Abstract

The greatness of the Indian Temple architecture lies in the spirituality embedded in its elements. The ever-evolving religious and spiritual thoughts of the Indian rishis and spiritual philosophers were dynamic. The Sthapatis and their teams tried to give concrete shape to their religious consciousness through their edifices and were able to match their thoughts with the architectural elements in the temple. The intangible religious beliefs were made tangible in a temple

In this paper, the discussion will be centered around:

- The symbolism in art and architecture of Chausath Yogini temple at Hirapur.

- The right way to take darshan in the Chausath Yogini Temple, Hirapur.

- How the temple architecture levitates devotees’ minds from Sthul to Sukshma to Para where the Ultimate Reality resides.

(The symbolism of the Hypaethral form

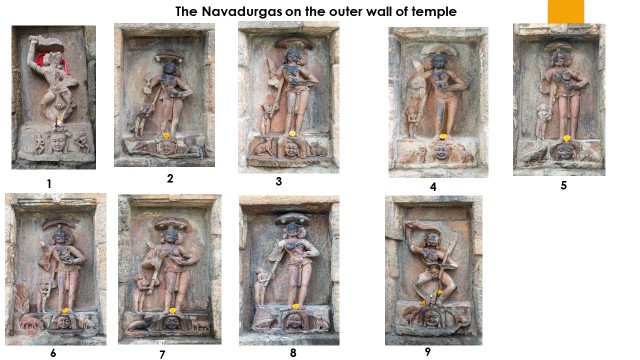

The symbolism of the Nava Durgas on the outer wall of the temple

The symbolism of the narrow passage to the circular shrine

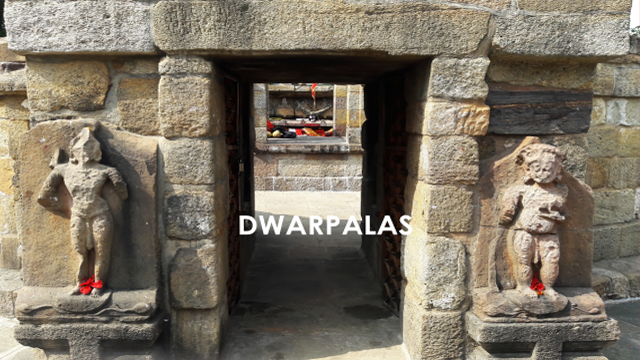

The symbolism of the dwarpalakas at the gate

The symbolism of two nude male images in the vestibule

The Symbolism of Chandi Mandap and Yogini Mandap

The symbolism of four Bhairavas on four pillars of Chandi mandapa)

Yogini Worship

The origins of the Yoginì worship remain enigmatic, and its specific practices during the early medieval times are not entirely understood. This ambiguity largely stems from the lack of ancient manuscripts detailing the rituals associated with the worship of yoginìs. However, these deities are frequently referenced in subsequent Vedic and post-Vedic texts as representations of feminine energy.

Yogini worship, in the form recognized in Sakta-tantric traditions, emerged in India around the 6th to 7th centuries A.D. It thrived as a mystical and esoteric tradition centred on the veneration of intense forms of Shiva and Shakti. It is believed that those who practised this form of worship were endowed with magical and supernatural abilities, especially to defeat adversaries, through the collective power of the Shaktis known as yoginis.

Vidya Dehejia posits that the Yogini sect, deeply rooted in tantric practices and the ancient belief in the power of magical rituals, gestures, and sounds, has strong ties to rural and tribal traditions. She suggests that the inception of Yoginis can be traced back to local village deities or “grama devatas.” These local deities, revered by villagers for ensuring the well-being of their community and bestowing unique blessings, appear to have evolved into powerful groupings of sixty-four, and sometimes forty-two or eighty-one. Tantrism played a pivotal role in enhancing the stature of these local deities, reshaping them into a collective of goddesses capable of granting magical abilities to their devotees. The beliefs, practices, and veneration of these and other deities, which were initially outside the Brahmanical tradition, were later integrated under the umbrella of Tantra, thereby gaining recognition and legitimacy in subsequent Hindu traditions.

Yogini

In many Indian traditions, ‘yogini’ typically denotes a mystical female figure with roles ranging from sorceress to fairy, witch, or even demon. The term can also refer to a group of female devotees of Durga, or in some contexts, Durga herself. Originating from ‘yoga’, it highlights a connection to “mystical arts”, underscoring their ambiguous powers, both benevolent and malevolent. Yoginis are associated with specific Sakta-tantric practices that ward off negativity. Between the 8th and 13th centuries, their importance in India surged, marked by the construction of dedicated open-air temples. Yet, their significance waned after the 13th century, leading to various misunderstandings about yoginis, exacerbated by broader misconceptions about tantra.

