“There even to this day drops of sandal ointment offered by the gods are seen at Nandi-Kshetra, the permanent residence of Shiva.”[1]

Geography of Nandi-Kshetra

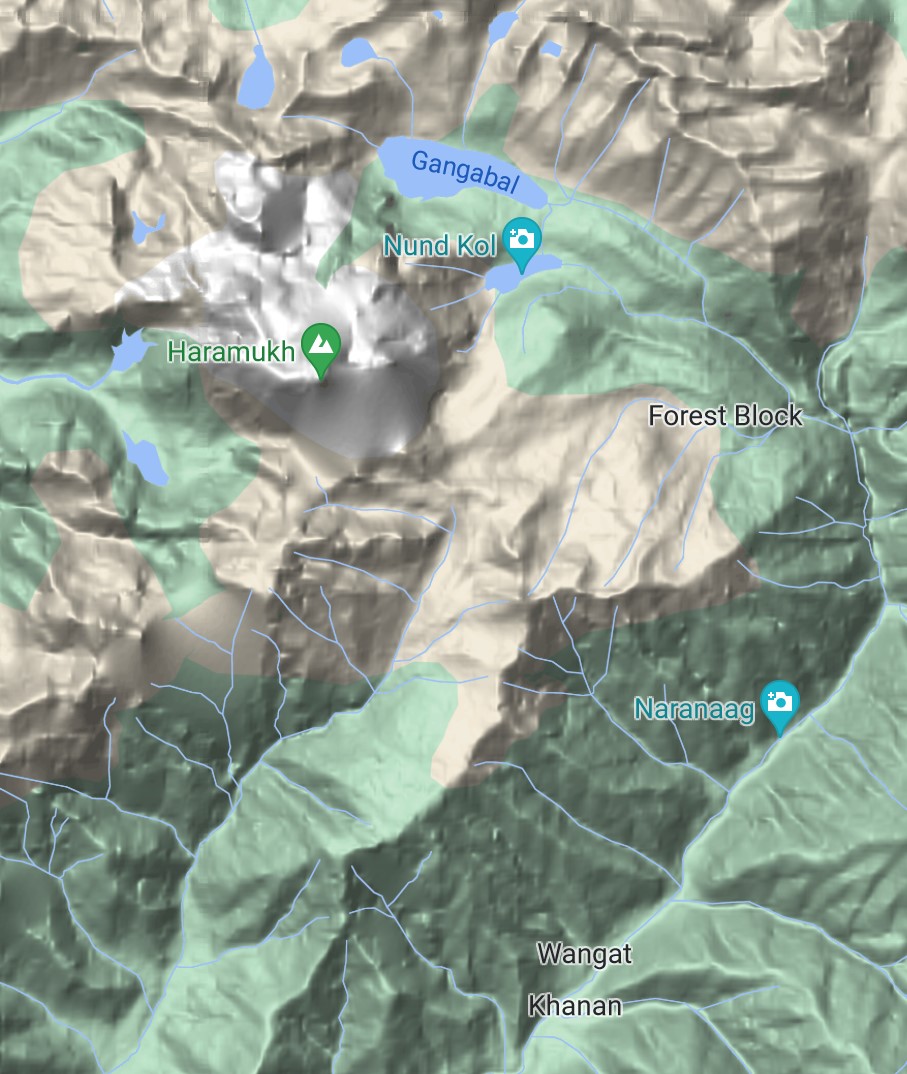

Mount Harmukh or Harmukuta (crown of Shiva) is one of the tallest peaks of Kashmiri Himalayas. The peak measuring 5142 metres lies in the Zanskar range of Himalayas encircling the Kashmir valley in the northeast. Nestled in the north-eastern shadow of the peak, at the base of 3650 metres is the pristine lake of Gangabal. 3.5 kilometres long and half a kilometre wide; it is one of the deepest lakes attaining a depth of 80 metres in the centre. At a short distance south of Gangabal, lies Nund-kol lake of turquoise blue colour, which is named after Nandi, the chief Gana and bull of Lord Shiva. Both the lakes are fed by the glacier melt located on the north-eastern spur of Harmukh mountain.

