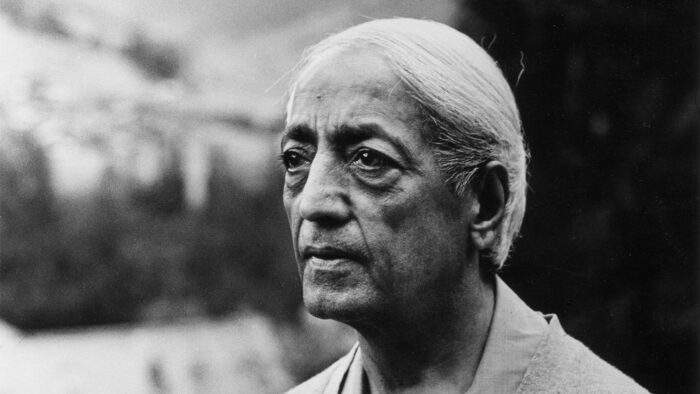

Repudiating connections with all organised religions and philosophies, one of the greatest Indian spiritual leaders, J Krishnamurti takes a different approach to living. Sans siding with the extremes like ancient or modern and theism and atheism, he talks about the ‘book of life.’ He doesn’t advocate tradition and questions the revolutions that have become tomorrow’s traditions. Krishnamurti has not written a commentary on the philosophy and metaphysics of organised religions but he comments on ‘living’. Krishnamurti’s oeuvre encompassing lecturing of over seven decades and over 2,50,000 pages has the sole aim, to bring about ‘transformation that doesn’t depend on knowledge and time’. On his 126th birth anniversary on May 11, let’s take an overview of what Krishnamurti had to say about human conditioning, limits of thought and knowledge, religious mind and much more.

The unconditioned man

First things first. Krishnamurti’s biography and his teachings must be studied parallelly, literally! As Krishnamurti spoke a great deal on unconditioning, understanding Krishnamurti’s biography will not help in understanding the teachings. However, Krishnamurti would refer to his childhood as a boy with a vacant mind. The biography tells us that Krishnamurti had his own conditioning but this quality of vacant mind didn’t let him condition himself.

Krishnamurti was born on May 11, 1895 in Madanapalle, the then Andhra Pradesh. He was a frail boy who survived many near-fatal Malaria attacks for a couple of years. He lost his mother during his early childhood, and he and his siblings were looked after by his father. Krishnamurti was also associated with the Theosophical Society during the early years of his life.

The Theosophical Society, founded by Russian mystic Helena Blavatsky, had predicted a coming of a ‘World Teacher.’ In early 1900, The Society, headquartered in Adyar, Tamil Nadu, was spreading its roots in India and the West. The boy Krishnamurti, who was playing with his brother Nitya at the Adyar beach, was ‘spotted’ by a leading Theosophist, Charles Leadbeater. Leadbeater claimed that the boy’s aura was indicating he was the ‘Upcoming World Teacher’. Thereafter Krishnamurti and his brother Nitya were adopted by a leading thinker and Theosophical Society President, Dr Annie Besant. He and his brother were taken to England and were groomed in Theosophical Doctrines. [i]

However, as Krishnamurti had always been, ‘a boy with a vacant mind’, started questioning the traditions, all the religious and theosophical doctrines and also the very coming of World Teacher. A worldwide organisation – Order of the Star in the East – was formed by the Theosophical Society to disseminate the message of the World Teacher. However, in August 1929, Krishnamurti disbanded the organisation and refuted the coming of the World Teacher. His dissolution speech, ‘Truth is a pathless land,’ contains the gist of his message where he stated that his aim was ‘to set the man absolutely, unconditionally free.’

Krishnamurti lectured for over 70 years ever since and he didn’t expound upon philosophy or religion, rather he spoke on day-to-day life, relationships, consciousness, fear, violence, conflict, sorrow, et al. He touched the subtleties of the human mind and prompted us towards a great spiritual inquiry. He extensively interacted with scientists, neurologists, religious scholars, writers, social figures and common men.

