Abstract

The Indian tradition has always revered the Bhagavad Gita as a text of marvelous universality with the ability to throw light on many aspects of an individual’s life journey. Further, its importance is underscored by its preeminence as a source book of Indian Psychology. Indian Psychology is a modern appellation given to the extraction, compilation and consolidation, from Indian sources, of the principles of psychology based on the framework of concepts and categorization of the western tradition of psychology.

This article examines the deep insights into the human psyche as presented and intuited from the Bhagavad Gita and tries to consolidate them into maxims (Gita Suktas). It also examines the psychology in Advaita Vedanta – which is one of the windows of interpreting the Bhagavad Gita.

The generic principles and particular Advaitic principles of Indian Psychology as seen through the lens of the Bhagavad Gita are then studied in apposition with the principles of modern psychology. This study would yield an interesting set of observations about (1) the common ground between the two disciplines, (2) what Indian Psychology could learn from Modern Psychology and (3) the unique insights that Indian Psychology offers which could contribute to a better understanding and handling of human existential crisis and its resolution through better informed existential quest.

In an attempt to give a practical orientation, the article will examine briefly the principles of Indian psychology that influenced the life of three national leaders who have publicly acknowledged their debt to the Bhagavad Gita, having been life-long students of the text viz. BG Tilak, Sri Aurobindo and Mahatma Gandhi. The uniqueness of their personality/leadership will be correlated to the Bhagavad Gita’s unique repository of the Principles of Indian Psychology.

The Bhagavad Gita as the epitome of Indian Psychology vis-a-vis Modern Psychology

The traditional view of the Bhagavad Gita regards it as one of the PrasthanaTrayi – the three-fold scriptures of Hinduism, the other two being the Upanishads and the BrahmaSutra.[1] Of these the Bhagavad Gita is most widely read and translated. It has been translated into Indian languages (1412 translations), into English (273 translations) and other languages (191) translations.[2] Radhakrishnan regards the Bhagavad Gita as “a religious classic than a philosophical treatise ….. And that it is a powerful shaping factor in the renewal of spiritual life and has secured an assured place among the world’s greatest scriptures.”[3]

Psychology was born as a separate discipline in the late 19th century. The early 20th century commentaries on the Bhagavad Gita by Besant & Das (1905), Aurobindo (1928) and Tilak (1935, English translation) contained no references to psychology at all. The credit for the first exposition (in 1928) of the Bhagavad Gita on the basis of “psycho-philosophy & psychoanalysis” goes to Dr. V G Rele, a doctor-surgeon by training and a keen researcher of Indian Scriptures.[4] Professor Jadunath Sinha has many references from the Bhagavad Gita, amongst others, in his three volume comprehensive survey on Indian Psychology published in 1933. And thereafter, there has been a steady stream of research articles and books based on the psychology in the Bhagavad Gita until this day. Professor R. Ramakrishna Rao, the doyen of Indian Psychologists, recently published (in 2019) his psychology-based rendering of the Gita with a focus on its implications for counseling.

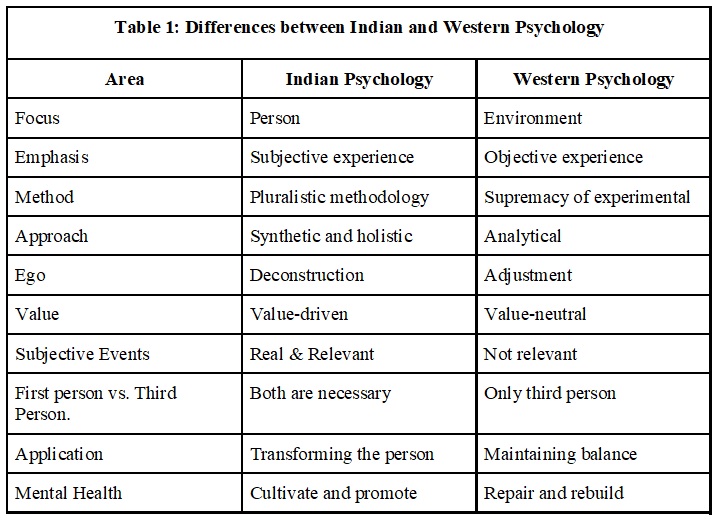

Before examining the psychological insights from the Bhagavad Gita, a quick look at Indian Psychology and how it differs from Western Psychology is useful. The following table[5] summarises the differences:

Swami Akhilananda’s astute observation, made in 1948[6]: “It is our opinion that Hindu psychology is more dynamic as it trains the individual mind to manifest all its latent powers….Hindu psychologists are primarily interested in the study and development of the total mind rather than in the different functions considered separately…The experimental psychologists of the West are interested in particular phases of mental activity.”

