Few Other Reformers

In this article, we will learn about the lives and teachings of a few other Jain reformers in brief, offering insightful glimpses into their legacies.

The modern era is marked by globalization, consumerism, and fierce competition. Numerous Jainas have migrated outside India in the pursuit of education, business opportunities and other endeavors. Presently, these Jainas, particularly those residing in America, Europe, Africa and Australia, are seeking to address the spiritual lacuna in their lives. They possess a thirst for religious knowledge that goes beyond the constraints of space and time, surpassing the traditional boundaries of Sramanacara and Sravakacara. In India too, there is a whole new generation seeking a religion that emphasizes on inner growth rather than focusing solely on food restrictions and other external rituals. They prioritize moral and ethical conduct over superficial observances. In today’s demanding world, we yearn for peace, love and compassion, rather than mere adherence to ahimsa and aparigraha. Even though one cannot escape the fast rising globalization, consumerism and competition, modern day reformers prioritize the internal, philosophical dimension of religion.

Pt. Banarsidasa, a lay follower hailing from Agra, lived in the sixteenth century and voiced his opposition against the institution of Bhattarakas. Acarya Vijayavallabha Suri, a Swetambara monk of the nineteenth century, aspired to pursue contemporary formal education, and additionally harbored intentions to contruct new temples while also undertaking the restoration of older ones.

To cater to the specific needs of the present age situtations, some modern spiritual leaders like Late Acarya Tulsi and Acarya Mahapragna, have carried on the reformation within the Terapantha sect. Leaders like Late Upadhyaya Amar muni and his disciple Acarya Candanaji have established the institution of Veerayatan to focus on social service. Late Sushil muni and Gurudeva Citrabhanu, initially a muni who later became a lay follower attempted to spread Jainism abroad. The latter three reformers are catering to the needs of young Jainas in India and as well as abroad.

Pandit Banarsidasa (1586-1700 A.D.)

Pandit Banarsidasa, born in 1586 A.D. in Agra, to Kharagasena of Srimalijati belonged to the Swetambara sect. Banarsidasa was a religious person. He learnt Pratikramana sutras, Samayika and other rituals. At the age of 14, he composed Navarasayukta poetry of 1000 verses. In 1623 A. D., he formed his own sect. Despite having two wives and nine children, they tragically passed away one after another. He himself died in 1700 A.D.

In 1623 A.D., Banarsidasa once visited the house of his in-laws. There he met a person who spoke of adhyatma fervently. This individual gave Banarsidasa ‘Samayasarakalasa’ to read. Banarsidasa, engrossed deeply into the text, began contemplating on its teachings. Slowly be began to realize the futility of the external kriyas and he also acknowledged that the real knot has not yet opened. He renounced the practices of japa, tapa, samayika and pratikramana, which had an adverse effect on him. He began eating food offered to gods. His three friends joined him in this. They would hurl shoes at one another, tossed each other’s pagadi around, enjoyed and talked about adhyatmamata. They disrobed and declared themselves as aparigrahi munis. Later on, Banarsidasa criticized the image worship. Until 1635 A.D., he remained in this form when one day a scholar named Pande Roopcanda of the Digambara sect arrived in Agra. Banarsidasa with his friends went to have a dialogue with him. Roopcanda explained to them knowledge and conduct in relation to gunasthanas. He even expounded how the inner niscaya and external vyavahara should both go together. When Banarsidasa heard this, he overcame his dilemmas and confusions. He was then a completely reformed person. He and his friends always called themselves adhyatmi.

In Agra, the Bhattaraka institution was famous. The initial aim of this institution was to preserve the Jaina culture from the invaders, to save the Jaina manuscripts and impart religious discourses. However, later on they forgot their original path and resorted to other practices. The supporters of the Bhattarakas are the bisapanthis. The Bhattarakas are semi-Jaina ascetics who managed large estates donated to temples and enjoyed supreme authority in religious matters. They installed images, conducted various ceremonies, possessed miraculous powers and enjoyed all aristocracy.

