Introduction

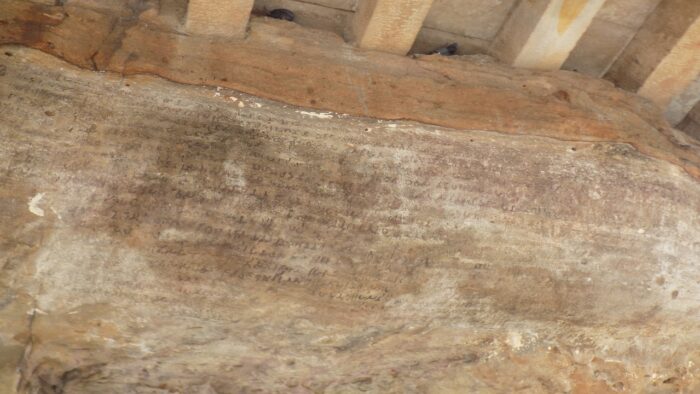

The state of Odisha in Eastern India can certainly pride itself on its rich and variegated past. From lofty Hindu temples to the somber Buddhist remains, the state of Odisha has everything which a history and heritage enthusiast would dream to come across. The land which today is known as Odisha was known in the ancient times as Kaliṅga. It has been frequently mentioned in the Itihāsas, Purāṇas as well as epigraphical sources. When we think of the word ̍Kaliṅga ̍, the sight of the mighty Mauryan forces of Emperor Aśoka marauding this land comes to our minds. The battle of Kaliṅga which is mentioned by Aśoka in one of his rock edicts is an important landmark in the history of India as well as Odisha. We have no definite idea about who ruled Kaliṅga during the time of Aśoka or any other details about the political history of this region during and preceding the Mauryan rule. That this region formed a part of the Mauryan Empire is evident from the Aśokan edicts which have been engraved on rocks at Dhauli and Jaugada. However, in the history of Kaliṅga belonging to the post Mauryan period, we find a luminous star called Khāravela who ruled over a kingdom whose limits transcended the frontiers of Kaliṅga. The exploits of Khāravela are known from his Hāthigumphā Inscription. Hāthigumphā is a cave which is a part of the Udayagiri cluster of caves on the outskirts of Bhubaneswar, the capital of Odisha. The Udayagiri Caves along with the adjacent Khaṇḍagiri Caves are groups of Jaina Caves which were in all probability patronized by Khāravela himself. The inscription was first noticed by one Stirling in 1825 and it was first published in 1837 by James Prinsep based on an eye copy prepared by Kittoe. The first reliable reading of this inscription was done by Bhagwanlal Indraji in 1885. This inscription was further edited by epigraphists like George Buhler, T. Bloch, Kilehorn, J.F. Fleet, K.P. Jayaswal and R.D. Banerji. The language of the inscription is Prākrit and the script is Brāhmī.

The Date of the Hāthigumphā Inscription

The date of the Hāthigumphā has confounded scholars since its discovery in the 19th century CE. The phrase ̍ ti vasa sata nandarāja ̍ has given rise to two major time frames for Khāravela. A few scholars interpreted this phrase as 103 years after the Nanda king whereas a few others understood this term as 300 years after the Nanda ruler. The last known date for the Nanda dynasty is 324 CE. So if we go by the first interpretation, we would have to place Khāravela around 221 BCE which does not agree with the accepted dates for the rulers that he mentions in the inscription. This inscription mentions kings like Sātakarṇi (who is identified with the early Sātavāhana ruler Sātakarṇi I), Demetrius and Bahasatimita. These kings flourished in the 1st century BCE. Latest research on the Hāthigumphā Inscription has taken the aid of palaeography or the analysis of the script used for inscribing the inscription. Palaeographically this inscription has been dated to the 1st century BCE (Chakravarti 2016). On the basis of architecture and sculpture, the Udayagiri and Khandagiri Caves can be dated to the same period.

