The Yogic Tradition

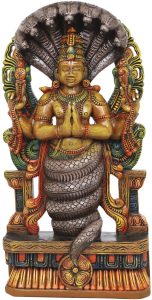

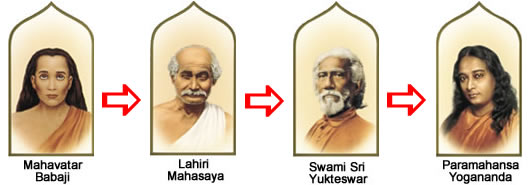

The tradition of Yoga and Yogis in India is an ancient one whose defining precepts were enunciated by Patanjali in his Ashtanga Sutra. The specific lineage in which Paramahansa Yogananda was initiated into, was the lineage of the mythical and ‘deathless’ Yogi Mahavatar Babaji who is said to have retained his body for hundreds of years who it is claimed, initiated Shyamacharan Lahiri, better known in Kriya Yoga circles as Lahiri Mahasaya, into the technique of Kriya Yoga. Yogananda in his Autobiography of a Yogi claims that Babaji had initiated Adi Shankaracharya and Kabir into Kriya Yoga but the actual technique which, in the tradition, is believed to be originally taught by Sri Krishna himself, was lost in the medieval ages until in 1861 he is said to have initiated Shyamacharan Lahiri (1828-1895) better known as Lahiri Mahasaya and thus revived Kriya Yoga for the modern age.

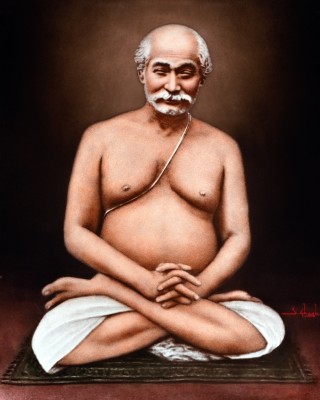

Lahiri, who was an accountant in the Military Engineering Department of the British government at Banaras (now Varanasi), was instrumental in initiating hundreds of disciples into Kriya Yoga and many spiritual seekers come to him from distant parts of India. Among his more famous Yogi disciples was Swami Bhaskarananda Saraswati of Banaras, Balananda Brahmachari of Deoghar, Swami Pranabananda, Panchanan Bhattacharya, Sri Yukteswar Giri, Bhupendra Nath Sanyal, etc. Regarding the work of Lahiri Mahasaya in popularizing the spiritual practice of Yoga especially among householders, Yogananda says, “Unknown to society in general, a great spiritual renaissance started in 1861 in a remote corner of Banaras.” We are told that due to the efforts of Lahiri Mahasaya, Bengal became honeycombed with small Kriya groups at the time, particularly in the areas of Krishnanagar and Bishnupur. His disciple Panchanan Bhattacharya had opened a press in Kolkata called the Arya Mission Institute which published a popular edition of the Bhagavad Geeta in Bengali.

It was another disciple originally named Priyanath Karar who later took the vows of a sannyasi after the death of his wife and daughter and was thereafter known as Sri Yukteswar Giri (1855-1936), who was to be Yogananda’s Guru and not only initiate him into the technique but also shape his world-view to a significant extent and send him to the West for the mission of popularizing the practice of Yoga.

Colonialism and the Indian Response

In the nineteenth century, the introduction of English education in India had resulted in the creation of a section of English-educated Indians who were alienated from the traditional religious and cultural outlook of the country and came to imbibe a Western world-view. This led to the creation of an inferiority complex regarding the indigenous Indic tradition and particularly Hindu beliefs and practices. There was also another section of intellectuals and thinkers starting from Rammohun Roy (1772-1833) onwards who believed in openness in accepting the best of Western thought and scientific education while at the same time attempting to reform Hindu religion and society in tune with the new sensibilities. In the field of religion, there were some early attempts to study and incorporate some of the elements of the Christian tradition which seemed attractive to these individuals while retaining the Hindu religion or at least what they considered a ‘reformed’ version of the Hindu tradition. Thus Rammohun Roy wrote his The Precepts of Jesus in 1820 and another very influential leader of the Brahmo Samaj, Keshub Chandra Sen (1838-1894) incorporated Christian elements into his eclectic sect called Nava Bidhan or the New Dispensation and had delivered a famous lecture entitled Jesus Christ, Asia, and Europe in 1866. These were to be forerunners of the later synthesis attempted by Yogananda and his Guru Sri Yukteswar Giri.