Banarsidasa, who became a devout Digambara sravaka observed the misconduct of these Bhattarakas. He declared that the Bhattarakas had strayed from their true religious path and had become parigrahi with reasoning that the true religious path is impossible to follow. They confined religion to mere external rituals claiming that this is the path to follow and never spoke of spirituality.

Banarsidasa exposed the real nature of the Bhattarakas and explained the true nature of religion on the basis of Samayasara. He wrote Nataka Samayasara and Banarsivilas to popularize his views. He denounced all forms of rituals. From the bisapanthis, he got followers who became terapanthis. They left 13 things which included ritualistic practices which were mistaken by the Bhattarakas to be the religious activities. The importance of Pandit Banarsidasa’s work lies in the fact that he courageously protested against the Bhattarakas who constituted supreme religious authority in Digambara Jaina tradition and criticized their way of following the religion.

Acarya Vijayavallabha Suri (1870–1954 A.D.)

(Figure 1: Credit: Wikipedia – Acarya Vijayavallabha Suri)

Chaggan was born in 1870 A.D. in Vadodara. At the age of 15, he had the opportunity to listen to the discourse of Atmaramji. Two years later, at the age of 17, he was initiated by him. He passed away in 1954 A.D, after successfully dedicating his life to the mission of spreading education.

Vijayavallabha was a disciple of the famous muni, Atmaramji Maharaja or Vijayanandsuri. In the days when there was a crusade against murtipuja, Atmaramji realized the merit of murti-puja and Vijayavallabha under his guidance erected nearly twenty five temples all over India and renovated many Jaina as well as non-Jaina temples.

A complete transformation of society through education was the main objective of his mission. He wanted an educational revolution in every corner of the country. He wished that the eternal flame of education and learning should illuminate every corner of the society. It is due to our apathy and laziness, and that instead of merely paying our tributes verbally, we should demonstrate it through deeds.

According to him, there were three important aspects of education – namely, the educational institution, the teacher and the student. None of the three should be ignored. He also gave elaborate thought to the economic needs of the teacher and emphasized that if the teacher were to work with devotion and selflessness his economic needs must be looked after adequately. It was due to his efforts, initiative and inspiration that the Jain community established several temples of learning (educational institutions) in various parts of the country such as Shri Atmanand Jain College, Ambala; Shri Parshwanath Ummed Jain College, Falna; Shri Parshwanath Jain Vidayalaya, Varkana; and various high schools, middle schools and primary schools at Ludhiana, Malrekotla and Ambala in Punjab. Many other educational institutions and girls’ schools in other provinces are shining examples of his devotion and dedication to the cause of education. In these schools and colleges, admissions were open to all students irrespective of their caste or religion. He says, “People today seem to be afraid of modern education on the assumption that it will destroy culture. I consider it a fallacy. If electricity burns sometimes it does not mean that it should not be used at all. Had this been the attitude of scientists, science and technology would not have developed. It will be not in our benefit to ignore the education prevalent in this age”.[1] Acarya Shri supported modern education too. He saw that many people were too narrow-minded and considered modern education as an unredeemable evil. He realized that the attitude of apathy towards contemporary education on the part of society would bring its downfall and make it orthodox and outdated.

In 1981 VS, during his monsoon-stay at Lahore, Muni Vallabha reluctantly accepted the title of “Acarya” after repeated requests from the Punjab Sri Sangha. He consistently declined titles and decorations with great politeness. Later on in 1990 V.S., he was given the titles of “Kalikal Kalpataru” (The tree of Heaven), and “Agnan Timir Tarani” (The expeller of ignorance and darkness like the sun) during the Porwal conference at the holy shrine of Bamanwarji in Rajasthan. Additionally, people honoured him with titles like “Punjab Kesari” (The lion of Punjab) and “Bharat Diwakar” (The sun of India). However, Acarya Vallabha was not interested in these titles. He accepted them only as expressions of people’s love and affection for him. His divine mission remained focused on the welfare of man and society. The Acarya himself used to say: “I do not want titles and decorations. I want good deeds from you. I want your achievements”.[2]

He said: “The Hindu, the Christian, the Muslim, the Parsi and the Jain all should win over their jealousies and try to live virtuous lives. Only love can make life great and noble”.[3]

While upholding ahimsa, love and mercy, these institutions should maintain a high standard of practical education too.

