I grew up in Bangalore, not too far from the iconic home of Sudha and Narayana Murthy. It was all joint families full of strivers around me, all a few missed salary slips away from the streets. Families headed by a stressed-out father, a put-upon mother, an imperious mother-in-law whose imperiousness was borne more out of fear of slipping back into poverty than self-gain, and tons of uncles, aunts, and short, skinny, limp-wristed children who were expected to study hard and get a stable job.

The most representative of these children was my neighbour Madhu. He was a few years older, wore glasses too thick and large for his face, got the best marks in his class full of strivers, was highly regarded for his recitation of shlokas at the RayaraMatha nearby, and hoped to get a job at a PSU and take his mother and sister away from the poverty-induced stresses that worsened his father’s stress and his grandmother’s imperiousness.

Madhu got the best possible CET rank, went to BMS College, and was recruited into Infosys. Within a year, he was taking resumes from everyone else in the neighbourhood of working age. His family spoke glowingly of the familial atmosphere at Infosys, which was all merit-based, and about how they once saw Narayana Murthy at their RayaraMatha on Thursday. Another year later, he bought a house in (what seems like) JP Nagar 455th phase, married a girl from a similar family he had met at Infosys, and soon, they both went away to the US to work ‘onsite’, returning sparingly to organize the weddings of his sisters.

Soon, Madhu’s achievements were dwarfed in the neighbourhood by Avi who got into IIT, Mahesh who narrowly missed the IIT cutoff but ended up in NITK Surathkal, and several others who were now prouder to work at ‘product companies’ like HP and Citrix rather than service firms like Infosys and Wipro. But it was clear that Madhu was the pioneer, the prototype showed us all that it was possible.

And in providing opportunities that harnessed the strengths of the Madhus of the world, Narayana Murthy was our hero. We weren’t blind to his other half, though. We all knew none of this would have been possible without the Sita-like Sudha by his side, she who had given her husband all her savings to start his company, and even mortgaged her gold bangles to tide over a rough patch. Not only that, she was smarter, grittier, and no less an engineer than he was.

Maybe it was Madhu’s mother who exemplified this best when she said of her son, “He only wants to marry someone who is as accomplished as him, like how Narayana Murthy married Sudha.”

The Murthy family were role models for us in more ways than one.

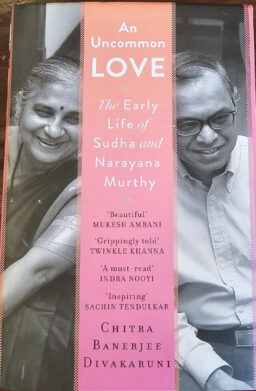

An Uncommon Love

The book opens with Sudha and Murthy meeting through a friend, bonding over books, and agreeing to meet again despite themselves. A meet-cute the bookish and nerdy dream of. And it only gets better from there.

There are tons of cute, touching anecdotes. Author Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni uses the entire storytelling playbook to paint an intriguing, sympathetic, relatable picture of the duo.

Sudha was seen as snooty as the only woman working on the TELCO floor who kept her distance for propriety, but once her colleagues saw her guide a lost blind woman, their opinion of her changed. Similarly, the principled Murthy sees an old woman struggling on a cold unreserved bench on a train and gives her his ticket and he sits on the bench all night instead.

They spend evenings out quite late together, and Sudha’s friends have to distract the security guards so she can sneak back into the women’s hostel after curfew.

Sudha loves movies and won a bet with her hostelmates that she would watch a different movie every day for a whole year. Murthy on the other hand, went to a midnight showing of Psycho at a tent in Siddagatta once, and ran back home, shivering in fear.

A contrast is painted between their upbringings too. She is surrounded by an attentive family, raised on her father’s doctor salary, which has her financially more stable than Murthy’s precarious situation. Murthy on the other hand has a father whose school inspector father’s meagre salary was the only income to raise eight children. Worse, his father is beaten down by life and isn’t outwardly affectionate with his family, which leads to an emotional distance between son and father.

Sudha is encouraged to pursue every opportunity that comes her way, with her family actively supporting her joining an engineering college when she’d be the only woman there, and helping her decide between going to MIT for a PhD versus being the only woman at TELCO. In contrast, Murthy has to forgo studying at an IIT despite getting a full scholarship, because the scholarship was only awarded at the end of the year, which would have made the financial situation of his family untenable.

Murthy on the one hand is a fervent communist who wanted to join the Communist Party of India, while Sudha, working with unions on a shop floor has different opinions. Murthy however tempers down his opinions after backpacking through Europe, when someone overhears a couple on a train in Eastern Europe complaining about the system to him, and he is thrown into a prison in Bulgaria with no food or water for three days.

Then there’s that time in New York City when Sudha is mistaken for a drug dealer and chased down by undercover policemen.

Winning stories. I’m surprised they aren’t going viral on the news and social media.

The real meat of the book is when they start their entrepreneurship journey. This is the uncommon love. They bet everything on Infosys. Their money, time, and family. Sudha put all Rs. 10,000 of her savings into Infosys. They sent their toddler daughter away to stay with Sudha’s parents, and only saw her on weekends. They used all their time to work on building Infosys. Those struggles spoke to me at a completely different level than anything else in the book.

A Culture of Struggle

I come from a similar background as NR Narayanaa Murthy. I am quite familiar with the RayaraMatha where the couple had their wedding lunch, for instance. I do have a family friend who cleared IIT-JEE back in the 70s, but couldn’t go because his family couldn’t afford it, and then went for an M.Tech instead, once he had earned enough to afford the wedding of a sister or two.