Personal details of the King

The inscription opens with the veneration of the Arhats i.e. Jinas and the Siddhas, thus indicating that king Khāravela was a Jaina. Khāravela calls himself as an Aira or Aila and a descendant of the great Mahāmeghavāhana. The term Airena is used as an honorific for Khāravela and which in the opinion of Dr. Shashi Kant stands for Āryeṇa which is indicative of a person who was of high birth and noble descent. As per this scholar, it does not allude to the mythical character named Iḷa or Iḷā (Kant, 1971: 45). He further comments that ̍Mahāmeghavāhana ̍, a title also borne by other rulers of Kaliṅga is synonymous with Indra, whose mount is an elephant. The reason underlying such a title, as suggested by Dr. Shashi Kant may have been the great number of elephants found in the land of Kaliṅga (Kant, 1971: 45). Khāravela also hailed from the dynasty of the Cedis and was the ruler who brought glory to the Cedi dynasty. The Cedi dynasty has been frequently mentioned in texts like the Mahābhārata and Purāṇas and the most famous, rather infamous ruler of this dynasty was Śiśupāla who was a sworn opponent of Kṛṣṇa. There is an urban early historic site called Śiśupālagarh on the outskirts of Bhubaneswar and some scholars identify this site as being the capital of the erstwhile kingdom of Kaliṅga. Veteran archaeologists like B.B. Lal, Prof. R.K. Mohanty and Prof. Monica Smith have conducted in depth scientific excavations at this site and have arrived at some very insightful results. Khāravela was endowed with auspicious marks which highlighted his greatness. Khāravela calls himself the overlord of Kaliṅga. For the initial fifteen years of his life, he engaged himself in various kinds of sports. He was trained in and he mastered the requisite branches of knowledge for a king like royal correspondence, currency, finance, civil and religious law. For the next nine years he was appointed as the Yuvarāja or heir apparent and at the age twenty four he was coronated as the king. The inscription declares that Khāravela was destined to have many conquests just like the legendary Vena. Khāravela was himself proficient in the science of the Gandharvas i.e. music. As per epigraphical evidence, Khāravela definitely had two queens and one of them i.e. Vajiraghara gave birth to a child in the 7th regnal year of Khāravela. The other queen was Sindhulā and perhaps she was the same queen who has been mentioned as the Agamahiṣī in the Svargapuri Cave Inscription. Khāravela does not provide the name of his issue from Vajiraghara but in the opinion of Dr. Shashi Kant he could be probably identified with Ārya Mahārāja Kaliṅgādhipati Mahāmeghavāhana Śrī Kūdepa whose inscription is found in the adjoining Mañcapuri Cave (Kant, 1971: 46). In the same cave we also find an inscription of Kumāra Vaḍukha, who as opined by Dr. Shashi Kant could be the same as Kūdepa (Kant, 1971: 46). Khāravela was endowed with exemplary virtues. He respected every faith and was the repairer of all kinds of temples. He was a great warrior whose chariot and army were indefatigable and with his prowess he himself defended and protected his kingdom.

Public Works of Khāravela

Khāravela inaugurated many public reforms immediately after assuming kingship. In his very first regnal year he carried out repairs for the gates, walls and buildings of the city which had been destroyed by a storm. The city where he initiated these construction activities could have been the city of Kaliṅganagara. In the same city he constructed embankments of a lake named after a sage called Khibira. He also repaired other tanks and cisterns as well as restored gardens at a cost of thirty five hundred thousand (the specific name of the currency is not mentioned). In the capital city, he arranged for the display of dapa, dancing, singing and playing of various instruments as well as festivities and assemblies. Dapa in modern Sindh is used in the sense of a village performance where men move on cutting antics. Drava is the Sanskrit term which implies a dance and is associated with the act of motion or running. In his fifth regnal year, Khāravela brought into the capital from the road of Tanasuliya a canal dug up three hundred years after the Nanda Rāja. He is also said to have performed the Rājasūya Yajña and remitted all the tithes and cesses. He also presented the administrative bodies like the City Corporation and Realm Corporation with many privileges. He also gave wish fulfilling trees, elephants, chariots with their drivers, houses, residences and rest houses. To make all these acceptable, he granted exemptions from taxes to the Brāhmaṇas. After a sequence of victorious conquests, he had the Mahāvijam Pāsāda or the Palace of Great Victory constructed at a cost of thirty – eight hundred thousand. He built towers with carved interiors and created a settlement of a hundred masons and gave them an exemption from land revenue. He also had a stockade for elephants constructed.