The feeling of inferiority on the part of Hindu religion and traditions which some- other leading Brahmos in the middle of the nineteenth century like Debendranath Tagore, Raj Narayan Bose, etc. tried to counter, was finally checked by figures like Ramakrishna Paramahansa and his most famous disciple Swami Vivekananda who together ended up affirming the validity of the Hindu religious and philosophical tradition. Swami Vivekananda was also a pioneer in attracting a following in the West due to his speeches in the World Parliament of Religions at Chicago in 1893 and his lecture-tours in the USA, UK, and other countries of the West. He also established Vedanta Societies in many parts of the West and tried to set in motion a process of building up an organization for spreading Indian philosophical thought particularly Vedanta in the West. This was also to be a template that Yogananda would draw on for his mission to the West.

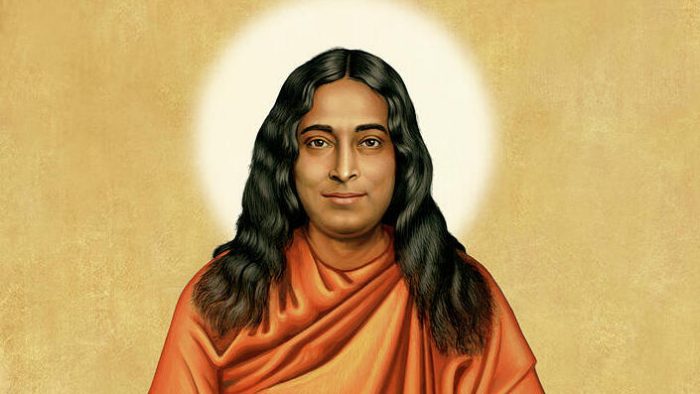

Paramahansa Yogananda: Yoga for the Modern World

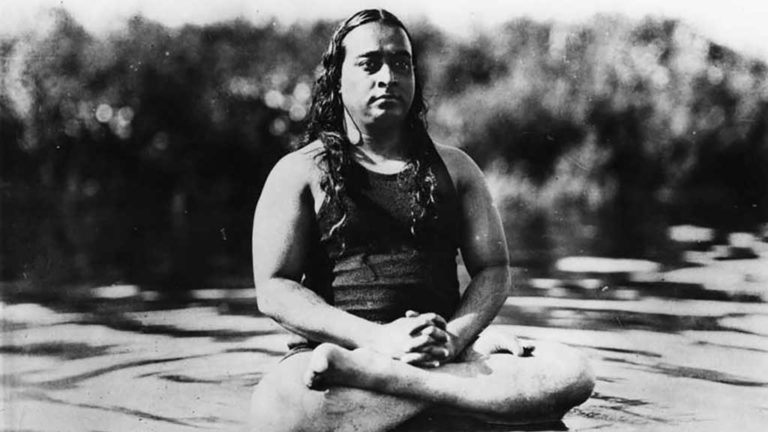

Mukunda was born to Bhagabati Charan Ghosh (1853-1942) and Gyana Prabha Ghosh (1868-1904) on January 5, 1893, when his parents were stationed at Gorakhpur. His father was a self-made man who had struggled in abject poverty in his youth and was subsequently employed in the office of the Government Examiner of Railway Accounts. Both his parents have initiated disciples of Lahiri Mahasaya and consequently, their eight children were brought up in an atmosphere of spirituality and religiosity at home. Their mother narrated stories from the Ramayana and Mahabharata for the children and also made an earthen image of the Goddess Kali for young Mukunda. It is said that Lahiri Mahasaya had predicted that the boy would be a Yogi and would “carry many souls to God’s kingdom”3 both before his birth and also when he had blessed him as an infant. Mukunda’s mother passed away from cholera when he was but eleven years old and this tragedy had a great effect on him and accentuated his spiritual search for the Divine Mother. The young boy Mukunda was attracted to sadhus, temples, and spirituality from his very childhood rather than his studies or any other worldly matter. An unsuccessful attempt to escape to the Himalayas in search of Yogis and God-realization along with two other boys made clear to his family that normal family life was not for Mukunda. After completing secondary school, he joined a Banaras hermitage named Bharat Dharma Mahamandal However, life at the hermitage did not give him the spiritual dividend he was seeking and while living there he met Sri Yukteswar Giri, a dramatic meeting that was to shape his future life and spiritual career. Giri had a hermitage at Srirampur, a little outside Kolkata and Mukunda thus returned to Kolkata where on the insistence of Sri Yukteswar, he enrolled for a college degree in Serampore College, run by the Welsh missionaries. It was while graduating that he was initiated as a sannyasi by Yukteswar with the name Swami Yogananda. During this time he spent a lot of his time at the hermitage and absorbed the teachings and spiritual wisdom of Yukteswar.