Swami Akhilananda’s astute observation, made in 1948[6]: “It is our opinion that Hindu psychology is more dynamic as it trains the individual mind to manifest all its latent powers….Hindu psychologists are primarily interested in the study and development of the total mind rather than in the different functions considered separately…The experimental psychologists of the West are interested in particular phases of mental activity.”

So what are the psychological insights (through the viewpoint of Advaita Vedanta) that the Bhagavad Gita has to offer about human nature that have obviously stood the test of time and continue to be significant? I present below the meta-theory of Indian Psychology and I acknowledge with humble gratitude the pioneering work of Rao & Paranjpe in distilling these features. I have also attempted to correlate these features with appropriate verses of the Bhagavad Gita.

- Psychology is the study of the person (jiva). (BG-15.7)

- The person is a composite of consciousness, mind and body. (BG 3.42)

- Consciousness, as such, is irreducibly different from material objects, including the brain and the mind. (BG-2.23-24-25)

- Unlike consciousness, mind is physical, though subtle, and is subject to physical laws. (BG 7.4)

- Mind does not generate consciousness, it reflects consciousness. (BG 7.12)

- The mind-body complex is the instrument of one’s thought, passion and action. (BG 3.40)

- The mind is different from the brain. Unlike the brain, the mind is subtle in form and composition; and as such, it is non-local in the sense that it is capable of functioning without the normal space-time constraints. (BG 13.1)

- The mind in association with the brain and body becomes conditioned and is consequently constrained and driven by bodily factors. (BG 15.8-9)

- The prime manifestation of the conditioned mind is the ego (ahamkara). (BG 7.4,13.4-5, 15.10)

- The conditioned mind is so biased that the truth it seeks gets clouded and even distorted; knowing in human condition becomes fallible and behavior of the person becomes imperfect. Mind itself becomes an obstacle, if the human quest is for truth and self realisation. (BG 6.18)

- Mind holding the reins, the person becomes the knower (jnata), the doer (karta) and the enjoyer of the fruits of her actions (bhokta). The mind in its agentic function acts as the self. It is behind the empirical self as distinguished from the self, atman or purusha, which is consciousness as such. (BG 18.18)

- The person in search of identity misconstrues the mind as her true self and hypostatises the ego function as the enduring self. Consequently self-gratification replaces self-realization as the goal of one’s endeavour. (BG 16.12)

- The mind may be functionally distinguished into three components buddhi, ahamkara and manas (BG 3.42), ( BG 7.4, 13.5-6, 15.10)

- Buddhi which is commonly translated as the intellect, is an essential and core component of the mind. It is sattva at its best in the human condition. Uncorrupted it is almost like consciousness. It has the ability to reflect consciousness in its purity. Buddhi is the seat of discrimination and creative action. It is also a seat of memory (sometimes separately called chitta/smriti) and a depository of karma and storehouse of samskaras and vasanas, unconscious complexes and instinctual tendencies. (BG 18.31-32-33)

- Ahamkara creates the ego sense. It manifests as the ‘me’ in each person. Identity is its defining characteristic. It is a source of distinction between the self and the other. (BG 3.27)

- The manas is like a central processor. Attention is its defining characteristic, filtering and analysing its other functions. It also acts as an internal sense organ.(BG 6.12,15.7)

- The mind in its totality (Buddhi+Ahamkara+Manas+Chitta) is the interfacing instrumentality that is connected at one end with the brain and bodily processes of the person with which it is associated. At the other end, the mind is poised to receive the light of consciousness.

- Thus, the mind is (a) the surface that reflects consciousness, (b) the ground from which the contents of one’s cognition spring, (c) the seat of egoism and (d) the storehouse of past actions and their effects. Because of such complexity the reflections of consciousness in the mind are subjected to bias, distortion and misinterpretation.

- The entangled mind becomes unsteady and distracted. Exposed to the incoming stimuli in the form of sensory inputs , excited by internally generated imagery, and conditioned by samskaras and vasanas, the mind is constantly in a state of flux and is unsteady and prone to turbulence and tension. (BG 6.33-34)

- In one’s quest for truth and perfection in being, there is therefore the basic need to make the mind steady and turbulence-free. This can be done by disentangling the mind by systematic deconstruction of the ego. (BG 6.35-36)