Conquests of Khāravela

Khārevela ̍s first conquest was in the western direction when he sent his caturaṅga army comprising of cavalry, infantry, elephants and chariots not caring for the Sātavāhana ruler Sātakarṇi I. According to K.P. Jayaswal, the Sātakarṇi referred to in the inscription is Sātakarṇi, the husband of Queen Nāganikā and the third ruler of the Satavāhana dynasty. Khāravela ̍s forces reached the river Kañha Beṁṇa and threw the city of Musikanagara in a state of shock with his attack. The river Kañha Beṁṇa was earlier identified with the river Kṛṣṇā. Later research suggests that this river should be identified with the river Wainagaṅgā in eastern Maharashtra. The town of Musikanagara is identified with a town on the River Musi near the fortress of Golconda in the state of Telangana. Khāravela also subdued the Raṭhikas and Bhojakas and made them bow at his feet. The Raṭhikas and Bhojakas have been identified with the Mahāraṭhis and Mahābhojas who have been mentioned in the inscriptions of the Sātavāhanas as well as in the inscriptions from Buddhist rock-cut cave sites like Kanheri, Kuda and Bedsa in Maharashtra. The Raṭhikas are the same people who have been mentioned in the Aśokan inscriptions at Girnar, Dhauli, Shahabazgarhi and Manshera. Bhojakas have been also referred to in the Aśokan inscriptions at Shahabzagarhi, Manshera and Kalsi. The Raṭhikas and Bhojakas could have been local ruling families, especially in the Deccan and their overlords must have been the Sātavāhanas. In his eighth regnal year, Khāravela deployed his forces to sack Goraṭhagiri. Goraṭhagiri is generally identified with the Barabar Hills to the south of Pāṭaliputra in Bihar though the evidence from inscriptions indicates that the ancient name of the Barabar Hills was Khalatika. By the strength of his armed forces, Khāravela also put pressure on Rājagṛha, the old capital of the state of Magadha. Khāravela was so powerful that he made the Yavana ruler Dimita retreat to Mathurā with his demotivated army. Dimita is identified with the Greek king Demetrius. In his tenth regnal year he applied the three fold policy of chastisement, alliance and conciliation and sent out his army to defeat the kings of Bhāratavarṣa. This is the first epigraphical reference to the term ̍ Bhāratavarṣa ̍. Here Bhāratavarṣa, in all probability implies northern India. He is said to have procured jewels and other precious objects from the kings of Bhāratavarṣa whom he subjugated. He then turned his attention to the south and attacked the market town of Pithuṃda which had been founded by the Ava king. Here, Khāravela had the land ploughed by asses thus indicating that he completely destroyed the town. The tentative identification of Pithuṃda is with the town of Pitindra which has been referred to by Ptolemy. This city might have been located somewhere on the Coromandal Coast and might have served as the capital of Ava or Avarni. He was also successful in breaking the confederacy of the Tramira or Southern Kings which could have posed a potential threat to his own Janapada. The word Tramira implies Dramira or Tamila kings. The Colas, Pāṇḍyas, Satiyaputras and Tāmraparṇiyas have been mentioned by Aśoka in his rock edicts and they must have constituted a formidable confederacy which may have checked the expansion of the Mauryan Empire in the far south and beyond. That Aśoka ruled over a considerable part of Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka is attested by the presence of his rock edicts in both these regions. Perhaps the strongest among these Tamila kings were the Pāṇḍyas. In his twelfth regnal year, Khāravela again turned his attention to northern India which has been referred to as Uttarāpatha. This time his target was the kingdom of Magadha and Khāravela easily subdued the Magadhan forces by making his elephants enter the Sugaṁgīya Palace and made the king of Magadha, Bahasatimita to bow at his feet. Coins of a king named Bahasatimita have been discovered at Kosam, the site of ancient Kauśāmbī and there is a possibility that he may be the same king as mentioned by Khāravela. The political domain of Bahasatimita may have extended up to Kauśāmbī. He also retrieved an image of Kaliṅga Jina which had been previously taken to Magadha by a Nanda king. Kaliṅga Jina is perhaps a reference to an image of Sītalanātha, the tenth Tirthankara. Khāravela is also said to have brought back many treasures from Aṅga and Magadha. Khāravela also defeated the Pāṇḍya king and took away elephants, horses, jewels, rubies and pearls in hundreds from him. From the descriptions given in the present inscription, the conquests of Khāravela seemed to be directed towards procuring material wealth rather than an expansion of his kingdom. This inscription also helps us in understanding the political situation of India in the 1st century BCE and the names of a few contemporary rulers of Khāravela. The inscription is also a pointer towards understanding the military history of Ancient India. Not only were the four wings of the army- infantry, cavalry, elephants and chariots fully developed, this inscription also carries a reference to the naval force of Khāravela. One point worth taking note of is that Khāravela mentions a Nanda king but makes no mention of Emperor Aśoka who led a major campaign against Kaliṅga in the 3rd century BCE. We may surmise that Aśoka was not the first Magadhan ruler to have attacked Kaliṅga and going by the references in the present inscription, a king from the Nanda dynasty had already made inroads into the Kaliṅgan territory and had even taken away an image of a Tirthankara from there. However the reference to Kaliṅga remaining ̍avijita ̍ or unconquered till the 7th regnal year in the 13th Rock Edict of Aśoka does not reaffirm this conjecture. We may add here that the Nanda conquest may not have engendered significant political ramifications and may not have been directed towards territorial gains. Kaliṅga in all probability asserted its independence after the death of Aśoka when the Mauryan state slipped into a state of decline. Khāravela and his predecessors (whom he does not name) were completely independent rulers with a strong military backing.

