives to facilitate the induction of newer characters and newer localities within the sacredscape of Vraja.

The kuṇḍa narratives like the one regarding the Āseśvara Kuṇḍa function as mediums to integrate the other religious sects like Śaivism with the Kṛṣṇaite landscape of medieval Vraja. This kind of amalgamation of Śaivism with Kṛṣṇaism was a way for the reconciliation of these two sects prevailing in the land of Vraja. Rather than rejecting Śaivism altogether by not acknowledging its fairly noteworthy and conspicuous presence in the religious milieu of Vraja, Śiva was assimilated into the Kṛṣṇaite fold by bestowing on him the role of a Parama Vaiṣṇava. Apart from these kuṇḍas, there are mainly other sites in Vraja which are considered to be places where Śiva mediated on Kṛṣṇa.

One of the recurrent themes in the kuṇḍa narratives is about their origin. The general thematic trend occurring with respect to the kuṇḍas is that they are either created by Rādhā, Kṛṣṇa or any of their associates or have emanated from their tears or bath waters. The sacredness of the kuṇḍas is mainly because they have been either created by Rādhā or Kṛṣṇa or have been formed from their tears or remnants of the bath waters. Thus the kuṇḍas, for the faithful, are liquid manifestations of the ethereal pair and are not independent from them. The Kṛṣṇa Kathā heightens and supports the water symbolism which is inherent to the kuṇḍas. The origin of some of the kuṇḍas is ascribed to their production from either the body of a divinity, more specifically Kṛṣṇa or from the water used by a divinity for his or her bath. There is one such kuṇḍa called Sītā Kuṇḍa in a forest called Aśoka Vana near Vṛndāvana and this is supposed to have been formed out of the water used by Sītā for her bath. Similarly there are more than one Kṛṣṇa Kuṇḍas, Rādhā Kuṇḍas, Nārada Kuṇḍas and Yaśodā Kuṇḍas which have similar narratives.

We will now consider the role of the kuṇḍa narratives in the construction of the sacred geography of Vraja. The Indian narrative is moored in space more than time (Paniker, 2010:3). In the opinion of Ayyappa Paniker, the element of time is often that of a long bygone era which has a deep antiquity. This is especially true about the temporal dimension with respect to the Purāṇas. Some of these narratives have been brought within the fold of Sthala Mahātmyas of Vraja (in most cases the word Mathurā is used and not Vraja). Almost every site falling within the pilgrim circuit of the Vraja Maṇḍala Parikramā has at least one kuṇḍa which is invariably connected to some or the other pastime of Kṛṣṇa alone or Kṛṣṇa and Rādhā jointly. The kuṇḍa narratives have a specific spatial context and are placed within the physical landscape of Vraja. In fact it is these narratives of Kṛṣṇa Kathā which make these kuṇḍas, which in most cases are no more than a pond, sacred. On the physical plane, the kuṇḍas being sources of water are intrinsically sacred as water is considered not just as one of the five fundamental elements that sustain this world but also because of the purificatory quality of water. However it is the Kṛṣṇa Kathā which significantly adds to the sacredness of the kuṇḍas. The kuṇḍas become the actual space where the incidents in the Kṛṣṇa Kathā have once taken place or are still taking place. The kathās have contributed in the preservation and safeguarding of these kuṇḍas which otherwise could have succumbed to the uncontrolled and haphazard urbanization of Vraja. The whole sacred landscape of Vraja has in fact been built on and bolstered by the Kṛṣṇa Kathā. The Kṛṣṇa Kathā, as is prevalent in Vraja today is a conglomeration of diverse traditions rather than a monolithic, homogeneous sequence of events. Every constituent of the Vraja Yātrā, from a roadside shrine to a lofty temple has a narrative from Kṛṣṇa Kathā associated with it. The Vraja Yātrā circuit itself is highly inclusive in nature. The Vraja Yātrā is a collective practice which can be performed by any member of the society without considerations of ethnicity, gender or caste. It is through these narratives of Kṛṣṇa Kathā that the kuṇḍas irrespective of their physical forms have earned a place within the Vraja Maṇḍala Parikramā. Many of the kuṇḍas confer some kind of merit by the performance of ritual acts like snāna, dāna and ācamana in their waters. Many a times the narrative itself in a way illustrates the manner in which one of the players in Kṛṣṇa Kathā, especially Rādhā or Kṛṣṇa themselves carried out these acts. It is through these narratives that the kuṇḍas themselves attain the stature of objects of veneration. Some of the water bodies like the Mānasī Gaṅgā are supposed to be the water of the Gaṅgā River which was summoned by Kṛṣṇa using the power of his mind. Thus the Gaṅgā River which is physically not a part of the landscape of Vraja, notionally gets incorporated into its sacred landscape. Similarly Kṛṣṇa ̍s act of making all the tīrthas of the world enter into the Śyāma Kuṇḍa echoes a similar process of site replication. The tīrthas are not existent in the physical geography of Vraja but they are certainly present in the sacred geography of this region and the faithscape of the devotees.

