Introduction

The Hoysala dynasty of Karnataka built several artistically magnificent temples in the Vesara style, which have ornate sculptures and reliefs depicting the trinity (Shiva, Vishnu and Bramha), several divine figures and scenes from ordinary life from the medieval period. Detailed study of these sculptures and reliefs shows that an entire legacy of visual art dedicated to the feminine principle or Shakti, have also been artistically rendered by the sculptors of that era. Though many temples are dedicated to Vishnu or Keshava and Shiva or Hoysaleshwara, both the outer walls and the inner mandapas are carved with many sculptures and reliefs of dancing Shaktis, apsaras, yoginis and common folk shown in nritya or dancing postures. This unique contribution and its iconography will be discussed and highlighted in the paper in the light of sacred and secular aspects with reference to natya and Shilpa shastras. The focus of this paper will be to examine the different aspects of sacred and secular in the dance sculptures of the feminine representations in the Hoysala temples and their placement in the architecture of the temple. The placement of the sculptures and their size also determines the narrative and philosophical import of divine ‘feminine’. The objective of the paper is to bring attention to the use of movement by the sculptors to explicate the cosmic plan of the temple and the philosophical canons of the period. The research was carried out in field visits to the temples, and studying both the qualitative and quantitative aspects of the sculptures under study in the larger architectural ‘plan’ or Vaastu of the Hoysala temples. This paper will consist of research findings about the dancing goddesses (Lakshmi, Saraswati, Parvati), the myths of dancing Lord Vishnu’s in his feminine aspect as Mohini and other dancing female depictions in sculptures and reliefs of Hoysala temples.

Brief note on the history and structure of Halebidu and Belur temples

1. Halebidu

History

In the medieval period, between the 10th and the 14th c. AD, the Hoysala rulers of Karnataka built many beautiful temples in and around Halebidu in Karnataka. This area has been known historically as Dvarasamudra or Dorasamudra. The Hoysaleshvara temple, though partially ruined, stands as a splendid specimen reflecting the art and architectural style of the Hoysalas. Daily rituals to the deity Shiva have resumed only recently, and the temple is still largely known for its economic value as a major tourist attraction. The Karnataka government’s archaeological department now maintains the temple. An inscription in a nearby village states that this temple was constructed for the Hoysala King Vishnuvardhana by his army chief Ketamalla, and he in turn granted some lands for the temple in 1121 AD. The Hoysaleshvara temple has several folk tales or dantakathas associated with it. The best known story is as follows. Indra, the king of the Gods, became very jealous of the fact that Dorasamudra, the Hoysala capital, was more beautiful than his capital Amaravati. He realized that this was because of the perfect construction of the Hoysaleshvara Shiva temple. So he decided to mar its perfection by carrying away its vimanas or towers. There are minor variations to this tale, which recurs in local tourist literature.

Structure

The Hoysaleshvara temple is a dvikuta structure or a temple with two central shrines, and is constructed in the Vesara style. The Vesara style combines elements of nagara or northern and the dravida or southern styles of traditional architecture. The outer walls of the temple are carved in an ornate and intricate pattern which is a characteristic style of Hoysala temples. The temple stands on a jagati or platform and there are bands (pattikas) of decorative motifs, gajas (elephants), hamsas (swans) and other scenes of human endeavour carved in exquisite detail on the lower levels. The middle section of the temple is where the prominently carved sculptures find a place of honour. Each projection or recession has one large sculpture placed in the middle section of the temple wall. Some of these are of individual deities and some sculptures have deities with their consorts (for e.g. Lakshmi with Narasimha or Varaha with Bhudevi).

2. Belur

History

Very little is known about Belur before the advent of the Hoysala dynasty. In c.1100 AD with the Hoysala king Ballala I, Belur grew in importance and it continued to prosper under his brother and successor, Vishnuvardhana. In some of the inscriptions it is known as earthly Vaikuntha or the abode of the God Vishnu and is also referred to asdakshina Varanasi. In commemoration of his victory against the Cholas in Talakadu in 1116 AD, Vishnuvardhana built several temples and the most famous among them was the Chennakeshava temple at Belur, which was consecrated in 1117 AD. An inscription records the event of consecration of the temple by Vishnuvardhana, and even today the hymn in praise of the presiding deity Chennakeshava has the words “the one who is worshipped by Vishnuvardhana” or Vishnuvardhanapujita. Ever since the temple of the Chennakeshava was built at Belur, the fortunes of the temple and the town have been indivisible.

With the fall of the Hoysala kingdom in the fourteenth century, Belur, which had gained the status of a pilgrimage centre until then under the Hoysalas, lost its importance. Later it regained some of its glory under the Mysore Wodeyars rulers in the seventeenth century. In the intervening period in the fourteenth century Halebidu, a sister town, also known as Dorasamudra (Dvarasamudra) was destroyed by the Vijayanagara invasion, and in the process Belur which was included in the province of Balam was given to the Vijayanagara kings. The fifteenth century saw Belur pass through the hands of the Vijayanagara King Sriranga Raya III to the Ikkeri dynasty. Later Belur was taken in 1690 AD by the Mysore Wodeyar ruler and fell under his jurisdiction till India became independent in 1947.

