Abstract:

Hero’s Journey is a framework proposed and propagated by Joseph Campbell and is a widely accepted as a tool for transformation of self and its Narratives. The framework explores a 12-step journey of a “Hero” and works with external events and internal landscape. Joseph Campbell studied world mythology and acknowledged the rich foundations of the Hindu mythology. The Indian philosophical system especially Upanishad, Yoga Sutra and the Mahabharata views Hero as “DhIra” The one who experiences life fully anchored in a state of dhyAna and is therefore able to engage with life with great intensity. This way of engaging with life’s challenges frees the person from the cycles of life and death. The Journey of the “DhIra” as described in the Upanishads is similar to the processes of “returning to the source Consciousness” as defined in the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali through word-concepts like pratyAhAraandpratiprasava.

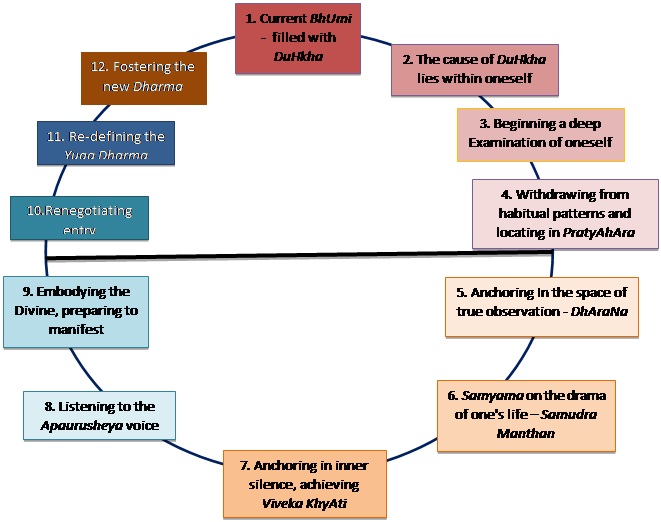

The authors introduce a framework based on Patanjali’s Yoga Sutra, Upanishads and Itihasa-Puranas that reflects the inner journey of the DhIra. The paper also examines the differences between the Yoga based framework and Campbell’s work.

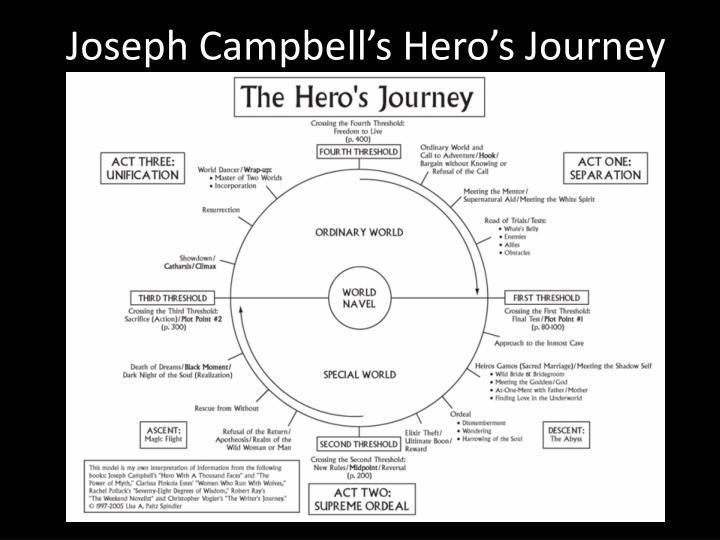

“The Hero with a Thousand Faces” was first published in 1949 in which Joseph Campbell[3]combined psychology with comparative mythology to give a universal motif of adventure and transformation. This framework became known as the “Hero’s Journey”, a popular tool for transforming self and its narrative. The framework explores a 12-step journey of a “Hero” and works with external events and the internal landscape. The framework is widely accepted and applied in various settings, from personal transformation to movies and building brands. The “hero” is anyone who transforms life the way it is through external adventure and internal exploration and comes back to the world with new gifts.

The proposition is that this is “monomyth”, a singular template for transformation all over the world. This proposition has been a subject of criticism from folklorists who have dismissed the concept as a non-scholarly approach to suffering from source-selection bias, among other criticisms. Toelken[4] writes, “Campbell could construct a monomyth of the hero only by citing those stories that fit his preconceived mould, and leaving out equally valid stories… which did not fit the pattern”. Christopher Vogler[5] in his “The Writers Journey”, has made some modifications to suit the modern rational temperament to this concept. He also brought down the journey down to 12 steps from the original 17 steps.

Another criticism of the framework came from Maureen Murdock[6] the author of “Heroine’s Journey”. It is said that when Maureen approached Campbell to discuss how the Hero’s journey differs for women, Campbell responded that women do not need to make the journey. The answer stunned her. Her experience as a therapist told her that women too struggled to move from the place they were at, they too were looking for a deeper transformation. Thus, came Heroine’s journey came as a map of the feminine healing process. Her map is of 10 steps and begins with separation with the feminine and integration of feminine and masculine.

The Indic Lens

Joseph Campbell studied world mythology and acknowledged the rich foundations of Hindu mythology. Anand Paranjape[7]in his study has shown comparative similarities between various streams of western psychology such as behaviourism, psychoanalysis and transpersonal psychology and the teachings of the Yoga Sutra. Yoga Sutra, as well as Upanishads, are texts of Indian philosophy as well as Hindu spiritual traditions. The mythology texts are both religious texts as well as considered to be maps of the inner psyche. Thus, from an Indic lens, mythology, philosophy, spirituality, and psychology all come from a singular base. The same sets of text cover a range of areas that the Western world treats separately.

The Indian philosophical system, especially Upanishad, Yoga Sutra and the Mahabharata, views a Hero as “DhIra”. A DhIra can be described as one who experiences life fully while being anchored in a state of dhyAna. A DhIra is, therefore, able to engage with life with great intensity and great tranquility. This way of engaging with life’s challenges frees the person from the cycles of life and death. The Journey of the “DhIra” as described in the Upanishads is similar to the processes of “returning to the source Consciousness” as defined in the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali through word-concepts like pratyAhAra and pratiprasava.

The Katha Upanishad[8] describes the story of Nachiketas. He is the DhIra, the one who sets out to discover the ultimate reality so that he can work in the world from that space of inner knowing.

