Asuras: Their Characteristics and Tendencies

Now we come the question of who are the asuras? What role do they play in the Hindu traditions? As mentioned in the first part of the article, this is a huge research area that covers multiple domains within the Indian traditions, from dharma to jnana to the purusharthas. It is best to think of this article as an overview on the topic of asuras, that gives the reader an introduction to the issues at stake.

The modern English educated Indian tends to translate asuras as demons. Even though, most Indians don’t understand what ‘demon’ means in Christian theology, the concept of demon is inextricably connected to other theological concepts such as evil and unholy, and those concepts also get smuggled into our daily language use when we use the term demon. We tend to think of asuras as the villains while the devas are supposed to be the forces of good. However, the notion of asuras as the ‘’bad guys’’ runs into problems. Prahlada, Bali, and Vritirasura were all great bhaktas of Vishnu even though they are asuras. At the same time, many of the stories in the puranas and itihasas revolve around a revered deity such as Vishnu (or one of his avatars), Shiva, and Durga fighting against and killing asuras.

This story from the Chandogya Upanishad encapsulates the fundamental nature of asuras:

In the story, Prajapathi claims that he who has found the ‘Self’ (atman) and understands it obtains all worlds and all desires. The devas and the asuras both heard these words, and said: ‘Well, let us search for that Self’. Indra from the devas, and Virochana from the asuras, approached Prajapathi.

He makes them dress up and gaze into a pan of water and describe themselves. Indra and Virochana both described their physical appearance as they saw it, both well adorned, with their best clothes. Prajapathi said: “That is the Self, this is the immortal, the fearless, this is the Brahman’’. Virochana goes away satisfied. Prajapathi reflects on his absence of critical thought.

Virochana goes to the asuras and tells them that the self (the body) alone is to be revered and served, and that he who reveres and serves the self, gains both worlds, this and the next.”[1]

Thus, the Chandogya Upanishad presents asuras as those who, out of their ignorance, see the body-mind complex as the self, and pursue artha and kama as the highest goals (serving the body).

This article focuses on the role of asuras in the puranas, primarily relying on the Bhagavata and Vishnu Purana. Before delving into the nature of asuras, I will briefly discuss what puranas are, the function they serve in Indian culture. It is best to think of puranas as akin to scientific models. Whereas, a particular scientific theory of some phenomena may be too complex for the layman to understand, scientific models are simplified physical, conceptual or mathematical representations and explanations of phenomena that a theory is unable to provide. For example, the atomic model, or the solar system model. Within the Indian traditions, Jnana Marga is the attainment of enlightenment or ananda through the path of knowledge. It involves serious scientific investigation into the nature of human experience. Our acharayas did exactly such an investigation through reflecting on various aspects of human experience from kama (desire) to dukkha (sorrow). Their insights were written down in texts like the Vedas and Upanishads. These are the Indian or Hindu equivalents of quantum physics textbooks. However, not everyone can read and understand quantum physics. Thus, the puranas and the characters within them serve as models that convey the knowledge contained in the Vedas and Upanishads in a simplified form, so that the ordinary, everyday human being can understand them. The most complex philosophical concepts become part of daily life through these stories.

(City of Nine Gates – Pic Credit: ISCKON 2015)

A great exemplar of this process is the story of the king Puranjana and the city with nine gates in the Bhagavata Purana. Puranjana is the representation of the jiva. The city is the human body. The nine gates are the organs of the human body through which the jiva enjoys the sensual pleasures of prakriti. The queen of the city, the young damsel Puranjani is the buddhi which creates the notion of I-hood and mine-ness, the root of ignorance. Thus, the story, as well as objects within the story, serves as models that illustrate and explain complex experiential concepts such as buddhi, jiva, and ajnana.

In both the Bhagavata and Vishnu Purana, the asuras are shown as beings in which two out of the three trigunas, tamas and rajas, predominate over the sattva guna. According to the Bhagavad Gita, qualities, words and actions that promote dharma and jnana are sattvic. These include qualities such as gentleness, peace of mind, and actions such as adherence to one’s sampradayas and reverence towards one’s ancestors and devatas. Sattvic actions are those actions performed without attachment to any goal or desire, detached activity. Rajas is characterized by action arising from desire, while tamas is born out of ignorance and hence characterized as darkness. Tamas is characterized by the quality of inertness as well as actions done without thought or regard to consequences.

It is important to note that tamas and rajas are not necessarily bad qualities. After all, sleep is characterized by the tamas quality of inertia. The universe was in a state of tamas/inertness, before Brahma through his creative activities introduced rajas. And moreover it is through ignorance that one comes to knowledge. The Pavamana mantra introduced in the Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad, has the verse ‘Tamasoma jyotirgamaya’. Ignorance is a necessary prerequisite for knowledge. In the same vein, most human beings in the world are moved by desire. Without desire induced activity (rajas), the world would not function.