Magical abilities of Yoginis

Skanda Purana mentions the magical abilities of the Yoginis are described such as-Vashikaranam (the power of subjugation through attraction), Gutikanjana (a type of collyrium applied to the eyes that enables one to locate buried treasures), Dhatuvada (alchemic power), Vidagdha (the power of destruction), Agnistambhamam (the power to stop fire), Jalastambamam (the power to stop the water), Vakstambhamam (the power to render speechless), Khechritvam (the ability to fly in the air), Adrushyatvam (invisibility), Akarshanam (the power of irresistible attraction), Uccatanam (the power to drive a man away from his home), Nijangasaundaryam (to make one’s person beautiful), Yuvacittavimohanam (infatuating the youthful mind) etc.

The goal of yogini worship, as described in both Puranas and Tantras, was the acquisition of siddhis. The Sri Matottara Tantra outlines eight principal powers, similar to those mentioned in Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras. These are 1. Anima: The ability to become minuscule, providing insights into the universe’s workings. 2. Mahima: The capacity to enlarge oneself, offering a panoramic view of the solar system and beyond. 3. Laghima: Achieving weightlessness, facilitating levitation and out-of-body experiences. 4. Garima: The power to become incredibly heavy and formidable. 5. Prakamya: Possessing an unyielding will, enabling one to influence others’ thoughts. 6. Ishitva: Mastery over one’s physical and mental being, as well as over other creatures. 7. Vashitva: Dominance over natural forces, such as controlling weather events or geological phenomena. 8. Kamavashayita: The capability to attain any desired object or treasure.

The Sri Matottara Tantra lists many other more or less magical powers that devotees can obtain by invoking the yoginis correctly, from the ability to cause death, disillusion, paralysis, or unconsciousness to provocation, delightful poetry, and seduction.

Panchamakara Sadhana

Yoginis are worshipped using Panchamakara, panch means five and Makara means initial letters of each five items. In the context of Tantra, it refers to five substances corresponding to five different elements in certain tantric rituals.

1. Madya (Fire element) wine or alcohol. 2. Mamsa (Earth element) meat. 3. Matsya (Water element) fish. 4. Mudra (Air element) parched grain. 5. Maithuna (Ether element) sexual intercourse. Panchamakara sadhana is practised to transcend the limitations of the physical and reach higher spiritual states.

Textual References of Yogini Sect

That the worship of sixty-four yoginis was widely prevalent is evident from several lists of yoginis recorded in different texts. The Kalika Purana, Skanda Purana, Brihadnandikeswara Purana, Chausatha Yogini Namavali, Chandi Purana of Sarala Das, Durgapuja, Brihndla Tantra, Bata Avakasa of Balaram Das, and other texts contain lists of sixty-four Yoginis. Of the twelve surviving Yogini temples, the Chausath Yogini temple in Hirapur, Odisha, is believed to be among the oldest dedicated to these deities.

Chausath Yogini Temple, Hirapur

(Figure 1: Chausath Yogini temple, Hirapur)