Structure

The Belur main temple is built in Hoysala style with chlorite schist, which is favorable for delicate carving, detailed work, and also takes polish and lots of modulations. As is characteristic of many Hoysala temples it stands on a raised platform (3ft in height) measuring 178 ft by 156 ft. The platform is wide and follows a star shaped pattern. It serves as a pradakshina patha around the temple as there is no place for pradakshina around the garbhagriha within the temple.

The main temple that stands above this platform can be divided into two major sections. The front section which one encounters first on entering includes the navaranga and the mandapa , and the second section includes the vestibule or sukhanasi and the sanctum or garbhagriha

Aspects of the feminine represented through dance at Belur and Halebidu – divine and secular

I will begin my discussion with the Belur Chennakeshava temple and there are various legends associated with the temple. One of the purana/legend/myth is connected with dance and the other legend is that of the sculptor who was associated with the building of the temple. In this paper I will focus on the dance aspects of the sthala puranas.

The Mohini legend

The presiding deity in the temple is Vishnuwho is said to be in his incarnation as a beautiful divine female – Mohini and hence he is called Chennakeshava or the beautiful Keshava. The myth is described in Sivalilamrita as follows:

Shiva blessed Bhasmasura, with the ability to burn anybody on whose head he placed his hand. Bhasmasura in his arrogance proceeded to try the boon on Shiva himself. Shiva then ran fearing for his safety. Vishnu in the guise of Mohini then intervened. Mohini places herself in the path of the demon and he gets enchanted by her beauty. He asks her to marry him. Mohini refuses and says she would marry the man who could defeat her in a dance contest. Bhasmasura agrees and the contest begins, with Bhasmasura mimicking Mohini’s movements. Mohini cleverly takes a pose in which she places her hand on her head. Bhasmasura does the same and falls prey to his own powers, and he is burnt to ashes. As part of the utsavas or festivals conducted in the temple in the month of April, the legend of Mohini Bhasmasura is reenacted even today in the north – west corner of the temple, with the Keshava image dressed as Mohini.

This festival is called the Mohinialankarotsavaor the festival where the God in his Mohini decoration or alankara is worshipped. In this the Keshava utsavamurti (the image used for such festivals) is dressed up as Mohini. A symbolic statue of Bhasmasura, is burnt, in the evening and while burning the Bhasmasura statue the Mohini statue is made to sway. The festival begins with a shloka which praises Keshava as bhasmasuradhvamsakam.

This festival over the years has been combined with the festival of Manmatha which occurs at the same time. There is a parallel between the two legends- with the main protagonists being burnt to ashes. But the similarity ends here. In this festival called Kamanahabba and an effigy of Manmatha is burnt and it is celebrated all over Karnataka. The effigy that is constructed out of old wood and other objects stolen from houses in the neighborhood by young children is then burnt. The priests in the temple call the same festival Mohini alankarotsava and the local people call it Kamanahabba. One of the reasons for this might be that the legend of Mohini- Bhasmasura lost its importance and the more popular festival of Manmatha came to be celebrated. How does this translate into the shilpas carved on the temple walls? Here the topic of the famous madanikas or shalabhanjikas of Belur is of importance.

(The bracket figures or the madanikais of Belur have long been the topic of scholarly discussion and interest. It is interesting to note that there is one theory that they were added to the temple after its completion (Collyer, 1990). However, there are no epigraphic records to substantiate this view, but the analysis is based on stylistic grounds as these images bear close resemblance to the sculptures at Halebidu which were carved later (c.1127 AD). On close observation I found smaller bracket figures, which seemed to be the original bracket figures. These are shorter in height and not carved in the round and even the craftsmanship is very poor. The now famous madanikais are placed over these older figures and conceal them. However, in places where the madanikais are stolen or lost the older bracket figures can be seen. So I would tend to agree with Collyer’s view that the newer madanikai figures were added much later, and are probably closer in terms of style to the Halebidu figures. )

Many of these madanikais have the name of the sculptor signed at the bottom of the figure and all of them are approximately three feet in height, which is a very important part of the Hoyasala legacy. There are forty bracket figures supporting the eave on the outside and four bracket figures inside. The four additional madanikaismadanikai figures are placed in the mandapa of the temple. Collyer (1990) says that since they were placed in a less significant part of the temple they were not bound by the strict representational rules of iconography and hence the figures are a result of the individual sculptor’s imagination and style. Sastri (1965), however, says that the stambhas (pillars or columns) in a temple represent the stambha purusha who carries the vimana on his head. By this statement he means that the pillar is visualized as a human who is carrying the tower of the temple. The madanikais on the sthambas touching the vimana represent the presiding deity. Though some are secular in nature they represent mandalarahasya (Sastri, 1965). This argument is substantiated by the sthala purana. According to the sthalapurana, Vishnu took the form of Mohini in Belur and hence Vishnu’s kanyarupa is seen in the madanikai images.

The different types of bracket figures are given below. Many of the motifs are repeated.

I find three different categories of figures, and they are:

Type I – consisting of popular visual motifs such as lady admiring herself in the mirror etc.

Type II -– consisting of dancers and musicians who are also shown dancing

Type III -– consisting of divine figures.

For this paper I will refer only to those that are specifically in dancing postures.

