From this week onwards, we will traverse through the beautiful world of Indian Textile Motifs and their significance through the gaze of Shefali Vaidya. This week we will talk about the exquisite Nava Nari Kunjara motif, a composite animal figure of an elephant that is composed by nine women that depicts not only the artist’s skill but also its deep spiritual context.

Hindu view of art states that our minds perceive everything through our senses. This perception is called Rasanubhuti. In both Vedic and Puranic literature, there are mentions of this power of sense-perception that invokes a particular feeling within us, the Rasa-Bhava. The main aim of all forms of art as per Hindu theory of aesthetics is that the art object has to invoke the desired rasa in both the creator of the art as well as the Rasika, the consumer. All art is therefore, deeply symbolic and every motif stands for a greater spiritual principle. Nothing explains this better than the Nava Nari Kunjara motif, a unique motif seen in Indian art.

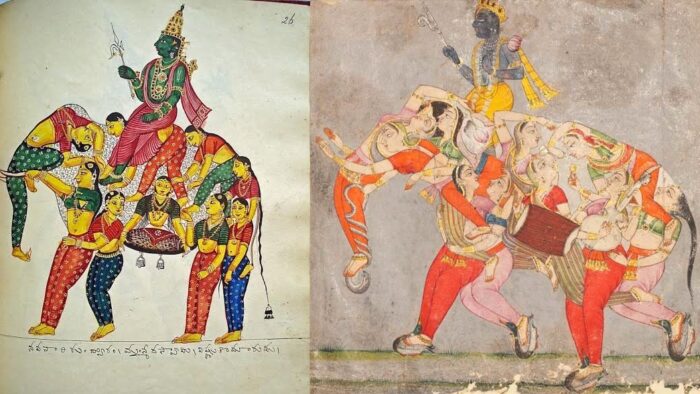

Last year, on my trip to the Nava Thirupathi temples of Tamil Nadu, I discovered an intriguing motif on the walls of the Gopuram of the Sri Adinatha Swamy temple of Azhwar Thirunagari in Toothukudi district of Tamil Nadu. It was the motif known as Nava Nari Kunjara, a composite animal figure of an elephant that is composed by nine women.

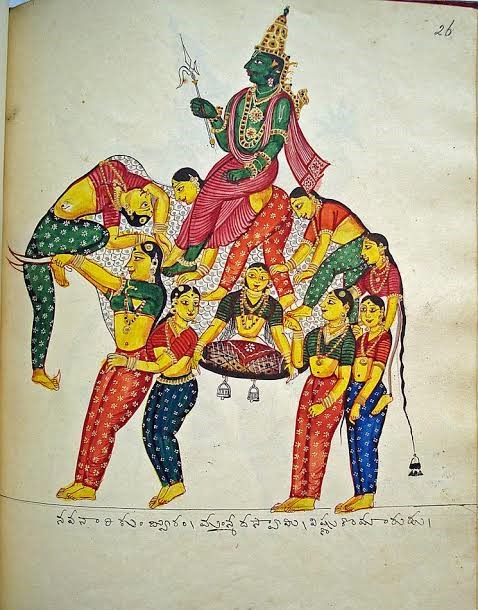

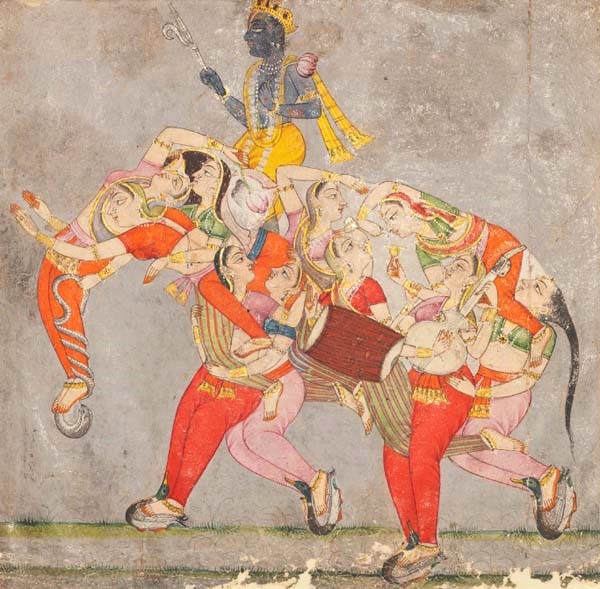

The same motif is also seen at the temple of Shri Vishnu at Thirukurungudi near Thirunelveli. The Nava Naari Kunjara is n unique motif in Indian art, where an elephant is depicted as being made up of nine women. The women represent the nine Rasas as described in the theory of Hindu Aesthetics. The elephant that is composed of these female figures is symbolic of strength as well as of control over sense organs. Shri Krishna is often depicted as riding this elephant as Shri Krishna is described as the Rasaraj, the master of all nine Rasas.