- There are several ways of doing this. One way is practice of yogic meditation which results in focussed attention which inhibits distractions. Practice of meditation (abhyasa) needs to be accompanied by an attitude of dispassionateness (vairagya). The practice of concentration (abhyasa) and the cultivation of vairagya (dispassionateness) are the twin principles guiding the practices of yoga to tame the mind and make it steady. Other ways of deconstructing the ego include self-surrender by practicing of divine love and devotion (bhakti) and action without attachment to results (nishkama karma). (BG 13.24-25)

- When the mind becomes steady and the ego is under control, the person tends to be less biased and be in a position (a) to come closer to truth, (b) experience consciousness as such, (c) narrow the gap between knowing and being, and (d) have access to a variety of hidden human potentials.(BG 15.5)

- The mind in the Indian tradition is the vehicle of one’s journey from the ordinary to the extraordinary states of experience, from rational thinking to creative excellence in knowing to transcendental realisation of being, from mundane to moral and from samsara to spirituality. (BG 6.5-6)

- The senses in the Indian tradition are considered more than the physical instruments or the physiological organs. The senses register the energy patterns emanating from the world of objects and reflect them on to the manas. However, it is manas that triggers the cognitive process. (BG 6.24)

- Manas has dual functions- (a) it processes sensory inputs and (b) acts as the sixth sense and receives inputs from internal states. (BG 15.7)

- Understanding the nature and function of the indriyas is necessary for gaining control over them. Appropriate control of the functioning of the indriyas is helpful (a) to achieve excellence and (b) to reach transcognitive states. (BG 2.67-68)

- Meditation in its various forms is helpful to gain control over the sensory processes. (BG 6.12)

- Just as the mind is a source of human suffering and also a resource for achieving bliss, so too are the senses. In their proper utilisation lies human happiness. (BG 3.34,17.16)

We see that the Bhagavad Gita delivers with surprising modernity and universality, a comprehensive picture of the human personality along with minute guidance for enabling a person to overcome existential crisis & anguish with the time- tested certitude of success.

Common ground between Indian Psychology and Western Psychology

The prima facie objectives are similar i.e. to study the human mind, psyche, human behaviour. However, the supererogatory objective of Indian Psychology (as intuited and understood from the Bhagavad Gita) is perfection of existence and moksha; while similarly though less grandly for Western Psychology, it is mental health and solutions to practical human problems.

What Indian Psychology can incorporate from Western Psychology

Some areas of Indian psychology are eminently suitable for experimental research. Meditation research is a case in point. There is voluminous experimental data collected under controlled conditions which include investigation of neurophysical correlates of meditative states, influence of meditation on cognitive and other kinds of skills and benefits of meditation on human health and wellness.

There are also other methods of modern psychologists that have relevance to Indian psychology. These include field studies and observations of naturally occurring events. The techniques include surveys, questionnaires, interviews, rating scales, participant observation and content analysis. Another method that has been successfully put into practice is the single-case study. We will use this method to study the impact of the principles of Indian Psychology in the lives of BG Tilak, Sri Aurobindo and Mahatma Gandhi later in this article.

What Indian Psychology offers

Consciousness is the key concept that distinguishes Indian Psychology from all other psychologies. The key to understanding a person is consciousness. (BG 10.20). Unfortunately, consciousness as conceived by Indian Psychology has no room in psychology as studied today or is considered beyond the scope of the subject. Accepting this concept would enhance the scope of current psychology.

A very brief exposition is presented below about the impact of Indian Psychology as epitomised in the Bhagavad Gita in the lives of Lokamnaya Tilak, Sri Aurobindo and Mahatma Gandhi.

Bal Gangadhar Tilak

Tilak was one of the great leaders of India in the struggle for independence. He was a public intellectual, journalist and scholar. It is during his imprisonment in Burma (Myanmar) that he wrote Gita Rahasya a scholarly commentary on the Bhagavad Gita aimed at explaining its secret (rahasya). It is in this work that he interprets the basic principles of Karma Yoga.

Tilak strongly believed in the Karma-Yoga-Sthithprajna[7] model from the Gita as relevant in practical life with a spiritual focus. The following sentence from Gita Rahasya says it all:

“Ideally a person should attain inner calm by purging the mind of all desires through the realisation of the identity between the self and Brahman. One should thereby attain equanimity, and malice towards none. Upon attainment of such a state one should set an example for others through one’s own behaviour, and help everyone around oneself in attaining spiritual progress.”

This is what Tilak preached and practiced throughout his life. Two incidents exemplify his character. When he was sentenced to 6 years imprisonment in 1908 and when a friend remarked that he would soon be taken to jail, Tilak is reported to have casually remarked, “What difference would that make? The British have already turned the whole nation into a prison. All they will do is to send me to a different cell in the same prison.”

