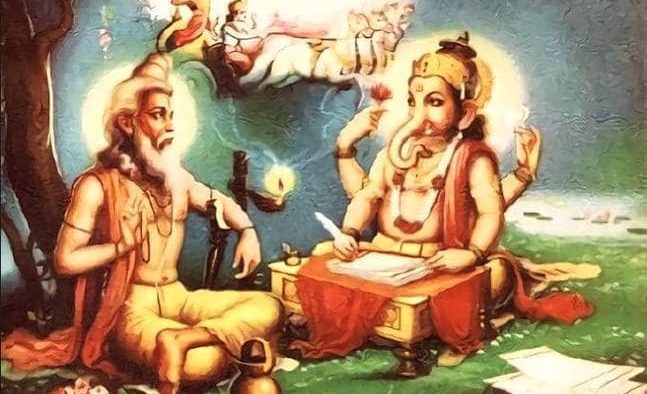

The role of Ganesha in Mahabharata is quite well known, the great conversation between the composer Vyasa and the scribe Ganesha is one of the most famous episodes of Mahabharata. Yet, this is one of the least reflected upon episodes- in terms of its perspective and metaphoric relevance. The beauty of the play between the two obfuscates the sheer immensity of the perspective beholden beneath.

Vyasa was not only a sage of the highest order but also an eloquent poet. He was unfortunate enough to witness immense destruction and complete annihilation of his entire clan in his own lifetime– i. e., the great war of Kurukshetra between his grandsons Kauravas and Pandavas. The sage was greatly moved by this tragedy.

Only he could comprehend such an enormous experience, recognize universal elements in it, and express them in a manner that touched human hearts of all times. It was natural that he thought of composing a mahakavya on this great tragedy, for the benefit of mankind, that could stand the test of time, which came to be known as Jaya or eventually, Mahabharata.

He was greatly compassionate and looked at both sides of the warring Kshatriyas with equal concern, love, and affection. Yet he could see their rights, wrongs, and follies, which collectively resulted in this war and complete annihilation.

His reflections on the tragedy gave him an immense understanding of the humanity, and insight into human behaviour. He sympathized with humanity in its difficulty to appreciate what is dharma or adharma, and act accordingly. Yet he was clear that it was dharma alone that could uplift humanity. With both his hands joined, he implored upon the humanity to uphold dharma – the Mahabharata says. He often felt sad as the society was losing the ability of dharmic discretion.

He transferred his insights into a mahakavya. In his own mind, he had already conceived, formed, and constructed it. But yet, it had to be brought into this world in the form of a written mahakavya and he was wondering who would scribe for him, and how long would it take.

Knowing his mind, Lord Brahma at once came down to Vyasa’s ashrama to bless the great sage. Vyasa put forth his quest for a scribe, and Lord Brahma suggested none other than Lord Ganesha. But Sage Vyasa must perform a penance, and prevail upon him.

This is a running pattern in many of the ancient epics. Bhagiratha had to perform an exclusive penance to Lord Shiva to ensure that Ganga would not overrun the earth with her mighty fall, even after he obtained a boon from Lord Brahma to make her come down to earth from devaloka. There is an exclusive penance and performance for every achievement.

Sage Vyasa sat on a platform under his favourite tree in his ashrama and meditated upon Ganapati. Could anybody not respond to the earnest call of Sage Vyasa? In a few moments there was the great Lord Ganapati – the vighnakarta and vighnaharta – the cause and the resolution of all obstacles in life.

With great devotion Vyasa welcomed him, and offered him a seat on that very platform under the tree- where Vyasa had performed his penance of meditation and writing all his life. Vyasa then submitted his great desire to Ganapati. The challenge posed by Ganesha is quite well known. He was quite happy to be a scribe for his mahakavya. But he needed Vyasa to be at his best, and never give Ganesha a moment to pause. If there was ever one, Ganesha would have no other option but to quit, and the mahakavya would be incomplete.

At the outset, it looks like Ganesha was short on patience; although he was not averse to be the scribe, he wanted to enjoy it as well. However, it could as well be said that Ganesha brought out the best of Sage Vyasa. This challenge uniquely shaped the Mahabharata which otherwise would be different. He seemed to be creating a hurdle, but in reality he was eliminating one.

Sage Vyasa knew Ganapati would not be easy. It was now his turn to go deep into his self, and find a solution. At last, Vyasa agreed, but in return he sought that Ganapati would not write a word without reflecting adequately and internalizing it, understanding the meaning, context, and importance of it in the backdrop of the larger story.

This, of course, gave him enough time to think and compose complex, meaningful, insightful, and timeless stanzas that took much more time for Ganapati to understand, than for Vyasa to compose. Vyasa packed as much beauty, emotion, and complexity in every shloka.

It was the turn of Ganapati to smile. He knew that the Sage would now be always ahead of Ganapati, and they would both be engaged in composing and writing a Great Poem together. The great duel of thoughtful composition and reflective writing continued between them unhindered, like the flow of a great river.

Ganapati had no option but to pause, reflect deep, and sometimes lose himself in appreciation, giving Vyasa enough time, leisure, and space. As a result, even to this day Mahabharata stands relevant, throws more meaning with each recital, and invokes dharma in the minds of both the reciters and listeners.

Ganapati asking Vyasa never to give him a pause, and Vyasa in turn seeking an intense understanding of the verses has much more than a mere play between the two. This simple story is a metaphor of how Great Epics of insightful writing are realized in a culture.

Ganapati represents the recipient of this work. He requires a highly engaging work, which captures his attention throughout, and is in the right rhythm. If you look at all works of the past in India, this is true. They connect with the society and present the entire narrative in a rhythm that appeals to the audience, and are prolific throughout. They make a difference to the daily life of the society and at the same time elevating them to see something beyond.

On the other hand, there is an expectation even from a simple scribe in Indian tradition. A scribe represents the reader/ listener audience of the society, often called as rasika in the Indian tradition. A scribe has to internalize the work, before putting anything in hard writing. A society that nurtures such scribes, readers, rasikas who have the respect, appreciation, and patience to internalize can grow poets of Vyasa’s caliber.

Only such a culture can give the Vyasas the space to give the right shape to that deep poem residing in the depths of their mind. They alone can help a Vyasa convert their insights into great pieces of work that stand the test of time.

Every Vyasa needs a Ganapati to conceive his/her Mahabharata – one who loads a great poetic responsibility on the poet, but at the same time is willing to take the burden of internalizing, thereby giving space to Vyasa to be true to his vision. Any culture or civilization expecting great works should be ready for such burden too, and should rather enjoy it.

The choice of Ganesha as a scribe is equally interesting– he is both the vighnakarta and vighnaharta, one who creates and eliminates hurdles. It is in that friction that greatness emerges. Vyasa has to go through that process. In general, the process of creation has its own rhythm and dynamics. One has to go through that fire for beauty, greatness, and timelessness. At the highest level, it is a creation, and in epics and puranas, we see even gods performing tapas to shape a reality or realize a creation.

It is also interesting to note that Sage Vyasa forbade the public recital of Jaya, until the right time came. While the work was in composition many personalities who were important characters in the Great Poem were alive. The present was not to be affected by the Poem. Thus, the recital of the poem, and the guidance to the larger society had to wait until the right time.

This signifies the importance accorded to the end result. However beautiful the creation is, its time has to come, and one has to wait for it, which is also a part of the tapas. One is to never be lost in the beauty or charm of one’s creation, it is rather the eventual impact that is more significant.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.