One of the unique features of the kuṇḍa narratives is that the śṛṅgāra rasa predominates the mood of the narratives. This is in conformity with the broad theme of the narratives that have emerged in the Vraja region since the last few centuries. Kṛṣṇa assumes the role of the quintessential nāyaka and Rādhā is perceived as the ideal nāyikā. Compared to the narratives concerning other components of the Vraja Maṇḍala Parikramā, the kuṇḍa narratives are more popular. One reason for this may be the innate sacredness of the water in these kuṇḍas. Many of the kuṇḍas are venerated as the liquid forms of Rādhā and Kṛṣṇa and the kuṇḍa narratives have played a key role in strengthening this belief. Medieval settlements sprung up around these very kuṇḍas and the growth of these settlements is ascribed to two factors – one is the availability of water and the second is the sacredness associated with the water source which is spelled out in the narrative of that particular kuṇḍa. The qualifying feature of every constituent in Vraja to be considered as sacred is its invariable association with Rādhā and Kṛṣṇa primarily and the kinsmen and friends of Kṛṣṇa secondarily. The theological foundation of medieval Vraja was constructed on the worship of Rādhā and Kṛṣṇa jointly. The religious structure of Sampradāyas like the Gauḍīya Sampradāya, the Sakhi or Haridāsi Sampradāya, the Rādhā Vallabha Sampradāya as well as the Nimbārka Sampradāya is deeply entrenched in the upāsanā of Rādhā and Kṛṣṇa. This phenomenon has also made its way into the kuṇḍa narratives where the divinity of Rādhā and Kṛṣṇa outshines the other elements.

The kuṇḍa narratives have integrated almost every element of the Vraja Līlā of Kṛṣṇa. Stories based on Kṛṣṇa ̍s childhood, the Rāsa dance and his play with Rādhā and the sakhīs have all found a place in the kuṇḍa narratives.

The narration of the Kṛṣṇa Kathā, along with Kīrtana is an indispensable facet of the Vraja Maṇḍala Parikramā. Many religious leaders and ascetics are adept at narrating the Kṛṣṇa Kathā, especially in the vicinity of the kuṇḍas. The general practice is that they render the kathā of a līlā which is believed to have occurred at that particular kuṇḍa. The kuṇḍa itself has potency, but this potency is intensified by the narrative. The kathā makes a devotee turn away from the gross material world and experience the transcendental pastimes of Rādhā and Kṛṣṇa. The devotees believe that in the age of Kali that we live in today, one will not be able to get a vision of Kṛṣṇa and Rādhā through the material eyes. However it is through the kathā that the līlās of Rādhā and Kṛṣṇa come alive. For the sādhakas of rāgānugā bhakti, the līlās of Rādhā and Kṛṣṇa are nitya or eternal and it is in this spiritual realm that the devotees are supposed to get engrossed through the medium of the kathā. The kathā enables a sādhaka to develop Kṛṣṇa Preman or the divine love for Kṛṣṇa.

