Last week there was excitement for the Indics of Bengaluru. ‘Parva’ – Dr. SL Bhyarappa’s legendary Kannada novel – was on stage in English. Produced and managed by Eneno Ase Media and Entertainment it was directed by the multifaceted Shri. Prakash Belawadi – Theatre person, Thinker, Actor and Culture Critique. Published in 1979, the novel was written over 3 years of elapsed time with many years of preparation before. It has a cult following across generations and virtually has the status of an epic in our times. Nearing 50 years but the fascination and conversation around Parva has not ceased.

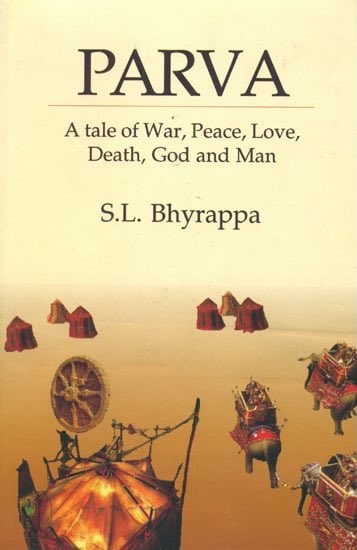

Parva has drawn both fans and critics in equal measure. It is translated into most Bharateeya-Bhashas and is possibly the most sold English translation from Sahitya Academy. Left Liberals and Seculars grudgingly appreciate the novel. In form and substance it offers them material to problematize the culture. Indic Modernists have an unabashed appreciation of the novel for the composition it offers to see modern ideas in an ancient setup. Traditionalists have maintained a cautious distance appreciating literary genius but highlighting substantive problems in it. Thus, ‘Parva – the Novel’ is a legend of our times in its own right.

Parva – The Play

A play of 8 hours with 5 Acts and 4 Intervals is a marathon in itself. An open-air theatre suits such a longish extravaganza, much like Yakshagana of previous decades. To pack it into the confined stage of a proscenium like theatre is a daring act. Shri. Belawadi has not only dared but succeeded in this phenomenal adaptation. The play had already seen successful runs in Kannada with appreciation. Now the English audiences got to experience this grand retelling and reimagination. Actors were largely above board with some exceptional performances. Even a simple 2 hour play is never without a performance flaw. Here was an 8 hour play with negligible omissions. The stage was simple and static. Yet it was potent for creative lighting to bring it alive and made fresh for each scene, well supported by a costume-design which reflected personas and situations. A remarkable use of the stage space and position for each character to reflect situations, mood and importance. Haunting music became a role in itself while being invisible. All this technical genius transformed itself into an accessible theatrical experience for all audiences.

(Figure 1: A still from the play – An older Kunti reflecting on her dilemma’s as a young woman, reminiscing her conversation with husband Pandu and Madri)

‘Parva – The Play’ is largely faithful to the ‘Parva – The Novel’ in terms of its substance. But the theatrical experience is Shri. Prakash Belawadi’s creative imagination. Holding a learned audience to an 8 hour indulgence is a phenomenal achievement. Mahabharata will always remain a fascination for the ‘Bharateeya Manas’. Yet the larger credit goes to the staged version, Shri. Belawadi’s stage vision and the performers. The hall was full and a significant section of the audience stayed through. While it says a lot about – Mahabharata, SL Bhyrappa and the novel itself, it says as much about an audience willing to sit through a marathon patiently. The audience, truly from a wide spectrum, applauded this scintillating performance. That it ran like a sprint made things easy and a joyful experience. It was an entertaining, engaging performance provoking the audiences to reflect and respond.