In the categories mentioned above the shalabhanjika nartaki – the dancer, falls in type II. This damsel has extended her right hand above her head with her left hand held at her waist. Her left leg is raised with her right leg bent slightly to take her body weight. She is accompanied by drummers. There are two more bracket figures of dancers in different poses. One of the dancers is accompanied by a lady who is also singing and dancing. The artist Chavana, son of Dashoja has carved this sculpture. The third figure of a dancer has an inscription identifying the sculptor as one Nagoja of Gadag. The inscription is as follows,

Srimatugaduginasvyambhutrikuteshvaradevaravidyavantasujanajanamanoranjanasaraswatipadmabhojaruvarijagadalakatojanaputranagojanahastaikaushalamangalamahashri

The inscription describes Nagoja son of Katoja of Gadag who was the artist of the God Svayambhu Trikuteshvara of Gadag.

This figure because of the pose of one hand being held above the head is often referred to as the Mohini shalabhanjika, though the inscription does not mention any name for the sculpture, and there are no images of Bhasmasura shown next to this sculpture. So the myth of dance remains an oral tradition and is not seen in any of the sculptural reliefs around the temple. This dancer (fig 1) has been described as having the nupurapadikachari and uromandalahasta by Vatsyayan (1968). This same gesture is referred to as urdhvajanu pose by Nadig (1990). The nupurapadikachari is described as one where the foot with the toes raised or ancita foot is lifted up, taken behind another foot and then made to fall on the ground. Vatsyayan obviously sees this figure as the first part of the chaari, whereas Nadig assumes that this leg movement is the beginning of the urdhvajanu movement in which the leg moves higher. The nartaki is accompanied by a male dancing drummer to the right and a flautist and cymbalist on the left.

FIG 1

The next sculpture (fig 2) has the ayatasthana, that is specified for women in the Natyashastra. Unlike the many other examples this figure does not hold any instrument. The fact that the same positions of the feet are used both when playing on an instrument and when a dancer is shown is significant. This confirms that the stance was not merely used as a stylized pose for musicians, but was also used to represent a regular dance movement or posture. The musicians shown earlier in this posture can also be considered as dancing figures.

FIG 2

The left hand is lifted above the head in patakahasta and the right is in dolahasta. Accompanying the nartaki is a dancing male drummer and a seated male cymbalist.

Halebidu

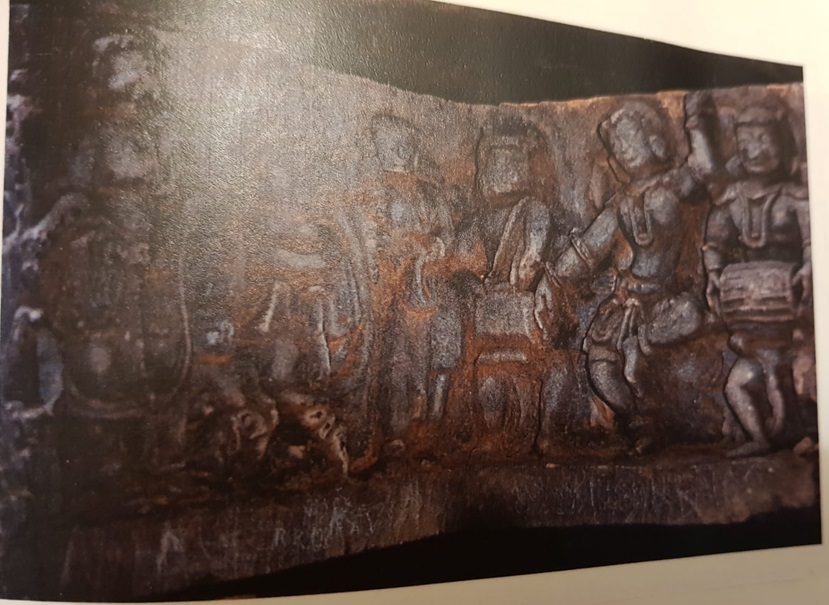

Now I will consider examples of female dance figures found in the band of narrative friezes at Halebidu. I have selected examples based on location and movement, in addition to some which illustrate the position and movement of the female figures with respect to their neighboring figures. Some dance figures are located in recessions, in manner similar to the larger figures in the upper sections. This does not seem to have made a difference in the nature of movement depicted, but the sculptor has used the corners to show interaction between the musicians and dancers. For example to the left of fig 3, a drummer is placed facing the dancer, which uses the recession to increase the interaction between the drummer and dancer. Similarly, to the extreme right a spectator is placed facing the cymbalist and drummer accompanying the dancer.