Nachiketas – The DhIra

Gautama performed a sacrifice called Sarvavedas or Sarvadakshina, a sacrifice in which one is supposed to offer everything he has, without exception. It is a preparation for the last stage of spiritual life. However, he was not ready for it. He wanted to offer only things which were not valuable, thus following the letter of the law but losing the spirit behind it. He had a young son, Nachiketas by name, who saw the two defects in the sacrifice: the giving of weak and barren cows and the father’s ignorance of the fact that the son, too, was to be offered. “Joyless,” said the boy, “are the regions to which he goes who offers such sacrifices!” thus irritating his father.

The outer form of worship should be an expression of inner surrender and not a mere symbol. This is what Gautama’s sacrifice lacked. Desiring something, he performed the sacrifice but did not part with everything he had, as was required by its spirit. When this dakshina was given by Gautama, Nachiketas thought to himself:

“To whom do you propose to offer me?” (‘me’ also represents the self of Gautama). “If it is offering all, sarvadakshina, then it should include what belongs to one and his own self”.

Nachiketas asked this question three times. The answer was, “Unto death I offer you.” Though this was the answer to the son, it mystically means the death of the identity. Three times asked the boy, implying the ‘I’ has to be given up in three stages, not once. The first is the physical offering, followed by the subtle and the causal because we are this threefold being.

When Nachiketas reached the abode of Yama, Lord Yama was not there. Yama came after three days and, during that time, Nachiketas waited patiently. Yama says to Nachiketas: “O Brahmana, you have fasted in my house for three nights. I make obeisance to you! Ask from me three boons, for the three nights you starved here so that I may be blessed and do not incur the sin of not giving to my guest”. Nachiketas replied,

“As the first gift, O Lord, offer this to me: when I return, released by you to the world of my father, may he receive me with a calm mind, free from anger, recognising me as I have been before; not thinking that I am dead and returning.” This implies that Nachiketas must return, and when returned, should be recognised. He wants normal circumstances to prevail when he returns.

The second boon he asks for is knowledge of universal fire.

The third boon he asks for is “What happens to the Jiva when it reaches its final death—extinction of personality.

The desire for gold, the desire for sex and the desire for fame; these three bind the Jiva and prevent its further progress. Yama offered everything except Ishvara, intending to trick Nachiketas. However, Nachiketas met Yama’s ruse with equal strength of viveka and vairagya: the power of renunciation backed up by discrimination. Whatever be its glamour, everything is transient.

Nachiketas is a hero or the dhIra who is endowed with viveka, the power of discrimination, chooses the shreyas or the ultimate good. Therefore, he was granted the third boon.

The Hero’s journey then is to develop discrimination, viveka and move towards the ultimate good. Thus, from Indic perspective, DhIra is the one who, through their practice, cross the ocean of sorrow, reach a space of vivekakhyati and then operate in the world from Viveka. In the yoga Sutra[9] this is indicated in Sutra 2.26 and 2.27

sutra 2.26

viveka-khyAtiH-aviplavAhAna-upAyah

विवेकख्यातिरविप्लवाहानोपायः॥२६॥

Sustained discrimination and illumined comprehension are the way to end sorrow.

VivekakhyAti means understanding the distinction between puruSha and prakrti, having a discriminant understanding or perception of the world and understanding the true from the false. We must find a way to stay in this state of clarity where reality is seen as it is, without any fluctuations. What takes one to the conditioned forms of self is abhinivesha. Abhinivesha is the compulsion to grasp and hold the self’s mistaken identity (asmitA), which is reinforced by rAga and dveSha. Abhinivesha keeps reminding the person that one is alive and must live in a way that reinforces one’s asmitA. In vivekakhyAti, one does not need any evidence of being other than the moment of aliveness. This lucidity of perception is discernment and nirodhaH.

sutra 2.27

tasyasaptadhAprAnta-bhumiHpragnyA

तस्यसप्तधाप्रान्तभूमिःप्रज्ञा॥२७॥

Seven levels of lucidity lead to the ultimate wisdom.

It is said that there are seven steps for the achievement of clarity and being grounded in wisdom. The yoga sutra gives reference to seven steps, the final of which is the attainment of pragnyA– luminous state of perfect understanding. One moves from one state of clarity into a higher state when the earlier level becomes a bhUmi or an established level. The summit of this climb is kaivalyam, where having seen everything as it is, the self merges with Brahman.[10].

Of these, the first four steps are the ones where one can put effort to refine oneself. The intensity of the practice aided by the grace of the Divine takes the person further. This grace is known as is cittaprasAdanam.

- The first step is understanding the nature of avidyA. Realising that one is living in a way that ought not to be lived is called heyam (that which is to be avoided). One also realises that one is responsible for one’s predicamant. One begins to observe one’s actions and how they cause duHkha.

- The second step is heyahetu or having an insight into the causes of avidyA, and kleshA or impediments that are causing the sorrow. One begins to have insight into how the mind triggers action.

- The third level is having a clear glimpse of hAnam (seeing the roots of misidentification of puruSha and prakrti). This glimpse creates a yearning within, and one gets committed to a diligent practice.

- At the Fourth level, this yearning is converted into a discipline and a practice that will help one establish each level and sustain viveka khyAti (discriminant comprehension).

- This practice now has its inertia, and it will push one into the further stages wherein one receives grace. This practice can take one to the edge of clarifying all the residue in one’s buddhi. This limit is called “alingaparyavasAnam” (Sutra 1.45). One starts to dismantle the constructed self. The mind is cleansed of Rajas and Tamas.

- Steps 6 and 7 are intensifications of step 5. By constantly staying with the practice, a new samskAra replaces the old one. The vAsana (the seeds of avidyA) do not impede or touch the movement of pratyaya-perception that is lucid and untouched by avidyA. One gains visheSha darshanam, i.e., the clear perception of the nature of puruSha and prakrti; andkaivalyaprAgbhAram, i.e., the psyche gains the ability to carry the weight of kaivalyam.

- One reaches a state where there is no craving at all. puruSha can now ‘shine’ with its Intelligence. One reaches the state of ritambharA pragnyA (Sutra 1.49) (profound and extraordinary knowing) of and kaivalyam (Sutra 4.34) (transcendence).

Based on these two Sutra-s, we propose a framework as a map for the DhIra-s journey. This journey is not just of DhIra as an individual but also DhIra in the context of the collective reality. Much of Indian dance and poetry speak directly about the Nayika’s quest[11], the spiritual quest of the seeker. This follows the yogic framework very closely. There are two broad schemas we can start from. One is Shri Ganapati Sthapati’s[12] articulation of divine manifestation in the here and now, and the other is the Yogic framework related to dance.

