New York City is everything you imagine it to be and more. There’s so much going on at all times that it can be both exhilarating and dizzying. I lived in Manhattan’s Riverside Drive area for about a year when I was studying journalism at Columbia University in 2015–2016. And one of the first things that struck me once I had settled into my new life was how the place was full of Yoga studios. Every other block had one, much like you would find momos wherever you go in Delhi.

I had never seen one back in India and the only time I had seen people practising Yoga was on random trips to the neighbourhood park. It was just old people doing it and it never seemed…interesting.

For my Master’s thesis, I was writing about mindfulness and a source had asked me to meet at Jivamukti Cafe for her interview. Located in NYC’s swanky Union Square, the place was essentially a Yoga studio with a cafe and a shop. People were filtering in and out of Yoga classes wearing their Yoga pants and while everyone seemed to feel quite comfortable with themselves, I had the distinct feeling of being out of place. I had no idea Yoga was *cool* now. What in hell was going on?

However, since then, I have discovered other things that are *cool* for white people:

- Ayurveda: I mean, even You’s (Netflix series) Joe Goldberg could feign interest in understanding Vata, Kapha, and Pitta to impress his girlfriend’s friends.

- Ghee: They can make serious effort at procuring this concoction that is supposed to be a health nightmare for those of us in India.

- Turmeric: Turmeric Latte, aka, the Golden Milk.

- Intermittent fasting and conscious breathing: Most of us would laugh if a “Whatsapp uncle or aunty” suggested there could be scientifically proven benefits to these but when white people, with all their self-importance, talk about it, we suddenly want to listen.

- Need I mention the late capitalism universe of Yoga again?

(A note: I use the term “white people” in this context because a lot of Indians really are quite conscious of the porcelain complexioned people. If it feels racist, sincere apologies but I have no other way to putting this because the term West is not all-encompassing for the problem discussed here.)

Not only are these “backward” things cool now, people across the world outside India are making insane amounts of money by propping them up. But most of us still don’t seem to have the courage to own up these for ourselves. Why is this the state of affairs when it comes to all things Indian?

Psychologically, if I tried to understand myself solely through someone else’s perspective, where would that leave the actual person that I am? After all, no one knows who we really are but ourselves. Which is why, spiritual practises stress upon self-knowledge and anyone who has applied themselves to it know exactly how evasive the self can be. You think it’s you but no, that was just some conditioning you picked up because you grew up in a certain environment. You grow up thinking that you are your anger, your insecurities, and your lack of self belief, but then you learn to sit in silence with yourself and watch the delusions wash away slowly and surely. And finally, the self begins to emerge. But get cocky and it will vanish away like smoke. It takes immense mental and emotional discipline to remain rooted in who you are.

Now replace the self with the nation. A collective self that is composed of a billion selves. Think about their collective anger, insecurities, and inferiority complexes. Think of the feeling of trying to walk in the dark that must envelop such a people. Think of how difficult it must be to still that collective self in order to understand it. The tragedy here is that we haven’t reached that point of psychological analysis as Indians yet.

Instead, we are still looking at ourselves through an outsider perspective. We still wait for the external validation to accept ourselves. We fight amongst ourselves when the validation does not look how we think it should look. Or worse yet, we question the outsider; why won’t you validate me? I am a 5000 year old civilisation, why won’t you accept my superiority so that I can get on with it too?

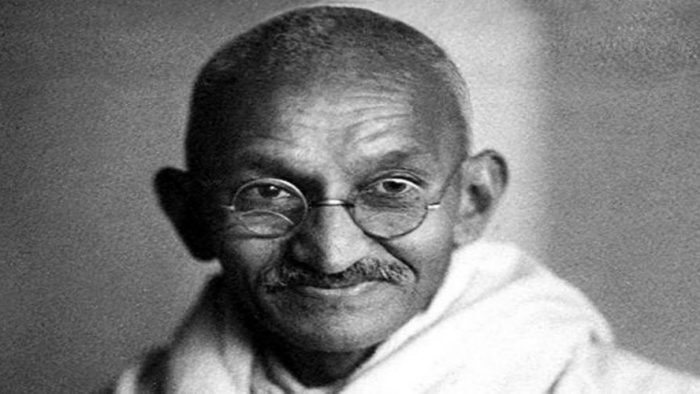

I used to think this was a post-independence colonial malaise. The Indians who grew up in a pre-liberalisation era didn’t have much going for India to feel great about and it didn’t help that the world didn’t think much of us either. Until I realised that this sort of psychological wiring existed in both pre-independence and post-liberalisation India. We already know how lost Indian millennials are but do we know how lost our political leaders were as well, Gandhi amongst them?