FIG 3

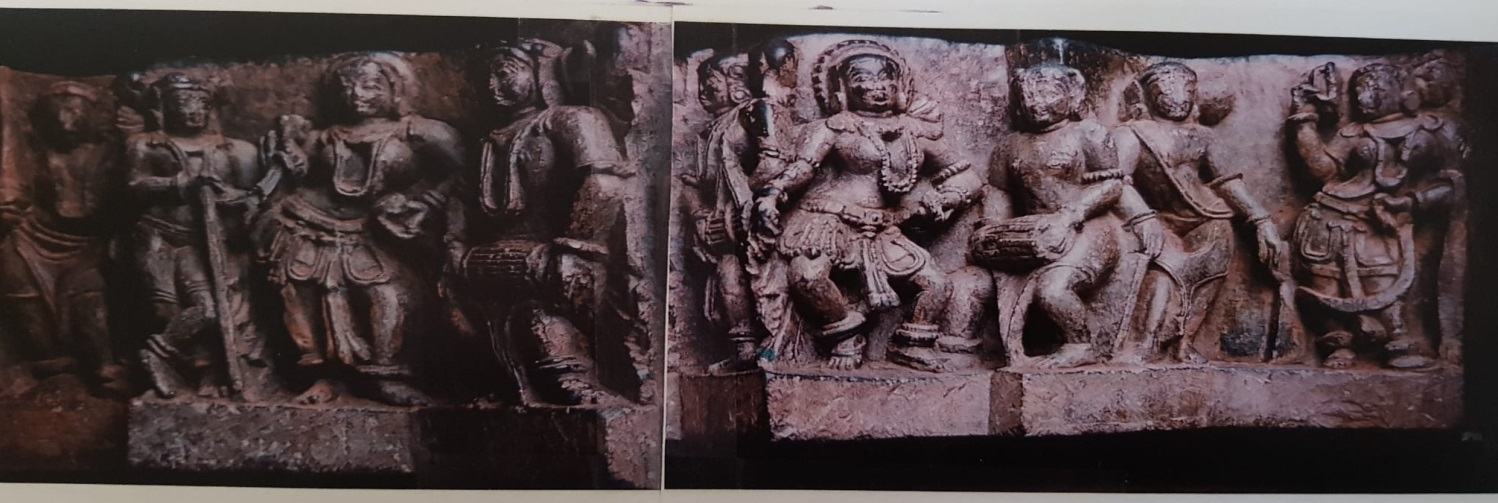

Fig 4 shows three ensembles placed in series.

FIG 4

Beginning at the left two drummers look on as a dancer performs to the accompaniment of a flautist and a cymbal player. The next ensemble has a vina player, flautist, a drummer and a cymbalist accompanying the dancer. They all are shown looking at the dancer. The third corner has a dancer accompanied by a drummer, cymbalist and flautist. The dancers are shown in different poses which in addition to affording relief to the eye also makes sculptures appear mobile. The movements are the familiar urdhvajanu position and ayatasthana with bent knees. The hands of all three are raised in the alapallava gesture or the vismaya hasta and the other hand is held out in the lata hasta or dola hasta. These poses have been seen in earlier in the larger figures in upper sections. It appears as though the sculptors at Halebidu have limited themselves to few variations in dance movements. The oft repeated movement is the urdhvajanu position and the other stance is the ayatasthana.

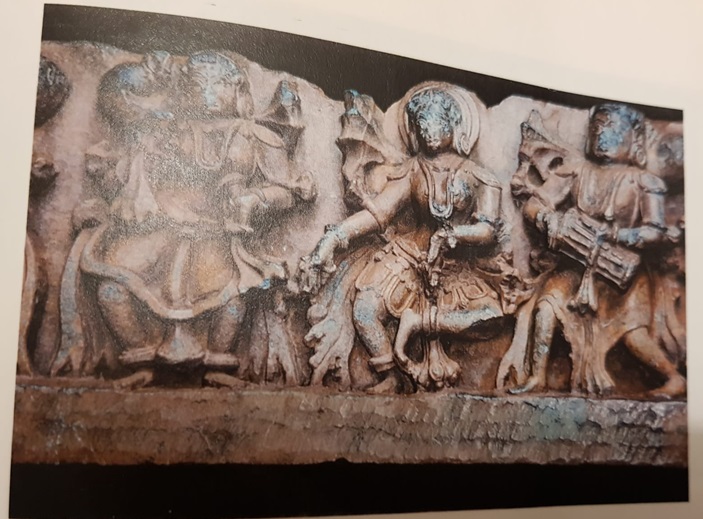

Taking the urdhvajanu position of the central figure, I will now consider other examples at Halebidu, which show variations in the same movement. Fig 5 shows a dancer in a similar position accompanied by dancing musicians.

FIG 5

In fig 6, the dancer has lifted her leg higher and has added a bend to her torso and head, which makes the pose more graceful than the more static nature of the earlier figures.

FIG 6

Fig 7 provides a new hand position.

FIG 7

The hand is held above the head, and the fingers appear to be held in a hasta which is unclear because of the badly weathered stone. Another variation of hands is seen in the next image (fig 8).

FIG 8

The left hand is held near the waist with the palm facing upwards. Another figure (fig 9) shows the hand held gracefully at waist with the wrist bent and fingers pointing to the ground.