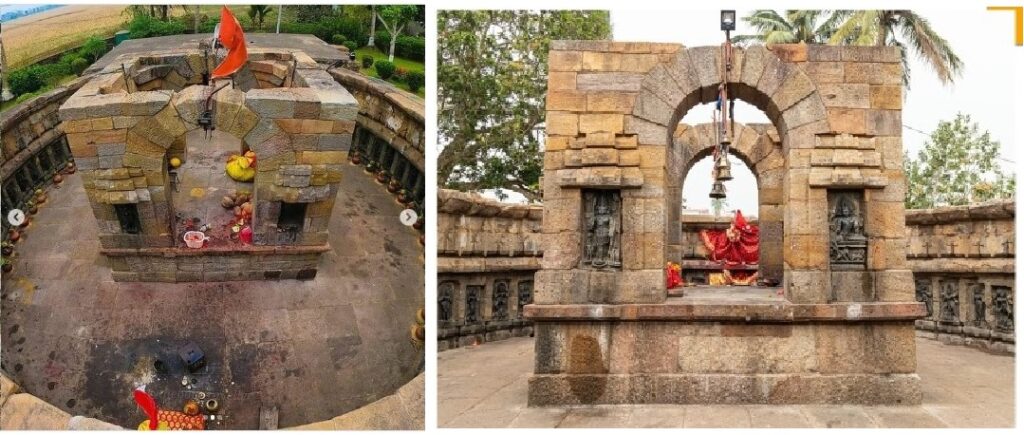

Chausath Yogini temple is located between Bhubaneshwar and Puri—Ekamrakshetra and Purushottamakshetra, both known to be prolific centres of tantrism in their times—in the Hirapur village of Khurda district, Odisha. Chausath Yogini temple in the village of Hirapur is the smallest of the Yogini temples found in India. It was discovered for the public by Kedarnath Mohapatra an archaeologist in 1953 who dated the temple to be from the 9th century A.D., where the Bhaumakara kings established the earliest pìtha consecrated to this sect in the region. It is the only living yogini temple in the country where yogini Mohamaya is worshipped as a presiding deity and serves as a grama devata in the locality. It is located close to the south bank of river Kuakhai. This temple is unlike the other major Kalinga-style architecture which is circular and hypaethral which means it has no roof. The temple is built of blocks of coarse sandstones and a base made of laterite. The outer circumference of the temple is 90 feet with a projection of 4 feet in length and 2 feet 6 inches in breadth. The temple rises to a height of 27.3 meters from above the ground and a diameter of 30 feet.

The circular roofless temple has a narrow entrance facing east flanked by Dwarpalas. Nine Navadurgas were carved in nine niches on the outer walls. Low Antarala with two Bhairavas. Yogini Mandap with sixty Yoginis in their niches and square roofless Chandi Mandap with four Yoginis and four Bhairavas on its pillars.

(Figure 2: Circular and Hypaethral Kalinga-Style Architecture)

Symbolism in the art and architecture of the temple

The greatness of the Indian Temple architecture lies in the spirituality embedded in its elements. The ever-evolving religious and spiritual thoughts of the Indian rishis and spiritual philosophers were dynamic. The Sthapatis and their teams tried to give concrete shape to their religious consciousness through their edifices and were able to match their thoughts with the architectural elements in the temple. The intangible religious beliefs were made tangible in a temple.

Temple architecture also through its various layers both internally and externally takes the devotee from Sthul to Sukshma to Para which is from gross to subtle to causal. The causal or Para, the ultimate reality is when human consciousness resolves into divine consciousness. Therefore, every element of the temple architecture has a physical presence with a symbolic meaning behind it.

As per the scriptures, there is a right way to take the darshan of the deity in the temple. Today in this paper we are going to look at the right way of taking darshan in Chausath Yogini temple, how various architectural elements are designed as per the belief of the Yogini sect and how it takes the devotee through its various layers to the Bindu-The Ultimate Reality.

Mahamaya Pushkarini Kund

(Figure 3: Mahamaya Pushkarini Kund)

To take darshana in a temple both mental and physical purity is a must. Most of the Hindu temples are provided with a temple tank, a kund, or it is located near the water body. A pond is considered the symbolic representation of the sacred rivers Ganga and Yamuna. Taking a dip in the kund is akin to taking a holy bath in these rivers and is believed to cleanse oneself physically and spiritually. The temple pond’s water is often associated with the divine and the primordial waters of creation. Taking a dip can symbolize awakening to higher consciousness and a deeper connection with the divine and the universe. Hirapur temple is located amidst paddy fields beside Mahamaya Pushkarini pond. Devotees take a dip in the water and then proceed to the temple.

Pradakshina Path around the Temple

(Figure 4: Pradakshina Path around the Temple)

The whole temple is but an extension of the deity in the Garbhagruha; hence the Pradakshina around the temple as a whole is also considered sacred. It is advised that the devotee does the pradakshina of the temple from outside first and then enters the temple to take the darshan of the deity in the Garbhagriha.

(Figure 5: Jangha, the wall of circular enclosure featuring the Navadurgas)

The temple, though of a much lesser height as compared to the other temples of Bhubaneswar, has a pitha and jangha. The pitha, the base of the temple, is devoid of any decoration. Jangha the wall of the circular enclosure features nine niches, home to the nine fearsome female protectors known as Navadurga. Navadurgas are two armed figures standing on severed heads. At the base of each Durga image is a severed head, flanked by dogs and jackals, animals found near the carcasses of dead bodies. Each Durga is holding a raised weapon in her hand indicating the head on which she is standing is recently beheaded.

As the devotee circumambulates the temple he contemplates on the different forms of Nava Durga engraved. Navadurgas are nine manifestations and forms of Durga. According to Hindu mythology, the nine forms are considered the nine stages of Durga during the nine-day-long duration of the war with demon-king Mahishasura, where the tenth day is celebrated as the Vijayadashami (lit. ’victory day’) among the Hindus and is considered as one of the most important festivals.