The puranas identify asuras as creatures with a tendency to have an excess of tamas and rajas. When tamas and rajas become excessive, they become obstructions to dharma and create adharma. As a result, the asuras become a source of adharma in the world. But what is adharma? If the concept of adharma is the equivalent of, or similar to the concept of evil, then asuras become the Indian equivalent of demons. In order to understand the concept of adharma, we have to understand dharma.

What is Dharma?

Dharma is preoccupied with the altogether social nature of human life, for the qualities of persons, the kinds of person they are and the knowledge and attitudes they have are exhibited in human interactions and relationships. Within Indian culture, associated, interpersonal living and relationships are taken for granted as uncontested fact. Every person lives and every event takes place within some or other social and cultural context.

Within those social and cultural contexts, each of us has a role to play; as a mother, sister, teacher, friend. I am the totality of the roles I live in relation to specific others, cognizant of the fact that the relations in which I stand to some people affect directly the relations in which I stand with others. In the Indian traditions, an action is judged to be good or bad based on whether or not it is appropriate to the context and role of the person performing the action. An action by itself is meaningless. It is the context of the situation that lends meaning to an action, makes it either right or wrong.

In Indian or Hindu ethics, there is no action that is universally right or wrong, independent of the person performing the action, and the context in which the action is being performed. The contrast with Christian ethics is striking. The foundation of Christian ethics is the Biblical God. As the sovereign of the universe, his word is law. And his laws are universally applicable to all human beings at all times regardless of the context. Any action that violates his laws is sinful and evil.

Unlike Christian ethics, which revolves around the doctrines and laws revealed by a divine authority, dharma is entirely about practical life. How do we as human beings, embedded in various roles and relationships, go about in those roles and relationships in the most appropriate way, that results in a harmonious and peaceful society. Indians experience dharma as something that sustains the social order, without which society would collapse.

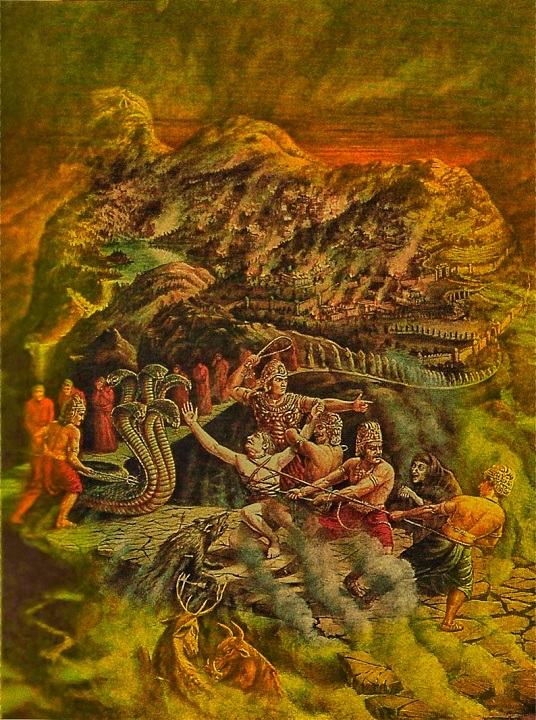

(Vishnu supporting the order of dharma against an asura – Pic Credit: wikimedia commons)

Asuras and Adharma

The first Daityas[2] were born because of paapa and ajnana. Paapa is best translated as inappropriate action and ajnana as ignorance. Jaya and Vijaya, the attendants of Vishnu in Vaikuntha (the abode of Vishnu) were cursed by some rishis to be born as asuras in the world. When the great rishis, headed by Sanaka, arrived in Vaikuntha and wished to see Vishnu, Jaya and Vijaya prevented them from doing so, because they thought these rishis were children because of their physical appearance. This angered the rishis because they perceived ignorance in the behaviour of the attendants. These rishis had transcended the feelings of ‘mine’, ‘ours’ and ‘theirs’. They no longer identified their sense of ‘I’ or self (atman, brahman) with their body. Vaikuntha was supposed to be the abode of those that had attained enlightenment or moksha, and didn’t observe distinctions that arise from falsely identifying the self with the body. By preventing these rishis from entering, Jaya and Vijaya had shown their ignorance. Thus, they were cursed by the rishis to fall from Vaikuntha and be born in the world as asuras.