After completing his graduation in 1915 he spent the next five years establishing a boys’ school at Ranchi based on Yogic principles of spiritual education named the Yogoda Satsanga Brahmacharya Vidyalaya, a Sadhana Mandir at Kolkata and founded the Yogoda Satsanga in 1917. In 1920 he received an invitation to speak at the International Congress of Religious Liberals in Boston in the USA. There he delivered a lecture on “The Science of Religion” and receiving requests for further lectures, traveled cross-country drawing huge crowds at his lectures and speaking engagements. He soon established groups of followers in some major cities like New York, Philadelphia, Denver.

In 1920 he founded an international organization that was first known as Yogoda Satsanga Society of America and later in 1935 incorporated as the Self Realization Fellowship. In 1925 he founded the international headquarters of his organization at Mount Washington in Los Angeles. He soon gathered about him a band of dedicated American men and women who took the vows of sannyas from him and formed a nucleus of monks and nuns to shoulder the organizational responsibilities of the rapidly expanding work. The Self Realization Fellowship has today expanded to about five hundred centers in fifty-four countries across America, Europe, Latin America, Africa, and Asia. There are about one hundred and fifty centers in the USA alone.

Unlike Vivekananda who toured and lectured in the West but made India the main focus of his work, Yogananda spent the next two decades lecturing and building up his organization in the USA except for a single trip to India in 1935-36 during which his Guru Sri Yukteswar Giri passed away. In 1946 he wrote his bestseller Autobiography of a Yogi which is considered to be a spiritual classic and has been translated into thirty-eight languages including twenty-two Indian languages so far. Apart from the Autobiography he also wrote many other books including a two-volume commentary on the Bhagavad Gita1 in its Yogic interpretation. It is to be noted that at the time of Yogananda’s death in 1952, his organization in America alone had one hundred and fifty centers, a significant achievement for one who before sailing for the West was apprehensive since he had not lectured in English ever before and was filled with trepidation at the prospect.

This apparent success in negotiating an apparently hostile cultural terrain in America implied a level of maturity and cultural intelligence which was something new for a representative of the Yogic tradition at that time. His success in building up a band of Western close disciples who would in future take over the reins of the organization and shoulder the burden of carrying forward the Master’s legacy shows a level of “second culture acquisition” though without loss of the essential elements of the primary culture.