Shri Ganapati Sthapatihas said – Shiva resides inside a cube and is completely at rest. This cube is the daharAkAsham (the space at the centre of the heart). The cube experiences a small imprint when one perceives a challenge from the outside. He calls this amzhithal – the formation of an indent. Then he says, it goes through a process called imizhthal – the impact is drawn into the cube. Then a process called kumizthal – energy is concentrated around the indent. As per Sankhya, amizthal – the external impact is the nitmittakAraNam (explicit cause) and kumizthal is the upAdAnakAraNam (implicit cause) that come together to create a response.

Sthapati then talks about a stage called umizthal – internal concentrated energy becomes the seed like prototype that will take a form. When this seed unfolds and emerges, he calls it thamizthal– emergence as beauty. The interesting thing is the kumizthal – the gathering of the internal energy in response to the challenge is replete with Beauty, Life and Truth if it touches the dancing Nataraja potential inside. If, however the kumizthal gets blocked from touching Nataraja waiting to express Himself, the intangible inner ground (upAdAnakAraNam) of avidyA is awakened. When upAdAna is filled with avidyA, then in the process of umizthal this avidyA forms the basic prototype- a deadening response replete with distortion and untruth.

The Yoga Sutra schema speaks of a process of cleansing the inner space; one’s upAdAna. This inner cleansing makes the inner space completely innocent of all distortion; this is called shudhasatvam– a perfectly pure inner space from which Nataraja manifests. {Tada drastuhsvarupe-avasthanam; vrtti-sarupyam-itaratra (Sutra 1.3 and 1.4)}[13].

We are bringing these two ideas together, namely, the seven steps enunciated in the Yoga Sutra and the five steps enunciated by Ganapathi Sthapati, in mapping the journey of the DhIra. Therefore, the Yogic map of a hero’s journey is to go within and clear up the upAdAna that is distorted with avidyA and causing duHkha for oneself and inducing actions that are adharma (actions that cause sorrow for oneself and one’s context and the world one lives in). This cleansing and the resultant shudhasatvam (mind like a perfect crystal) ensure that one’s acts are dharmic; one does not cause duHkha to oneself or the other. The divine potential residing within informs one’s responses to the world.

The Hero’s journey can be characterised as starting with the realisation that one is in duHkha and causing adharma – amizthal. It proceeds as the person turns inward and begins the process of ending avidyA that colours the psyche– imizthal. The endpoint of this inner travel is discovering the Intelligence/ Consciousness within and engaging in dialogue with It-kumizthal and preparing to manifest having soaked the Intelligence and becoming capable of reflecting Its light– umizthal. Finally emerging with the energy of Beauty, Life and Truth, (devoid of any sense of personal self)– tamizthal.

The DhIra’s Journey

Transcending the personal self and coming back to this world for the collective is the DhIra’s journey.

The 12 steps of DhIra’s Journey are:

- The current ground of living is not dhArmic. There is an experience of DuHkha that, despite knowledge, wealth & accomplishment, does not enable the overcoming of suffering within nor enables Dharma to flourish. Therefore, the current reality is not acceptable.

- There is an insight that one is experiencing the world and oneself through the veil of avidyA. This is causing DuHkha.

- The realisation that the cause of the DuHkha is within and not outside and recognising the inner structures that cause DuHkha. This leads to an enquiry “What is Dharma? What is kartavya?”

- The practice of observing the dynamics of the behaviour that leads to DuHkha in one self and adharma.

- Moving beyond the known into the space of true observation – sakhibhAva and sAkshibhAva.

- Watching all the dramatis personae of one’s inner space as they play out the Samudra manthan from the location of the meditator.

- Harmonising all the aspects of the self, dissolving of self-identifications, and ending the inner drama – anchoring in shAntam.

- Hearing the Divine voice. Letting go of all vestiges of the self and becoming the perfect vessel for Divine action.

- Reappearing from deep into the process of manifestation – The DhIra comes back to the world as the Divine energy that works through the DhIra.

- Renegotiating entry into the world– DhyAnajmkarma (action born out of meditative insight).

- Defining the new yuga dharma.

- Becoming the new Gardener – fostering and nurturing new ground

To recognise and practice these steps, we must have an understanding of avidyA which is the basis of DuHkha.

avidyA[14]

Klesha-s are residues that cause suffering, blockages, and pain. Klesha-s are the vritti-s (mental processes) that impact us and create “DuHkha”. They constitute the ground of avidyA that gives rise to the belief that this is who one is (Asmita) attachment, indulgence and craving (RAga); repulsion and avoidance (DveSha); and fear of death- the form of the identity that we hold on to (Abhinivesha).

avidyA is the kShetram (which means ground) in which the other four namely asmitA, rAga, dveSha and abhinivesha are present in the following forms. The first is the prasupta form – the latent seed sitting quietly, waiting to be born. This is the sancita karma (what will not show up in this birth) and prArabdha karma (that one lives through in the birth). tanu is the sprout; vichinna is intermittent; udAra is completely visible, fully grown form. This is the manifest level.

We experience suffering in tangible ways when the seeds of avidyA manifest themselves through action. These actions reinforce one’s own duHkha creating patterns of feeling, thought, and action and create adharma. When these seeds are in the unmanifest form, they generate unconscious compulsions and suppressed desires and fears. In this form, one may not act out in ways that are not dharmic but passively support or instigate them. The way a society valorises a person’s actions reinforces the choices they make. For example, today’s Hero is the entrepreneur who amasses wealth. The social and environmental impacts of his actions or his organisations are not questioned. This idea of wealth creation is a contemporary form of the colonising imperialist mind.

Mahatma Gandhi can be seen as a modern version of the DhIra. The Satyagraha that he led was dharmic and simultaneously the outcome of a personal search for truth. Others like Nelson Mandela followed his example and their lives are an exemplar of how they based their political struggle on an inner search and purification. Their private dairies and dialogues reflect the deep introspection they engaged with throughout their lives. In his book “My Experiments with Truth” Mahatma Gandhi discloses the klesha-s he has to confront within him and the courage with which he undertakes various practices to achieve inner clarity and purity. This disclosure continues through his life.

We will now look at the stages of the inner journey in greater detail as one that can be undertaken by any person who awakens to their duHkha and the way they reinforce adharma.

avidyA and the Hindrances

avidyA manifests itself at each stage of the inward journey. This starts from vyAdhi– illness and goes all the way to anavsthitatvam– acquiring the new capabilities but not anchoring one’s life in a new way and transforming one’s world. While describing each threshold of the journey, we are also taking recourse to the idea of antarAya as hindrances to be overcome at each stage of the inner journey. There is self-sabotage when they are not recognised or dealt with courageously, and the person aborts the journey.