(Figure 6: The Navadurgas on the outer wall of the Temple)

Navadurgas are the protective deities or the guardian deities of the temple and their dynamic poses show them beheading a human and depicted as standing on it. She warns the devotee to not take his initiation lightly and to kill their ego before entering the shrine. The ferocious nature of the devi along with the crematorium imagery like jackal and dog shows the shava sadhana or the tantric rituals that take place in a crematorium. Doing the Pradakshina and contemplating on the Navadurgas, assures us of her protection and makes our mind conducive to receving darshana in the shrine.

Dwar and the Dwarpalas

(Figure 7: The low entrance of the shrine flanked by Dwarpalas)

Before entering the shrine, we must first pass through the door or Dwar, which is the place of entry and a place of display. The low entrance of the shrine is flanked by Dwarpalas, the doorkeepers, the semi-divine beings, servants of gods, and part of the Parivar Devatas. They are formidable-looking guards in service of the temple’s presiding deity. They are always shown in pairs and their appearances, attire, weapons, and emblems showcase the power and magnificence of the main deity in the Garbhagriha.

The temple entrance in the East is flanked by two guardians or dwarpalas on both sides. The Dwarpala on the southern side (left) depicts a two-armed male figure with ear ornaments and a lotus creeper on the pedestal. On the northern side (right) Dwarpala is a wrathful male figure with a fierce look, dishevelled hair, a protruding stomach, and holding a skullcup in his left hand. There is also a lotus creeper on the pedestal.

Dwarpalas warns the devotee to take a minute and reflect before he crosses over the threshold and not to take this initiation lightly. By crossing the threshold, the devotee is initiated into the most sacred place of the divine order. Dwarapalas protect the energy of the temple and remind the people entering the temple that this is the place of Devata, so while entering the main shrine, the devotee should be in a reverential, grateful, and submissive frame of mind. Therefore, permission is sought from Dwarpalas before entering the shrine.

Antarala

(Figure 8: Antarala – a gateway that connects the entrance to Yogini Mandap)

The entrance to the lowly built temple is through a small and narrow entrance. One needs to stoop to pass through, with the passage only accommodating one person at a time. In Hindu temple architecture, Antarala, also known as an antechamber or vestibule, serves as a transitional space that connects the entrance to Yogini Mandap. This intermediate space holds symbolic significance and acts as a buffer zone, preparing worshippers for the sacred experience of the spiritual journey from the outer materialistic world towards the divine inner world of Yogini Mandap and Chandi Mandap. A journey from communal places to a sacred space. Journey of worldly experience to personal spiritual experience.

The Antarala has two ferocious Bhairava figures. The right side figure is Kala Bhairava shown having a skull garland and anklets of snakes. He looks fierce with a sunken belly, matted hair, and an emaciated body with fighting gestures. He holds a skull cup in his right hand. On the pedestal, there is a jackal and two attendants with Katari and skull cups. Both the figures holding skull cups and jackals are reminiscences of Shava sadhana done in the crematorium.

Bhairavas reminds the devotee once again not to take the initiation lightly. The low height of the Antarala due to which one has to stoop to enter symbolizes that one should leave their ego and enter the temple with humility and total devotion or samarpan. Here we leave behind the sthul elements of the materialistic world and enter the sacred space of the temple.

Hypaethral Roofless temple

Hirapur’s Yogini temple is a tantric shrine, with hypaethral (roofless) architecture as tantric prayer rituals involve worshipping the Bhumandala (environment consisting of all the five elements of nature – fire, water, earth, air, and ether). The panch Makara used in Yogini worship also corresponds to the five elements of nature.

A circle protects whatever is inside, whether it’s energy or power. The unique architectural feature, absence of a roof ensures an unobstructed channel for energy flow. Ancient texts suggest that through this open portal, Yoginis were believed to have the ability to soar into other dimensions and return in groups after their celestial journeys.

The shape of the temple resembles 1. Yoni Patta on which Shivlinga rests. 2. A circle. 3. Mandala.

A. Yoni Patta on which Shivlinga rests

(Figure 9: Aerial view of Yoni Patta on which Shivlinga rests)

One is permitted in the circular temple through a small projecting entrance. The aerial view of the temple with the Chandi Mandap in the middle of the circular temple resembles a Shiva linga on a Yoni pedestal. The shape represents Shiva encircled by Yoginis who are the projections of Shakti who forms a mystic womb that holds male Purusha in its depth and from which the whole Universe comes forth. The temple represents the perpetual union of Shiva and Shakti-The Union of eternal bliss.

