Abstract:

Hastas or hand gestures have been an intrinsic part of the Indian classical dance technique and are used in various ways to convey meaning of the texts or narratives. The hands are limited by the radian of their movements but since we have five digits with various degrees of flexibility, the usages are unlimited.

This process of conveying meaning also means that the hand gestures are part of the world of rasa, which is a unique aesthetic experience in Indian Hindu art. This paper studies this gestural language through a multi-vector modal (Iriskhanova, Cienki, 2018) based on the bio semiotic approach. Till now gestures used in dance or sculptures have been studied in terms of technical texts, both natya and agamic in terms of conveying emotion and creating the rasa world. This paper argues that hastas are much more complex in the Indic system and have to be studied in a more holistic perspective which this multi vector model provides. This model offers the study of gesture kinesics or hasta chalana as a semiotic discipline which can be studied under a more practical and fundamental understanding of the underlying philosophies in the creation of these gestures and their usage.

Introduction:

Hastas in Indian classical dance have often been described as a ‘gestural language’ and have been used to present or enhance the padartha or bhavaratha or even the rasartha of the narrative in the performance. How are hastas and rasas connected in Indian classical dance traditions and are there any textual basis for the connection is being discussed in this paper? A direction connection is established in the Sanskrit manual Nandikeshwara’s Abhinaya Darpana. It has a shloka in the verse on Natya Krama which describes the purvaranga vidhi where instructions are given on how the dancer should perform. The verse ends with these lines:

यतो हस्तस्ततो दृष्टिर्यतोदृष्तिस्ततो मनः

यतो मनस्ततो भावो यतो भावोस्ततो रसः || 37||

where the hastas go there follows the eyes

where the eyes go there follows the mind

where the mind goes there follows the emotion

where the emotions go there follows the rasa

This is one of the very first and most well-known verses taught from Nandikeshwara’s Abhinaya Darpana which has for the better part of the 20th century and till date become a textbook for the southern Indian style of Bharata Natyam and is also a sourcebook for many other styles. This shloka connects the hasta prayoga or hasta chalana directly to rasottpatti or the creation of rasa. So for a practitioner of classical dance, this shloka is translated practically during practice and performance in the following manner. The dancer is constantly trained to look at the hasta and follow its progress when it is moving. Generally when it is stationary, the dancer also allows his/her eyes to be in a stationary position or sama dhristhi or a balanced glance towards the hasta. There are of course exceptions to this rule, where the eyes move in a direction which is opposite to, or in a different direction than the hasta, but eventually the drishti always connects to the hasta, either at the starting or the ending of a movement phrase. Interestingly even though the source of creating rasa in the Abhinaya Darpana is said to start with the hasta prayoga or hasta chalana, more often than not the face is at the center of discussions in rasa theory and the upaangas such as bhru (brows), chibuka (cheek), nasika (nose) puta (eyeballs) etc. are studied in order to master the creation of bhava and through that rasa. In the creation of rasa, the bhavas are the point of creation and the rasa drishthis are an important part of the training process in the Indian traditional dance or theatre. This focus on the face has in many ways sidelined the importance of hasta in the entire discussion of rasa in Indian aesthetics. Though the prayoga of the entire body in the creation of rasa is discussed in the shastras on natya throughout the ages, the question that arises is why did the hasta become the starting point at a certain period and became the focal point for the beginning of the creation of rasa, so much so that Nandikeshwara needed to emphasize its importance in a shloka. The answer to that perhaps lies in the previous shloka:

आस्येनालंबयेद् गीतं हस्तेनार्थ प्रदर्शयेत्

चक्षुर्भ्यां दर्शयेद् भावं पादाभ्यां तालमाचरेत् ||३६||

In this verse the artha or meaning is said to be conveyed or exhibited through the hasta. It is interesting to note that the verse doesn’t say anganam artha pradakshayet. Even if the entire body-mind is involved in the creation of rasa the central meaning of the word or shbada which is sacred in the traditional context lies primarily in the hasta prayoga or chalana. Hasta thus becomes a vital element in the delineation of rasa. Artha also does not necessarily mean just translating the meaning of the word into bodily movement, but it is also explicating the essence or rasartha or emotional meaning bhavartha and conveying it through the hasta.