Sutra 1-30:

vyAdhi-styAna-samshaya-pramAda-Alasya-avirati-bhrAnti-darshana-alabdhabhUmikatva-anavasthitatvAnicitta-vikShepAHte-antarAyAH

व्याधिस्त्यानसंशयप्रमादालस्याविरतिभ्रान्तिदर्शनालब्धभूमिकत्वानवस्थितत्वानिचितविक्षेपास्तेऽन्तरायाः॥३०॥

In the practice of Yoga, the sAdhaka (practitioner) often experiences blocks and obstacles. They are illness, inertia, doubt, carelessness, fatigue, over excitement, wrong perception, inability to build a foundation, or the inability to locate oneself in a bhUmi ground.

Stage 1 of the Inner Journey

The key motif for the inner journey of the DhIra is the famous proclamation in the Shrimad Bhagavad Gita “yada hi dharmasyaglAnirbhavatiBhArata”- whenever dharma declines in the land I will emerge.

The DhIra’s first realisation is “dharma glAni“- the lack of Dharma. We see this clearly in the story of Nachiketas. Suppose we narrow the idea of “BhArata” as one’s life space. In that case, each one of us can undertake the journey of the DhIra, and it begins with the realisation that one’s BhUmi is covered with the darkness of avidyA instead of being filled with light. The individual who is experiencing suffering tries out many strategies to end suffering. They seek refuge in people whom they feel are saviours; they seek refuge in material possessions, in seeking knowledge or through religious observances. Only when they see that these are temporary solutions do they realise the need for deep questioning and take responsibility for ending their sorrow. The stage is set for inward turning. Without this recognition, the individual lives with vyAdhi – illness and indulgence.

Stage 2 of the Inner Journey

At this stage of the inner journey, one needs to understand that some things are tangible and many things are not tangible. One tends to disown, leave untouched, and remains unaware of the intangible. The tangible and the intangible together comprise the self. The whole inner space from which one’s responses arise, the upAdAnakAraNa is where one must focus attention, not the external trigger. Typically, one acts from the asuric mind- something external is causing duHkha and sukha. One says to oneself “If I have enough power, I can capture sukha and keep away duHkha“. One then uses all one’s resources to create inner structures that can hoard sukha and guard against duHkha.

When one understands that the external only triggers something internal, the process of internal cleansing begins. The experience of duHkha and sukha comes from one’s upAdAna – the very inner structures that one is building, imagining that the source of duHkha comes from the nimittakAraNa – triggers that lie outside.

The process of kumiztahl – the gathering of associations, conclusions and assumptions that come in the way of Intelligence, form the upAdAnakAraNa called avidyAkshetram in Yoga. This ground generates erroneous knowing and, therefore, erroneous meaning-making, leading to actions that reinforce the errors.

The realisation that one has built a fortress on a very ill-conceived foundation could lead to a feeling that the road one must traverse to transform this “self’ that one has so carefully crafted is long and arduous. SthyAna – Inertia and a feeling of laziness can prevent one from taking this step fully and reversing the current cycle of living.

Stage 3 of the Inner Journey

The next step is realising that one is creating one’s world and creating one’s avidyAkshetram. Since one is responsible for sustaining one’s reality, one has to ask the question seriously “what is my dharmam, (actions that create wellbeing for me and my world) what is my kartavyam (my response capability and responsibility)?” These are the questions asked by Arjuna before the war: “dharmakshetrekurukshetreSamavetayuyutsavaha” that convert the theatre of war – the Kurukshetra into a theatre of action with a divine purpose- Dharma kshetra. When one asks this question with sincerity and intensity, one will always experience those intense reactions that Arjuna shows. We now know that these are symptoms of deep inner crisis when the autonomous nervous system gets disturbed. It happens because one is questioning the very ground of one’s being. However, when one asks this question, one can say to oneself: “I am creating my reality and I am now taking complete charge”. One then comes to that point when one says, “I realise that if I keep on acting from my current sense of knowing, I’m only going to create more and more of the same reality. I don’t know what to do!” The real seeking begins; one can listen anew, unlearn and discover how to dismantle the inner structures, and keep one’s inner space free.

The combined weight of inertia and lack of vitality can leave a person stranded at this threshold. It comes in the way of committing to the journey in the form of doubt (samshaya).One is unable to bolster up the conviction needed to say “Yes! I can walk the path of discovery.”

Stage 4 of the Inner Journey

When one crosses stage 3 unequivocally, one begins the process of pratyahara. One is not feeding the same old reality; feeding the old mind. One accepts that one does not know how to create the ever nascent, sensitive and aware mind. This is the point of surrender. It is not an action of falling at the feet of a Guru in dependency, holding on to one’s hopes and wishes. It is an act of courage where one lets go of the ground from which false aspirations grow. One realises that the life one has led so far where one has identified one’s sense of self and security with the outside reality is only feeding the avidyAkshetram. One is completely open to learning.

When one embraces the Indra moment, the ground on which one has been standing is shaken up completely. This is reflected in the beautiful story[15] that compares the mind of Indra and Virochana.

Prajapati decided to reveal a great truth to all the people in his world. He invited them into his great assembly hall and made a proclamation “The Atman is free from all stain and impurity. It is unaffected by change, it is immortal. It is free from every kind of grief and turmoil. It has no hunger or thirst. Its will is all powerful and its wishes are immediately materialised. This Atman is to be enquired into. Whoever discovers this Atman becomes one with the Atman.” The asuras and the devas both heard this proclamation. The devas chose Indra, their chief, as the right person to study with Prajapati. The asuras chose their chief, Virochana, for the purpose.

Indra and Virochana went to Prajapati and approached him as humble disciples. Prajapati was silent, and they waited for thirty-two years observing austerity and living a very disciplined life. Prajapati, having observed them feeling satisfied with their sincerity, gave them the knowledge they desired. “That purusha, the Being that you see in your eyes, that is the Atman”. Indra and Virochana concluded that they understood the statement. “We know what is seen in the eye. A body is reflected. That then is the Atman”— “Then, what is reflected in water, or in the mirror is that the Atman?” they asked. Prajapati said, “It is seen in every kind of reflection. Please go and look at yourselves in a pan of water and see what is there; if you cannot understand anything about the Atman, then let me know.” They went and saw themselves in a pan of water and the reflection, they saw themselves very clearly reflected. Prajapati concluded by saying “What you see in your eyes is the Atman. What you see in the reflection is the Atman.”

