Would you consider someone who lived thousands of years ago and wrote in Sanskrit to be a…hopeless romantic and on occasion, quite a flirt?

If your answer is not a resounding yes, then consider this. What do you find more sensuous and evocative— an Instagram post about missing a loved one or the poetry of a lovelorn man talking to a cloud about the beauty of his wife, the devastating love they share, and the details of the most intimate moments between them, because he cannot bear the pangs of separation between them?

Except, when this man talks, he is not merely communicating. He is, instead, drowning himself deep into the sea of emotions and for his words, he chooses the best of pearls to string together a beautiful necklace of a poem. Of course, it’s the genius of the poet behind the man that really holds the reader hostage, not the man himself. The poet is none other than Kalidasa and the poem in question here is Meghaduta.

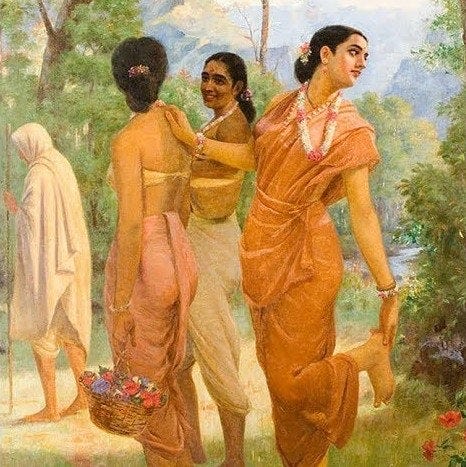

Raja Ravi Verma’s Shakuntala, based on Kalidasa’s play of the same name.

Raja Ravi Verma’s Shakuntala, based on Kalidasa’s play of the same name.The legend, however, has it that he was not born a genius. He was a fool who was passed off as an erudite prince to a princess by someone with a grudge. When she found out, she was enraged and is believed to have berated him. She then abandoned him at a local Kali temple, where he took up the worship of the fierce goddess. Foolish as he was, his simplicity and devotion still won her over and she granted him a boon like no other. In another version of this, fictionalised in a Hindi play titled, Ashadh Ka Ek Din, by Rakesh Mohan, Kalidasa was a young poet in love with a woman from his village. His poem Ritusamhara makes him famous after which he is invited to become a court poet and later ends up marrying a princess. It is likely that the love he left behind in the village is the inspiration for Meghaduta.

Either way, his genius earned him much fame in his lifetime and beyond. To date, he is known across the world for his unparalleled way with words, both as a poet and a playwright. While not much is known about him with certainty, it is widely believed that he lived around fifth century in either the modern day Orissa or Kashmir.

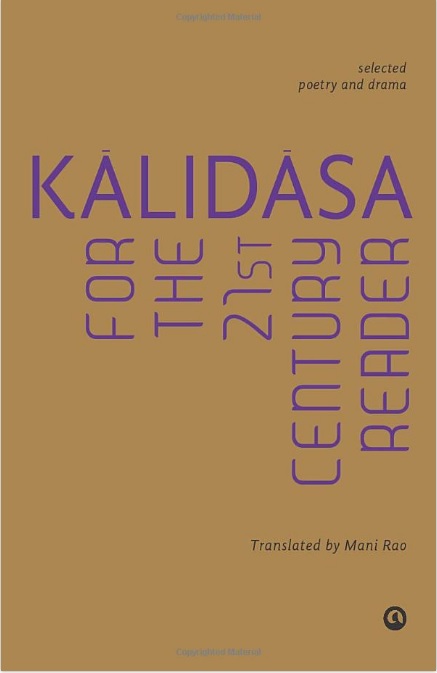

But what exactly makes him the legend that he is supposed to be? “He is sensitive to beauty in nature, and holds nature as more perfect,” says Mani Rao, 56, who is a writer and a poet. Based in Andhra Pradesh, she has translated seven of Kalidasa’s most popular works in her book, Kalidasa For The 21st Century Reader, namely Meghadutam, Abhijnana Sakuntalam, Rtusamharam, Raghuvamsam, Kumarsambhavam, Malavikagnimitram, Vikramorvasiyam (the names here are in Sanskrit because that is how Rao addresses them but elsewhere in the article they are referred in Hindi). Considering his brilliance to be his understanding of human nature, she explains, “he has insight into human nature— is sympathetic to obsessive love, passion and longing, laughs at infidelities and abuse of power, and at love-politics, and admires truth and courage.”

“In Meghadutam, we see a lover’s longing and fantasies and in Shakuntalam the ways of attraction, attachment, trust and betrayal, and how circumstances create misunderstandings,” she explains. Where he has the knack for capturing moods of passion, Rao points out that his work also shows instances where duty clashes with desire. In that, what he wrote was akin to how we all too often too struggle to balance our personal and professional lives, which cause dramatic episodes every now and then.

Rao found Kalidasa in her undergrad when she studied English and Sanskrit. She believes that it’s important to read him for two reasons— to understand how the Sanskrit literature and dramatics have been shaped by his figures of speech and meter as well as to grasp deeply what India was like at his time. “Reading [him], you will identify, and find yourself thinking about, intrinsic Indian values,” she says, “you will relate to landscape vignettes that are still very much Indian topography.”

