Diwali, the biggest, the brightest festival, is here. The best part of Diwali for many of us who grew up in Delhi, was not the day itself but the months that lead to its celebration. For some the celebration season began with Janamashtami for others it began with the Navratri. For our neighborhood it began in June, when all the uncles and aunties who were going to be on Ramleela stage came together for a ceremony called gana-bandhan. All those participating in the yagna would take an oath as the priest tied mauli (sacred red thread) around their wrists. From then till Dussehra, all the actors in Ramleela would sleep on the floor and abstain from meat and alcohol. The pledge prepared them for their respective divine roles (that includes those playing the asuras) and also worked as a detoxification period.

For us children June-September was filled with anticipation of the excitement we all felt for the ten days our Ramleela was staged. Our playtime during these months included a run to the school building in our neighborhood where Ramleela rehearsals were performed. The sing-song voices of the actors echoed in empty halls as we watched mesmerized and wondered how could they flawlessly hold such long monologues and dialogues. Being a part of ‘Our Ramleela’ was educational on many levels. Long before Ramanand Sagar’s televised epic we knew about Meghnath, Mareech and Manthra. In between the rehearsals were practical jokes and friendly jibes, home-made food and custom-made fun. So we also learnt about working together and making friends.use

So awe inspired were we by Ramleela, that one year we tried to emulate it by setting up a children-only version a few weeks before the one managed by the grownups. But after our Hanuman had a bad landing because the clothing line from which we made him swing broke, we realized we were not rightly equipped and quickly abandoned the idea.

‘Our Ramleela’, like others in Delhi, was a community affair. All ages were included, everyone was considered. The actors, organizers and prompters (those who whispered the lines, if and, when actors needed prompting) were mostly from our neighborhood and had known each other for years if not generations. Most of the actors carried their stage identity for life, “You know the boy who played Shatrughna three years ago? He is getting married next month!’ Many roles were performed by several consecutive generations of the same family. Those with melodious voices were responsible for playback singing. And like all Ramleelas ours added its own flavor. Destruction of Ashok Vatika was a favorite with children, because Hanuman uncle made sure that he threw some of the fruits into the audience. Children jumped up to catch the fruits. Our parents ensured that we shared our loot, because it was actually – prasad.

One year our Ramleela upped its game and broadcast the performance on a local channel for the elderly who could not make it to the grounds. To be on Ramleela stage was the ultimate destination for most children. To get a speaking role was like getting crowned. Ordinary ones like us worked hard and showed our dedication by showing up regularly. Most of us took pride in being gophers. Lucky ones were offered a small stage appearance without any lines. With age, some of us graduated from roles like a vanar in Hanumanji’s sena or Seetaji’s saheli (friend) who had no lines to deliver to Kumbhkaran’s or Tadka’s assistant, that were names to reckon with and even had a few words to their stage credit. It’s a different story that no one recognized us off-stage, if we played those roles, so we had to promote ourselves. ‘I, the Tadka’s assistant’ in the last night’s Lanka Dahan episode, had so much fun chatting with Hanuman Uncle in the wings!’ We would brag in-front of those who were either new to the neighborhood or had never participated in Ramleela’s activities.

Then there were Dhan Uncle and Chabbra Uncle who were the main organizers. Dhan Uncle even managed to play some poignant roles alongside overseeing the production. Although most of the actors were well known to our parents, for us they were no less than movie stars. It was a matter of pride to know them personally. So we showed-off our celebrity connections. Actually, some of the vanars themselves went to become celebrities. e.g. King Khan. Yes, Shahrukh Khan got his start on our Ramleela stage.

For years our Lakshman and Seeta were hired from professional theatre companies. While our Seeta would change every year for scheduling reasons, the gentleman who played Lakshman stayed with us for many years. So, he was addressed as Lakshman uncle! He was of medium-height with deep skin color like Adishesha. Over the years he became a part of our community, and would ask about our school and often comment on how big we had grown since he saw us the year before.

Pandaal(temporary arena) preparation began a couple of weeks before Ramleela. We arrived every evening at the park to oversee our miniature city of lights being created by artisans.

A distinctive aspect of our Ramleela was that two days were dedicated to ‘social or historical dramas’. The plays were either dealt with contemporary issues or historical and focused on more recent itihaas. During those days the stage would turn either into a middle-class home and Ram and Lakshman turn into Rajat and Lalit, or a battle field and our Parshuram slip into the role of Porus.