But what struck me the most as familiar was this culture where men felt wronged by life, used that to fuel their determination to achieve success, and expected nothing but full obedience from their children in that pursuit. Most familiar of all was a wife who was from a slightly more well-off background, full of confidence from a loving, nurturing family, and she often found herself holding the fort at home, making do with whatever they had, providing social lubrication for the family, never making demands of her husband because she knew there was already too much asked of him, and keeping her struggles to herself, like Sita. My grandmother was in such a mould, somehow feeding a family of ten on one salary, apart from anyone my RSS worker grandfather brought home for dinner with only a moment’s notice, and what’s more, she was named Janaki.

Sudha could easily have been the one holding the fort at home that way, and for a period, she was. On the birth of her second child, she stayed home with the children while her husband was away at work all the time. It could have quite easily gone the way every woman’s life in that era went. She herself figures it out and justifies it. Sure, she could be the hotshot running Infosys, but a piece of advice from her grandmother comes back to her – A woman can easily do a man’s job, but a man cannot do a woman’s job. She opts to be home with her children and get to know them, especially motivated by her very active and highly-strung second child. For a moment, you wonder how this is going to pan out.

And that’s where the character and experiences of Sudha Murty make a difference. She is a high-agency person who has always earned her own money. She writes bestselling books while her children play with their grandparents. When she can, she opts to be a teacher and wins awards for that. And eventually, she creates the Infosys Foundation and administers charity work. Most of all, she becomes the human face of Infosys and a public personality in her own right. This is what distinguishes her from other women of her background.

This is the best part about the book – it paints a picture of mutual love, support, and faith between equals whose relationship evolves from being equal in every aspect to giving way to each other to work on difficult dreams.

And Yet…

The book had me wondering about a few gaps in the narrative. We knew Murthy’s family had a house in Jayanagar. Why then did Sudha need her family to move from Hubli to Bangalore to help her raise the children? We don’t hear too much about Murthy’s side of the family, which does strike me as odd.

Another issue with the book is it seems to take most of its material from the columns written by Sudha Murty in the 2000s. There is not much new in terms of our understanding of them as a couple or what makes them tick. It could just be that they have been as transparent about their lives as they can be from the beginning, and nothing much has changed. Some new insights would have been desirable, especially seeing the author went to college with Sudha Murty’s brother.

The book also doesn’t take its time to put into perspective how completely exceptional both Sudha and Narayana Murthy were compared to everyone else in their generation. The issue here isn’t just education or risk-taking. It was about poverty.

The book goes into several episodes of the couple having to convince their families, their first few employees, and the families of those employees about the chances for success of Infosys. But to be in the league where you consider taking those risks, you had to have some kind of safety net. None but a small handful were able to both have the knowledge and ability as well as the safety net to do so.

In its initial years, Murthy’s penny-pinching tendencies when combined with the iffy cash flow of Infosys meant they didn’t pay as much as jobs that those proficient with a computer could get. All but a few were living paycheck to paycheck, and most people could not take a more meagre paycheck. Additionally, private software firms didn’t have a great reputation – Patni was notorious for missed paychecks – sometimes they wouldn’t pay their employees for 2-4 months at a time.

In the present era, we can point to how IITians get access to opportunities most of us don’t even know of, but back then, you had to be someone exceptionally blessed to even have a job that lets you build enough savings to afford risks.

But the part of the book where it falls the most short, is in how it ends and where it leaves us. It doesn’t bring their love story to a full circle. It started with two people so in love with learning and books, and who couldn’t stop talking to each other so much that they unintentionally went 11 hours on a train. By the end of the book, he is so busy building Infosys that he has no time for books or conversation. How do they reconcile being here from where they started? In what do they find the person they fell in love with? Is the happy ending supposed to be just the money and the children? The romantic in me who was hooked from the bookish meet-cute ended the book quite disappointed.

I do want to know where such a meeting of minds goes, emotionally. In that, this book comes short, stopping instead in the humdrum of their busy, separate lives.

What this Book Means for the World?

This book is a treasure trove of magic moments and interesting little snippets of recent history. JRD Tata chancing upon Sudha and giving her advice as they are starting Infosys. Azim Premji interviewing and rejecting Murthy. Long sequences of how difficult it was to navigate government offices and get permissions to do the most basic things. A government in power that believed computers qualified as ‘labor-saving devices’ that took jobs away from people, and hence deserving of curbs and disincentives. Murthy crying at the assassination of Rajiv Gandhi.

It feels like ripe material for a more down-to-earth Kannadiga version of Guru, the Abhishek-Aishwarya starrer, and I would say this tale needs to be told in every possible medium.

The current generation, who came of age in Amrit Kaal, have no idea how nearly impossible entrepreneurship was in India and have no clue of how brilliant, resourceful, and one-in-a-million you had to be to get anything done at all.

Those in their prime today only know NRN and Sudha Murty from their sparse media appearances and anecdotes stressing their simplicity or as the in-laws of the UK PM. They only know of Infosys as a consulting firm that pays low entry-level wages, and NRN’s exhortations that people work 70 hours a week. There is also a lot more that happened with Infosys and the Murthys in the past 15 years that cast a shadow on everything that came prior.

Instead, people need to be aware of the Murthys in their heyday, taking a victory lap with near-constant appearances in the Bangalore edition of the Times of India, being icons of inspiration to every middle-class family, and just ushering in a whole era of optimism and hope. On that, this book does a great job showing us what that looked like and how it got there.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.