FIG 9

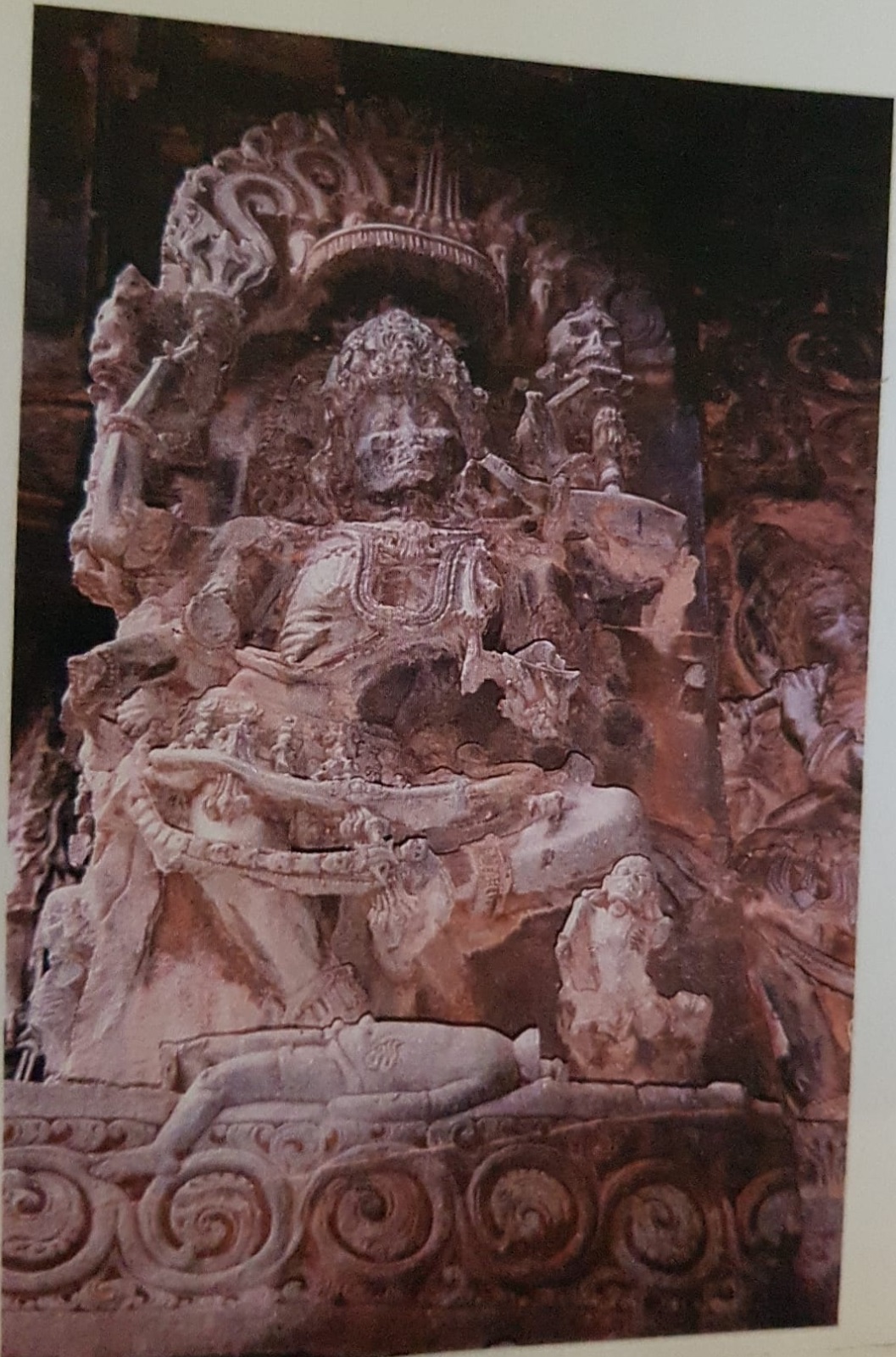

The next category of dancing figures is are the dancing divinities which fall in the Type III classification mentioned earlier.

Belur

Among the shalabhanjika figures there is a dancing Durga (This is the popular name for the figure which is obviously a Shaivite divinity) (Fig 10). Here the dancing goddess has a skull and a trident in her hands accompanied by two drummers . There is an inscription below this

BalligaameyaruvariSashojamaadidasalabhanjike

which translates as the shalabhanjika made by the artist Dasoja from Balligame. It is interesting that the only place where the madanikai figures are identified as shalabhanjikas is an inscription which is etched under the figure of a goddess shown dancing. The goddess, however is shown with a trishula in her hand and Rao (1981) has identified her as Durga. The inscription the sculpture identifies what is obviously a Shaivite goddess as ashalabhanjika.