Khāravela and Jainism

In Khāravela ̍s thirteenth regnal year when the Wheel of Conquest had revolved i.e. when the religion of the Jina had been preached, he made various gifts to the Jaina monks and ascetics like royal maintenances, China clothes i.e. silks and white clothes. These gifts were made at the Kumārī Hills. We may propose another albeit slightly divergent view regarding the Wheel of Conquest. Jainism, like Sanātana Dharma and Buddhism contains, the idea of a Cakravarti. As per the Jaina texts, the current age has twelve Cakravartis and these Cakravartis are sovereign rulers. The Wheel of Conquest could be related to Khāravela considering himself as a Cakravarti who led victorious conquests against his powerful contemporary kings. The concept of a Dharma Cakra is also present in Jainism. The Dharma Cakra, radiant like the sun and containing a thousand spokes, is said to always move in front of a Tirthankara.

Khāravela also offered these gifts to the preachers on the religious life and behavior at the Relic Memorial. The Kumārī Hills are in all probability the Udayagiri Caves. The Relic Memorial could refer to symbolic graves constructed by the Jainas which were known as Niśīdī or Niśīdhī. As per the references in the inscription, Khāravela is also supposed to have convened a council of the Jaina monks who have performed noble deeds from all quarters. This council had two objectives- one was to settle the disputes between the Śvetāmbara and Digamabara sects of Jainism and the other was to compile the sevenfold Aṅgas which could be a reference to Jaina Canonical Literature which in actuality comprises of twelve Aṅgas. This assembly of monks must have put together the scattered or lost texts of the Jaina religion. He also built a relic depository for the Arhat on top of the Udayagiri hill with high quality stones brought from distant mines. We cannot say with exactitude about the identity of this Arhat. He also had dwellings excavated on the same hill for the monks. In the inscription there is a reference to an image of Kaliṅga Jina and this is indeed a very noteworthy one. As far as archaeological evidences are concerned, we do not find images of deities in the pre-Mauryan period. However, the allusion to the Kaliṅga Jina testifies to the fact that there were icons which were worshipped in the pre-Mauryan times as well. This reference is a clear pointer towards the antiquity of image worship as well as the prevalence of this practice in Jainism. This image may have been of wood or metal and seems to have been a portable one. The worship of the Kaliṅga Jina during the Nanda regime also sheds valuable light on the spread of Jainism in Odisha. This reference establishes beyond doubt that Jainism was an active faith in the Kaliṅga region in the pre-Mauryan times and that the Jaina Saṅgha must have played a key role in the dissemination of Jainism beyond its core regions of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh.

