जीर्यन्ति जीर्यतः केशा दन्ता जीर्यन्ति जीर्यतः

चक्षुःश्रोत्रे च जीर्येते तृष्णैका तु न जीर्यते

“When the body ages, the hair also ages. When the body ages, the teeth age. The eyes and ears also age. However, thirst is not destroyed.” [Ch 7, Dana-dharma Parva]

Some of the characters in the Mahabharata lived long lives. Even Arjuna was about to become a grandfather when the great battle was fought in Kurukshetra. Bhishma also was also very old. Remember that Devavrata had been a young lad when he took the terrible vow that allowed his father to marry Satyavati. He was already a young man when Vichitravirya and Chitrangada were born to Satyavati. Her grandsons were Dhritarashtra, Pandu, and Vidura. So Bhishma was even older than Arjuna’s grandfather would have been!

Dronacharya loved his son, Aswhatthama, too much. That love drove many decisions Drona took in life. Ashwatthama, on the other hand, loved his own life too much. That much we know because Bhishma says as much on the eve of the war. “He loves his own life too much. This brahmana always wishes for a long life. [Ch 164, Udyoga Parva]”, and after the war, Ashwatthama confesses, “I was scared of saving my life. I released the weapon out of fear. I was scared of Bhimasena.[Ch 15, Aishika Parva]”

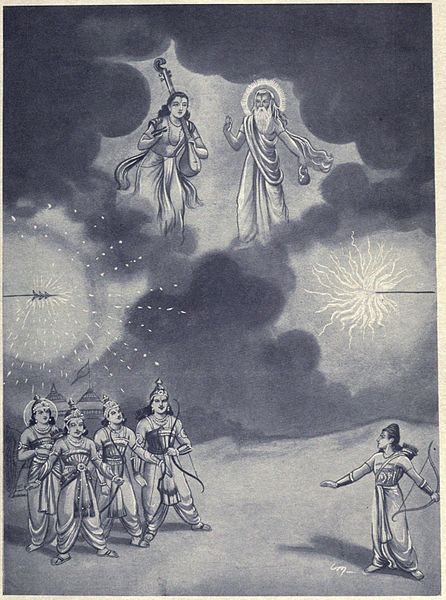

Coming back to Dronacharya, he got his wish – a cow for his son that would give him milk. That episode also turned an innocent childhood friendship into a lifelong enmity. That enmity did not end well for anyone. Dronacharya’s disciples – the Pandavas – defeated Drupada and Drona then humiliated Drupada, taunting that the two were finally equaled, taking half his kingdom away. From the fire of revenge that burned inside Drupada arose Yagnaseni and Dhrishtadyumna. Draupadi’s beauty in turn became the cause for much havoc that was wreaked by the Kouravas and Karna. Drupada was killed by Drona on the battlefield of Kurukshetra. Drona was later killed by Dhrishtadyumna. Dhrishtadyumna himself was killed by Ashwatthama after the war had ended. But that was not all. Ashwatthama then sought to kill the last of the Pandavas – the unborn son of Uttaraa and Abhimanyu. Remember that the five sons of Droupadi has already been killed by Ashwatthama.

Was Ashwatthama’s love for his own life an unrequited one? No. But that long life came with a curse. A long life can be a curse, but in this case, it was also a literal one. Uttered by none other than Krishna himself. To live alone for three thousand years. So fearful was the curse that it is instructional to repeat it here in full:

“You survive by killing those who are children. That is the reason you will reap the fruits of your wicked deeds. You will roam around the earth for three thousand years. You will never have a companion and will never be able to converse with anyone. You will be alone and have no aides. You will roam through diverse countries. O wicked one! You will never find a station amidst men. You will have the stench of pus and blood. You will dwell in desolate regions and in wildernesses. O evil one! You will roam around, ridden with every kind of disease.” [Ch 16, Aishiki Parva]

A similar example is one of Yayati. He did not love his own life as much as he loved the pleasures of youth. A conscious indiscretion with his wife’s servant and once friend -Sharmishtha- led him to being cursed by none other than his father-in-law, Shukracharya, to lose his youth. Yayati pined for the unsated pleasures of life that he thought would be his but were now to be denied. Here, again, we have several curses in play. Yes, one curse that was pronounced by Shukracharya, but there were four additional curses that were pronounced by Yayati! One curse begat not one more, but several more curses. A pining Yayati went to his sons, asking them to exchange his old age with their youth. All but one refused. All but one were cursed by Yayati. Hear how his sons refused their father’s desire.