Indra and Virochana started their return journey thinking that their own body is the Atman. Virochana was overjoyed and had no doubts in his mind. He proclaimed this doctrine to asuras: “This body itself, what we see here, is the Atman. This is what Prajapati told us. This body is to be nurtured, adorned beautifully, made powerful and taken care of well. There is nothing more real than this body. The body is the instrument through which one can control one’s world.”

Indra was fraught with doubts as he trudged back to his home. “How can this body be the Atman? If the body is the Atman, it would be affected by every kind of pain, pleasure, desire and emotion which the body experiences. This body is also subject to death. There seems to be some mistake in my understanding of this teaching.” So, he returned immediately to Prajapati and related to him his deep misgivings.

Prajapati was overjoyed and asked Indra to undergo another 32 years of tapas and meditation. Indra was introduced to the idea that the dream world was the Atman. This, too, did not satisfy Indra. He went through another 32 years of intense contemplation. The mind of dreamless sleep is Atman he was told. Though this meant the end of all the activities of the mind, and the ending of the self that can be known and recognised, Indra was not satisfied. After another 4 years spent in dhyAna, the secrets of the Brahman that resides in the cave of one’s heart was revealed to Indra.

It is possible that one runs to somebody else, ask a teacher to tell one what to do, and hands over one’s responsibility to somebody else. This vacillation between becoming wholly responsible and accountable to oneself, and becoming dependent is a critical threshold to cross. At this point, one can play games- hold on to doubt, and ask the teacher to convince one against one’s conviction. One can hold on to new possibilities and keep testing them but never committing fully to the path. One does not say with conviction “Yes! I can and will undertake the search.”

With this step one is taking a step into the unknown and the unknowable! The familiar references and building blocks of knowledge, namely, externally validated conclusions, security derived from belonging, and worldly wealth and possession, are entirely useless. All meaning-making of the mind comes to nought since one is letting go of all markers and coordinates. One is at the threshold of one’s inner journey that has to be walked alone. This is when the heroic journey starts.

One is willingly leaving behind ideas of permanence, of acquiring knowledge and building defences against pain. One is also letting go of all false ideas of ‘self’ based on external identifications. This freedom can create a feeling of euphoria. One can become complacent (pramAda) and not realise that this freedom from the process of creating a reality of one’s own does not mean that one has built the new.

Stage 5 of the Inner Journey

The movement from step 4 to 5 is a significant threshold. When one has crossed step 4, one has made a fundamental shift. When one started this journey, one’s narrative would be either of a victim, helpless and blocked from self-expression, or one of rebellion where one fights the rules of society, or of obedience to the laws or of escape from these struggles. It will be a story of a person in the kurukshetra! When one takes step 4, one commits to authoring one’s own narrative, to stop energising the meanings of self and the world that are external to oneself.

This is a heroic step, and this will enable one to create a ground for action that is deeply meaningful and fulfilling. One will be capable of progressing to self-actualisation. The heroic action can also leave one feeling exhausted because acting from here requires much vitality.

Step 5 requires one to examine the ground from which feeling, thought, and action arises.

This is the beginning step of dhAraNa. According to Yogacharya Shri Krishnamacharya, dhAraNa starts with an observation of all aspects of one’s life: “How does my body function, how do I respect it? How do I relate with people? How do I relate with objects around me? How does the meaning making process arise? If I’m not able to respond with ahimsa, what is the inner state of ashuddhi?” So, every aspect of one’s life is observed with curiosity, compassion and rigour.

This intense observation leads to insight into the nature of self and the world. One would be able to energise one’s heroism. However, if this observation is not well grounded, this could lead to a regressive pull to go back to the world of fantasy. One could be attracted to creating a whole new internal reality. While this might be more meaningful than the one, one was stuck in before one started this journey, getting enamoured with this new formulation could become a form of indulgence (Alasya) that lacks vitality. It is a distraction from the discovery of the ground of all Being.

Stage 6 of the Inner Journey

When one lets go of the pleasure of discovery and converting it into a new skill in the world, one is ready to take the next step where the entire drama of one’s life gets revealed from its subtlest movements within one’s psyche to the manifestation in the tangible world. This is the place from which one is examining and experiencing the samudramanthan in oneself- churning the ocean seeking ambrosia. The story[16] is as follows

Once upon a time, Deva-s and Asura-s were in a long war. The Deva-s were also tired of fighting and afraid of losing the war. So, the devas approach Vishnu. Vishnu asks them to churn the ocean of milk along with the Asuras. Vishnu promised them amruta (ambrosia that made one immortal). The Devas went to the king of Asura-s and convinced him to join them in churning the ocean. Mount mandara was used for the churning, the great snake Vasuki to be the rope. First, a poison called halahala came up. Shiva drank it. Then many gifts showed up. Whatever Asuras asked for was given to them. Then came the amrita in a golden vase. The Asura-s tried to snatch it. To stave off the possibility of amruta falling into the hands of the Asura-s, Vishnu became Mohini, a beautiful maiden who promised to distribute it equally amongst the Devas and Asuras. The Asuras are so enamoured by Mohini that they did not realise that amrita was given to the Devas and nothing was left for them.

The living process requires one to move into the outer and return to the inner at every level: one eats food, and digests it; one breathes in and out; one takes in events around through one’s senses and go inwards to make meaning. The movement outward is also an experience of one’s power in the world, one’s uniqueness. The movement inward is a movement that dissolves all external identification and touches the levels of pure energy and pure mind. This inner level is beyond an experience of separateness, name and form. When one locates oneself in the process of dhyAna, the meta-process of creating meaning, creating a sense of self and then getting caught with ensuring the survival and growth of this constructed self is revealed. “When am I getting drawn into it the pleasures of life and when am I able to stay unentangled? When am I acting from forces of integration for myself, when am I distorting myself and fragmenting myself? So, when I am being the child of Aditi – the mother of integration, and when I am being the child of Dithi – the mother of differentiation? Any action that I do which causes entanglement with attraction and aversion i.e., rAga and dveshaH, I’m becoming a child of Dithi. I can act in a way that I’m integrating with my energy, I’m creating wholeness in me, I’m acting as Aditi’s child”.

As one moves towards the next threshold, one has to make this ground of dhyAna an anchor, an enduring location. The inner movement reinforces coherence and integration; the outer movement opens the possibility of a perception of the world that is lucid and devoid of any emotional charge. In the Mahabharata, this process can be mapped to the 12 years of self-reflection and sAdhana the Pandava brothers undertake. This is a period of deep introspection and self-discovery. The brothers dialogue with great sages and are also gifted with extraordinary powers when they transform themselves. However, there are times when the brothers lose patience and advocate impulsive action (avirati). Yudhishtra is the one who holds the patience and enables the full inner readiness to emerge.