(Figure 1: Topography of Nandi-Kshetra)

A stream emerges from the Gangabal Lake and is joined by numerous small streams to form Kanakvahini or Wangath river, named after a hamlet located in its gorge. Two miles north of Wangath, lies a group of ruined temples scattered near a spring called Naranag. This is the ancient tirtha of Jyeshtha- Bhutesvara (modern Bhutser), a part of Nandi-Kshetra where numerous Kashmiri kings erected lofty temples in honour of Shiva as Bhutesh-Jyeshtha and donated generously for their upkeep. [2]Thus, the tirtha of Nandi-Kshetra encompasses a landscape stretching from Mount Harmukh to twin lakes of Nund-Kol and Gangabal nestled beneath its environs and the temple complex of Wangath in the east.

Tirthas: The Sacred Centres

After the end of the Mahabharata war, Krishna advised Yudhishthir, the would-be monarch, to learn about Dharma from the highly regarded and wise patriarch of the Kuru family: Bhishma who was lying on the bed of arrows and would attain his death in a few days. The conversation between Bhishma and his great grandson Yudhishthir forms the content of Anushasan Parva, the thirteenth book of Mahabharata. At one point, the discussion turns towards tirthas, and Yudhishthir asks Bhishma to acquaint him with the tirthas of Bharata and explain what qualifies a space as ‘Tirtha’.

“Just as certain parts of the body are more purer than others, so are particular spots on earth that have come to be regarded as sacred; on account of the presence of sacred waters, association with persons that are righteous and through the efficacy of the earth itself[3].”

The elaboration by Bhishma on nature of the Tirthas helps us better appreciate and understand the sacred character of Nandi-Kshetra.

How Nandi-Kshetra became a tirtha?

Story of Nandi-Kshetra is narrated in Nilamata Purana[4], the local Purana of Kashmir which is a goldmine of Kashmiri geography and related legends. The story goes as follows: There lived a Brahmin named Silada in Kashmir who had no son. He performed a severe penance to propitiate Shiva by subsisting on powdered rock for years. Pleased by his penance, Shiva instructed his vahana Nandi to take birth in the human world as Silada’s son. Nandi resisted Shiva’s decision saying that he did not wish to stay away from his lord. Shiva reminded him that he has to do so due to a curse of Sage bhrigu on Nandi. Shiva assured him that after Nandi’s birth on earth, he will stay near Nandi. Consoled by his lord, Nandi took birth as a child and is found amongst rocks by the Silada. He brought the child home and conducted appropriate birth rites. As the child grew older, an astrologer after seeing the hand of the child declared that his life will end soon. Silada began weeping but the child Nandi consoled him and said “Father do not cry. I will obtain a long life by propitiating Lord Shiva.” Saying this, he went to the sacred peak of Mount Harmukh in the Himalayas, near which was a pristine lake of Nund-kol also called Kalodaka (destroyer of sins). Half immersed in the lake and carrying a huge rock on his head, Nandi started his penance. Hundred years went by and in Varanasi, where Shiva was staying, his consort Parvati reminded him of his promise to Nandi. Shiva at once started for Kashmir and went to Kalodaka lake accompanied by all Gods. There he found Nandi, weakened by cold and hunger, stalked by death. Shiva sent the death away and gently reminded Nandi of his former birth. He declared that Nandi shall remain close to Shiva at a spot one yojana east from the lake. There his manifestation as swayambhu linga called Jyeshtha is already present and worshipped by sages daily with water from Gangabal lake. At that spot, sage Vashishtha will erect an image of Shiva and Nandi which shall be worshipped by everyone. Saying so, Shiva took Nandi with him and they climbed the Harmukh peak. As instructed by Lord Shiva, sage Vaishishtha erected the image of Hara and Nandi at a place near Jyeshtha linga. Here, Shiva resides in the form of Bhuteswara or Lord of Ganas of which Nandi is his favourite and chief Gana.

