The story of King Pandu and the curse that he earns at the hands of a hermit are quite well known. It is a turning point in Mahabharata – the penultimate one, the last turning point being his eventual death after which Mahabharata plunges into the conflict between the Kuru princes. What is not well known though is the immense detail of this episode, and the perspective hidden beneath the detail.

After the success of his military campaign, King Pandu retreats himself along with his wives into the Himalayan forest. He has been working very hard – first as a pupil, as a prince, then as a king, and finally as the leader of a campaign. Naturally, it is a well-earned retreat that is designed for him to recharge himself and live with a free mind. Pandu’s life has been one of a tight discipline, and now in the absence of a watchful ecosystem he lets himself loose.

The net result is he over-indulges in that great kingly pastime of hunting. Hunting, apart from being addictive, also builds a certain insensitivity towards life. It can be disastrous when it crosses a line. It involves being on the move continuously, with an immense focus on the target at great speed. Speed always blinds to realities other than the very purpose itself.

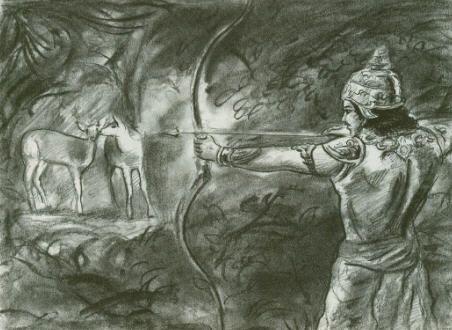

One day, King Pandu was as usual on the move for his hunt with his bow and arrow. Soon he encountered a herd of deer. In that was a pair– a male and a female, blissfully unaware of the world, in an embrace of deep love for ecstasy. The hunt, the speed of the hunt, the thrill of the hunt, the sense of power that comes with it, and continuously being in it, blinded Pandu. He did not think twice whether it was just to target animals in deep love.

He picked five beautiful arrows with golden wings, describes Mahabharata, signifying Pandu’s passion for hunting, completely oblivious of the tender moment of love on the other side. Rather, it may have been that very passionate moment on the other side, which increased the thrill of his hunt – Mahabharata is quiet about it.

The result though, took all the thrill away from Pandu. What fell was not a deer. One of them escaped and the other which fell was not a deer but a hermit, the son of a sage. What ensues is an unforgettable conversation between the King and the hermit, and a dwelling upon what is right and what is wrong. The hermit, pained by the shot of the arrow, hurt by the denial of ecstasy, and enveloped by the sorrow of his life ending begins with very harsh words.

“Oh King, how could you indulge in a wrong that even the lowest, the most unlearned and the ever indulgent in the wrong would hesitate to do. I know that one is not beyond one’s destiny, one’s burden of the past deeds. However learned and farsighted you are if fate decides an act it is difficult to better that. Yet, being born in a dynasty of ones that upheld dharma, how could you be so guided by desire and greed that you lost a sense of perspective?”

Nobody had ever dared to reprimand Pandu and question his dharma. Here a deer, speaking in the voice of a man, was doing the unthinkable. Pandu recovering from the shock responded that hunting was a pastime that was allowed for kings. It was an acceptable practice sanctioned by dharma for kings. Further he cites references from the past in his defense. He has still not understood where he crossed the line. The deer patiently responds but with a rhetoric.

“Oh Rajan, even when you hit the enemy, you are not supposed to do so when the enemy is already in a disadvantageous situation, or in trouble, or when not ready yet for the battle. Only in a direct battle can an enemy be killed. Nobody goes behind an enemy, and kill from the back. How could you then kill me?”

Amused Pandu says, “Oh deer, all that you said applies to an enemy. How does it apply to you – you are a deer! Even if I alerted you, you would run, and I would still have to hit you from behind”. Pandu has not realized his folly yet.

The deer now reveals, “Oh King, neither do I blame you for hunting animals, nor for hurting and paining me. But did you not see that we were both in the deepest of love, and in the most gentle and sensitive of our being. Could you, at least, not wait till we passed our ecstasy? When did kings become so cruel and insensitive to deny ecstatic moments that nature grants equally to all animals? Don’t you realize that this is the right of all animals? Your act certainly does not behoove your being a great king, born in that great dynasty that always upheld dharma- the kuru dynasty. You have learnt all the Vedas and associated Shastras. You should have known the importance of the moment. Your act is very cruel, one of adharma, one of immense wrong, something that could deny you of a place in the exalted worlds, which merit grants great men. A deplorable act, Oh King Pandu!”