When his eldest college-going son succumbed to plague, Tilak remained unmoved and remarked to his son-in-law: “Is it not natural, after all, that we would lose some firewood when the whole town is up in flames.”

Sri Aurobindo

Sri Aurobindo’s life and philosophy have many facets – militant, terrorist, extremist, revolutionary, and spiritual. His association with revolutionaries who plotted a bomb blast led to his imprisonment in Alipore in 1908. While in jail he had a series of deep spiritual experiences about which he spoke in the famous Uttarpara Speech where he said: “Then He placed the Gita in my hands. His strength entered into me …..I was not only to understand intellectually but to realise what Sri Krishna demanded on Arjuna and what He demands of those who aspire to do His work, to be free from repulsion and desire, to renounce self-will and become a passive and faithful instrument in His hands…..” [8]

One result of the realisation was the centrality of the Bhagavad Gita in all of Aurobindo’s writings.[9] Sri Aurobindo called the yoga of Gita by various terms purna yoga (complete yoga), integral yoga. In his view the yoga of Gita was an integral combination of different paths -jnana, karma, bhakti and self-perfection. The Yoga of the Gita is meant for experiencing, practicing and living it, rather than merely arriving at an intellectual understanding.[10]

As a consequence of this inspiration, Sri Aurobindo has to his credit a very remarkable record as a great scholar and man of letters. He has written voluminously (30) volumes) and on a variety of subjects. The psychological principles in Sri Aurobindo’s writing have served as the inspiration for the renaissance of Indian psychology.

Mahatma Gandhi

While deeply absorbed in public and political life from 1893 to 1948, Mahatma Gandhi had lived with Bhagavad Gita as his primary source of ethical, moral and spiritual inspiration. The Bhagavad Gita was a life-time companion to Gandhi. It was his spiritual reference book. He first read the Bhagavad Gita through its English translation by Edwin Arnold and later on went to reading the Sanskrit original. He subsequently translated the Gita himself into Gujarati under the title of Anasakti Yoga. Gandhi spoke and wrote about the Gita very extensively[11] and his conception of human nature was derived from the Gita. His life was a continuous and constant attempt to live upto the ideal of the Gita.

If one would give an appellation to Gandhi’s interpretation of the Gita it would be Anasakti Yoga-Sthithaprajna. “True individuality is reducing oneself to zero.” -this is the central thesis of interpreting the Gita as Anasakti Yoga. Anasakti is non-attachment. Non attached action is self-action and delinked from the ego. Delinking the ego from action and deliberate refraining from enjoying the fruit of action lead one to reduce oneself to zero or nothingness.

The description of sthithaprajna, a self realised person, in the last 19 verses of the second chapter of the Gita, was very special to Gandhi. As is well known for nearly 60 years until his death, he recited them daily during prayers. These verses contained the quintessence of human nature that Gandhi incorporated in his world view.

Concluding remarks

Indian psychology becomes a living tradition through the Gita and stands on the shoulders of eminent practitioners and scholars leading to a better understanding and handling of human existential crisis and its resolution through better informed existential quest.

[1] Osborne, A & Kulkarni, GV. ( 2016). The Bhagavad GIta. Tiruvannamalai, Sri Ramanasramam.

[2] Yardi, M.R.(2002).Bhagavad Gita. Pune, Bharatiya VIdya Bhavan.

[3] Radhakrishnan( 1958). The Bhagavad Gita.London, George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

[4] Rele, V.G.(1928). Bhagavad Gita- An exposition on the basis of psycho-philosophy & psychoanalysis.Bombay, D B Taraporevala Sons & Co.

[5] Rao, KR & Paranjpe,A.(2017) Psychology in the Indian Tradition. New Delhi, DK Printworld.

[6] Akhilananda, Swami.( 1948). Hindu Psychology-Its meaning for the West.London, Routledge & Kegan Paul Limited.

[7] Gowda, Nagappa K. (2011).The Bhagavad Gita in the Nationalist Discourse. New Delhi, Oxford University Press.

[8] Aurobindo, Sri.(1973) Uttarpara Speech. Pondicherry, Sri Aurobindo Ashram

[9] Minor, Robert.(1991). Sri Aurobindo as a Gita-Yogin in Modern Interpreters of Bhagavad Gira

[10] Nadkarni,MV.(2017)The Bhagavad Gita for the Modern Reader.Oxford, Routledge India

[11] Anand YP.(2009).Mahatma Gandhi’s works and interpretation of the Bhagavad Gita. Delhi, Radha Publications.

Feature Image Credit: istockphoto.com

Conference on Hinduism and Modern Psychology

Watch video presentation of the above paper here:

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.