Hasta Prayogas – exploration through a semiotic approach:

Exploring this further, the first question is what are the different classifications of usages of hastas? In the Natyashastra and the Abhinaya Darpana there are various classifications of the hastas such as single-hand gestures and double -hand gestures and their viniyogas or usages, the hastas or mudras for planets, relatives, devatas and for dance in general.

I have classified the typologies of gestures based on the viniyogas seen in the prayogas below, because the focus of the discussion is the artha or meaning which the hasta conveys or carries and eventually leads to rasottpatti. If one looks at the different viniyogas we can classify the variety of usages of hastas into the following types:

- Living beings and movements of both divine, human.

- Nature and movements/occurrences in nature – planets, animals, trees mountains rivers, lightning, waves etc.

- Conversational points and interactive actions between human beings.

- Conversational points and interactive actions between animals and other objects of nature.

- Highlighting the different expressions of the face and other parts of the body in conveying meaning or just for aesthetic appeal.

- Philosophical/religious concepts.

- Abstract ideas and emotions – either to highlight them or to show inner meanings.

- Inanimate objects and their movements – bed, chair, pen, crown.

- Hastas for enhancing the bhavas or rasas.

The above typologies indicate that hastas in the Hindu artistic/aesthetic context have evolved through centuries into a complex language system, and therefore the above types of hastas can be studied in a bio semiotic approach which is a tool used in language studies. Hastas are often referred to as a ‘gestural language’ and the linguistic models used in the language studies provide a good scientific/alternative method to study hastas or gestures with a bio semiotic approach which looks at the constitutive elements, typologies, mimetic constructs, iconicity, metaphors and other parameters. There has been now a major change in research methodologies where there is multi-modal trend of analysis employed in almost all areas and especially in linguistics. It has also been seen that even though a multimodal approach in understanding verbal communication is used, the linguists have given higher priority to the verbal component in conveying meanings even though gestural language and non-verbal cues also form a part of the semiotic studies for both historical and obvious reasons.

This approach has also been the case in understanding hastas used in Indian dance where analysis of the gestures has been more language centric because largely in the process of choreographing and understanding dance, the focus is on translating the artha of the shabda or spoken word or vac which is given a mystical, spiritual and historical importance in the Indian traditions. Even during the basic teaching of Indian classical dance, particularly the Bharata Natyam/Kuchipudi style, the focus is the padartha and shabdartha while training the students. The focus on the rasaartha is emphasised only at later stages or advanced training or even maybe left for the dancer /artist/choreographer to discover during their performative careers. Here I would like to clarify that rasas are taught with respect to the overall intent of a particular dance piece in the training process, but the focus on the rasartha of the hasta is very often not the focus of the learning and in some cases ignored completely. This training process has been very effective and to a large extent sufficient for the training and choreographing processes in Indian dance, and this also filters into the understanding and development of gestural language or hasta prayogas. Even in shastric manuals for dance, the hasta viniyogas are given in the following manner, for e.g. in the Abhinaya Darpana the viniyoga of Arala hasta will consist of shloka:

विशाध्यअमृतपानेषु प्रचण्डपवनेपिच ||114||

In practise, the dancer today learns the shloka and chants it showing the use of the hasta in practise sessions. The texts do not talk about the emotive content of the hasta or what rasa it is meant to convey. In practise and performance, the use of the hasta goes far beyond the uses stated in these texts and is more subject to the guru shishya parampara traditions. In this paper, I propose that understanding hastas at this level is sufficient for basic knowledge transmission but a deeper and more holistic approach will help the creation of more hastas and hasta viniyogas in the future. For example, one such area that has been studied and being explored in recent years is the comparative studies in hastas and yogic mudras.

There has been work done by many scholars and yoga experts on the common qualities of dance and yoga/pooja vidhis or rituals and one of the areas of research has also been the exploration of the common hastas or hand gestures. I will cite one example from my own studies. The most well-known hasta is the hamsasya and the arala mudra or hasta which is used in dhyana or mediation in both dance and in yoga.