The importance of Vijayavallabha Suri’s work lies in the fact that despite being a monk trained in traditional religious teachings, he felt the need to obtain modern secular education. Furthermore, he translated his teachings into tangible actions by establishing various educational institutions operating under the same guiding philosophy.

Upadhyaya Amar Muni (1903- 1992 A.D.)

Upadhyaya Amar Muni, was a profound thinker, an eminent scholar and a saint of the highest order. He was born in 1903 A.D. in Godha, a small village Narnaul, a hilly town in present day Haryana. His father’s name was Lal Singh and mother’s name was Chameli Devi. He was initiated in the monastic order at the tender age of eleven. He possessed keen intellect, so he mastered himself not only in Jaina scriptures but also in Vedic and Buddhist ones. His conviction was that detachment, selfless service and knowing oneself are the essence of all the religions.

He was known all over India for his progressive interpretation of Jain scriptures in consonance with the present day scientific creative revolution. He fervently addressed the social, religious and political ills afflicting the people and offered practical solutions to remedy them.

He had, to his credit, a great number of publications spanning various literary genres and addressed a wide spectrum of human behavioural issues, both at individual as well as social level. He laid great emphasis on harmonizing the relationship between man and society. He devoted his life equally for the cause of religion and humanity.

He was a devoted votary of Anekantavada. So his line of thinking was truth oriented, free from prejudices and based on rightful thinking. He held that virtue and vice do not lie in action but in intention.

“Munishree was a true patriot. When Mahatma Gandhi was at Noakhali trying his level best to extinguish the blazing fire of communal hatred between the Hindus and the Muslims and to establish harmony and goodwill between them, he went there and met Mahatmaji and as a true follower of non-violence offered his services there. Not only this, he also took an active interest in political matters. Whenever he saw that there was tension among the leaders of different political parties, he personally went to them and by his political insight and logical arguments he very often succeeded in removing the differences and brought about a compromise. It was in appreciation of his patriotism that Smt. Indira

Gandhi, the then Prime Minister of India, decorated him with the title of Rastrasant”.[4]

“Munishree, a true karmayogi, firmly believed in the truth of the adage, ‘It behoves the great to be always active.’ On the pretext of being an ascetic who had renounced the world and severed all his connections with it, he never kept himself aloof from the world and its problems. He participated heart and soul in all the affairs and tried to lead the people on the righteous path”.[5]

In 1962, during his chaturmas in Rajgir, while meditating in the Saptaparni cave of Vaibharagiri, he conceived the idea of ‘Veerayatan’, a centre for social service. This remarkable site, steeped in historical and spiritual significance, inspired him to establish such an institution. In 1972, at the time of the 2500th Nirvana centenary of Lord Mahavira, he placed before an audience of monks, scholars and intellectuals the concept of Veerayatan. In 1973, his dream took a tangible shape. Despite strong and sustained opposition from people, Munishree succeeded in laying the foundation of Veerayatan. However, opposition was based on the grounds that Jainism in its most conventional form does not give permission to the monks to do any kind of social service. Despite all odds, under his affectionate patronage, it soon arose as a prominent Jaina socio-spiritual institution with now its branches in countries like the U.K, U.S.A. Canada and Africa.

Munishree had great respect for others’ sentiments. Whenever a devotee came to him and offered a gift, he, though himself totally free from desire, accepted it, thinking that his refusal might hurt other’s feelings. However, as soon as the donor left the place, he would hand it over to the person who was in need of it. Thus it can be see that one can follow the vow of non-possession

without hurting anyone’s feelings. Here it can be seen that it is always the intention and not any external act that binds you. Thus the notion of either indulging in cravings or vehemently renouncing everything worthy of rejection is evident from the actions of Muniji.