Innovations in the Yogic Tradition

Traditionally the Yogic knowledge was always passed on from Guru to Sishya, mostly orally though some other disciples of Lahiri Mahashay notably Panchanan Bhattacharya, etc had started the dissemination of printed literature and had started the Arya Mission Press for this purpose. Paramahamsa Yogananda was among the first to start a formal organization for the dissemination of Yogic knowledge and in this too perhaps, the template of Swami Vivekananda who had founded the Ramakrishna Mission in 1897 was in front of him. Like Vivekananda, he too had to face questions from traditionalists within the order to which he replied that “the organization was the hive and spirituality the honey”. He realized that to properly disseminate the “spiritual honey” among the “bees” that is, the spirituality-hungry souls in the modern globally-connected world, the building of a “hive” or organization was necessary along with modern techniques of reaching out, organizing lecture-tours, disseminating printed material, etc., all of which were innovations in the traditional Yogic world.

He also introduced the system of correspondence courses by which enrolled disciples would receive by post every month four lessons which were progressively numbered up to 182. In addition, those who received Kriya Yoga initiation (which was to be done in person, in accordance with the tradition) would receive the additional Kriya yoga lessons. In this way, he built up a body of disciples who would form the core group of the organization and continue it even after Paramahamsa Yogananda passed away.

Intertextuality of Yogic and Christian Traditions: A New Interpretation

The process of transformation of the Indian tradition that started with Rammohun Roy continued throughout the nineteenth century and later opened up the process of transformation in some spheres while strengthening the tradition in some other spheres. It is significant that Roy had broken the taboo against crossing the seas and went to England and died there, though he did not preach his religious ideas in the West. While in India, he had cultivated links with the Unitarian Church. By the time Vivekananda arrived in the USA, the West had some cultural contact with Indian spiritual ideas through the Theosophical Society led by Madame Blavatsky and later Annie Besant. When Vivekananda’s Raja Yoga was published in 1896 it was one of the first works in English on Yoga meant for a modernized readership, both Indian and Western. Both Vivekananda’s Vedanta Societies and the Theosophical Society had built up a foundation that helped Yogananda as there was tremendous curiosity about Indian religion and philosophy among sections of the thinking public.

Apart from being the first Indian spiritual teacher to settle in the United States and make the West the focus of his work, Yogananda was also unique in the sense that he tried to incorporate the icons and outward structure of Christianity into his teachings. Before him, in India, it was again the Brahmo Samaj which had tried to borrow a little of the outward form of the Christian Church, for example, their use of pews as in a Church building, use of devotional songs and sermons in the form of worship which was called upasana, etc. But it was Yogananda and before him in a limited form Sri Yukteswar Giri who tried to synthesize some Christian beliefs and doctrines with the Yogic tradition and the Indian spiritual worldview. It has been said that Serampore’s environment of Christianity influenced Sri Giri. He had attended the Christian Missionary College at Serampore and became interested in Jesus’ life and the Book of Revelation. His intellectual mind searched for parallels between the inner symbolic and mystical meaning of the Bible and the Indian religious tradition. Some of these insights including the suggestion that Jesus Christ visited India and spent some years there are available in his book, The Holy Science or Kaivalya Darshanam. Thus we see that it was Sri Yukteswar who was the first Guru in the Kriya Yoga parampara of Lahiri Mahasaya to come in contact with Christianity and try to find parallels between Christian teachings and the entirely indigenous Yogic tradition he had inherited from Lahiri. Though Sri Yukteswar never visited the West, in trying to interpret Christian beliefs and doctrines in the light of Yogic traditions he laid the foundations of Yogananda’s work in the West and the synthesizing of the different traditions. Outlining the different kinds of knowledge that he received at the feet of Yukteswar during Yogananda’s training in the Serampore hermitage, he says:

Master expounded the Christian Bible with beautiful clarity. It was from my Hindu guru, unknown to the roll call of Christian membership, that I learned to perceive the deathless essence of the Bible, and to understand the truth in Christ’s assertion – surely the most thrillingly intransigent ever uttered: “Heaven and earth shall pass away, but my words shall not pass away.”