B. Circle

(Figure 10: The circular design of the temple representing wholesness)

The temple adopts a circular design. A circle symbolizes wholeness and perfection, where nothing is missing, and nothing extra can be included or removed. This shape is frequently evoked to depict Bimba. The circle represents an entire cosmos and is complete in itself without the beginning and the end. It separates sacredness from the profane. Its ultimate representation lies in the idea of cyclical eternity and the singular source of all existence. The circle serves as a protective boundary, particularly in magical ceremonies where it’s crucial to keep the mystical energy concentrated and prevent its dispersion. This concept is further highlighted by the ancient practice of circumambulation, where devotees ritualistically walk around the worshipped object before and after offering their reverence in front of it.

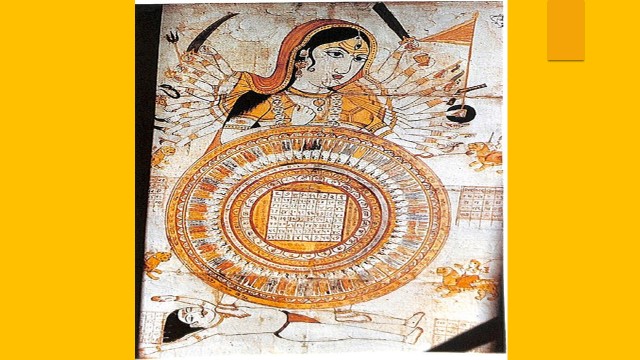

In the Yogini Tantra, a Yogini chakra or Yogini Temple is created by placing images of various yoginis within a circular arrangement. The circle is divided into sixty-four divisions known as ara (ray) or dala (petal). Yoginis are placed in these sixty-four divisions. There are eight matrikas devis and these Matrikas have eight deputies called yoginis which make sixty-four yoginis.

In a circle all are equal hence it is advised that anyone participating in the Yogini chakra puja should leave behind their varna/jati and enter as equal. Therefore the shape of the Chausath Yogini temple is in the form of a circle.

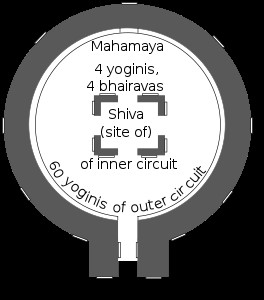

C. Mandala

(Figure 11: Mandala)

A mandala is a geometric arrangement of symbols. It is used to concentrate the minds of seekers and experts, serving as a spiritual guide, creating a holy environment, and assisting in meditation and the initiation of trance states. The word “mandala” comes from the Sanskrit term for “circle”. Mandalas often have a central point or Bindu from which patterns radiate symmetrically.

In mandala worship, the sadhaka must enter through the outer portals, meditate on each consecutive configuration, and proceed gradually inwards. The sadhaka desirous of achieving siddhi has to worship a set of Yoginis at various concentric layers and push onwards towards the centre. A sadhak through rigorous sadhana can reach the Bindu (dot) at the centre which signifies super enlightenment.

A mandala generally represents the spiritual journey, starting from the outside to the inner core, through layers. Hirapur temple also represents a mandala in its architecture, a cosmological map. The Ashta Matrikas symbolize different energies within the mandala. A sadhak through his sadhana starts from the outer concentric circle and progresses through various layers to finally reach the core or the Bindu that represents the ultimate reality. In this scheme, the temple appears to adhere to a mandala layout where concentric circles are formed around the central figure of Shiva (Bindu) in the inner sanctum. This core is encircled by four yoginis and four Bhairavas, creating the first circle. The second circle is of sixty yoginis. The subsequent circle consists of Nava Durgas and two Dvarapalas.

D. Martanda Bhairava

At the centre of the circle, there is a square-shaped Chandi Mandap which is open to the sky like the temple. Chandi Mandap houses four Bhairavas and four Yoginis. At the centre of the mandap, the presiding deity is missing. Ranipur Jharial Chausath Yogini temple in western Odisha has a dancing Martanda Bhairav in the centre of the square pavilion. There is a possibility of Martand Bhairava as a presiding deity at Hirapur temple. ‘Martanda’ is one of the names of the Sun god, and ‘Bhairava’ is a ferocious form of Shiva that is associated with yoginis—this points towards a syncretic solar-cum-saiva tantric deity. The solar character of the temple can be ascertained from the fact that it is East facing, the direction of the rising Sun. In front of the temple, towards the east is a platform called Surya Pitha or the Sun platform which was used for Sun worship by the Sadhaks or devotees. Konark Sun Temple is not too far from here and so Sun worship must have been prevalent in the region.