Does the psychology of the brown man who was offended at not being treated like a white man despite his white man clothes and demeanour in South Africa say something about us today? Or the fact that it was only after he was handed a copy of the Srimad Bhagvad Gita by members of the Theosophical Society that he dug into the text? Is it representative, then, that he should be the Father of the Nation for like him in the past, most Indians remain ignorant and lacking in self-belief of their civilisational heft and dig into it only after they feel validated by white people?

To be clear, this does not mean Gandhi is the problem but that he is perhaps the most striking symptom of the Indian inferiority complex. A century after he was born and twenty years after Indian independence, twenty year olds across India were asked how they understood India. Incidentally, I watched the video when I was 20 myself and remember thinking; the more things change, the more they remain the same. How curious that all these generations, born at different points of time and growing up in different versions of India, should feel unsure of themselves thanks to the same inferiority complex? How curious that we should all feel the same cluelessness about our civilisational inheritance.

Perhaps Ayse Zarakol explained it the best in her book, After Defeat: How the East Learned to Live with the West, when she wrote about countries like India, Turkey, Japan, and Russia. She described their trauma of losing wars, the collective amnesia around one’s civilisational heritage, and the shattered self-belief that accompanies that. She remarked, “Not being of the West; being behind the West; not being modern enough; not being developed or industrialised, secular, civilised, Christian, transparent, or democratic — these descriptions have all served to stigmatise certain states … that stigmatisation in international relations can lead to a sense of national shame, as well as auto-Orientalism and inferior status.”

Auto-Orientalism is definitely a phenomenon amongst Indians. To get a glimpse of that, simply look at the street photography by Indian photographers. The romanticisation of poverty is real but borrowed from our colonial overlords like Steve McCurry and a host of Nat Geo photographers. In fact, even the economist Kaushik Basu periodically feels nostalgic about the decaying Kolkata yet never seems to give up New York for it.

Coming back to self-analysis, understanding where and what you come from in this context is not about nationalism or chauvinism but putting the puzzle of you together. For instance, why is it that countless great thinkers of the West have struggled with the question of God, mortality, and sin, but not me, an average 20-something?

Might it have something to do with the multiple Hindu gods and goddesses, in addition to growing up around gurudwaras, churches, mosques, and more? Or the pervasiveness of the idea of Karma and the cycle of birth and death? Or those fantastical mythologies of deities being as flawed as humans, whether it’s a chillum smoking Shiva or a blood-thirsty Kali Ma? Or the epics that are full of entire range of human experience from Arjuna not wanting to fight with his family to Rama who let go of his wife because he felt his duty as a king was higher than his duty as a husband (i.e., professional over personal)? Does it have something to do with the fact that at the very core of it, there are no right or wrong answers when it comes to the Indian life?

For the national self to emerge, then, we need to look inwards rather than outwards. We need to be able to understand ourselves because we want to and not because someone made us feel good about ourselves for a moment.

And perhaps in doing so, we might have to re-evaluate the Father of the Nation, even if he is the most successful export of modern India. Both him and modern India need to be redefined so that we can come closer to the reality of the national self. And in doing so, let us allow the chips to fall where they may rather than desperately clutching at vestiges of external validation.

To add perspective to this, let me quote Carl Jung, the Swiss psychoanalyst, here, “The psychology of the individual is reflected in the psychology of the nation. What the nation does is done also by each individual, and so long as the individual continues to do it, the nation will do likewise. Only a change in the attitude of the individual can initiate a change in the psychology of the nation”.

We seem to suffer from a mental block when it comes to evaluating Gandhi. But that’s most bizarre because if we can question Rama, we must be allowed to question his bhakt, his devotee, the Mahatma. If we can ask why Rama abandoned his wife, we must be allowed to ask why Gandhi was such a terrible family man and had questionable personal practises. If we can question why Rama was duplicitous in killing Bali, we must be allowed to ask why Gandhi signed Bhagat Singh’s death warrant or played such a disastrous role in India’s partition, to name a few. There are countless questions to ask, let there be some honest answers now.

Allow me to end with a bit of Hermann Hesse here, “There is no reality except the one contained within us. That is why so many people live such an unreal life. They take the images outside of them for reality and never allow the world within to assert itself”.

This article first appeared on Medium and is reproduced here with the author’s permission.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.