Image: Arala and Hamsasya Hasta – Dr Siri Rama

It is also a gesture indicative of knowledge or teaching in dance. This movement of the fingers or the positioning of the fingers is sometimes referred to as hasta yoga or hasta krama. The body being the sum of its parts – the hand is also seen as being a reflection of the larger cosmic body (vastu purusha), which is constituted by the pancha mahabhutas or the five elements. The fingers of the hand are said to reflect the five elements –

- Thumb – The fire (Agni)अग्नि

- Index finger – The air (Vayu)वायु

- Middle finger – The ether (Aakasha)आकाशा

- Ring finger – The earth (Prithvi)पृथ्वी

- Small finger – The water (Jala)जला

There are 2 broad movement positions for the fingers:

- Urdhva ऊर्ध्व position – the fingers are held upright

- Vakrita वक्रित position – the fingers are bent There are several permutations and combinations within these two broad movement categories, where the fingers touch each other, or one finger wraps itself around the other fingers or sometimes when they are held far away from each other. In dance, these help in delineating meaning to lyrics of the music. But taking the earlier thought of assigning the nature of five elements to the five fingers one can assign a more layered meaning to the hastas. If one were to take any finger which is bent at the joints as symbolising control over the respective elements, the fingers which touch each other as the ones which interact or negate each other and the fingers which are held upright as the ones symbolising potential energy which can be made dynamic, we can postulate the following underlying meaning for these gestures. (Table 1)

TABLE 1

|

Hasta Name and meaning |

Fingers That touch |

Fingers that are bent |

Fingers that are held straight |

Metaphysical import |

Rasa |

|

Trishula |

Fire + Water |

– |

Air- Earth –Ether |

Three gunas supported by this mudra. Fire and water – two opposite factors negate each other and bring peace to the universe which is sustained by air –earth – ether. This is the symbol of Shiva somebody who is at yogic penance most of the time. |

Shanta – sthiratvam |

|

Mushthi (Fist ) |

All elements |

All are bent and in control |

None |

All fingers bent hence all are in control . This gesture is used to symbolize veera rasa in dance which requires a steady state of mind. |

Veera rasa – control of senses |

Challenges in this kind of semiotic analysis can be overcome if both practitioners and theoreticians in the shastric traditions can work together to understand the hidden meanings and metaphors of the hastas in creating the rasa loka. This analysis can broaden with the help of the methodology suggested ahead. The following model based on linguistics could be one way of analyzing the hastas, their function in the world of rasa and transitions which have taken place over centuries.

Multi-vector model for analysis and understanding of hastas:

The universally accepted definition of gestures is that it is an action that counts as “attempt to give information of some sort“ (Kendon 2004:7). A study of these informative gestures in linguistics has been part of semiotic studies and are now recognized as ‘signs’ which fulfill meaning that is intended to be conveyed. Some have even argued that they can have syntax, morphology and can even form a lexicon ((Irishkanova and Cienki 2018:28). The scientific understanding of gestures in cognitive linguistics has moved from being just considered as a sign like but considered as a “signs in a variety of ways” (Irishnkanova and Cienki, 2018:30). This leads to a multi-vector modeled analysis of gestures and the vectors suggested by Irishkanova and Cienki (2018) and I find that these gesture vectors could be useful for studying the complex nature of hasta prayogas or usages in Indian dance.

1. Conventionality –entrenchment of form and meaning; for example the ashirvaada or blessing gesture (Pataka hasta).

2.Semanticity – whether the gesture conveys any meaningful messages. For example, the mukula gesture changing to alapadma which conveys blooming of a flower.

3. Arbitrariness – the absence of form meaning association. For example swatting away somebody’s touch with a pataka gesture.

4. Pragmatic transparency – the explicitness of pragmatic intentions for the interlocutors. For example in Indian classical dance performances, the Anjali or namaskara hasta performed at the end of a dance piece helps to indicate to the audience that the dance has reached its ending

5. Autonomy – whether the gesture can be shown without its verbal accompaniment and still be used and interpreted. For example the gesture of playing the veena with two mrigashirsha hands can be used to show playing music even if the words in the accompanying compositions just says sangeeta or music in general.