Everything else could be perfect but nothing can compensate for actors with a good hold on their craft. It’s challenging when you are staging something based on Mahabharata. Three actors truly carried the ensemble throughout – Kunti, Draupadi and Srikrishna. Divya Raghuram, who played the role of Kunti, is an outstanding actor with years of experience. Her mastery over the craft was in full display in every gesture and word. Kunti is the most intense character in Dr. SL Bhyarappa’s Parva. Divya carried that weight on her shoulders with poise, grace and understanding. Draupadi is an equally complex character in the novel. Siri Ravikumar – a relatively less experienced actress – played the role impactfully. All characters in Parva go through enormous inner struggle. Each finds their individual excess punctured by the other at some stage. Srikrishna alone is the exception. It is the only role in Parva mostly etched in the mould of the original Mahabharata. He stays above the ‘Samsara Sagara’ and cruises through the ocean of sorrow. It was delightfully played by a very young actress – Shibani Rao – who grasped the enormity of the role. Of the men – Duryodhana played by Abhijeet Shetty was exceptional. Krishna Hebbale as Karna was remarkable, portraying both the dilemma and tragedy very well. Harish Sheshadri as Dhritarashtra stood out. Nameless supporting characters were placed well to emphasise specific moments and aspects in each scene. Some present in the novel and others a thoughtful imagination of the play itself. They did their job neatly.

A critical review of a play like Parva cannot escape two other dimensions. A comparison with ‘Parva – the Novel’ is in order for obvious reasons. One must explore the similarities and differences between two. At the same time viewing both the play and the novel from the lens of Vyasa Mahabharata cannot be avoided. Mahabharata as an epic carries a cultural and civilizational importance and hence any derivation, adaptation, retelling cannot escape a conversation with the original. The critical question is what value does an adaptation bring to the existing universe where the original is at the centre or to the current times? Hence, the Play and the Novel are to be situated in its universe.

Parva – The Novel and Vyasa Bharata

Vyasa’s Mahabharata is complete. It portrays clear conflict between Artha-Kama pursuers and the seekers of Purushartha. It presents their turmoil, striving for clarity & and achieving clarity in the right measure. It is a complete treatise of the Purushartha portraying the complex interplay between Dharma, Artha, Kama, Moksha through the large universe of 1 lakh Shlokas. Vyasa Bharata is a peak Vedic Society with clarity & confidence in Moksha and dharma.

(Figure 2: Parva – The Novel by S.L. Bhyrappa)

‘Parva – The Novel’ is like a proto-Vedic society yet to attain Dharmic clarity or a post-Vedic society that has lost Dharma clarity. This reduction helps the novel underscore the difficulty of realising Dharma-clarity in the real world. Artistically, it is a triumph of structure, plotting and characterization presenting characters of Mahabharata in the flesh and blood. It makes a compelling reading and leaves you wonderstruck. Yet, the novel is a slice of the Vyasa Bharata in terms of substance cut through the sensitivities and sensibilities of a particular time period – the 70s. The novel is a partial reduction of the holistic Purushartha universe into a lesser Artha-Kama plane. Moksha is a suspicious idea and Dharma without clarity in the novel (The Shuka episode for instance). Thus, the light of Veda Vyasa dims into a darker universe of the night.

‘Parva – The Novel’ presents a stark Artha-Kama clash between characters each searching blindly and in vain for the balance of Dharma. Every character strives for that elusive Dharma in its sookshma. This is achieved through the portrayal of the internal turmoil of characters while still struggling to realize ‘clarity of Dharma’. Consequently, the whole novel is on the Artha-Kama plane although Dharma and Moksha make a cultural difference on that plane. In this penchant to characterize the sookshma – the subtle – the novel ends up giving an impression that on certain matters there is no clarity. But Vyasa Bharata is an epitome of clarity even while portraying the elusive nature of subtle Dharma. The novel still is a multidimensional exploration of what Dharma is. Yet this choice of internal turmoil as the central feature, presented through monologues and deep moments of confusion, has its implications.

Parva – The Play

A Play, however long it is, cannot bring all dimensions in equal measure from a novel. Parva – the play’ retains internal turmoil as the chief instrument on the stage. Substantively it picks two aspects from the novel as its anchor – the righteousness of Niyoga through which the Pandavas were born and staking of Draupadi in the Dyuta Sabha. Other explorations of the novel are not totally eliminated in the play. But they become satellites to these major planets of the Parva Solar System.