By now, King Pandu had come to his senses. He was staring at his blunder with wide eyes, full mind, and complete self. There were no words that could either give him a chance of defense, neither could anything console the deer speaking in a man’s voice. The deer now introduced itself “Oh King, I am not a deer. I am Kindama, a hermit, son of a sage. Shy of being in love with my wife in the open, when surrounded by many, we both took the form of a deer for our love, and roamed around the forest freely in the open. Alas, you have pained me when I was in my most vulnerable sensitive joyous state. You have killed me when I was in an embrace of deep love. I curse you that you will meet the same end, the moment you touch your wife seeking the same moments”. So saying the hermit breathed his last, his life leaving the body forever.

The enormity of the tragedy had struck Pandu. With great difficulty Pandu came back from the deep forest back to his Royal tent. His lament to Kunti and Madri after his return is worthy of attention. King Pandu squarely blames his own excessive passion for hunting as the reason for his folly. However, the way he speculatively traces the root of his passion, what he ascribes it to is interesting.

Even though he was born from the divinity of Sage Vyasa, Pandu says, his namesake father Vichitravirya, and his overindulgences in pleasure, seem to have had an indirect influence on him. In summary, he places the blame more on character of a person in the ecosystem, than on birth of anybody even for an indirect influence. There is no blame on Vyasa, his mother, and even his grandmother who was not from Royal family.

In the Mahabharata, even for a poetic impact, reasons come from the character of a person from the past, and not anything else. This demonstrates the importance associated with personal character in the perspective of Mahabharata. Pandu then goes on a lengthy lament of how he proposes to spend the rest of his life in the path of renunciation.

A question that begs a reflection here is- did King Pandu not know that even an animal in such a vulnerable condition cannot be killed- being a man of such immense learning and training- when the civilization considered it as anathema? It is most likely that Pandu knew. The very fact that he freezes without an answer to the questioning of Kindama is a testimony to that. Yet, what happened to him in that moment? The episode seems to allude towards the blindness that one risks in excessive quenching of a passion, particularly one that requires hitting a target, and an excess of speed- like hunting. It blinds you even towards something as fundamental and as obvious a reality, as two living beings in their most beautiful moments, that very moment which sustains life, and that very thing becomes their vulnerability. Even the most learned can lose their perspective in that moment, and the quenching becomes more important than what sustains life.

King Pandu himself is born of divine grace of Sage Vyasa. Yet, divinity did not fulfill itself completely in his birth. His mother, Ambalika, went pale with an unpleasant white (pandu), aghast by the looks of Sage Vyasa, resulting in Pandu as well born pale- he went with that name. Amba on the other hand, closed her eyes, and her blindness resulted in Dhritarashtra born blind- physically and in his abilities of discretion.

The maid on the other hand received the grace of Vyasa in full- Vidura born to her is the only person with absolute clarity of perspective, and action in Mahabharata. At all times, Vidura demonstrates a clarity and conviction that others do not. When the elderly Bhishma is considering marriage alliances for Dhritarashtra and Pandu, the first person he consults for advice is Vidura; who is actually much younger, leave alone the elderly Bhishma or Kripacharya.

Vidura’s mother’s ability to receive divinity in full is unaffected by her Varna, community or the nature of work- Mahabharata upholds the individual abilities in these aspects. Dhritarashtra gets married to the best of the ladies of that time- Gandhari, a lady of great perspective. Yet his ability to receive her wisdom is limited, instead his blindness has a reverse influence on Gandhari.

She chooses to cover her own eyes- metaphorically signifying that Dhritarashtra’s lack of perspective is going to limit her wisdom coming to action in the future. Kunti is another lady of great knowledge and experience. She held the difficult task of the care of Royal guests in the kingdom of Kuntibhoja. Yet, her wisdom does not reach Pandu, and curb his indulgence in hunting.

The story moves on. Having learnt his lesson, Pandu then lives the life of a great hermit. He realizes beauty in renunciation. Through and through, it is Kunti who holds the threads of the family, and ensures that Pandu is all the time safe, far away from the reach of the curse. But then, our karma and the destiny strike to haunt us.

After the birth of Pandavas, in ways acceptable to the tradition, Pandu grows in confidence. In the month reserved for Manmatha, knowing fully well that he is ready to strike with his flower arrows of romance, Pandu enters a space where Manmatha is active. Madri’s repeated requests for self-control does not deter Pandu, and upon touching her, he is immediately affected by the fatal curse, and collapses to his death.

Thus, a mere Divine Grace is not enough, one has to receive in full with all of mind, body, and thought and hold it, if it has to fulfill itself. Pandu’s birth was one of unfulfilled divinity. This incompleteness manifested itself in that great folly of King Pandu- his passion got the better of his knowledge, to such an extent that he paid a huge price, and along with him the entire Kuru dynasty.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.