As the name suggests, the Nandi-Kshetra became a tirtha due to the penance of Nandi and manifestation of Shiva on request of his devotee. The incredible tough penance of Nandi by standing in the waters of Nandikund or Nund-kol, rendered its waters pure. Pleased at his austerities, Shiva directed sage Vashishtha, one of the most illustrious sages of Puranas who resided in his hermitage at that place, (today called Wangath) to erect the image of Shiva and Nandi at Bhutesha, where common men, sages and Gods alike worship the image with various offerings. Mount Harmukh is called Kailash of Kashmir where Shiva took up his permanent residence along with his consort Parvati and his Ganas. Thus, by association with Lord Shiva and pious Nandi the entire landscape stretching from Mount Harmukh to Bhutesha in the east became sanctified as Nandi-Kshetra.

Ganga of Kashmir

Another marker for the tirthas as mentioned by Bhishma is presence of sacred waters. There cannot be a tirtha without waters. The word ‘sacred waters’ is used multiple times in the epic to describe a long list of tirthas— rivers, lakes and springs spread across the Indian subcontinent. The belief in the purifying and nourishing powers of water has been a part of the Indian psyche since the earliest Vedic period. The ritual of drinking and bathing in these sacred waters is considered purifying, for they do not just physically cleanse the body, but also symbolically cleanse the soul by washing away sins. No waters in Indian civilization is more symbolic of these powers than river Ganga – the very embodiment of sacredness against which the worth of other tirthas is measured. Bhishma explains the powers of Ganga with a beautiful metaphor; Just as sun when it rises in dawn, blazing in its splendour dispels the gloom of night; similarly a person who has bathed in Ganga shines in splendour being cleansed of all his sins.

In the widely popular tale of descent of Ganga as narrated in Puranas and Mahabharata, Ganga descended on earth at request of King Bhagiratha, the scion of Ikshvaku lineage. He had performed a severe penance to liberate the souls of his sixty thousand uncles who could attain salvation only at touch of Ganga waters. Pleased by his penance, Ganga agreed to come to earth but warned that her turbulent fall would be so great that earth may sink under the weight of her waters. To prevent this from happening, Lord Shiva caught the descending waters in his matted hair locks and released Ganga gently in streams.

The central position that Ganga enjoys in Indian civilization due to its nourishing and purifying properties, led to the phenomena of translocation of Ganga on the regional rivers. Hence, for Hindus residing in places far from Gangetic plains like Kashmir, a regional river was identified with Ganga. River Sindh, 108 kilometres long is the largest tributary of River Jhelum, the lifeline of Kashmir. In Nilamata Purana, river Sindh is considered as an embodiment of Ganga who came to Kashmir at the behest of sage Kashyapa to help her sister Vitasta/Jhelum purify the valley.

Although modern geologists put the source of Sindh at Malachoi glacier near Zoji-la Pass, for ancient Kashmiris, her true source lies at Gangabal lake. I believe that the identification of river Sindh as Ganga and location of its ‘source’ at Gangabal have strong geographical and cultural underpinnings. Located at the foot of Mount Harmukh or Harmukuta which literally translates as ‘crown of Shiva’ and being fed by the melt of its glacier gently rolling down the slopes, evoke the story of descent of Ganga in the minds of visitors. Streams issuing from other surrounding lakes fed by the melt of Harmukh which join to form Wangath river or Kanakvahini river which would later become Sindh as it descends down in Kashmir valley is similar to original Ganga in Uttarakhand where various streams meet at different geographic points to form united Ganga which leaves the mountains at Haridwar.

The lake of Gangabal is referred to as Uttara-manasa or Northern Manasarovar owing to its purity and sacredness. The Manasarovar located in Tibet is one of the most sacred pilgrimage sites of three religions: Hinduism, Buddhism and Tibetan Bon religion. It is said to have been conceived by Lord Brahma in his mind and hence the term – Manas (Mind) + Sarovar (lake) i.e. the mind-born lake.