This anchoring results in a strong presentation of its women characters – much in line with ‘Parva – the Novel’. However, it renders men without agency for they become answerable to questions raised by Kunti and Draupadi. This reflects in the portrayal of Pandu and Dharmaraja respectively. The psychological space occupied by Draupadi and Kunti, when present and otherwise, makes other characters less emphasised. While Draupadi’s anguish has roots in Vyasa Bharata, Kunti’s sense of being wronged is a creative liberty assumed by Dr. SL Bhyrappa in the novel. The novel balances this aspect through a variety of other situations. This assumes a larger proportion in the play as it anchors on the two women. It also ends up creating space for modern preoccupations to be read into the Mahabharata universe. This further narrows down Dharma exploration. While this is a creative liberty assumed in the novel itself, there is scope to balance this out in the play given its constrained time and space.

Given the limits of time, ‘Parva – the Play’ could not have done justice to all characters as portrayed in the novel. But there is scope to retain the focus on the ‘complexity of decision making’. Suppression and oppression of men and women ought to be a sub-element of this larger exploration. The novel itself explores the psychology of women a lot more than men. But the technique used by the novel is that of subtle journeys in the mind. In their actions, the novel strives for a greater justice to both men and women. In the play, this psychological journey is transformed onto the ‘material’ plane completely as it is the ‘visual’ medium. A thought process in the mind is transformed into an absolute flesh and blood reality – assuming a level of emphasis not found in the novel. This results in the turmoil of women looming large over the entire play. Men do not get enough opportunity to present their Dharma exploration. They appear self-indulgent and confused.

(Figure 3: A still from the play – Dhritarashtra and Gandhari)

This exploration on a purely psychological plane is relatively easier in literature than in theatre. The theatre presentation of the novel requires the exploration of a ‘non-real psychological’ plane on the stage. What appears in the novel as the intensity of the moment must not appear as a larger reality across time. Just as Dr. SLB has assumed creative liberty to portray a certain dimension of Vyasa Bharata, the staged version itself may need a creative distance from the novel to suit the medium of the stage. Language also plays a role. What may have been a weighty exploration in Kannada (with Sanskrit words) may appear a bit too material and mundane in English. The sense of ‘Bhadra/Mangala/Auspicious’ is harder to achieve in English while in Kannada/Sanskrit the word can compensate for the tenor and situation. These are critical challenges for the play as well as the upcoming movie.

Characterization in the Novel and the Play

A few other characters have assumed comical dimensions. Theatrically it makes sense as it brings relief to an otherwise very serious play. When nameless supporting roles acquire this dimension it complements the larger play very well as well. However, a principal character like Sanjaya presented in this tenor takes away a very critical dimension from Mahabharata. A Suta like Sanjaya constantly chiding Dhritarashtra for his omissions is the hallmark of Vyasa Bharata. It underscores the agency non-Kshatriyas enjoyed in the cultural space occupied by the Kshatriyas. It is the strength of the erstwhile Varna-Jata-Kula order. The novel partially and the play completely takes away this dimension. A self-indulgent, selfish, compromised, comical Sanjaya brings only entertainment on the stage. Sanjaya was Vyasa’s favourite Shishya and there are references where he is quoted alongside Shuka ahead of other disciples. Nevertheless, it must be said that the actor Apurva Aniruddha plays the role presented to create a memorable experience.

Several other characters go through this journey of creative liberty becoming weak in the novel, and hence, in the play. Vidura becomes a confused man with some moral ambition but without clarity. Pandavas in general are without agency. Bheema alone has a greater presence in the novel. In the play, this exploration is severely curtailed as the women characters assume larger space. Arjuna with a lesser presence in the novel finds himself merely responding to situations in the play. The contempt that the novel has for Nakula-Sahadeva is carried over to the play while Vyasa Bharata is quite glorious about both. Sahadeva in particular is a guptagaminee in Mahabharata but plays a crucial role intermittently. Parva – the Novel itself makes Pandu very weak in order to create a stronger Kunti. However, Vyasa Bharata retains equal strength in both and yet explores the very same questions. The assumed creative liberty of the novel does not seem to result in substantial aesthetic and cultural fruits. The play could assume some distance from the novel in future to restore balance.