When Krishnamurti uses language

On the limitations of language, Tibetan Buddhist scholar Samdhong Rinpoche observes, ‘Buddha didn’t answer the questions which referred to the absolute… because language is limited. Language knows only alternatives. Beyond alternatives, language cannot comprehend.’[ii] He further adds that Krishnamurti is one of those masters who had understood the deceptivity of I, me and that image. ‘Krishnamurti described it in modern language. He didn’t use technical or philosophical terms.’ [iii]

David Skitt, who has edited many of Krishnamurti’s books, underlines the need for readers to get accustomed to Krishnamurti’s language. ‘Though Krishnamurti’s vocabulary is simple, it is by no means easy to understand either on a first or later reading. As he said, “You have to learn my vocabulary, meaning behind words.”‘[iv] Krishnamurti was rather aware of the conditioning associated with language. Each word brings certain associations in its trail. That is what Krishnamurti meant by conditioning. The brain associates word as per its conditioning, earlier experiences and preconceived notions. The word flower may remind us of trees, gardens and colours and may prevent us from ‘seeing’ the actual flower. Krishnamurti was trying to take us to the arena where the import of the word lied beyond subjective linguistic associations. Therefore, at the very outset, it is pertinent to know the peculiarity of Krishnamurti’s words and language.

Using words just as markers, symbols and buoys, he was rather conveying what lied beneath the word. He simply pointed out what is and insisted that we understand what is and not what we perceive something to be. Krishnamurti’s discourses are never intended to bestow any new understanding of words or language, nor is he here to build a new rhetoric. He is not building a new dogma or a system or a method with words. Instead, he is insisting us to raze all tall structures of conditioning that our brain has raised through centuries.

He didn’t use words and language to philosophise, intellectualise or verbalise. He simply used them as a vehicle to convey ‘what is’. Thus, understanding ‘what is’ may probably happen when we simply stay with what he is pointing out without translating it into our own language. Before delving deeper into the etymological art of Krishnamurti, let’s first see what he meant by art. The word art may remind us of creativity and aesthetics, but what Krishnamurti implied was something radically different.

The word art means putting everything into its right place.[v]

Conflict, fear, thought, memory, knowledge: Contents of consciousness

Krishnamurti examines how conflict is the root of psychological problems. While explaining conflict, fear, thought and knowledge, he shows how they are interrelated and how one arises from the other. Psychological becoming leads to conflict. His fundamental concern is why have we accepted conflict as something inevitable and unavoidable? Can there be life without conflict?

Conflict is a very destructive thing, inwardly as well as outwardly; and I want to find out if there is a way of living without being in conflict.

The ending of conflict is essential because conflict kills sensitivity, intensity and passion. The mind in conflict is incapable of finding out the unknown. When Krishnamurti was invited to The United Nations, he pointed out our attention to the very fact that conflict begins with individuals and families and finally reaches the global level. When individuals are in conflict with themselves, how could we talk of peace? Therefore, conflict is the beginning point to identify the problems. He doesn’t define conflict, simply points out the fact that it exists wherever there is division. And how thought is responsible for conflict?

Thought is the response of memory, the past. When thought acts it is this past that is acting as memory, as experience, as knowledge, as opportunity[vi]

Stephan Smith, a long-time associate of Krishnamurti schools, observes that Krishnamurti offered a new meaning to meditation. ‘It is not “new” as opposed to the “old”: It is new in the sense of never having been old; it is to this that it owes its freshness and immediacy. It is at the beginning because it is always beginning, that is, it is free of history. History not in the sense of the record of time past, but history as psychological accretion, everything thought has accumulated as knowledge and which it presents to itself and to the world as “me”. “The breaking down of the meditator is also meditation,” for “this total process of learning is explosion in meditation.” Obviously not for the faint-hearted! One of the features of Krishnamurti’s meditation is the stress he lays on emptying the mind. “True meditation is this,” he says, “the emptying of consciousness.” And, perhaps at this point we should remind ourselves of what he means by consciousness.”[vii]

Choiceless Awareness: Core of Krishnamurti’s teachings

All of Krishnamurti’s teachings can be summed up in ‘awareness’. He spoke about passive and Choiceless awareness which is ‘observing’ ‘what is’.

Awareness is the silent and Choiceless observation of what is; in this awareness the problem unrolls itself, and thus it is fully and completely understood. [viii]

By awareness, Krishnamurti meant purely being in a moment or observing without evaluating. According to him, our fears, anxieties, thoughts, pleasures and constant efforts of bettering comprise the content of human consciousness. Thus, our seeing or listening, or any action primarily comes from the content of consciousness and awareness can come only when we vacate the consciousness with its content.