Yogini Mandap

(Figure 12: Yogini Mandap)

When a devotee passes through the darkness of the Antaral and lifts his head he is met with a mesmerizing sight of the bright roofless spacious interiors of the temple open to nature elements. He encounters sixty distinct yoginis carved from black granite, arranged in a circle. While at first glance they appear identical, closer inspection reveals unique postures and bases. Each two-foot-tall Yogini stands on various animal mounts, but time has damaged some statues. These idealized female figures with full breasts, thin waists, and big hips, epitomizing Hindu sculptural beauty, are mostly naked, adorned only with jewellery and light skirt decorations. Their distinct hairstyles, weapons, and accessories set them apart. Apart from these, four additional Yoginis reside in the Chandi Mandap pillars. The majority of Yogini statues at Hirapur have two arms; nineteen have four arms and the remaining forty-three have two. Some yoginis have human faces, while others feature bird or animal faces.

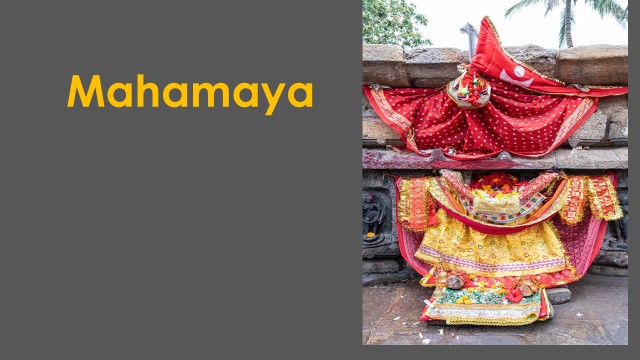

The majority of Yogini statues at Hirapur have two arms, though some have four. Notably, one prominent figure of Mahamaya, located in niche 31 and facing the entrance, has ten arms and is especially larger than the rest. This dominant deity stands on a fully bloomed lotus. In terms of iconography, this statue aligns with the fourteenth-century Kalika Purana’s depiction of Mahamaya. Kali, as early as the sixth-century Devi Mahatmya, was equated with the Maya principle, a cosmic illusionary power stemming from the god Vishnu, and was personified as Mahamaya. Locals continue to revere her as their village deity under this name and she is the only one with an altar before her.

(Figure 13: Depiction of Mahamaya)

Yoginis in this temple personifies both the Saumya (propitious) and Ugra (terrible) aspects of the Shakti.

The ones that are in war mode are Agneyi, Chamunda, Bhalluka, Aghora and Vindyavalini. Some of the Yoginis known for their unconventional traits are shown in an intimidating or fierce manner. Some, like Charcika, Chandika, and Tara, despite their known aggressive characteristics, are depicted more calmly and peacefully.

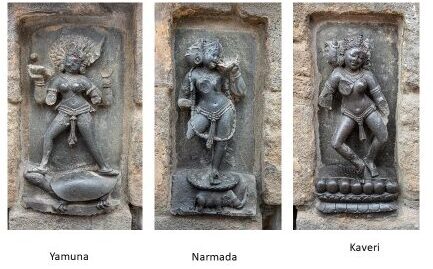

(Figure 14: Yoginis symbolizing river deities – Yamuna, Narmada and Kaveri)

At the Hirapur shrine, several yoginis symbolize river deities. Examples include Gaṅga, represented atop a Makara; Yamuna on a tortoise; Narmada and Sarasvati depicted on wave patterns; Kaveri shown on a sequence of seven Ratna-kalasas (vases brimming with treasures); and another unnamed goddess portrayed on a crab. All these figures can be understood as representations of river or aquatic deities.

Yoginis often bear symbols associated with the Kapalika sect and have a deep connection with Bhairava, frequently represented as the leader of their ensemble in many Chausath Yogini temples. Adorned with skulls, bone jewellery, and carrying khatvanga, these Yoginis exude strong tantric themes. Recognized for their intense and unpredictable nature, they elicit a mix of respect and unease. Names such as Raktapriya, Surapriya, Garbhabhaksa, and Maṁsapriya further evoke an aura of mystique and power. These Yoginis embody the Pancha Makara elements of wine, fish, and flesh in their rituals.