6. Social and cultural import – gestures that are directly relevant to certain rituals in society. In the Indian classical dance context, sampradaya and changes in sampradaya are a huge factor in the use of hastas whether they are margi or desi traditions. This has to be factored into this graph and understanding of hastas. For example, the touching of feet or charanasparsha which is indicative of respect and obeisance to gods or elders or gurus or respected people.

7. Awareness – is the signalling of meta-communicative awareness of producing a gesture. This is particularly relevant to the creation of rasa as the dancer is aware of a certain gesture which indicates beauty or love.

8. Recurrence – repetition of gestures to fulfill a certain function. For example, repeating of a wavelike movement in pataka hasta to create a water effect but to show a larger water body like the sagara or ocean.

9. Iconicity – gestures showing certain iconic cultural images or certain characteristic features of the icon or object. For example, the Nataraja hand gesture or the pataka hasta to show cutting down an object.

10. Metaphoricity – to be able to show abstract entities. For example, the gesture of infinite time shown through the movement of the hamsasya hasta.

11. Indexicality is the use of a gesture to show some entity in the vicinity or within a construed frame. For example, the showing of a sakhi or friend through hamsapaksha hasta.

12. Salience – whether the gesture is the focal position for a multimodal usage event. For example, when Krishna tends to the cattle – the simhamukha gesture showing the cow becomes the focal point of the entire dramatic sequence.