Pilgrimage – Journey to eternal

In Anushasan Parva of Mahabharata continuing their conversation, Yudhishthir asks Bhishma to explain why one should visit tirthas? What are the merits attached to visiting the sacred waters of earth? Bhishma tells him that the supreme rishis have revealed the knowledge of ritual sacrifices (yagna) and the fruits obtained from their performance in holy Vedas. But a sacrifice requires various materials for performance and wealth for donation, hence can be conducted only by the kings and the wealthy. But even those devoid of wealth and proper means, unmarried or without wife (only a householder can perform sacrifices) can acquire merits equal to, and sometimes greater than one obtained from sacrifices. This is achieved by undertaking pilgrimage to holy tirthas. By bathing in the sacred waters, offering ablutions of sacred water to ancestors (pitris) daily and reciting and listening to the name and stories of tirthas, all bestows merits on performers and washes away the sins and they become eligible to attain heaven when they leave this world.

Bhishma then narrates to him the prominent tirthas located all over the subcontinent and fruits obtained by visiting them. The Nandi-Kshetra of Kashmir finds mention in his elaboration as he says:

“Setting out for Kalolaka (Nandikunda) and Uttara-manasa, and reaching a spot that is hundred yojanas remote from any of them, one becomes cleansed of the sin of foeticide, One who succeeds in obtaining a sight of image of Nandiswara, becomes cleansed of all sins.” Similarly, for Nund-Kol lake, he explains “Having gone to Kaloda, one obtains one’s breath of life again[5]. This is keeping in spirit with the story of Nandi as narrated in Nilamata Purana who had undertaken a penance to escape death and achieved his breath of life again by propitiating Shiva.

The most popular pilgrimage which was undertaken by Kashmiris of the past and has continued till present is the annual pilgrimage to Harmukutaganga or Gangabal lake in the month of Bhadrapada (August-September). The status of Gangabal in Kashmir has been similar to the holy tirtha of Haridwar on the bank of Ganga. Since ancient times, Kashmiris have embarked on this pilgrimage to immerse the ashes of the dead and perform the shraddha ceremony to liberate the souls of the deceased. The pilgrimage has found mention in Rajatarangini of 12th CE and continued through the literature of the colonial period. Walter Lawrence, the British civil servant who had visited the valley during his numerous travels, describes the pilgrimage in his travelogue “The Valley of Kashmir” (1895),

“Ganga Ashtami, the eighth day of the waxing moon of Bhadron is the day when Hindus take the bones (astarak) of their dead to the lake beneath Haramukh and perform the sharadhi service for the departed.”

The pilgrimage stopped in between due to political turmoil and unrest, but was restarted again after 100 years in 2009. Organised by Harmukh Ganga (Gangabal) trust, the 36 kilometres long steep journey starts from Naranag where lies the grand ruins of temple of Bhutesha and ends at Gangabal where yagna and shraddha are performed by the pilgrims.

The grand ruins of Bhutesha- Jyeshtha

Two miles above Wangath, in the gorge carved by Kanakvahini river, lies seventeen ruined temples clustered in two groups. The first description of the site during the colonial period was by Bishop Cowie, 1866 and later the elaborate sketches of existing buildings were recorded by Major H.H Cole under the heading ‘Temples near Wangat’ in his publication ‘Ancient buildings in Kashmir’. However, the identification of the ruined complex with the sacred ancient site of Bhutesha-Jyeshtha was done by renowned historian-archaeologist Marc Aurel Stein who visited the site in 1891 and is also credited to have first translated Kalhana’s Rajatarangini in English.