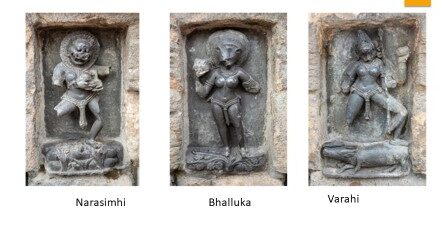

(Figure 15: Yoginis with theomorphic features)

Many statues of Yoginis showcase features that resemble animals like monkeys, lions, serpents, bears, and elephants (theomorphic). Figures include Narsimhi, Ostagriva, Varahi, Sarpassa, Ganesi, Bhalluka, and Vikatanaina. These distinct animal characteristics highlight the Yoginis’ ability to transform into an animal or bird. They represent the Yoginis’ prowess in fighting off malevolent forces, and their unparalleled powers which distinguish them from humans and raise them to a divine level.

Saraswati

(Figure 16: Yogini represented as Saraswati)

In Hirapur, there exists a distinctive group of Yoginis. Initially, these figures were secondary characters in myths, serving as partners, subsidiary deities, or individuals under possession. However, within the Yogini tradition, they transition into dominant, independent deities. Consider the Yogini Sarasvati as an example: although she embodies a female form and clutches a veena, she unexpectedly features a moustache, which she is seen twirling. This image amalgamates both male and female characteristics, showcasing the union of these two elements in a Yogini. Such depictions are rare and not typically seen in other Yogini temples or statues.

Rati

(Figure 17: Yogini represented as Rati)

Typically, Yoginis lack male counterparts, yet this one is not only a renowned mythological wife but is also showcased alongside her husband Kamdev in the temple. Contrary to Rati’s symbolic nature, this Yogini is depicted in dominance, standing atop and even seemingly suppressing her husband.

It is conceivable that this portrayal showcases the Yogini overpowering the prideful Kamadeva. However, the representation here is more about a woman’s overwhelming and uncontrolled passion. Despite being known as a renowned wife or consort, Rati or the Yogini in this context transcends her traditional role. She adopts a powerful and fierce persona, challenging and redefining conventional gender norms.

Maithuna, a key component of the Panchamakara, is integral to the tantric yogini ritual. Within the Yogini chakra, every male is seen as Bhairava and every female as Bhairavi. However, no Maithuna carvings are present in the Hirapur temple, nor is there any representation on the base. The Kularnava Tantra mentions the sexual aspects of Yogini worship, suggesting that the sixty-four Yoginis should be depicted in intimate union with sixty-four Bhairavas for proper worship. As per Vidya Dehejia, tantric scriptures emphasize such portrayals, asserting that without these detailed representations, worship is ineffective. During Maithuna rites, varna and jati differences dissolve, with all women embodying Devi and all men representing Shiva. While other aspects of the Panchmakaras might have been practised in the temple, Maithuna rites likely took place privately in homes.

Every Yogini in a circle is to be worshipped separately for each one has a different siddhi to confer. We realize that Yoginis are nothing but the manifestation of one divine unmanifested principle in the Chandi Mandap. Circumambulating and worshipping the Yoginis slowly but steadily stabilizes the devotees’ minds in the Sukshma aspect of Parabrahman,

After worshipping the Yogini circle devotee come to the centre or the Bindu of the circle called Chandi Mandap which is akin to Garbhagriha.

The Chandi Mandap

(Figure 18: Chandi Mandapa)

(Figure 19: Central Chandi Mandapa Bhairavas)

At the centre of the circular temple stands a roofless square Chandi Mandap. It has entrances on all four sides with two niches provided on either side of each entrance, resulting in eight niches in total.

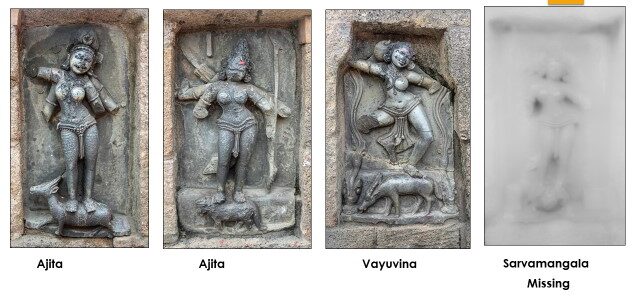

Four Yoginis, Sarvamangala, Ajita, Surya Putri, and Vayu Veena are placed on Chandi Mandap of which only three are there, Yogini Sarvamangala is missing. Each Yogini in the Chandi Mandap is juxtaposed with Bhairava. Symbolizing Bhairava as Shiva and Yogini as Shakti.