The biggest victim of all is Dharmaraja Yudhisthira himself. The novel itself paints him as a good man without wisdom and backbone while the play unwittingly amplifies it. Maharshi Vyasa portrayed Dharmaraja as the only man ascending to the heavens with his mortal body. Any retelling, reimagination, exploration of Mahabharata must deal with this dimension. The caste superiority-inferiority is also overplayed in the novel spilling over to the play. Suta-s are very much royal in Vyasa Bharata. Karna only suffered the wrong of being abandoned at birth and no more discrimination. Exalted sages Lomaharshana and Ugrashrava Souti are Suta-s themselves. Ekalavya is killed by Srikrishna much before the Kurukshetra war. He belonged to the privileged royalty of Nishadas with allegiance to Jarasandha – as Harivamsha Purana elaborates. Another interesting moment in Parva the novel is Vyasa and Bheeshma coming face to face. They return weak and without answers to their questions in both the novel and the play. But on those very matters, Vyasa Bharata assumes enormous clarity and answers all questions the novel and the play raise. These are matters that future adaptations and productions could consider and resolve.

Creative Liberty

All this leaves us with a larger question. What does creative liberty mean in the context of civilizational epics like Mahabharata? The moment we pick a few elements from the larger universe for emphasis it leads to a kind of altered universe. Suffice to say that creative liberties ought to operate within the universe of the original and not completely create a new universe. They must highlight a dimension of the original without affecting any other existing dimension. Any interpretation ought not present the original in a light contradictory to its original vision. At the least, assumed creative liberty ought not to make space for problematic modern readings/theories not consistent with the original Mahabharata. Unfortunately, ‘Parva the novel’ makes way for it. It was written in 1979 and reflected artistic/literary sensitivities and socio-political realities of the 1970s. It drifted to being a view of contemporary life but using the structure, lens and instrument of Mahabharata. In 2023, new adaptations will need to assume different forms and occupy different positions in the Mahabharata universe while holding a mirror to a side of the original.

(Figure 4: Post-play ensemble of actors on stage)

Dr. SL Bhyrappa opened the body of Vyasa Bharata to observe its critical elements. In his new synthesis he picked only a few elements through which he sought to raise questions that Dharma is concerned about. However, the synthesis remained only at the questioning level without exploring answers which too were part of Vyasa Bharata. Further, the moment he brought them from the Puranic universe to the real world it assumed a greater Artha-Kama dimension. Questions raised were sporadic without offering a consistent worldview. Such an exposition only amplifies being wrong and being wronged reflecting only contemporary concerns. That may not be fair to either Vyasa Bharata or to our civilization.

As mentioned earlier, the Novel was a journey into the psychology of select characters. It’s a psychological journey through the pages. This creative liberty worked well in the form of a novel as it is literature. A staged version (a movie much more) by default creates a material universe through the visual medium. The stage is very much a 3 dimensional physical space. The psychological journey becomes a material one. Hence, the characterization and their emphasis require a distance from the novel. These are questions about how a substance must be carried from one medium to the other. By default, the form of a novel cannot carry the complexity of an epic in verses. But the perils of the plane of realism can be somewhat avoided in a novel. In a play or a movie it is more difficult. As Parva triumphantly enters into the movie-medium, these are important questions to ask and find answers.

Nevertheless, Parva – A Play in English is a triumph of the theatrical genius of Sri. Prakash Belawadi. An impactful production that will continue to make waves. We will talk about it for a long time to come. It offers a template for how classic works should be adopted and presented in an engaging and thoughtful manner. It will further evolve in a continued engagement with the audiences. Time will tell what space it occupies in the Mahabharata universe and where it will beam its light on. Hopefully it will reignite an interest in the original Vyasa Bharata as well.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.