He thought deeply of the different deformities of the society and offered a practical solution to those problems. Accordingly, he called for a creative revolution in the society of women and attacked intensely the difference between men and women. In ancient India, women were given the status of a goddess. It was the ancient Indian culture about which he says, “The country in which a woman was once worshipped like a goddess now looks down upon her. It is not religion. It is non religion”.[6]

He was a great champion of the cause of women. He emphasized the significance of women as described in the ancient Vedas, Upanishads, Jain Literature and Tripitakas. “He has sung the glory of women in the times of Ramayana and the Mahabharata. He presents the sublime form of Sita, Draupadi, Kunti etc. in the strongest possible words. Describing the divine qualities of a few women of the time of Mahavira, he says, “The venerable women of the age of Mahavira bhagawan such as Arya Chandana, Mrigawati Jayanti etc. are shining stars of our history. The life of Arya Chandana is the pious Triveni of Karma, Knowledge and power which will keep on flowing as a source of inspiration for all human beings for all the time to come. The story of suffering of Chandanbala is a burning example of the devilish nature and social disorder of the then male-dominated society. Mahavira, who brought her out of her suffering life was an inextinguishable light of ‘Karma Yoga’ and made her the chief spokeswoman of a huge ‘Samgha” of 36,000 sadhavis whom she led very successfully”. [7]

Maharaj Amarmuni has mentioned the luminous ladies of the Buddhist Tripitakas and Jataka stories whose lives are ideals for the whole of women-folk. This great saint Upadhyaya Shree Amarmuni left for his heavenly abode on June 1, 1992 His legacy is carried forward by Acaryacandanaji.

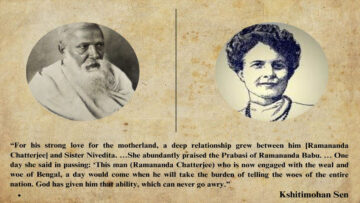

Acarya Candanaji (1937 –till date)

(Figure 2: Credit: Wikipedia – Acarya Candanaji)

Acarya Candanaji is one of the most controversial ascetics of the modern reform movement in Jainism. She was born in 1937. Her parents Manek and Prem, named her Shakuntala. She was ordained at a very young age of 14 by Acarya Anandrishi. She was impressed by the fact that Mahavira did not confine himself to personal spiritual perfection, but dedicated his life to the cause of social reconstruction through ahimsa, aparigraha and anekantavada. “Convinced that Mahavira’s central message of ahimsa is in reality a call for the service to humanity and all living beings, in 1972 she decided to join a group of nuns under the guidance of a reformer, Sri Amar Muniji. True to the spirit of Anekantavada, she studied Jain as well as non-Jain scriptures with great ease. In 1986, at the age of 49, her spiritual progress was recognized in the form of a promotion to the monastic rank of “darshan acharya”.[8] On 26th January 1987,. Amar muni bestowed upon her the title of Acarya.

Another aspect that left a profound impression on her was Mahavira’s message of equality. Mahavira’s four-fold samgha was a society of equals, devoid of barriers of caste or gender. Mahavira readily welcomed individuals, regardless of their caste or gender, into the samgha, guiding them through their ascetic hierarchy, based solely on scholarly merit and spiritual advancement. He appointed both men as well as

women, to head the ascetic orders, and notably, the head of all nuns during his time was a nun called Acarya Candanbala. Unfortunately, as it also happened in other faiths, with the male dominance in the society, the hierarchical positions of Jaina nuns later became secondary to those of the monks. The new monastic law stipulated that a nun, regardless of her length of service in the order or her seniority title within her order, must pay homage to even a newly initiated monk. Acaryas of the medieval period developed a new set of monastic titles.

“The ranks for the monks became: (i) Sadhu or Muni, (ii) Ganivarya (iii) Pannyasa or Pravartaka, (iv) Upadhayaya, and (v) Acharya. The ranks of the nuns became to be recognized as “heads of the order.” [9] The fact that, for a long time in Jaina history only men were allowed to head the order was evident from the fact that young sadhvi Candanajia was given the title ‘ Acarya’ in its original form and not in any feminine form.