Yadu: White hair and beard, cheerlessness, flabbiness, wrinkles on the body, ugliness, weakness, thinness, incapacity to work, defeat by the young and forsaking by those who depend on you – I do not wish for this old age.”

Yayati: Therefore, your offspring will have no share in the kingdom.

Turvasu: I do not desire old age. It destroys all desire, pleasure, strength, beauty, intelligence and even life.

Yayati: Therefore, your lineage will become extinct.

Druhyu: One who is old cannot enjoy elephants, chariots, horses or women. Speech fails him. Therefore, I do not desire this old age.

Yayati: Therefore, the most cherished of your desires will not come true. You and your lineage will not be kings, but will have the title of ‘Bhoja’.

Anu: Those who are old eat like children, drooling and unclean at all times of the day. They cannot pour offerings into the sacrificial fire at the right time. I do not wish for such an old age.

Yayati: Since you have described so many faults associated with old age, old age will overcome you. Your offspring will be destroyed as soon as they attain youth. You yourself will not be able to perform any sacrifices before the fire.

Puru: O king! I will take upon myself the guilt and the consequent old age. Accept my youth and enjoy pleasures as you wish.

Yayati: Since I am pleased, I will grant you this. Your offspring will rule the kingdom, be prosperous and accomplish all their desires.[Ch 79, Adi Parva]

So Yayati finally got his wish for a long and youthful life, at the end of which he realized that there is no end to the desires of youth. But Puru, the youngest of Yayati’s sons, did end up as the heir who ascended his throne after Yayati. Interestingly, Bhishma would, generations later, would take a vow of celibacy.

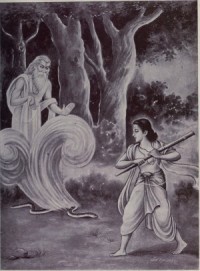

But a contrarian example of this love for a long life comes to us in the form of the Pramadvara’s story. She was the daughter of the apsara Menaka and Vishvavasu and brought up by sage Sthulakesha. Soon after she got engaged to Ruru (great-grandson of sage Chyavana), she was bitten by a snake and fell down dead. A grief-stricken Ruru lamented loudly in the forest. A messenger of the gods offered this bargain to Ruru – if he gave up half his life to Pramadvara, she would rise from the dead. Ruru agreed, and with Dharmaraja’s (Yama) approval, Pramadvara rose again. Ruru was delighted, but a burning angst against snakes lingered. I have told that tale in an earlier post, on how Ruru became the vehicle for the subsequent sarpa-satra yagya that becomes the stage for the first public retelling of the Mahabharata.

Finally, there is Dhritarashtra. The old king, having lost his kingdom and his sons had to live with his vanquishers, the Pandavas, after the war. Bhima was especially cruel, taking care to boast within earshot of the blind king how he had killed each and every one of his sons. When the blind king finally decided he has had enough, fifteen years had passed. He decided to retire to the forest, but was by then a very old and broken man. The man who once ruled over Hastinapura and whose strength had terrified even Bhimasena had been reduced to infirmity and penury. When he joined his hands in salutation, they trembled. He had to lean on Gandhari for support. The very act of talking tired him out. The king who had once the untold riches of the earth in his coffers now had to ask Yudhishthira for some wealth to perform a funeral ceremony for those killed in the Kurukshetra war – Dronacharya, Bhisnma, Somdatta, Bahlika, his sons, and others.

Dhritarashtra lived a long life, most of it as king, seeing his eldest son act out his unrequited desire of becoming king, even if it came at a great cost. His curse was to never be able to see his son’s faults. His curse was to see his sons die before he did. His curse was to live for many years after that. His curse was to die in a great forest fire from which he could not even run away. The fire of envy that had been his constant companion all his life engulfed him in a literal sense. A long life eventually came to a wretched end.

Long lives are not always happy lives. There is no ‘happily ever after’ in the Mahabharata, the greatest mirror to life that has ever been composed.

Disclaimer: views expressed are personal.

Note: the chapters and text quotes from Bibek Debroy’s English translation of the unabridged Mahabharata, published in ten volumes by Penguin India.

Figure 1 – Arjuna and Ashwatthama unleash their Brahmastras against each other, as Vyasa and Narada arrive to stop the collision. (image: Gita Press)

Figure 2 – Ruru hitting a dundhuba (image credit: http://www.anaadifoundation.org/blog/mahabharata/ruru/)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.