The two groups of temples are located 200 yards apart and referred as eastern and western groups of temples by Stein. Based on careful study of numerous references of the site in Rajatarangini, Stein identified the western group of temples as Jyeshtha. The group contains one large temple surrounded by small cellas. Nilamata Purana tells of a swayambhu linga (naturally occurring linga; not carved by men) by name of Jyeshtha worshipped by sages from time immemorial with the water brought from Gangabal lake; while the erection of temple complex surrounding the linga was credited to emperor Lalitaditya of Karkota dynasty. The eastern group of temples, comprising a central temple enclosed by a stone wall was identified as Bhutesha. Stein took help of an interesting incident referred to in Rajatarangini in discovering the identity of the shrines.

The great king of Utpala dynasty, King Avantivarman (855-883 AD) ruled the prosperous kingdom of Kashmir and was aided in this task by his efficient and loyal minister Suravarman. One day the king paid a visit to the shrine of Bhutesvara. As he made customary donations of sacrificial apparatus to the temple, he was surprised to see Haak, a bitter tasting leafy vegetable being placed in front of Lord’s image as an offering. He enquired with the priest who narrated their poverty with folded hands “O noble king, in the district of Lahara (drained by Sindh river & its tributaries) resides the powerful Damara (feudal landlord) Dhanva who is very close to your minister Suravarman and is treated like a son by him. That Damara, fearing no one, had taken over all the lands belonging to Bhutesvara. Hence, in absence of any income for maintenance, we are forced to offer God the edible plants growing in the wild.” Avantivarman was in a dilemma. He abruptly returned from the shrine and when Suravarman, who was waiting outside the temple, asked for his sudden departure without completing his prayers, the king did not give a proper reply. However, through his sources, Sura got to know what had happened in the antechamber of the shrine. Angry, he went to the Bhairava shrine located in the vicinity, got it vacated by the people and sent messenger after messenger summoning Dhanva to arrive at Bhutesvara at once. After a few hours, the Damara arrived with his full retinue, arrogant in his demeanour and did not pay proper respect despite knowing that royal forces including the king himself was present at the place. As soon as Dhanva entered the temple of Bhairava, armed men cut off his head in front of the image of Bhairava on signal from Suravaraman. His body was disposed of in a tank nearby. When the king heard what Suravarman had done to Damara whom he loved like his own son, he was impressed at his loyalty. Suravarman then brought the king to the Bhuteshwar temple and made him complete his worship.

In the vicinity of the temple complex there is no other water tank except one at north-eastern corner of eastern group of temples, outside its enclosure wall. Stein describes it as “an oblong tank lined by ancient slabs filled with limpid waters of a spring.” This spring is the ancient Sodara spring, today called as Naranag. 20 yards west of the tank and outside the enclosure stand a small solitary ruined temple which can be ascertained as Bhairava shrine where Dhanva was killed. Since Bhairava is associated with bloody sacrifices, his temples are located some distance from the main temple. The location of the Sodara spring and the Bhairava shrine just outside the walls of eastern group allowed Stein to identify the group with the sacred site of Bhutesha.

Bhutesha-Jyeshtha in History

This place not only lies on the return pilgrimage from Mount Harmukh and adjoining lakes but itself formed an important tirtha frequented by Kashmirians including the kings many of whom were devout Shaiva worshippers. Their donations, activities and stories have been described extensively in the magnum opus history of the region: The Rajatarangini of Kalhana. The earliest history of Kashmir is steeped in legends, myth and local tales prevalent during that time. Many historical figures were cloaked in supernaturalism and magical elements which elevated them to the level of super-humans. One such king of early Kashmir is King Jalauka who is said to be the son of King Ashoka. The text faithfully preserved the memory of Mauryan king Ashoka whose presence in Kashmir is well attested by the historical sources; however his son is more of a legendary figure.