As one watches the samudramanthan the seeds of avidyA are burnt and the sense of self is dissolved. Profound and extraordinary potentials called aishwarya begin to manifest. One is anchored in a discriminant attentiveness (called vivekakhyAtiavilplava in the Yoga Sutra) between the nature of the manifesting world and the nature of the life-giving energy that flows ever nascent from a deeper spring.

Stage 7 of the Inner Journey

When one becomes anchored in step 6 and move into step 7, there is inner silence; one is not engaging in the process of making personal meaning; One’s personhood has dissolved, the energies of survival and fear of death have ended. Yoga Sutra calls this pratiprsavaheyam[17]– the process that energises the recreation of a personal world ends completely. It reinforces the idea with another Sutra- visesa-darsinahatmabhava-bhavana nivrttih[18]– the one who has discriminated between the world of manifestation and the source of Life has no shadow of self. It is from this depth of silence and coherence that the aishwarya start to manifest. Because one can sit with the silence and watch this whole inner churning happening, the mind becomes very subtle; dhyAna progresses into samAdhi. One begins to listen to Intelligence; one can touch the source of Life within. The communication that happens here is through dream images and subtle inner movements since one is entering very subtle realms of self-close to buddhi. I can easily get trapped in the process of trying to understand and interpret these insights through the manas (the word-based aspect of the mind). The subtle messages cannot be translated into everyday language and this attempt leads to brAntidarshaNam – delusion.

When kumiztahl at this level of dhyAna and samAdhi is not touched by the shadow of avidyA (brAntidarshaNa), one can clearly hear the voice of apurusheya, the Unborn Intelligence. One can now reside in atmabhava-bhavana nivrttih a space filled with Life and Light.

There is still the process of creating a stable foundation for the new and transformed self to be shaped. This hindrance is called alabhdhabhUmikatva. Once this is crossed, the foundation on which a new self evolves becomes firmly established. There is no more regenerating of the personal self, no regenerating of avidyA, no regenerating of the whole process of creating attractions and aversions. One acts from Intelligence with no pull or possessiveness towards the fruits of the action.

In the Mahabharata, the one year that the brothers spend in agnAtavAsa– live incognito is when each one has encountered their shadow selves. Primarily Arjuna, the dhIra explores his feminine side by being a female dance teacher for the princess. That prepares him for the complete transcendence of his identity. Before they go into this phase of their inner transformative journey, the brothers have to wrap up their great weapons in skin and hide it. They can claim it again only after they have dissolved their shadow selves and created a new ground of self-anchored in dhyAna. A profound transformation happens at every level of one’s psyche and soma. This is called prakrtiApuraNam[19]– complete transformation. The sense of self is dissolved, one is no longer authoring one’s personal story; one is an actor in the Divine narrative.

Stage 8 of the Inner Journey

Yogacharya Krishnamacharya would constantly say that in Kaliyuga, to know what is Dharma and adharma, one has to go into themselves and hear this divine voice. He referred to this experience as atmatushti. When one comes to this point of listening to apaurusheyam, and one hears this voice, one starts the journey of manifesting in the world as a form that reflects Divinity.

Anandam– bliss can be experienced only when all the sense of self is lost, and there is atmatushti. Yogacharya Krishnamacharya would then compare this state to the verse from Taitriya Upanishad – AshisTodradishTobalishTaHsaekomanushaAnandaH: This is a person who is in his prime of life. He has all the power; he is a mature, healthy person who can experience the navarasas without any distortion at all; there is no shadow of self to distort the flow outward, nor to create residues as one move back in. This person’s engagement with the world is replete with Intelligence and Love. Therefore, he is experiencing this Anandam.

The madhurarasam starts, i.e., experiencing all life in its essential beauty and sweetness. One has moved from duHkham to madhuram. The Yoga Sutra uses the term ritambharapragnya – knowing replete with Truth, to describe this state.

There is an interesting story of Parvati and Shiva: They were in a great state of sensuous delight on the mountain, enjoying the pleasures of life. While the seasonal changes, the climate and the place doesn’t affect Shiva, it affects Parvati. Shiva jokes with Parvati and says to her “I am a yogi; I am beyond all these changes; they do not affect me. I had warned you before you fell in love with me.” She says to him, “Take me to a place where I am not affected by all this. I am not able to handle the extremes”. “While marrying me, you knew that I am an Andi – a poor Yogi with no possessions, I don’t have a house, no money nothing. I’m just happy wherever I am. You knew that when you came to me” replies Shiva. Parvati laments “Now I know that I cannot survive in this”. So, Shiva laughs, picks her up and takes her above the clouds. The story says so many things: the masculine and feminine intertwining within oneself and finding total harmony, just as the outside and inside flow with complete ease. There is a point where Shiva and Sati have to move above the avidyAkshetram for the experience of Anandam.

This story also illustrates many other Sutra-s sthirasukhamAsanam; tatodvandvaanabhighAtaH[20]. Moving above the clouds has got lots of other parallels. I moving into pure space Akasham, I am going past the cloud of all possible manifestation and that’s the beginning of all manifestation.

While one discovers the ability to reach this state of being, it takes persistent effort to convert it into a ground of being. Without this consolidation, one encounters the hindrance called anavasthitatvam.

The Yoga Sutras speak of gurushikaram as the process of dissolution of the self-constructed with the rajasic and tamasic aspects of prakrti. The complete dissolving of these structures at the very foundation is called astham, and the mind in this state is called shuddasatvam – buddhi cleansed of all avidyA. Then one becomes kaivalya pragbharam– capable of bearing the weight of total liberation. This results in a complete transformation of the self in all its aspects of manifestation called prakrtiApUraNam. One has a complete insight into how prakrti transforms itself, manifests, and returns to the original unmanifest state. This lucid and acute perception is called pragnya.

The Pandavas go through the whole process of inner transformation in their 12 years of penance and one year of agnyAthavAsam. The agnAthavAsam symbolises the time when all their shadow sides are thoroughly transformed. The Pandavas are then allowed to reclaim their great weapons. Only after this total cleansing, the Pandavas become really capable of being heroic and ruling the land with new dharma.

