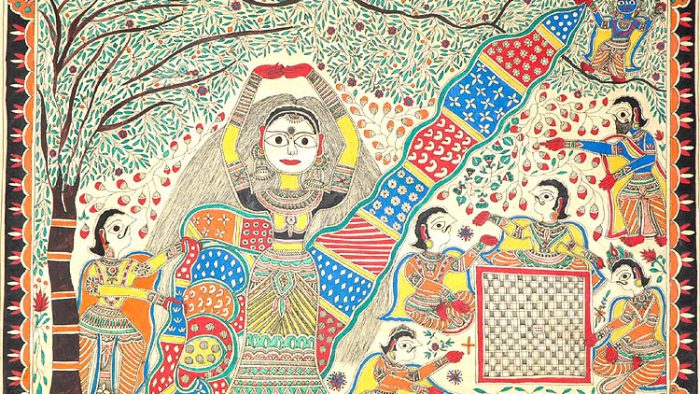

The Disrobing of Draupadi in the great sabha of the Kurus has haunted generations in India for centuries. As it is well known, this clearly increased the entropy of adharma making a formal war between the Pandavas and Kauravas almost inevitable. Vidura was the first to foretell the impending tragedy in unequivocal terms, apart from the all-knowing Sage Veda Vyasa and Lord Krishna.

All the elders of Kuru dynasty knew it clearly, that a great tragedy was imminent; if not immediately, then gradually. The great sages, scholars, and common people of India have wondered and dwelled upon this episode, and the subsequent tragedy – as a matter of fundamental importance to mankind in general and our civilization in particular.

What makes this tragedy unfathomable, enigmatic, and indigestible is that the episode takes place under the observant eyes of the venerable Bhishma, the great guru Dronacharya, the wisest Vidura, the devout Krupacharya and the King Dhritarashtra himself.

What is worse is that this happens under the watchful eyes of Draupadi’s husbands – the great Pandavas, and own her doting mother-in-law Kunti. The best of wisdom that was available in the Kuru Kingdom was present for action, and yet something that they would all be ashamed of for the rest of their lives, happened.

The notable absentees in sabha were Vyasa Maharshi and The Great Lord Krishna himself. We have never gotten over this episode that haunts us forever; and we constantly go back to it- just as we look at a wound, to check if that has healed itself or not. That wound shall never heal – for it is meant as a warning for all future generations.

Some fundamental questions about the incidence-

1) How is it that a dharmic tradition let this happen?

2) How can a set of exponents of dharmic path and revered for their dharmic orientations turn a Nelson’s eye to such a dastardly act that could bring down a civilization?

3) Worse, how can they continue to be revered either as heroes or as exponents of dharma?

In this discussion let us leave Dhritarashtra, Duryodhana, and Dushyasana aside. Dhritarashtra was blind in his love for his son, and the other two were evidently and acknowledgedly evil. Duryodhana clearly says “I know what dharma is, but that is not in my nature, I know what adharma is, but I cannot retire from that”.

Fundamentally, we hold Bhishma, Dronacharya, Kripacharya, Vidura, and the Pandavas themselves responsible for their inaction and the subsequent tragedy. For if they could not, nobody else would have been able to.

Bhishma

In this episode, the greatest disappointment is Bhishma. Let us explore his essentials. He had taken a great vow that he will be a brahmachari forever and never become the king, in order to make way for his father’s second marriage to a younger bride.

He has worked hard to bring up his brothers, his brother’s sons and then his brother’s grandsons. His great sacrifice, ascetic life style is celebrated in Mahabharata. Further, he is the great disciple of Parashurama, the greatest warrior of his time, and an exponent of all shastras and dharma.

He was revered by the sages, feared by the Kshatriyas and was awe-inspiring for the entire masses for the way he led his life and conducted himself. How could he go wrong?

This is where Mahabharata is delivering a key message to mankind. The Indian Scholarly Tradition does not consider his great vow as an act as complementary to dharma. He took this vow to satisfy his own ego and his father’s fascination – neither of them inherently dharmic.

The act had no good of the state and society in mind – which is the principle responsibility of a King. It was to their luck that Satyavati was a great lady, and turned out to be a worthy Queen.

Further, the state was deprived of the best possible King and to that extent, it contributed to adharma. When Satyavati’s sons died and the Kingdom required a King- he should have broken the vow. The Vow itself was not more important than the needs of the Kingdom – that was dharma. Instead he went the exceptional Niyoga way. Once again, the Kingdom lost the opportunity to be served by a great King.

Further, when he contributed to the tragedy of Amba – he should have accepted her request to marry her. That would have been dharma. But yet again he took shelter under his egoistic, and in itself a useless vow. Yet again he failed his in his dharma. He let his personal dharma overshadow the Universal dharma.

In any conflict between the personal and the Universal dharma, the ability to estimate which is greater good and lesser evil is a critical capability and at his most crucial juncture Bhishma – The Great failed. Clearly, in this case, global dharma should have taken precedence but a deep ego within – in the form of attachment with his vow – came in the way of seeing this clearly.

The tragedy continued. When Dhritarashtra was made King, and his willful pursuing of adharma became evident, Bhishma should have expressed himself very clearly. He could have distanced himself even if could not oppose formally (as per his own strict code of conduct).

However, he thought that his vow to protect the simhasana of Hastinapur was more important than stopping Dhritarashtra and Duryodhana treading an adharmic path. Once again the personal dharma took precedence over the universal dharma succumbing to the games that ego plays.

The grand finale of that tragedy – the seeds of which were sown by Bhishma’s own egoistic acts – was the Disrobing of Draupadi. While a great adharmic act (inhuman and beyond) was playing itself – Bhishma was busy calculating whether he had the right to intervene or not. In the end it was left to The Great Lord Krishna to intervene. He intervened without a hesitation, and saved the day for the entire clan- for he alone possessed the clarity for action. Theoretical clarity is much different from the clarity to act.

Tradition views that Bhishma failed in his dharmic journey. Tradition does not approve of Bhishma’s silence. However, it was not a criminal silence. It was a silence that was a result of ego creating confusion, and that is the metaphor for all of us.

It is also a metaphor for how great scholars can lose perspective, particularly those who are stickler for rules. Bhishma was a great stickler for rules, but he lost sight of the principle at a crucial juncture. He had entangled himself with a huge set of rules – all dharmic in their own context – and collapsed under the weight of those rules. When the context required a universal dharmic rule to be invoked he could not shift the context in his mind.

We can wonder that should even disrobing of a lady not bring enough clarity to act, rather than struggle with rules. We have to remember that Mahabharata is a mahakavya – a great poetry – and is full of metaphors. It may have happened in exact somewhere, but that is not the point. It may indeed have. But the striking metaphors are used to communicate a point effectively; that warns mankind, of tragedies that can befall us, if we lose clarity.

The point is also, that we may tend to lose the perspective- even when such a ghastly act is happening- if we overload ourselves with a set of contextual rules, and lose focus on the fundamental principles of dharma. And the main point here is that, this can happen to the greatest of great, such as Bhishma- so the lesser mortals like us, should be greatly cautious.

We somehow open our eyes only after a tragedy has played itself out in totality; just as the Kuru Sabha let Duryudhana, Shakuni, Karna and Dushyanasa disrobe Draupadi. While we express our anguish against Bhishma and other stalwarts we must look inwards and empathize with them hoping that we gain the clarity of action. Let Bhishma’s great fall serve as an everyday reminder to mankind.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.