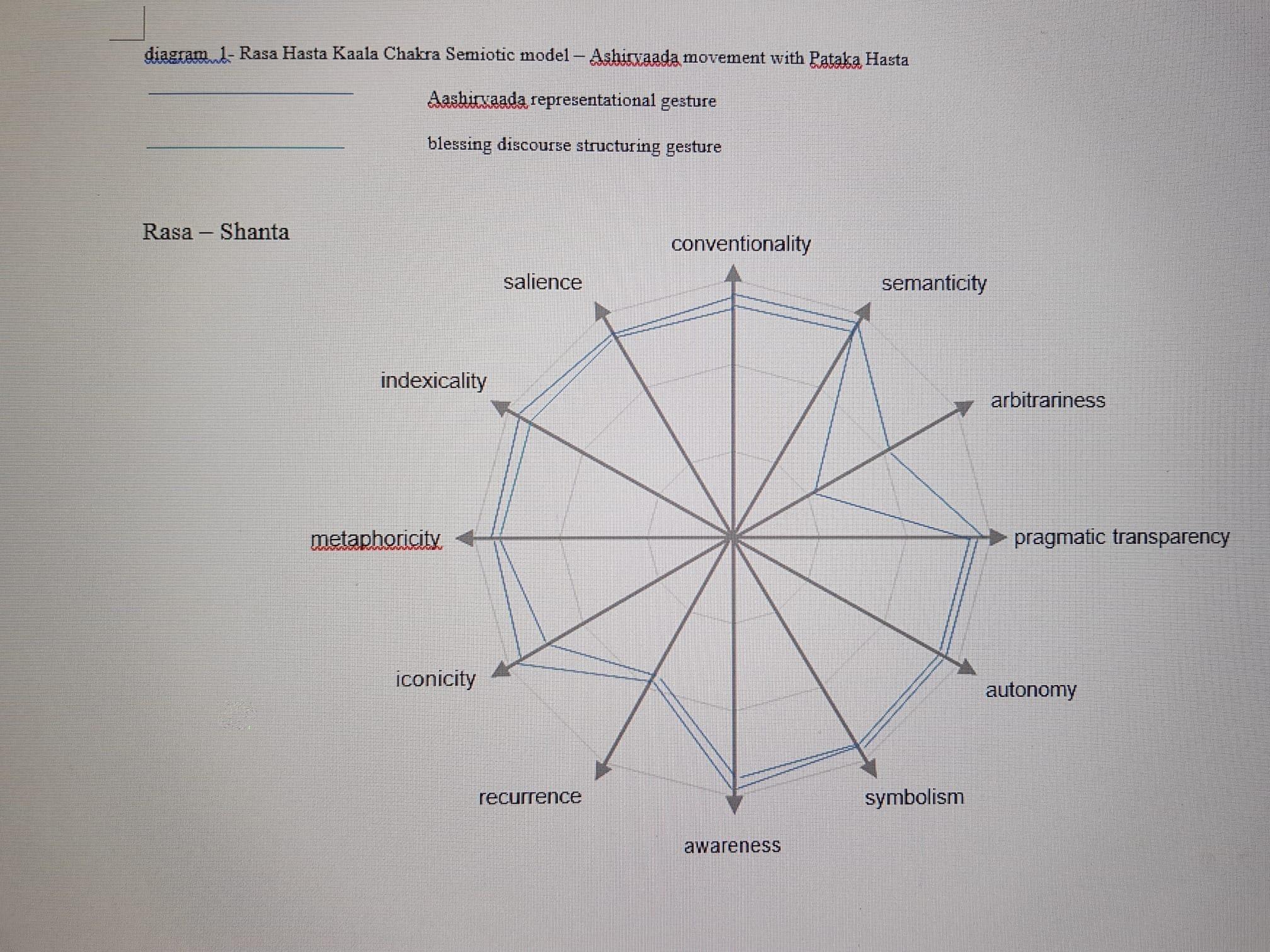

The vectors suggested by Irishkanova and Cienki (2018) to analyse gestures could be a useful model to analyse hastas, performance practices, archive and even help in creation of new hastas. The vector model can be sketched and offers a visual understanding of the complexity of the subject of hastas and their importance in the world of rasas. I have applied the vector model in the above-mentioned paper to the pataka hasta usage in dance as a blessing gesture or aashirvaadakriya used in many instances in dance when dramatizing events or even when showing divine blessing. (Diagram 1 )

Diagram 1 shows a vector extending from the centre point and the reason for choosing a vector is also to indicate the limitless possibilities of a particular gesture and also to indicate the movement potential/intensity of the gestures. There are 3 levels to the grid which indicates three possible intensity levels for the gesture and since it is subject to semiotic interpretations, the boundaries are blurred rather than specific. Considering the representational gesture, the blessing gesture is very iconic in nature and has a high degree of semanticity, conventionality, salience, indexality, metaphoricity, autonomy, symbolism and pragmatic transparency (clarity as to its intention). It has lower degree of recurrence and is not arbitrary, as the ashirvaada gesture has to be used in discretion even in dance. The dramatic discourse structure as affected by this gesture is high in all areas except in recurrence and arbitrariness. I have placed this graph in the three-dimensional plane of rasa, because time and space are significant factors in the usage of and understanding of hastas. So, the rasartha or rasa mandala of the ashirvaada gesture can be understood as shanta, with the ashirvaada kriya creating the ambience of shanta along with the other bhavas and abhinaya modes. The various vectors can be explored further and qualitative perspectives can be signified. For example, the symbolism of the pataka hand gesture can be understood in terms of the panchatattva seen earlier in this paper.

In conclusion, seeing how the hasta has a direct connection with the creation of rasa, the multi-vector model used in the cognitive linguistics discipline is a wonderful tool to archive and analyze hastas. This holistic approach has always been the basis of ancient Indian traditions where the development of a gesture in classic traditions has always been a result of a philosophical semiotic and cultural understanding and approach to creativity. The influence of tantric doctrines, agamic principles, yogic influences, temple and court traditions of dance have resulted in the creation and practice of hastas. The approach of learning the padartha and meaning was probably sufficient in the past for practitioners and rasikas of dance as the society was more homogenous and the gestural import of these hastas and their viniyogas was obvious. In today’s world, however where there are various cultural influences and more hybrid societies, the meaning and scale of the hastas need to archived and understood in more detailed and scientific way as informed by the Hindu rasa aesthetic theories.

Conference on Hindu Aesthetics

Watch video presentation here:

Selected References:

- Iriskhanova, O. K., & Cienki, A. (2018). The semiotics of gestures in cognitive linguistics: Contribution and challenges. Voprosy Kognitivnoy Lingvistiki, 2018(4), 25-36. https://doi.org/10.20916/1812-3228-2018-4-25-36

- Kendon. (2004). Gesture: Visible Action as Utterance. Cambridge University Press.

- Nandikeśvara, & Dādhīca Puru. (1988). Abhinaya darpaṇa: mūla evaṃ Hindī kāvyānuvāda. Bindu Prakāśana.

Image Credit: Nisha Sharma Dance ki Baat

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.