The Yoga Sutra-s recommend a deep enquiry into pratipaksham[21]– motivations like greed, envy, lust and so on. Then the process of complete turning inward called pratiprasava- going back to the Origin and anchoring oneself in Consciousness proceeds unhindered. The five brothers and Draupadi, their feminine counterpart, have to live separately; they cannot help each other or even talk to each other. They give up privilege completely and become the opposite of who they are in society; they become servants. Moreover, most importantly, they take on an engagement with the world through precisely those parts of themselves that are compulsive and pull them into acts of adharma or indiscretion. Arjuna gained the pAshupatham, gANdivam and other weapons that symbolise extraordinary power through years of tapas. However, he (and his brothers who gained their excellent skills) could regain the adhikAram – the worthiness and legitimacy to wield them only after Arjuna and his brothers went through agnyAthavAsam.

In complete ekAntham- aloneness and deep introspection, one has cleansed oneself thoroughly and burnt every seed of avidyA, that is astam. The last hindrance called anavasthitatvam – losing the anchorage in the “here and now” is crossed. The shadow aspects of the self that bubble up unbidden and surprise the person are fully dissolved.

Without confronting the shadow and dissolving it completely, the new ground of action is not secure. One can fall back on the gains and insights received through traversing stage 7, hiding or managing one’s shadow sides and still acting in potent and heroic ways.

Stage 9 of the Inner Journey

Stage 8 is the point of time when Arjuna becomes capable of listening to the voice of Shri Krishna. The two have been friends for a long time; the other Pandavas also respect Shri Krishna; however, it takes the intensity of an imminent catastrophe to awaken Arjuna and enable him to listen completely. His brothers are great warriors stuck in stage 8 in a manner of speaking. They are extraordinary men, but they have not travelled to the stage when they can become transformed into Divinity. Arjuna questions every aspect of himself and his comprehension of life through the meditative conversation he has with Shri Krishna. When he emerges out of the dialogue he extinguishes even the most remote possibility of rekindling of avidyA. This stage is also called atItam. The spontaneous responses that arise from Arjuna will differ from his brothers, which is based on Dharma. The Kaurava brothers do not realise that they cause duHkha to themselves and the world. They do not go through any form of self-reflection. They use their immense powers in self-centered and adharmic ways.

In the Yoga Sutra the state achieved by Arjuna is referred to as karma-ashukla-akrshNamyoginaH-trividham-itaresam[22] the actions of a Yogi arise from a space beyond black, white or grey unlike others who act from propensities that are black (adharma) white (dharma) and mixed. In the face of great challenge, the Yogi’s actions will be spontaneously dharmic and reflect the Divine. This is the new bhUmi, an unshakable ground from which one’s life will be shaped. Like a finely tuned Veena or a drum that will produce sweet music when struck, one will meet any challenge with Intelligence and impeccability. An Arjuna who is merely intellectually convinced or even partly transformed will not be capable of a spontaneous response that arises in Intelligence. At best, the action will be a mixture of some flashes of insight mixed with one’s own best potentials like his brothers. At worst, it will be an action grounded in avidyA, envy, greed and fear like Duryodhana and his brothers.

So now one is ready to manifest in the world but in a new form, constantly renewing itself; one where the flow of prANa is completely collimated and coherent as a laser beam. There are no hindrances to living a life replete with Light and Love, however, there is a possibility that one decides not to re-enter the battle ground of life, and one retreats into this state of bliss. The Buddhists invoke the idea of a bodhisattva- one who has crossed over, but re-enters life because they feel infinite compassion for those who are caught in the other bank of duHkha. They go into the world of samsAra– the worldly cycles to awaken people and help them to transform themselves. The Buddha too is said to wait on the bank so that all the sentient beings of his time can cross over with him.

Stage 10 of the Inner Journey

Yogacharya Krishnamacharya says that Atma can take on masks, which are various forms of prakrti to engage with the world. He compares it with an actor on the stage who wears different masks to portray different characters. The puruSha wears different masks for action and enjoys this whole process. This is lila. A Yogi who is acting from ashuklaakrshNam – is beyond the pale of avidyA based meaning-making can wear the masks as appropriate and take them off at the instant when the need has passed. However, if one has avidyA lingering on, the mask sticks on to one’s face, one grasps asmita as it were. avidyA and abhiniveshaH are the glue. The ability to don the mask appropriate for the context, and let Divine Intelligence act, and take it off instantly is sanyAsayogam. The idea of a sthitapragna[23] captures this beautifully. A sthitapragna is aware from the subtlest to the most gross level of the drama being played out around him. Being aware of the tangible, the intangible and the knower- vyakta, avyakt and gna the actions of the sthitapragna are dharmic and appropriate. The sthitapragna can take on any identity as it is necessary and drop it, knowing that it’s a mask. The awareness, the choice of action and the repose are all grounded in shAntam.

The shuddhasatva mind, one that is shAnta rasa is like a white canvas. All the other colours show up brightly when one paints on it. But eventually if one does not clean the canvas, and get back the pure white, it gets muddy. The Hero is anchored in shAnta rasa acts with intensity as appropriate and regains shuddha satva. Thus, his preparation for action is donning the right mask/ armour and having the ability to dissolve them totally.

Stage 11 of the Inner Journey

From here, one is now ready to enter the stage of action. Since the world is a shared space, one renegotiates one’s entry into the world. One establishes a shared context, deeply internalises the dharmic ground of the action, and acts with complete conviction. At this step, one really discovers one’s Asanam-all one’s energies are fully embodied, one is fully seated in one’s body as it were, prakrti is coherent, all its prANic energies are convergent and centered in purusha. Shri Desikachar has said that when one achieves this level of clarity and cleansing of avidyA, one’s prANa becomes very dense and completely held within the body. Action that springs from here is called dhAnajam karma -action born out of dhyAna. When there is duHkhamprANa is dispersed outside the body and incoherent within. One’s actions are karmajam karma – action born out of a desire for self-centered outcomes. dhyAnajam karma is nishkAmya karma.

One is a karma yogi. One gives without seeking obligation, one acts without any benefit, one rests in profound shAntam.

The dialogue and negotiation with others in the context are with the intent defining the new yuga dharmam. One must not forget why one started this journey: “I was in duHkha, I realised that my context reinforced ways of being that resulted in duHkha, I also realized that I am responsible for being mindlessly part of this context. I now return with the intent of letting Intelligence act through me and establish a new way of being, of collaborating and using the resources of Nature”.

So, the dharmic negotiation is really not about the rest of the world, but that part within each of us that is hurt, that is caught with compulsions and is unable to dissolve the fear of letting go of the self that one has constructed. One needs to finish with one Ravanas, finish with one’s unique version of Duryodhana and Karna.