However, Sri Yukteswar and later Yogananda’s interpretations of the Christian scriptures including Genesis, Revelation, etc. are far removed from the standard Christian interpretation or interpretations of the same. Again, reminiscing of his youthful Serampore days, Yogananda says:

“The Adam and Eve story is incomprehensible to me!” I observed with considerable heat one day in my early struggles with the allegory. “Why did God punish not only the guilty pair but also the innocent unborn generations?” Master was amused, more by my vehemence than by my ignorance. “Genesis is deeply symbolic, and cannot be grasped by a literal interpretation,” he explained. “Its ‘tree of life’ is the human body. The spinal cord is like an upturned tree, with man’s hair as its roots, and afferent and efferent nerves as branches. The tree of the nervous system bears many enjoyable fruits, or sensations of sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch. In these, a man may rightfully indulge; but he has forbidden the experience of sex, the ‘apple’ at the center of the body (‘in the midst of the garden’). “The ‘serpent’ represents the coiled-up spinal energy that stimulates the sex nerves. ‘Adam’ is the reason, and ‘Eve’ is feeling. When the emotion or Eve-consciousness in any human being is overpowered by the sex impulse, his reason or Adam also succumbs.

Here, the interpreted inner meaning as given by Sri Yukteswar was more in tune with the Yogic concept of chakras and kundalini rather than any Western interpretation of the Bible. Yogananda himself takes the intertextuality to a further level when he says:

From a reverent study of the Bible from an Oriental viewpoint, and from intuitional perception, I am convinced that John the Baptist was, in past lives, the guru of Christ. Numerous passages in the Bible imply that John and Jesus in their last incarnations were, respectively, Elijah and his disciple Elisha… The very end of the Old Testament is a prediction of the reincarnation of Elijah and Elisha: “Behold, I will send you Elijah the prophet before the coming of the great and dreadful day of the Lord.” Thus John (Elijah), sent “before the coming…of the Lord,” was born slightly earlier to serve as a herald for Christ. An angel appeared to Zacharias the father to testify that his coming son John would be none other than Elijah (Elias).

Elsewhere again, Yogananda says, “Understanding of the law of karma and of its corollary, reincarnation… is displayed in numerous Biblical passages;…” Therefore, though Yogananda harmonized his teachings with Christian beliefs, the core beliefs of the Hindu tradition, that of karma and reincarnation were the core of his teachings also. Again, the core psycho-physical doctrine of the Yogic system, that of the seven chakras and the ascension of the kundalini force through the chakras, was again the fundamental basis of his interpretation of the Christian scriptures and also other religious texts of very different traditions.

Yogananda also wrote a Yogic interpretation of the eleventh century Persian Sufi mystic Omar Khayyam’s Rubaiyat, published under the title Wine of the Mystic1, in which he interestingly, interprets the Sufi verses in line with the Yogic tenet of the chakras and kundalini, none of which are part of any standard Islamic doctrine.

Cross-Cultural Partnerships in Yogananda’s Vision of Globalisation

Apart from such scriptural harmonizing, the outward structure of the SRF incorporated certain elements of a Christian church, as the SRF also refers to itself as a Church. Jesus was incorporated into the pantheon of Gurus as one of the six Gurus which start from Shri Krishna and then go on to Jesus Christ, Babaji Mahavatar, Lahiri Mahasaya, Sri Yukteswar and end with Yogananda himself, according to the given order.