FIG 10

Halebidu

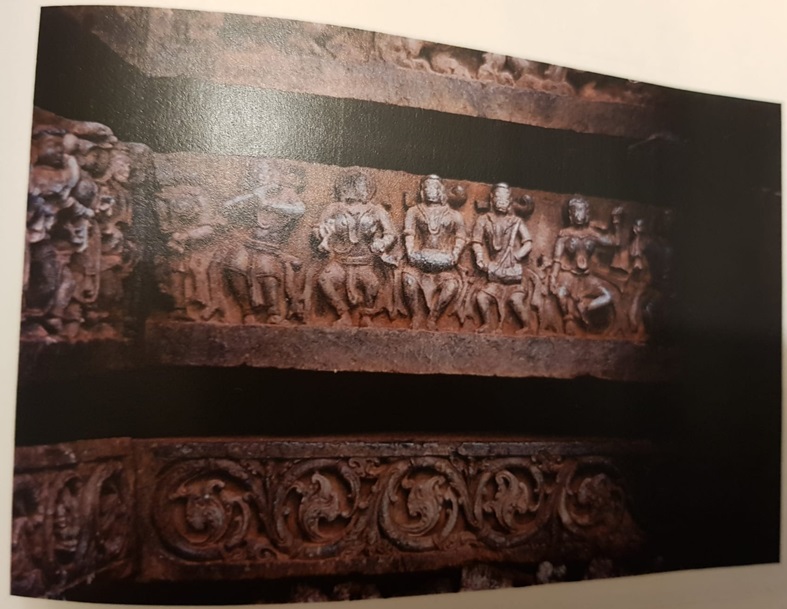

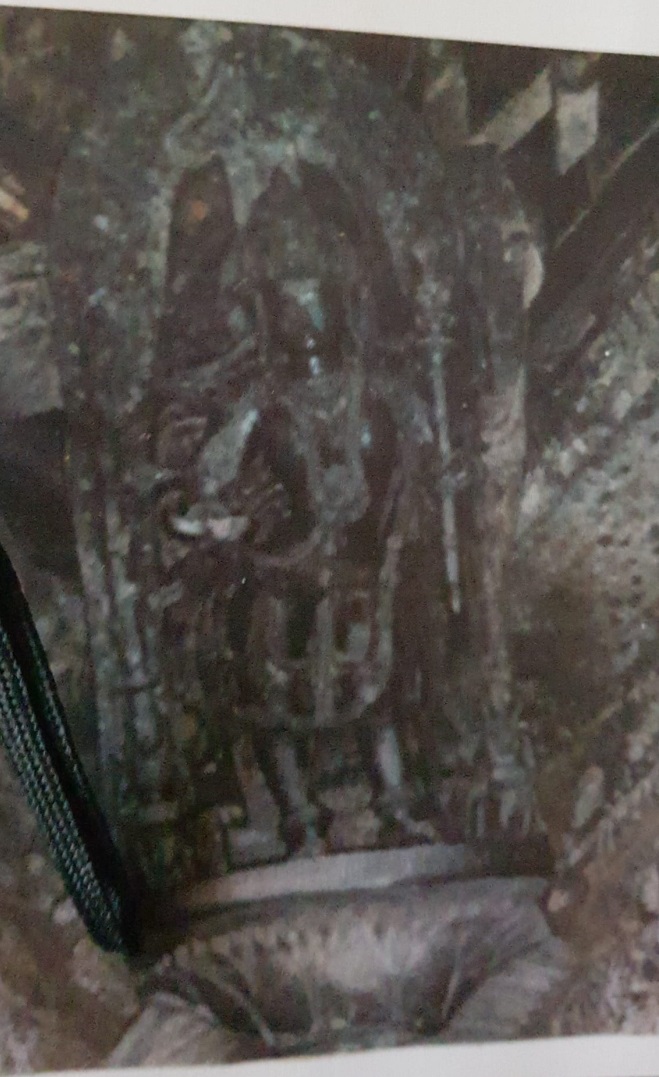

While studying dance sculptures at Halebidu a startling and fascinating aspect of a band of large sculptures above the jagati and carved on the outer walls surrounding the sukhanasi and grabhagriha of the temple. This is the depiction of dancing Shaktis, which I discovered during my doctoral studies. These dancing Shaktis are carved in intricate detail on the outer wall of the main temple and one can see them when one takes a pradakshinapatha or circumambulatory path around the temple.

During my doctoral studies I was focused on the Vishnu and Shiva dance sculptures, as my thesis aimed at comparing the Vishnu or Chennakeshava shrine at Belur with the Shaiva Hoysaleshwara temple at Halebidu. For a long time the significance of the position and placement of the dancing Shaktis was not apparent. It was only when I studied entire sections of the temple that I realized that the placement of the dancing Shaktis was very important and deliberate. A third interesting feature is that the dancing Shaktis are not just Shaivite figures as one might expect in a Shiva temple. Lakshmi and Saraswati are also depicted in dancing modes next to their consorts.

I realized that these Shaktis were placed near their male counterparts i.e. Parvati near Shiva, Lakshmi near Vishnu , Sarasvati next to Brahma. This is not immediately apparent as the sculptures are carved on sections which are not one flat panel but are on a star pattern in which the sections face in and out. Only when one photographs these sections and sees them laid out on a flat surface the placement of these sculptures becomes evident. What is even more fascinating is the fact that dancing Shaktis are placed next to their consorts, who are often in static position (or samapadasthana) and one also speculates as to why both the deity and his consort were carved on separate sections. As is well known in the Nataraja iconography it is Shiva who is dancing and his consort Shivakamasundari is standing by his side and watching. At Halebidu the dance motif seems to be reversed with the Vishnu, Shiva and Brahma standing and the consorts or Shakti’s, Lakshmi, Parvati and Sarasvati shown dancing. It is interesting that though Halebidu is a temple dedicated to Shiva, there are almost as many images of dancing Goddesses as Shiva himself. We can just speculate based on the religious leanings of that period that that these dancing Shaktis grew to be a very important part of the local religious milieu.