Stage 12 of the Inner Journey

Now one comes back and define a new dharma: A yuga dharma outside and one’s Dharma within. One starts defining, entering into dialogue, creating the context, removing obstacles and building the new. When one initiates the new Dharma, one cannot push people into doing what one wants. One must understand nishkAmya karma. One has to seed the new in many hearts and nurture it and see how it emerges.

One becomes the new Gardener. One assesses the soil, decides the right seed to plant, prepares the soil, plants the seed and nurtures it till it flowers and fruits. At no time does the Gardner impose his/her will, nor tries to possess the fruit.

The new Gardener is in charge of nurturing the dharmic ground. When the new garden blossoms, it will be tamizthal – an emergence replete with beauty. So the Ramarajyam, Dharmarajyam of the Pandavas are all tamizthal.

Conclusion

The inner journey of a DhIra is not a narrative of accomplishment. It is a narrative of a search for the origination of Life, for the eternal fountain of Love and the ultimate source of Light. When one is anchored in this primal Consciousness, engagement with one’s world takes on a quality that is fundamentally different from the “normal” ways. One becomes the vessel through which Intelligence acts.

When one awakens to the reality of duHkha, one realises that one has no agency. One’s actions are “choiceless” and arise from inner compulsions triggered by external agents. As one begins the process of introspection and inner discovery, one discovers agency and exercises choice. The ability for discriminant perception grows. Every choiceful and discriminant action is a step in the inward journey and is accompanied by an insight. One cast off all meaning-making and choice-making that is not integral to oneself. Finally, every vestige of “self” is dissolved. The inner space is filled with a profound silence, a silence in which puruSha is. One is anchored in “choiceless awareness of what is” and all action that arises from this silent centre of being is replete with Consciousness. The DhIra is one who has dis-covered all the layers of self that have veiled the puruSha, therefore, the action that arises from this profound Intelligence is dharmic. It dispels adharma just as light dispels darkness.

In Campbells framework the call comes from outside – a challenge, a disaster, an invitation for adventure. In Indic framework the call comes from within. The adharma one experiences is not acceptable and so the DhIra sets out on adventure. The Hero encounters the mentor outside, the DhIra encounters the sakhi, the beloved friend who connects the DhIra to the Source, the Divine energy inside. The Hero comes back with gifts, the DhIra comes back anchored in Consciousness and filled with Wisdom.

Further Reading

Campbell J (2008) Hero with a Thousand Faces. Novato: New World Library

Desikachar TKV (1999). Heart of Yoga. Rochester: Inner Traditions International

Murdock, Maureen (1990). The Heroine’s Journey: Woman’s Quest for Wholeness. Boston: Shambhala Publications.

Raghu Ananthanarayanan (2016). Leadership Dharma. Chennai: Productivity and quality Publishing

[1]Raghu Ananthanarayanan; B Tech Mech (IIT Madras) MS Bio medical Eng (IIT Madras). Disciple of Yogacharya T Krishnamacharya and TKV Desikachar; Co-Founder and chief Mentor Ritambhara Ashram & Co-Founder Sumedhas Academy for Human Context; Kothagiri, India. He is also the Director of Coaching for Inner Transformation.

[2]Dr. SanjyotPethe is a leadership development consultant, a coach, Somatic Experiencing practitioner and a story teller. She is a student of Yoga Sutra under Raghu’s guidance and conducts small sessions working with Purana Stories.

[3]Campbell J (2008) Hero with a Thousand Faces. Novato: New World Library

[4]Toelken, Barre (1996). The Dynamics of Folklore. Utah State University Press.

[5]Vogler, Christopher (2007) [1998]. The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure For Writers. Studio City, CA: Michael Wiese Productions.

[6]Murdock, Maureen ( 1990). The Heroine’s Journey: Woman’s Quest for Wholeness. Boston: Shambhala Publications

[7]Paranjpe, A.C. (2019). The foundations and goals of psychology: Contrasting ontological, epistemological and ethical foundation in India and the West. In K.H. Yeh (Ed.), Asian indigenous psychologies in the global context (pp.69-87). Cham: Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

[8]Swami Krishnanand. Katha Upanishad. Divine life society

[9]https://yogasutraforinnerwork.wordpress.com/

[10] The explication of the detailed meaning of this sutra is based on the discussions Raghu Ananthanarayanan had with Yogacharya Krishnamacharya and Shri Desikachar in 1980.

[11]The understanding of the parallels with dance are based on the discussions Raghu Ananthanarayanan has had with Jyothsana Narayanan in 2019. Jyothsana Narayanan has taught dance in Kalakshetra for many years and was a student of Shri Desikachar for more than 3 decades.

[12]The explication of the ideas from Vastu Shastra is based on the discussions Raghu Ananthanarayanan and Sashikala Ananth had with Shri V Ganapati Sthapati in 1982

[13]https://yogasutraforinnerwork.wordpress.com/2018/06/21/sutra-1-3/; https://yogasutraforinnerwork.wordpress.com/2018/06/28/sutra-1-4/

[14]https://yogasutraforinnerwork.wordpress.com/2019/04/04/sutra-2-2-sutra-2-3/#2.3; https://yogasutraforinnerwork.wordpress.com/2019/04/11/sutra-2-4/

[15]Chandogya Upanishad. Swami Krishnananda, Divine life society

[16] Subramanian Kamala (2017). Shrimad Bhagwatam. Mumbai: Bhartiya Vidya Bhavan

[17]https://yogasutraforinnerwork.wordpress.com/2019/05/16/sutra-2-10/

[18]https://yogasutraforinnerwork.wordpress.com/2020/10/15/sutra-4-25/

[19]https://yogasutraforinnerwork.wordpress.com/2020/07/09/sutra-4-2-sutra-4-3/

[20]https://yogasutraforinnerwork.wordpress.com/2019/10/24/sutra-2-46-2-47/; https://yogasutraforinnerwork.wordpress.com/2019/10/31/sutra-2-48-2-49/

[21]https://yogasutraforinnerwork.wordpress.com/2019/08/29/sutra-2-32-and-2-33/#2.33

[22]https://yogasutraforinnerwork.wordpress.com/2020/07/30/sutra-4-6/#4.7

[23]Shrimad Bhagavad Gita- Verses 55 to 59 of Chapter 2

Feature Image Credit: istockphoto.com

Conference on Hinduism and Modern Psychology

Watch video presentation of the above paper here:

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.