Again, this was an innovation, for, in the original tradition of Lahiri Mahasaya, there is no such fixed pantheon of Gurus, and rather the other branches of the tradition (apart from the YSS/SRF line) follow the general Hindu tradition of honoring an evolving line of Gurus which is not fixed for perpetuity. But since Yogananda did not ordain anyone as Guru after him, the YSS/SRF follows the system of initiating new recruits as disciples of Yogananda himself, who is believed to perform the traditional function of the Guru even for the current recruits, though he is no longer in the flesh. Today, the Kriya Yoga initiation in the YSS and SRF organizations is still done in the name of Yogananda, i.e. he is the Guru to all initiates. After Yogananda, his American disciple who was also a very successful businessman, James J. Lynn, known in the order as Rajarsi Janakananda, succeeded him as President of the twin orders though not as Guru. He passed away in 1955, three years after being ordained as President as was succeeded by Daya Mata (Faye Wright) an American who was also one of Yogananda’s close disciples. She led the order till 2010, when she passed away at the age of 95 and was succeeded by Mrinalini Mata, and then by Swami Chidananda, the current President.1 In this way, all his successors, Rajarshi Janakananda, Sri Daya Mata, Sri Mrinalini Mata, and currently Swami Chidananda, were Presidents of the twin organizations but not Gurus, and it is the organization which handles the activities as well as arrangements for Kriya Yoga diksha. In the process, there has been a change in emphasis from individual Gurus as is the traditional norm, to the organization. This was definitely innovation and not the general tradition in India, though some have found some parallels in the Sikh tradition of ten Gurus being succeeded by the Adi Granth as the eternal Guru.

In the West, he formed successful cross-cultural partnerships with people such as Luther Burbank, renowned for his experiments of plant life and consciousness, W.Y. Evans-Wentz, the author of Tibetan Yoga and Secret Doctrines who also wrote a forward to Yogananda’s Autobiography of a Yogi.

It is significant that today the “Aims and Ideals of Yogoda Satsanga Society of India” include, “To reveal the complete harmony and basic oneness of original Yoga as taught by Bhagavan Krishna and original Christianity as taught by Jesus Christ, and to show that these principles of truth are the common scientific foundation of all true religions.” Others stated “Aims and Ideals” include, “To advocate cultural and spiritual understanding between East and West, and the exchange of their finest distinctive features,” and also, “To unite science and religion through realization of the unity of their underlying principles.”

Conclusion

The impact of colonialism and Western education in India provides a crucial perspective for the unraveling of the multiple strands in the transformation of indigenous tradition in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In the life and work of Paramahansa Yogananda we find interesting attempts at synthesis in the form of liberal borrowings from not only Christian but from spiritual traditions across the world including Persian Sufi traditions though they are incorporated within his works and teachings in a form that would be compatible with Yogic traditions, beliefs, and practices.

However, as I have shown elsewhere, the interpretation of Jesus Christ and the interpretation of his teachings are completely in line with the traditional Indic/Yogic teachings and worldview and there was no element of innovation in this regard. Yogananda, in fact, undermines the position of the Christian Church when he argues that Christ had preached the doctrine of reincarnation and the Yogic chakras all of which were subsequently distorted by the early Roman Church and following that, by the contemporary Christian denominations. He also attacks doctrines of the Christian denominations by terming them as “Churchianity” and not Christianity. By trying to incorporate and assimilate elements of other traditions in the Yogic world view, Yogananda was trying to adapt the Yogic tradition to the challenge of modernity and was also one of the pioneers of taking Yoga to the West which culminated in the creation of a global movement which today is serving as an instrument for the dissemination of Yogic ideas and meditative practices across the world.

The medium through which the cultural challenge Indian society and traditional ideas and intelligentsia were confronted within the nineteenth century, was sought to be negotiated and responded to by Yogananda, was through developing a kind of intertextuality and innovative cultural readings of the Western Christian tradition, a very specific kind of religious hybridity which, while incorporating the figure of Christ and some outward elements of terminology and organization, would doctrinally be true to the traditional Indic/Yogic worldview, which appears as an attempt to “digest” Christian or Western elements in a Hindu belief system. This can be seen as one of the responses of the Hindu Yogic tradition when it is forced (by the very nature and process of colonialism) to encounter the Western/Christian tradition in British India and also as a response to the greater awareness of the world in the nineteenth and early twentieth-century India. This shows a level of cultural intelligence implicit in the Indian spiritual tradition which enabled it to adapt itself to new conditions, new geography as well as a new ‘scientificity’.

(This paper was presented by Rabi Ranjan Sen at the International Conference on Philosophy and Praxis of Yoga conducted by Indic Academy and Indica Yoga on February 15th and 16th 2020)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.