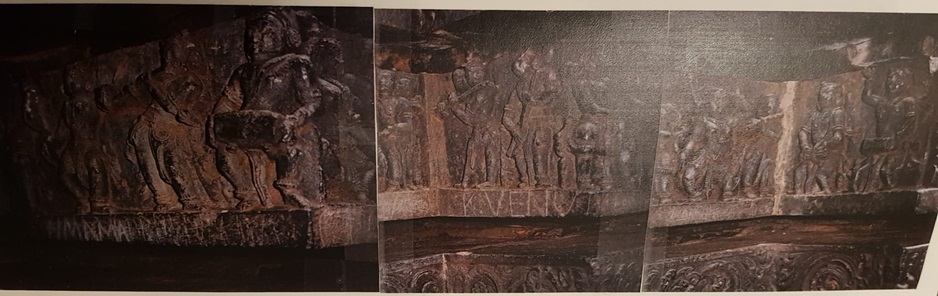

An in-depth study of the many different Shaktis revealed some iconographic patterns. These have been collated below. At Halebidu, we see Goddess Saraswati (fig 11) dancing (NatyaSaraswati) with pasha (noose) , ankusha (elephant goad), japamala (rosary beads), sruva (sacrificial ladle or a spoon), vedas, padma (lotus), vina, venu (flute)and phala (fruit) in her hands. She is usually accompanied by a hamsa (swan) and drummers. The Goddess stands with her feet in the urdhvajanuchari position- in this movement the legs are bent with one leg lifted at the knee.

FIG 11

Goddess Lakshmi (fig 12) is seen dancing with ankusha , pasha ,phala, padma and kamandalu ( vessel for holy water), and the flower – nilotpala. Her hands are in vismaya (surprise) or alapadma and dola or latahasta. She is usually accompanied by Garuda and drummers. Her feet are always in the urdhvajanuchari position.

FIG 12

Goddess Durga (fig 13) who is shown dancing usually holds the sarpa (snake), damaru (small hand drum), patra (bowl), kapala (skull), trishula (trident), padma, phala, nilotpala and khadga (sword). Some unusual objects also are seen , like the khatvanga (club), a castanet like object, and veni (braid). Her hands are held in the vismaya and /or latahasta. She is sometimes accompanied by a mongoose, and always accompanied by devotees and/or bhutaganas who are shown dancing, or drummers. She is shown in urdhvajanuchari position and sometimes in the ayata position which can be described bent knee plié position or a rechita position.

FIG 13

Another interesting sculpture is that of dancing Chamunda (fig 14) who is shown in the ghorarupa or fierce form with a skeletal frame. She is shown holding the khadga, damaru, kapala, trishula, ghanta (bell) and sarpa. She is usually shown shown holding the banahasta or latahasta or vismayahasta. She is always in the urdhvajanuchari position and accompanied by skeletal devotees. This dancing Chamunda sculpture is part of the saptamatrika reliefs in other temples and this emaciated form is usually shown at the end of the saptmatrika panel. It is indeed interesting to see this depicted here at Halebidu, and shows strong influence if tantric shakta traditions.

FIG 14

This repetition of sculptures and reliefs shows that there was a definite iconographic pattern followed by the Hoysala sculptors for depicting the dancing Shaktis. The different sculptures of the three goddesses hold similar attributes and are shown in particular dancing modes.

After close observation and a quantitative analysis of dance sculptures during my doctoral research I found that there are more sculptures/reliefs of dancing Shaktis than those represented either standing or sitting. This could be a visual interpretation of the Goddess representing dynamic creative energy and the temple as a mandala which through its rituals invokes the cosmic mandala within its architectural plan. The religious leanings of the period i.e. Shri Vaishnavism also point to the fact that Lakshmi or Shri in the Shri Vaishnavism of Saint Ramanuja grew in importance during this era, with very well-known historical records of the Jaina King Bittideva at the urging of Sri Ramanuja taking to Sri Vaishnavism and changing his name to Vishnuvardhana. In Saint Ramanuja’s and the Pancharatra philosophy, Shri or Lakshmi is often described as the embodiment of the power of compassion of Lord Vishnu. The mother Goddess was on par or at least next in hierarchy to the Supreme godhead Vishnu. Shri enacted the Shakti or power of Lord Vishnu and there are teachings where Lord Vishnu is viewed as the supreme actor and Sri or Lakshmi is the one doing the acting. Thus, a combination of influences due to the religious leanings also might have prompted the growth of the dancing Shakti iconography. The Hoysala style Lakshmi temple at Doddagadavalli (which is very close to Halebidu), and inscriptional evidence of several other temples, also shows that worship of the Goddess was a very important local tradition. The Goddess as visualized in her dancing image, is perhaps an indication of Shakti being in constant movement, and the oscillatory aspect of the dynamic universe being represented through her dance. The sculptural representations of the dancing Goddess indicate the importance of the Goddess and shows that movement was a very important aspect of the Hoysala sculptural style. The sculptural representation of dancing Saraswati inspired me to conceptualise a solo Bharata Natyam presentation on Goddess Sarasvati titled Sakala Kala Vani which I staged in Mumbai (Mysore Association) and for the Singapore Indian Fine Arts Society ( Singapore). One of the special pieces was an abstraction of the concept of Saraswvati represented through sounds of the veena, and the sounds of the mridangam representing Bramhma who is described in various myths and songs as keeping rhythm or tala. This piece was called Veena –mridangaSamvaada.