The NavaRasas are the nine essences that define expression of emotions in all Indian Art Forms – visual, literary as well as performing! The nine Rasas are as follows; Shringara or erotic love, Hasya or the comic element, Karuna or pathos, Veera or heroic, Bhayanaka or terrible, Bibhatsa or Odious, Adbhoota or strange and Shanta or calm.

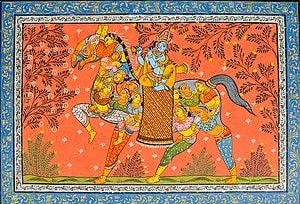

This motif of Nava Nari Kunjara is found quite frequently in the Pattachitra paintings of both Odisha and West Bengal. It is also found in the sculpture of the 10th-century terracotta temples of Bishnupur, West Bengal as well as in the granite temple sculptures of Tamil Nadu in Vaishnava temples. Often, the elephant is shown with Shri Krishna on his back, but sometimes, it is possible to find a standalone figure of just an elephant composed of nine female figures, with no rider. Sometimes, the Hindu God of Love, Kamadeva is also depicted as riding the Nava Nari Kunjara. In the maharangamantapa of the Virupaksha temple in Hampi, Karnataka, Kamadeva and his consort Rati are depicted as riding panchanari turaga (horse composed of five women) as well as anava nari kunjara.

The motif is remarkable in its meaning as well as in the complex visual depiction. Interestingly, this predominantly Vaishnava motif as seen in India also finds depiction on the wall murals on the Buddha temples of Sri Lanka. Only, in the Sri Lankan version, the nine women are replaced by nine male monks, considering the fact that Buddhism prized austerity and asceticism over desire or Kama.

During the Mughal rule, this motif was copied by court artists in Mughal miniature paintings, where it was stripped off of all its ritual meaning, and was reduced to being a symbol of the Sultan’s virility. There are several depictions in Mughal miniatures paintings of the sultan riding an elephant composed of nine women. There are depictions of camels as well in a similar fashion.

Not only that, this motif became so popular in Islamic Sultanates as a symbol of royal power and virility that it was enacted in real life by trained female acrobats, as personally witnessed by Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, a 17th-century French traveler to India during his visit to the kingdom of Golconda.

He describes the spectacle of the Nava Nari Kunjara motif being enacted by real live women in the following words in his book, Travels in India. “These women have so much suppleness and are so agile that when the King who reigns at present wished to visit Masulipatam, nine of them very cleverly represented the form of an elephant, four making the four feet, four others the body, and one the trunk, and the King, mounted above on a kind of throne, in that way made his entry into the town.”

This is a classic example of stripping a sacred religious motif of all its spiritual symbolism and turning it into a secular symbol of royal pomp and power. However, in Hindu symbology, the motif of the Nava Nari Kunjara continued to be held sacred. Even today, you see the motif being painted often in the Pattachitra paintings of Odisha.

Later on, we also see variations of this motif as Sapta Naari Kesari – a lion composed of seven women, Nava Naari vrishabha – a bull composed of nine women or even Nava Naari Turaga or Ashwa or a horse composed of nine women. In some depictions inspired by the Nava Nari Kunjar, the animal is depicted as being composed of a medley of various other animals.

The Nava Nari Kunjara motif has also been adapted by India’s weavers in many places. In Patan Patolas, it is interpreted slightly differently as nine alternating motifs of female figures and elephants. In Sambalpuri Ikat, they still follow the original aesthetic and depict the Nava Nari Kunjara in its original form. The creativity of the weaver lies in the acrobatic postures of the figures and their placement to make the elephant figure.

The composition of the Nava Nari Kunjara follows a set convention of nine beautiful women dressed in all their finery placed creatively to form an elephant figure. Four of the female figures form the elephant’s legs. The long plaited hair of one of the women is usually depicted as the elephant’s tail. The figure of a single woman serves as the face of the elephant with her graceful feet extended as the trunk. The hands of another female figure are extended as the tusks. Sometimes, the hands are shown carrying whisks or fans to form the ears. The remaining two female figures form the back and the belly of the elephant.

The deity riding the elephant is often depicted carrying an ankusha or an implement to goad and control the elephant. If Kamadeva is depicted riding the Nava Nari Kunjara, he is seen with his sugarcane bow.

The Nava Nari Kunjara is an extremely beautiful, complex motif in Indian art that highlights not only the artist’s skill of composition and placement, but also has a deep spiritual context that places the motif within the realm of Hindu spiritual thought and aesthetics.

References

- Jean Paul Tavernier, Travels In India (1676)

- Shyamalkanti Chakravarti, कलामेंनवनारीकुञ्जरक्रीड़ा

- (Kala Me Nava Naari Kunjar Kreeda)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.