To be factually and choicelessly aware of all that is in yourself, to observe it without effort – it is in the state of effortless awareness that there is a total revolution. [ix]

Or,

You have to see yourself as you are from moment to moment without interpreting what you see and without accumulating knowledge about yourself; you have to observe with Choiceless awareness.[x]

This Choiceless Awareness is something Krishnamurti said can ‘end the sorrow’ or determine our ‘approach to the problem.’

The approach to the problem is more important than the problem itself; the approach shapes the problem, the end. Choiceless awareness of the manner of your approach will bring the right relationship with the problem.[xi]

When Krishnamurti’s official biographer Mary Lutyens approached him for the gist of his writing, he wrote ‘Core of the Teachings’ where he said,

Freedom is not a reaction; freedom is not a choice. It is man’s pretense that because he has choice he is free. Freedom is pure observation without direction, without fear of punishment and reward…Freedom is found in the Choiceless Awareness of our daily existence.

Krishnamurti and real challenge:

Krishnamurti has imparted different insights on war, artificial intelligence and peace. He doesn’t take a socialist approach that changing the social order will help change man. He asks each of us to turn inward and understand ourselves. Michael Mendizza, documentary filmmaker on Krishnamurti, has recently released a coffee-table book on Krishnamurti’s teachings, reviewing them decade by decade. It’s a kind of a study book giving a bird’s eye view of Krishnamurti collections. According to him, the constant challenge is Krishnamurti’s true legacy. He says we are operating even Krishnamurti through content of consciousness. Mendizza makes us aware of the paradox to use concepts to go beyond concepts. There are two states of consciousness –thought, which makes the mind mechanical and silence, emptiness – the absolute. Krishnamurti insists there is no intelligence at the level of thought, the mechanical process.[xii]

Prof P Krishna, an exponent of Krishnamurti teachings, in his book, ‘A Jewel on the Silver Platter,’ says, ‘Krishnamurti was one of the most original thinkers of our time who investigated fundamental questions about the purpose of life, the true meaning of love, religion, time, death without seeking answers in any books or scriptures ….Like Buddha, he sought answers to these questions through observation, inquiry and self-knowledge and arrived at a direct perception of truth which lies beyond intellectual concepts and theories…. What he says may have been said earlier by others but he came upon the truth of it by himself’[xiii].

Krishnamurti’s philosophy may have parallels with metaphysics of Upanishads, Zen or Shunyavada of Nagarjuna but what makes him original is the resonance with Buddhist saying, ‘If you meet Buddha on the road, kill him.’

Footnotes:

[i]For biographical details please refer to biographies, please refer to official biographies by Mary Leyutens and Pupul Jayakar

[ii]Rinpoche Samdhong and Mendizza Michael, Always Awakening, Krishnamurti’s Insight, Buddha’s Realization, Hay House, 2016, p.46

[iii]ibid 65

[iv]Skitt David(ed) in the Introduction to To Be Human, J Krishnamurti, Shambhala, 2011, Kindle edition, location 210)

[v] The art of listening, seeing, learning and living, Public Talk 4 Ojai, California, USA – 10 April 1977 (Source for all Krishnamurti talks henceforth is https://jkrishnamurti.org/ accessed on January 28, 2020)

[vi]Krishnamurti J,Urgency of Change, Ending Thought, Littlehampton Book Services Ltd, 1979

[vii]Smith Stephan, A Meaning of Meditation, a Revolutionary New Approach, https://www.krishnamurti.nl/publicaties/lezingen/104-meaning-of-meditation visited on May 5,2021

[viii]Krishnamurti J Commentaries on Living I, Krishnamurti Foundation of America, Ojai, 1956,page 140 (commentaries hereafter)

[ix] Krishnamurti J, Saanen, 1st Talk, 1962 jkrishnamurti.org

[x]Ibid

[xi]Commentaries page 138

[xii]Mendizza Michael, Unconditionally Free, Krishnamurti Foundation of America, 2021

[xiii]Prof Krishna P, A Jewel on the Silver Platter, Pilgrims Publishers Varanasi, 2015, p. 273

Image credit: Krishnamurti Foundation Trust

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.