Bhairava, a significant figure in Shaiva Tantrism, is closely associated with the Yogini worship, as seen from his statues in Yogini temples. This fierce manifestation of Shiva is considered the leader of the Yoginis. The name “Bhairava” is derived from “Bhay” (fear) and “rava” (sound), representing the fearsome. In these temples, Bhairavas serve as both protectors and supporters, often placed at cardinal points as vigilant guardians of the sacred space. Their imposing presence is thought to ward off evil forces. While their depictions vary from threatening to benevolent, they always emanate strength and protection. Within the Yogini temple context, Bhairavas are not just guardians but also powerful spiritual allies of the Yoginis, enhancing the temple’s sacredness.

There are four Bhairavas in four niches sitting in Lalitasana, except Ekapada Bhairava who stands on one foot. Bhairavas are portrayed as serene and smiling rather than in intimidating forms and are with Urdhava Linga or upright phalluses. They have a halo and are adorned with ornaments associated with Shiva and holding Shiva’s symbols such as Akshmala, Damru, Khadaga, a skull cup, and a Trishul. All the Bhairava panels have flying Gandharavs playing music and dancing carved on the topmost part of niches. Gandharvas are celestial beings symbolizing that Chandi Mandap is a celestial region where the Ultimate Reality resides. At the bottom of the panel, we find Yoginis drunk on wine or blood and dancing in rapture. Rapture is a state of ecstasy or pure joy again a representation of the Celestial world.

Bhairavas are sitting in lalitasasan on padmasana. The lotus emerging from the navel of the Shava or the corpse forms the Padmasana on which the Bhairavas are seated. The Shavasadhana in tantric tradition is where the rituals are performed sitting on the corpse and this infuses the life in the shava and the shava then becomes Shiva.

The Sanskrit words: “Urdhva’’ means “upward linga.” The upward position of the linga represents the ascendant energy of the transcendental reality, the ascendant path of the Kundalini energy, the evolutionary force in humans, which ascends upwards, symbolizing spiritual progress. It is at this place where a devotee transcends from Human Consciousness to Divine Consciousness.

The presiding deity, in the centre of the Chandi Mandap, is missing and different versions believe the missing deity could have been Shiva as Nataraj, Shiva as Martand Bhairava, or Moha Bhairava. Since the Chandi Pitha remains unoccupied, with all worshipping activities taking place in the presence of Yogini no.31, Mahamaya is considered the principal deity of the temple and the temple is also called Mahamaya temple.

Chandi Mandap is the Bindu or the Garbhagriha where the Ultimate Reality resides. Bindu symbolizes the absolute and the timeless principle beyond repetition and relativity and is intended as a reminder of the ultimate goal of the journey that a devotee undertakes.

Four Bhairavas and four Yoginis form the most intimate chakra around the central deity. Bindu is protected by the Bhairavas who act as Dwarpalas and do not allow the unworthy to be in the presence of the Ultimate Reality. Only the ones who have gone through the mental and physical transmutation from Sukshma by worshipping all the Yoginis in various circles are allowed in its presence.

The presence of Bhairava and Yoginis shows that this region is a celestial region where Shiva resides. Slowly but steadily, the devotee’s mind is levitated from Sukhsma to the Para aspect of the Parabrahman.

The universe is the manifestation of God’s divine form in the world of mundane existence. The body of the temple represents that cosmic form, whereas the presiding deity is the manifestation of the transcendental form of God descending from beyond the mundane. A Chausath Yogini temple at Hirapur functions as a place of transcendence through its art and architecture. A place where a devotee progresses from the world of illusions to the world of knowledge and Ultimate truth.

References

Behera, Monalisa. 2018. Mothers, Lovers & Others: A study of Chausathi Yogini temple in Hirapur

Brighenti, Francesco. 1997. Sakti Cult in Orissa, Ph.D. thesis, Utkal University, Bhubaneshwar

Dehejia, V. 1986. Yogini Cult and Temples: A Tantric Tradition. New Delhi: National Museum.

Gadon, Elinor. ‘Probing the Mysteries of the Hirapur Yoginis’. In ReVision Vol. 25, no. 1 (2002): 33-41.

Mahapatra, K. N. ‘A Note on the Hypaethral Temple of Sixty-four Yoginis at Hirapur’, in Orissa Historical Research Journal II (1953)

Roy, Anamika. 2015. Sixty-Four Yoginis: Cult, Icons and Goddesses. New Delhi: Primus Books.

Photos Courtesy:

Kevin Standage photography, Sahapedia, Collecting moments

Feature Image Credit: wikipedia.org

Conference on Tantra & Tantric Traditions

Watch video presentation of the above paper here:

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.