The birth of the asuras within the womb of Diti was itself caused by a paapa. Diti was not patient enough to wait for the right muhurta to have sexual intercourse with Kashyap. Thus were born the two daityas Hiranyaksha and Hiranyakashipu. These asuras are described as obsessively pursuing power and wealth. They engaged in rigorous tapas in order to obtain that power. The asuras began harassing and killing jnanis and acharyas, and drove the devas out of their abodes in order to establish themselves there. Thus, in their pursuit of the purusharthas[3] kama (desire) and artha (wealth, status), these daityas create adharma in the world. This is a pattern one observes with many of the asuras in the puranas and itihasas. An aggressive pursuit of wealth and power that shows the dominance of the rajasguna. At the same time, the asuras, out of their ignorance, are immersed in the enjoyment of the senses and are not interested in the pursuit of self-knowledge and ananda, which shows the dominance of the tamas guna as well. As mentioned, an excess of both these gunas within asuras causes them to become disruptors of the social order built on the foundation of dharma. In other words, they become a cause of adharma. Hence, the rise of asuras to power, and their reign is often described in the puranas as being accompanied by the sacrificial fires dying out, the ceasing of the Vedas being recited, and the devas being driven out of devaloka. When this happens, a devata, usually Vishnu or Shiva, has to defeat/kill the asuras in question in order to restore dharma.

(Narasimha)

Conclusion: Adharma is not Evil, Asuras are not Demons

One may be tempted to draw parallels between the fall of Jaya and Vijaya from Vaikuntha to the fall of Satan and his minion angels from heaven. However, other than a superficial similarity involving a fall from an exalted status, there is nothing in common between the two accounts or the characters involved in them. Satan and his angel allies were cast out because they sinned by rebelling against the rule of God.

In the case of Jaya and Vijaya, they are cursed to be born in this world because of their ignorance. Their ignorance results in the attendants of Vishnu committing paapa by denying entry to the rishis. Moreover, in Christian eschatology, demons are enemies of God and his creation from their fall to the end of time. There are no ‘good’ demons that are exceptions to this role, and Satan can never reconcile with God. Satan and his minions are evil by nature. Jaya and Vijaya on the other hand, are born as asuras so that they may once again reach Vaikuntha. In the Bhagavata Purana, Vishnu describes the intense hatred that Hiranyaksha and Hiranyakashipu have towards him as a form of sadhana or yoga that will help them attain moksha. It is unimaginable within Christian theology to describe the hatred that Satan has towards God and his creation as something that will help him attain the kingdom of heaven once again.

The fundamental difference between asuras and demons lies in the idea that adharma is not the equivalent of evil. As discussed in the first part of the article, any action that violates God’s laws and commandments is sinful, and anything that opposes and attempts to obstruct God’s will is evil. Without the Biblical God, the concepts of sin and evil become meaningless. Paapa cannot mean sin, because there is no Biblical God in the Hindu traditions to sin against. The same considerations apply to the concept of adharma. And finally, while asuras have the tendency to engage in adharma, not all asuras do so. One of the greatest bhaktas of Vishnu is Prahalada, an asura. Vishnu himself describes Vritirasura as one of his great devotees. The asura king Bali was another devotee of Vishnu who is revered by many Hindus. In some parts of India, Diwali is celebrated by welcoming Bali into one’s home.

If there is one parallel that can be drawn between asuras and demons, perhaps it is that each of them are disruptive to a specific kind or order. Christians experience order as the will of God. God’s will governs the physical regularities and structures we see in the world, such as gravitation, evaporation and the chemical composition of water. At the same time, God’s laws and doctrines are the fountainhead of moral order. The devil and his minions are opponents of God’s order since they are responsible for both natural and moral evil. They cause pain through natural phenomena such as droughts and earthquake and also tempt mankind into sin.

Indian culture experiences order in the following manner. Every creature has a place and a role/s to play. A human being is seen as the sum of the various roles he or she occupies in society. Moral order is experienced as human beings performing actions and adhering to practices that are context-appropriate and fulfilling the various roles they occupy. In the puranas and itihasas, the asuras (with some exceptions) are shown engaging in activities and behaviour that disrupt and threaten this moral order.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BALAGANGADHARA, S. N. Reconceptualizing India studies. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2012.

BOYD, Gregory A. Satan and the problem of evil: constructing a trinitarian warfare theodicy. Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press, 2001.

ROSEMONT, Henry a Roger T. AMES. Confucian role ethics: A moral vision for the 21st century?. Göttingen: V&R unipress, 2016. Global East Asia volume 5.

RUSSELL, Jeffrey Burton. The Prince of darkness: radical evil and the power of good in history. Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press, 1988.

SHASTRI, J.L. Bhagavata Purana. Fourth. edition. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1999.

WILSON, Horace Haymen. The Vishnu Purana. Madras: Christian Literature Society, 1895.

[1]https://www.hipkapi.com/2011/02/28/india-and-her-traditions-a-reply-to-jeffrey-kripal-s-n-balagangadhara/

[2] Asuras are descendants of the offspring of the sage Kashyap and his two wives, Diti and Danu. The asuras who were the children of Diti were known as Daityas, while those who were the children of Danu were known as Danavas.

[3] In the Indian traditions, purusharthas are the four ultimate goals of human life

Feature Image Credit: istockphoto.com

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.