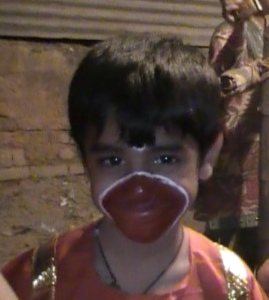

Because speaking roles required time away from school activities, parents often restricted their children to being an extra on the stage. So, professional child-actors were hired for roles that required time-commitment. When I was in seventh grade, my father suggested that instead of hiring child-actors, children of the neighborhood be allowed to take speaking roles as well. It not only saved the committee some money, but also gave children an opportunity to get over their stage fear. My first role that year on stage, though still without any lines was a significant ‘individual’ role, rather than being part of a crowd. I played the beautiful golden stag that mesmerizes Seeta. The make-up artist gave me a yellow robe in silk with gold embroidery all over it. He made my eyes in Kohl and glitter, and handed me faux deerskin mittens before I hopped onto the stage. I remember rehearsing my hop and neck movements for an entire week! And after the scene I ran into the audience with my makeup on—so everyone would know that the ‘deer’ was ‘I’. From then on, I acted in plays, was given an odd line to deliver and became a part of the much-coveted acting team. My favorite moments were acting alongside most admired characters in Ramleela—Uncles Ram, Lakshman and Angad. The most memorable and satisfying role came to me when I was in tenth grade. I was asked to play Shabari. My fourteen-year old self was to be transformed through make-up into an octogenarian. My father and Yash uncle were my acting coaches, training me to behave like an old woman immersed in shraddha awaiting Lord Ram. Yash uncle, who was actor, director and make-up artist all in one, handed me a wig with disheveled hair, darkened my front teeth, and asked me to say the lines again, before I went to the stage.

On the stage my real-life love for the epic came over me and for a brief moment I became Shabari. Soon as Ram Uncle entered the stage my eyes became moist, I stared at him and forgot my lines. His presence was divine. He embodied the role in his gentle yet royal gait and a polite tone and I did the same in my body-bent from age, tired of the years but immersed in emotion at the sight of my life-goal. I kept the bowl of berries that I was holding on the floor and continued to stare at him. Ram Uncle, realizing something was amiss, said, ‘Ma, kuch khaane ko milega?’ (Mother, can we get something to eat?)

That line did not exist. Ram Uncle made it up to bring me to the present. I did and we continued with the entire scene. Years later I learnt that Ma Shabari – was a Bhil woman -today identified as scheduled and as a backward caste. What a lesson I learnt in playing that role! I was the Bhil woman herself and the love that I felt connected me to any other devotee regardless of divisions such as caste and color. More importantly, Bhagwan Ram willingly ate from my hand, the berries that I had tasted before.

The experience of feeling inside the grand epic was not mine alone. We were told that when Ram Uncle returned to his house on the last day of Ramleela his parents performed aarti, as they would in a temple. And even outside of the Ramleela days, we lived as if we were all part of the Ramayana. We never learnt their real names. They were always, Uncle Ram, Uncle Ravan and Uncle Hanuman to us. Performance of Ramleela, is a collective enactment of a story that allows the community to experience– deception, love, pain, sorrow, joy and transcendence. A creative and wise way of bringing vyavharika (the worldly) and paramarthika (other-worldly) together.

One amusing incident has always been a reminder of that. Once, when I saw a young child play with Hanumanji’s ankle-bangle before he stepped on the stage, I tapped his head and told him to lay it off, ‘What’s it to you? I’ll do what I want’ he snapped at me, ‘He is my Papa!’ There it was! Our celibate God played by a householder, who lived by the rules of bramahcharya for a few months every year in preparation for his stage-role, but never gave up on being a provider for his family –in the real world. A father off-stage, was a Ram-bhakt on-stage -who could fly at the speed of wind. And the entire audience did not find any conflict in both pieces of information.

Staging of the Ramleela is an equivalent of living through of the epic, and a reminder that life itself is a sacred lila. It was so obvious in the way every actor bowed to the stage, before they stepped on it. As if bowing to the trials and tribulations of this sansar in gratitude for being our teachers. In a sense each one of us, no matter the gender, age or role that we played on-stage, was a soldier in Hanumanji’s army. In our own humble ways we contributed by acting or by being an audience.

For all the days Ramleela was staged, bhajans would start blaring from early evening and stop around 10 pm, when Ramleela started. All evening we conducted our household activities to the background sound of bhajans. For the viewing most of us carried our blankets and shawls and requested those arriving before us to save us seats in very own open theater. The precise expression was, ‘jagah mal lena hamare liye’ (secure a place for us). Street vendors were allowed inside during the scene change and we made sure our parents brought their wallets. Many working people chose to watch from their balconies. But we children were allowed to stay up and wake up late, for we had ten days school-break for Dussehra. In the last few years, with changes in school schedules which do not allow for ten-days of break during Dussehra (but add a few extra days towards the end of the year coinciding with Christmas), Ramleela has suffered. The audience is increasingly a migrant population who are transient residents of the community.

Ramleela cannot be understood outside of this unique phenomenon where actors and audience rotate to create the ultimate experience. Uncle Ram from my time, who was also our primary playback singer, has graciously retired into playing Khewat, the tribal man who helped Lord Ram cross the Saryu river. The deliverer himself became a devotee! Vikas, Dhan Uncle’s son now plays the role of Dashrath like his father did for years. Most Ramleelas even today are a community affair. Every community that wishes to enjoy the by-products of staging Ramleela i.e. community building and maintenance will need to make some conscious adjustments in our media abundant age. Possibly our time in front of TV and digital media will have to be reduced. Instead, we should use technology in service to the project e.g. researching and connecting. We will need to focus on being creators rather than consumers if we want to continue to create collective memories!

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.