In assuming the title “Acharya”, instead of “Mahattara” – almost a non-title by now – both Candanaji and her guru Amar Muniji broke the tradition. They were, in effect, inviting the samgha to re-examine Mahavira’s message of equality. With Mahavira’s true message and history on her side, becoming an acarya was Candanaji’s act of self-assertion and defiance – a character trait evident in almost all her later activities.

Mahavira’s message of compassion (jiva-daya) was another issue, where she felt obliged to act. She felt that Jaina karma theory and the ascetic path were being misinterpreted. A Jaina ascetic takes five great vows (mahavratas)

as a personal commitment for self liberation. Since any action done is cause of bondage it was necessary to remain aloof from all non-essential activities. They advice their lay followers to take up compassionate causes but would themselves remain uninvolved in order to avoid “attachment to the cause, and its resulting karmic bondage.” Such interpretations have serious negative effects on social justice causes in a poor country like India. Jain laypersons generously donate to temples and support hospitals, animal shelters, schools and places of pilgrimage. However, a culture of physical and personal involvement as volunteers in humanitarian causes has not adequately evolved in the Jain communities, especially in the absence of direct involvement of their ascetics.

Candanaji was quick to recognize the seriousness of the lack of direct involvement by the Jain ascetics. She was aware of the globally evolving new concept of spirituality in terms of social justice, human rights and the rights of all the living beings – a concept that Mahavira preached nearly 2500 years ago.

“Personal salvation as well as upliftment of ordinary person’s mundane life is the mission of my initiation.” She repeatedly started pressurizing her guru to take on the social justice causes. Her guru, Upadhyaya Amar Muniji, in turn ordered her to undertake a very difficult and dangerous humanitarian mission. In 1973, Candanaji and four other nuns were asked to go to the remote areas of Bihar and help the poor. Bihar was then, and still is, the most poor, underdeveloped, and dangerous province in India. Twenty five hundred years ago, Bihar was the hub of Jainism; twenty-four Tirthankaras had once roamed this land and had achieved moksa in this region. Mahavira meditated for fourteen years in this land at a place called Rajgiri, and preached nonviolence, love and compassion. Now, however, there were hardly any Jain families in Bihar, and these nuns were to establish a humanitarian mission here called, ‘Veerayatan’. Initially Veerayatan met with very little support and considerable hostility from the locals. The mission, operating out of small funds, was vandalized, ransacked and looted several times in its early days, often endangering the lives of the nuns. Now, some 30 years later, the dedication and perseverance of Candanaji and her 10 Jain sadhavis has transformed Veerayatan into a leading Jain socio-religious organization. It operates a 200-bed free hospital, clinics, relief centers, a research institution and schools in Rajgir, and Pune. When the earthquake struck Gujarat in 2001, Candanaji and her nuns arrived on the scene within weeks and opened a school where nearly 6000 children get free education and meals.

Candanaji personally manages and supervises Veerayatan. Not only does she personally engage in its activities but also ensures that her nun disciples receive professional training in such fields as medicine, philosophy and business management, enabling them to get more involved in humanitarian work.

“All Tirthankaras have given this message through personal examples,” she contends, “they did not turn away from the society upon enlightenment, instead they dedicated themselves to the creation of healthy social values.” Her reform efforts are in keeping with the current global movement to rediscover true spirituality and redefine it in the terms of human rights and the rights of all living beings. Her reform movement has attracted worldwide attention from progressive thinkers, activists and youth. Nevertheless, she also continues to attract strong criticism, opposition, and heat from conservative Jains.

[1] J.C. Patni. The Life of A Saint, p.46.

[2]Ibid. ,p.

[3]Ibid. ,p.47.

[4] (Ed) Ram Mohan Das, Neeraj Kumar, A stroll in Jainism, p.xi.

[5]Ibid.

[6]Ibid. , p. xii.

[7]Ibid . , p. xiii

[8]Vastupala Parikh, Op. Cit. , p. 195.

[9]Ibid. , p. 196.

Feature Image Credit: wikipedia.org

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.