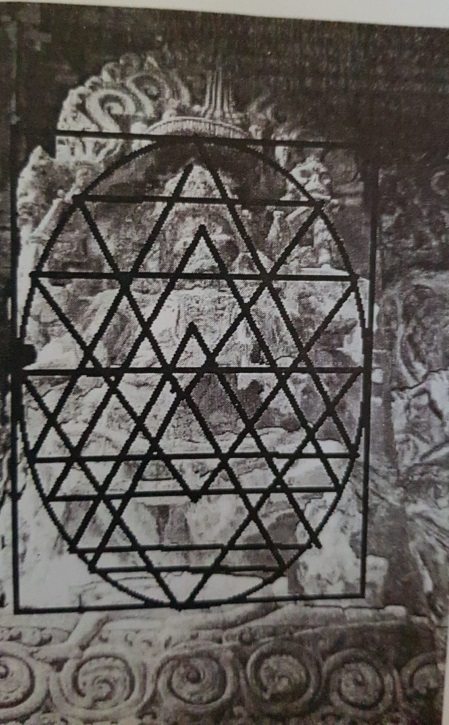

In conclusion, there are many more interesting features which come up on further study of these sculptures. I venture to speculate that if one study ies further the positions of these dancing Shaktis in the architecture of the temple, they may be in a pattern which forms the central chakras of the Sri Chakra cycle. Thus the divine feminine power of Shakti in its benign and ghorarupas are depicted in Belur and Halebidu. Discovering these subtle features, like the regular and recurring presence of the dancing Shaktis, makes one wonder about how many more interesting details remain to be unearthed in the glorious history and architecture of the Indian classical arts.

(Note: All Images are taken by the author on site at Belur and Halebidu and are part of the doctoral dissertation)

Selected Bibliography

Davis, Richard H. Ritual in an Oscillating Universe: Worshipping Siva in Medieval India. Princeton University Press, 1991. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt7zvz4s.

B Lewis Rice. Mysore : a gazetteer compiled for government

New Delhi : Asian Educational Services, 2001

Siri Rama . Doctoral thesis:Dance Sculptures of the Belur and Halebidu temples. (Submitted to the University of Hong Kong). Banerjea, Jitendra Nath. The development of Hindu iconography. Calcutta : University of Calcutta, 1956.

Brown, Robert L. (Editor). : studies of an Asian god. Albany, N.Y. : State University of New York Press,1991.

Chattopadhyaya, Siddheshwar. in the perspective of ancient Indian drama and dramaturgy . Calcutta : PunthiPustak, 1974.

Collyer, Kelleson. TheHoysala Artists : their identity and styles. Mysore: Directorate of Archaeology and Museums,1990.

Czuma, S.J. ElloraA doctoral thesis submitted to the University of Michigan,1968.

Deva, Chaitanya B. Musical Instruments in Sculpture in Karnataka. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass and Indian Institute of Advanced Study (Simla), 1989.

Govindarajan, Hema. Dance Sculptures in Karnataka. A doctoral thesis submitted to Mysore University,1990.

Gupte, Ramesh Shankar. Iconography of the Hindus, Buddhists, and Jains. Bombay : Taraporevala, 1980.(2nd ed.)

Kalidos, Raju. ’s Mohini Incarnation : an iconographical and sexological study. East and West, Vol 36, No.1-3,1986, pp.183 -204.

Kinsley, David.

__________________Hindu Goddesses: Visions of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Tradition. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers,1987.

__________________The divine player : a study of Krsnalila . Delhi : Motilal Banarsidass, 1979.

Mani, Vettam. Puranic Encyclopaedia. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, 1993 (Reprint)

Nandagopal, Choodamani. Dance and Music in the Temple Architecture. Delhi: Agam Prakashan,1990.

Natarajan,B. Tillai and Nataraja. Madras : Mudgala Trust, 1994.

Raghavan,V. Bhoja’sSringaraPrakasha. Madras : Raghavan, 1978.

Rao, Gopinatha. Elements of Hindu Iconography.(Vol 1-4) Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, 1993 (First published in 1914).

Rao, Ramachandra S.K.

_______________Art and Architecture of Indian Temples (Vol I) . Bangalore: Kalpatharu Research Academy,1993.

_______________Art and Architecture of Indian Temples (Vol III) . Bangalore: Kalpatharu Research Academy,1995.

Rele, Kanak. MohiniAttam, the lyrical dance. Bombay, India : Nalanda Dance Research Centre, 1992

Tarlekar,G.H and Tarlekar, Nalini. Musical instruments in Indian Sculpture. Pune: Pune Vidyarthi Griha Prakashan,1972.

Vatsyayan, Kapila. Classical Indian Dance in Literature and the Arts. Delhi: Sangeet Natak Akademi,1968.

EpigraphicaCarnatica Vol I,II,III and V (OS) (1886-1903)

Published by Motilal Banarasidass

Varaha Purana (1985)

Padma Purana (1988-1992)

Siva Purana (1970)

Kurma Purana (1981-82)

Bhagavata Purana ( 1976-78)

Agni Purana (1983)

Feature Image Credit: newindianexpress.com

Watch video presentation of the above paper here:

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.