Listening to the kathā in the space where the incidents of the kathā are believed to have taken place, adds to the impact the kathā has on the mind of the devotees. The kuṇḍa narratives of Kṛṣṇa Kathā have to be perceived from the perspective of bhakti. Śravaṇam or listening to the glories of Viṣṇu and his exploits is the first stage of the process of Navavidhā Bhakti which is believed to have been preached by Prahlāda to his father Hiṇraṇyakaśipu (Bhāgavata Purāṇa, 7.5.23). Listening attentively to the Kṛṣṇa Kathā is thus the preliminary step in the advancement of realizing Kṛṣṇa Preman. For a non-believer, these kathās may seem like random stories which are the outcome of the fantasy and imagination of the rustic villagers of Vraja. However for the Vrajavāsīs and devotees, these kathās are nothing less than real. All the kuṇḍa narratives, for the devotees are rooted in great antiquity when Kṛṣṇa, who is Svayama Bhagvān walked on the sandy banks of the dark Yamunā, gleefully herded cows in the vast expanses of the Vraja forests, danced energetically with the cowherd girls and left all the Vrajavāsīs- humans and beasts alike enchanted and captivated by the melody of his flute. The kathās transport the devotees to the transcendental domain of Kṛṣṇa who is none other than the Para Brahman. The kuṇḍa narratives are thus transcendental, the waters of the kuṇḍas are transcendental and they are permeated by the presence of Kṛṣṇa, who is himself the eternal repository of transcendental bliss.

List of References

Bhatt, Narayana. Vraja Bhakti Vilasa. Kusuma Sarovara: Krishnadasa Baba. V.S. 2004

Cakravarti, Narahari (Kusakratha Dasa trans.). Bhakti-Ratnakara. Vrindavana: Ras Bihari Lal & Sons. (Date of publication not mentioned)

Garga Samhita. Mumbai: Shri Venkateshvara Press.(Date of Publication not available)

Growse,F.S. Mathura: A District Memoir, Part I, North Western Provinces’ Government Press, 1874.

Gupta, Munilal (trans.), The Vishnu Purana. Gorakhpur: Gita Press, V.S. 2072.

Jagatananda, Vraja Vastu Varnana. (Details of publication not available)

Jha, Surkant (ed.), Varahapuranam. Varanasi: Chowkhama Krishnadas Academy, 2014.

Krsnadas Kaviraja and A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada (trans.), Sri Caitanya Caritamrta, Madhya Lila, Volume Three, The Bhakti Vedanta Book Trust, Bombay, 1975. (Reprint 2014)

Loknath, Swami. Vraja Mandala Darshana. Noida: Padayatra Press, 2018 (2nd Edition).

Paliwal, Raina. Rasa Braja Raja Kou. Agra: Amar Ujala Publications Ltd., 2015.

Paniker, Ayappa K. 2010. “India Narrates Itself”. In Narratology: Indian Perspectives : Edited by C. Rajendran, 1-11. Delhi: New Bharatiya Book Corporation.

Rajendran, C. 2010. “Narratology-Some Precepts and Practices in Ancient India”: Narratology: Indian Perspectives : Edited by C. Rajendran,12-20. Delhi: New Bharatiya Book Corporation.

Ray, Sugata. Climate Change and the Art of Devotion: Geoaesthetics in the Land of Krishna. 1550-1850. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2019.

Rupa, Gosvami (author) and A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada (trans.). Sri Upadesamrta. Mumbai: The Bhakti Vedanta Book Trust, 2016 (13th Reprint).

Thavre P.K and Desai V.G. (trans), Srimad Bhagavata Puranam, Volume II, Gorakhpur: Gita Press, V.S. 2072.

Vaidya, P.L. (ed.), The Harivamsa, Volume I. Poona: Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, 1969.

Feature Image Credit: facebook.com

IndigenousStorytellingTraditions

Watch video presentation of the above paper here:

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.