Concluding Remarks

The Hāthigumphā Inscription is the primary source which provides details about the illustrious Khāravela and his brilliant career. The pages of history are otherwise silent about this highly able ruler. He was well trained in statecraft and was committed to the welfare of his people and he carried out a number of reforms for the well being of his subjects. He belonged to the Cedi or the Mahāmeghavāhana dynasty of Kaliṅga. The rise of this dynasty attests to the fact that in spite the violent inclusion of Kaliṅga into the Mauryan Empire, this state asserted its independence most probably under the leadership of an ancestor of Khāravela in the late 2nd or early 1st century BCE. The Mauryas had laboured to incorporate the bountiful and prosperous region of Kaliṅga within their empire and the relations between these two states were tense since the Nanda regime. Khāravela himself led a campaign against Magadha and subjugated its ruler. Khāravela ̍s inscription is also an important source to know about the political history of India in the 1st century BCE as well as the state of the military forces. There are references to large amounts of money in the inscription and these indicate that there must have been some kind of coinage which was issued by Khāravela and his ancestors. Khāravela patronised Jainism though he even took care of the Brāhmaṇas in his dominion. Though he himself was a devout Jaina, he did not hesitate to conduct war campaigns against his rival forces and inflict crushing defeats on them. Going by the descriptions in the inscription, these campaigns proved to be more economically beneficial than securing political gains. These war expeditions might have been mainly aimed at striking terror in his contemporary rulers who might have been potential threats to his kingdom than to extend its limits. The economic condition of Khāravela ̍s state must have been fairly stable because the inscription records instances when the king remitted taxes. Similarly only an affluent economy could have supported the large scale public works that Khāravela implemented.

A few other points also require consideration here. Though Khāravela himself professed Jainism, he had performed the Rājasūya Yajña which was a very significant yajña in the Vaidika culture. This was a yajña which was performed by Kṣatriyas and symbolized the political sovereignty and hegemony of the ruling class over its territory and subjects. Here we find a mixed religious identity of Khāravela. Though a practicing Jaina, as a king, Khāravela may have deemed it imperative to perform the Rājasūya Yajña to assert his political strength and independence. Performing this sacrifice may have been more as a symbol of his Rājadharma as the king of the land though his own personal faith i.e. Jainism was certainly not favourably disposed towards the Vaidika culture centering round yajñas. Vaidika culture was not totally rejected by the followers of the heterodox sects in actual practice. He also showered favours on the Brāhmaṇas, a policy which was adopted by Aśoka as well. His identity as a Jaina worshipper was not exclusive and Khāravela might have had to reorient it in accordance with the political, social and cultural conditions of his time. In addition, he freely sought parallels with Vaidika figures like Vena with his own self. These characters from the Vaidika culture had deeply percolated into the Indic culture and were beyond sectarian differences. Further, the differences between the various religious communities at that time might not have been so acute and pronounced as we find in our own times. As religious systems of Indic origin, the Vaidika and Avaidika Darśanas certainly exhibited certain common cultural traits, at least in the initial stages of their evolution. The entire issue of Khāravela ̍s mixed religious identity is still an open ended question.

References

- Barua, B.M. 1938. “The Hathigumpha Inscription of Kharavela.” The Indian Historical Quarterly, Volume XIV: 459-485.

- Chakravarti Ranabir. 2016 (3rd Edition). Exploring Early India: Up to C. AD 1300. Delhi: Primus Books.

- Jayaswal K.P. and Banerji R.D. 1929-30 (Reprint 1983). “The Hathigumpha Inscription of Kharavela.” Epigraphia Indica, Volume XX: 71-89.

- Kant, Shashi. 1971. The Hathigumpha Inscription of Kharavela and the Bhabru Edict of Asoka- A Critical Study. Delhi: Prints India.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.