Abhay K. would agree to this. The 41-year-old poet-diplomat found Kalidasa as a matter of chance while he was posted in Nepal until 2016. People there would often talk about Kathmandu as being Alkapuri, the mythical city referred to in Meghaduta. But it wasn’t until 2020 that he read the poem, after coming across another reference to it. And once he read it, he read it over and over again. He read translations by H. H. Wilson, Col. H.A. Ouvry, Mallinatha, and Chandra Rajan, before working on his version of it. A prolific poet, editor, and translator, he has since translated two of Kalidasa’s works— Meghaduta and Ritusamhara.

Abhay K. who is from Bihar and currently India’s Ambassador to Madagascar finds the poet’s knowledge and descriptions of flora and fauna to be amongst the most notable features of his work. “It [Meghaduta] highlights the importance of flowers, plants, animals, seasons, rains, rainbows, winds, sun, moon, stars, stones, rivers, mountains among others things—animate and inanimate, in our love-life, without which we would gradually become biorobots obsessed with numbers and statistics, dealing with various kinds of growth rates, and living a dismal life on a planet marred by loss of biodiversity and extreme climatic events,” he says.

It is also this intermingling of love for a person and for the Nature that he considers to be eternally relevant. Who but Kalidasa would imagine, Abhay K. asks, rivers as sensuous women in whom his cloud-friend may very well take an interest as it journeys from the central Indian plains to the Himalayas? In Ritusamhara, Kalidasa goes even further. “[It] doesn’t merely acknowledge the interrelationship between humans and nonhuman realms, but goes beyond it in underlining the vital role the flora and fauna play in shaping human culture and civilization and how in their absence we humans would be reduced to nothing but machines,” he explains.

Sharing a few verses from the poem, he believes it to be an example of ecopoetry which exhibits the poet’s capacity for deep empathy—

Like jade fragments, the green grass rises

spreading its blades to catch raindrops,

red Indragopaka insects perch on fresh

leaf-buds bursting forth from the Kandali plants

the earth smiles like an elegant lady

draped in nature’s colourful jewels. 2-5

Aroused by the sun rays at sunrise,

Pankaja opens up like glowing face

of a young woman, while the moon

turns pale, smile vanishes from Kumuda

like that of the young women,

after their lovers are gone far away. 3-23

The fields covered with ripened paddy

as far as eyes can see, their boundaries

full of herd of does, midlands filled with

sweet cries of graceful demoiselle cranes.

Ah! What passion they arouse in the heart!

Speaking about Kalidasa’s genius further, Rao adds, “[He] does not draw attention to his craft, we never feel that he has made a word choice for the sake of meter,” explaining, “it always feels like the accurate word has been used.”

Taking an example from Meghadutam, she says that the poet has used a particular meter, i.e., the mandākrānta meter of seventeen syllabic lines to create a slow, meandering rhythm, which feels right for a cloud’s voyage. “The way Kalidasa works with the meter is so deft, the reader never feels that a word is contrived, or chosen for its syllable length or phonetic features rather than for aptness of meaning and suggestion,” she says.

But if he has his delights, he may also be seen to have his faults, especially if his works are read from a modern and progressive lens. The women in his works, most notably Shakuntala, are mellower and almost devoid of their personal agency. Their lives and emotions are often shaped by men around them. Even when they do have a pull over the male characters, they are either elevated to the level of royalty or celestial maidens. Rao points out that it was probably a result of being a court poet as well as the society he lived in.

However, if he is truly so amazing a wordsmith, why isn’t he more widely read? While most Indians may have heard his name, very few seem to have actually read him even in translation. Rao shares an incident from when she was supposed to participate in a panel discussion about Kalidasa at a literary festival in Mumbai. Her contact, also a poet in her 30s, asked if they should get an ‘orange person’, likely a euphemistic way of referring to a Hindu nationalist, for the discussion, insinuating that reading Sanskrit must be akin to reading religiously fundamentalist work. While Kalidasa’s works have plenty of references to Hindu lore, one wonders if we should allow ourselves to refrain from reading him out of fear of a politically and religiously charged climate in present day India? At the same time, would this nationalistic segment be receptive to some of the bolder themes in Kalidasa’s works, such as erotica?

In any case, Rao feels that English translations of Sanskrit texts too could be done better. “By translating Kalidasa into say Victorian style poetry with expressions such as “Lo and behold”, you are neither locating him in his time and place, nor in the reader’s time and place,” she says. For instance, when Dushyant calls out to his love-interest Shakuntala, it might be more appropriate to translate it as a flirtatious “hey sundari (hey beautiful)” rather than the English royal-speak “hail, lovely lady.”

But this may have a lot to do with the fact that earliest translations of Sanskrit texts, including Kalidasa’s Shakuntala, was done by Britishers indeed during the Raj. For them, these texts were a gateway into understanding their subjects both for themselves as well as people back home in Britain. What followed, then, was an exhibition of Indian way of life from the perspective of prudish Christian and Victorian values. It is telling still, of Kalidasa’s talent, that Shakuntala reached far and wide in the West being adapted to various plays and operas in the past few centuries.

However, the modern audience needn’t be subjected to the Orientalism of 19th century Europeans and so, the English translator today would do well to capture Kalidasa as he intended himself in Sanskrit. This is what both Rao and Abhay K. have diligently worked towards, wanting to capture the legend in his element for the modern day lay reader. In fact, doing more of this would reveal not only Kalidasa to us but other great Sanskrit writers such as Bhasa, Bhartrihari, Bharavi, Magha, and Banabhatta, according to Abhay K.. Clearly, a world of boundless delight awaits, if we would only open ourselves to it.

(This article was first published by indiauntold on 31st Dec. 2021 and has been republished with author’s permission )

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.