A devout Shaiva, the king had heard the recital of Nandi Purana and made a vow to worship Shiva by visiting the shrine of Jyestha located in Nandi-Kshetra every day. To help in this task, were his friends Nagas who would carry the king on their backs flying through the air. The king would worship the linga with various offerings and water of a fine spring called Sodara located in the premises. He also erected a temple of Jyeshtha Rudra in Srinagar in honour of Shiva, but in absence of Sodara spring it could not compare with the Jyeshtha of Nandi-Kshetra. One day the king was so busy in royal affairs that he became late and had very less time to reach Nandikeshtra on time for his prayers. As he was repenting his mistake, a spring burst forth near the royal palace, the waters having taste and appearance similar to Sodara spring. To test the identity of spring, the king threw a golden cup with a closed lip in the Sodara spring at Nandi-Kshetra and two days later found the same cup floating in the newly formed spring at Srinagar. With Shiva’s blessings, the shrine of Jyeshtha-rudra in Srinagar was complete. Stein identified the Sodara spring in Nandi-Kshetra with the Naranag, an oblong tank lying near the ruins, and the spring which appeared in Srinagar with Sudar-khan, a narrow inlet on the west side of Dal lake which also happens to be the deepest portion of the lake.

Donations and Retirements

The site of Bhutesha-Jyeshtha was frequently visited by the political class of Kashmir who donated generously to the temple. For instance King Narendraditya is credited to have built the stone temple at Bhutesha and offered several flowers made of precious metals and stones along with other treasures. The great Kashmiri conqueror King Lalitaditya of the illustrious Karkota dynasty erected a lofty stone temple of Jyeshtha-rudra and richly endowed it with lands and villages. He also dedicated large sums of treasures won from his expeditions to Bhutesa situated in the vicinity of Jyeshtha. Pious Shaivite King Sandhimati, popularly called Aryaraja abdicated his throne and retired to Bhutesha. He casted off his royal attire and took to simple living as a mendicant, spending the rest of his life in service of Bhutesha Shiva. Not only Kings, Kalhana fondly records the yearly visit of his minister-father Champaka to Nandi-Kshetra, who distributed his wealth generously at the shrine. He introduced the sacred tirtha to the great King Jayasimha of Lohara dynasty, and the latter provided for grand arrangements at Nandi-Kshetra for celebration of the festival of the full moon of Ashadha month. Sumanas, the younger brother of minister Rilhana constructed a Matha at Bhutesha and pleased his ancestors with the offering of sacred waters of Kanakvahini (Sindh) river.

Conclusion

Thus, the landscape of Nandikshetra became a tirtha on account of association with Shiva and his chief Gana Nandi. Mount Harmukh became Kailash of Kashmir; Nund-Kol the sacred lake where Nandi did his penance. At the site of Jyeshtha where already Shiva was worshipped as a naturally occurring linga, the image of Shiva and Nandi was installed by sage Vashishtha. Frequent visits and donations by royalty of Kashmir transformed into a significant tirtha of Kashmir. Adding to the sacredness of the landscape was the presence of Ganga in the form of Kanakavahini/Sindh river which originated from Gangabal lake, at foot of mount Harmukh. The imagery replays the cosmic act of descent of Ganga on earth first in Shiva’s locks who releases the sacred water in gentle streams. The annual pilgrimage to the lake by Kashmiris highlights its importance in Kashmiri culture akin to that of Haridwar for subcontinent Hindus.

Selected Bibliography

- Rajatarangini of Kalhana, translation by M.A Stein

- Nilamata Purana translation by Prof Ved Kumari

- Mahabharata, critical edition translation by Bibek Debroy

- Mahabharata translation by Kishore Mohan Ganguly

- The Valley of Kashmir (1895) by Walter Rooper Lawrence.

- Eck, Diana L. 1981. India’s “Tīrthas”: “Crossings” in sacred geography. History of Religions 20(4): 323-344

[1]Rajatarangini 1.36

[2] Picture – Google Earth

[3]Anushasan Parva chapter 108

[4] Nilamata Purana – 1061-1131

[5]Mahabharata Section 85 – Apad dharma parva

Feature Image Credits: dreamstime.com

Watch video presentation of the above paper here:

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.