(This is the sixth article of the series titled ‘Unknown Tales from the Puranas’. There are myriad stories from puranas and upapuranas that are hardly known to most of us. The series will cover such lesser known tales, as well as unknown versions of the popular tales from pauranika sources. Read the earlier story here. The present story narrates the birth of Skanda/ Guha/ Kartikeya as found in the Kaumārikākhaṇḍa of Skandapurāṇa.)

The most common tale of birth of Kārtikeya involves the prolonged honeymoon of Śiva and Pārvatī, disturbance by Agni in the form of a kapota, Śiva discharging the semen in Agni, which is then discarded by him in the Gaṅgā, which then enters the wombs of six Kṛttikās, who conceive, and fearing the wrath of their husbands discard the six foetuses in the reed forest, which ultimately fuses into a six-headed one. Thus the names Śivaputra, Gāṅgeya, Agnija, Kartikeya, Śarajanmā, Ṣaḍānana, etc.

But Skandapurāṇa offers another additional story, in the Kaumārikākhaṇḍa under Māheśvarakhaṇḍa (29.89ff). The semen discarded by the Gaṅgā becomes the lustrous Śveta Mountain. Agni is then invited to Himalaya, to carry the offerings for God, being offered by the Saptarṣis. There, Agni spots the beautiful wives of the Seven Sages, radiant like the golden kadalistambha, or the soothing rays of the moon.

Agni is enamoured by their divine beauty. However, he quickly realizes the sinfulness of his actions. He also understands that he will incur immense ill-fame. Heart-broken, he retires to a forest, and thinks over ideas to mate with them. Finding no apparent solution, he ultimately becomes unconscious due to excessive lust.

When Svāhā, the wife of Agni, gets to know of this situation, she is delighted. She thinks to herself that Agni has stopped being interested in me, due to our long association; and now desires for new partners in the chaste wives of the Seven Sages. She decides that she shall assume the forms of these ladies, and approach Agni for her satisfaction.

First, she assumes the form of Śivā, wife of Sage Aṅgiras. She approaches Agni, and is successful in copulating with him. She also informs him that the wives of other sages would follow, too. She states that he is their perpetual lover, and their minds are fixed in him.

After being satisfied, she goes to the forest, and assumes the form of Suparṇī, a garūḍī; thinking that if someone spots her in the form of Śivā, a chaste Brāhmaṇa lady would be unnecessarily blamed. In that form she flies to the top of the Śveta Mountain, and deposits the fiery semen of Agni in a golden pot in the Reed forest, as she is unable to bear it any further.

This is repeated with the forms of wives of all other sages, but Arundhatī, the wife of Sage Vasiṣṭha. Svāhā could not assume her form due to the power of her penance as well as her regular services to her husband. So, she deposits Agni’s semen six times in the golden pot.

Agni, after the entire incident, realizes his sin; and resolves to cast off his physical body. A divine voice declares that he need not do so; for, it was ‘inevitable future’ that he resorted to another man’s wife, albeit only mentally. It was actually his own wife. He would therefore receive the punishment of indigestion in the sacrifice of Śvetaketu, due to continuous offerings of ghee. Agni is then said to visit his son so born.

The text then suddenly takes a U-turn, and proceeds to explain why Svāhā could assume the forms of wives of six of the sages. They had, due to their ignorance, bathed in Ganges at the place where Śivas’s semen had been cast off by Agni. They got excited with passion, and deluded by its brilliance. They became bashful of their husbands and decided to hide on the banks of Gaṅgā.

Skandapurāṇa states that Svāhā entered their bodies and took away the refulgence. They were grateful to her for this service, and did not curse her for her assuming their forms to mate with Agni. Their husbands later came to know about their impurity by means of their spiritual knowledge, and abandoned them.

Returning to the original storyline, the text then explains Agni meeting his miraculous single-bodied, but six-headed, twelve-eared, twelve-eyed, twelve-handed, and twelve-legged son, Guha. On the first day, he was a mere lump of flesh. On second day, he had the form of an individual; on third, he became an infant; on fourth, he became a fully grown man, and was consecrated on the fifth day. Agni gave him his Śakti missile, and blessed him for the upcoming war.

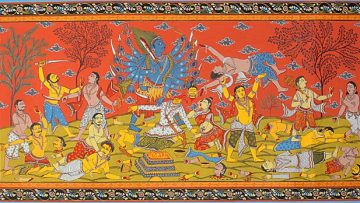

Soon, due to his activities killing thousands of Rākṣasas protecting the Śveta Mountain, the army of gods attacked him as per the order by Indra. Guha with flames of fire discharging from his mouth, burnt them down. Ultimately Indra hurled his thunderbolt at him multiple times.

From the wounds of the thunderbolt are born Śakha and Naigameya, who resembled Skanda in their appearance and power. Indra ultimately accepted defeat and sought refuge in Skanda, receiving his blessings. From Skanda were also born eight Śiśumātaraḥ, and a son Lohitākṣa is born from his blessings.

Later everyone associated with the birth of Skanda, i.e., Śiva, Pārvatī, Agni, the six wives of sages, Svāhā, and Gaṅgā, gathered to claim him as their son. He then accepted to be a son to all of them, and granted them boons. The six wives of sages were converted into six stars of the Kṛttikā constellation. Svaha became favourite wife of Agni, and offerings of Havya and Kavya are offered in fire with her name. Agni got shares in all sacrifices, as well as sons.

The most significant observation that can be made from the story is about the ideas of chastity of woman, and her reverence and dedication to her husband. This is evident from the plotting by Svāhā as well. She chooses to assume forms of ‘other women’ her husband fancies, over looking for other partners instead. The abandonment of wives by the six sages is also obvious in this context.

The story becomes a star myth, once the creation of Kṛttikā constellation along with Abhijit is incorporated. Svāhā’s reverence for Brāhmaṇa women also highlights the well-recognized approach of respect towards the community. The parts noting the development of Skanda from a ball of flesh to a fully grown human hints at good knowledge about embryology and growth of foetus; though the durations mentioned are obviously fantastic.

Agni’s sin of mating with the wives of sages, though only mentally for the reader, is actually physical, too; if we look at it from his own perspective. The treatment given to his mahāpātaka is very mellow. It is simply dismissed as ‘inevitable future’, probably to avoid the deity becoming mahāpātakī.

The U-turn in the narration also hints at the portion being a later addition/ interpolation; as it does not go in flow. The sudden eulogy of Skanda by Sage Viśvāmitra, complete with a phalaśruti also highlights the same.

Overall, it is fascinating to see how purāṇas use various ideas to navigate a narration, like rūpa-parivartana (assuming different forms), motifs of śāpa, pratiśāpa, uśśāpa, and vara, i.e., curses, counter-curses, antidotes to curses, and boons, and not-to-be-missed tadka of fantasy.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.