Sister Nivedita and Indian Art: An Introduction

In the preface of Sister Nivedita’s first biography, titled The Dedicated, we read that she spent only a few years in India, though her guru, Swami Vivekananda, gave her unlimited insight into the country and its people. She embraced an austere discipline that enabled her to use this insight and leave its mark in various fields—religion, pedagogy, science, art, politics, and society. Besides, she had intimate friendships with all the leaders of India from 1895 to 1914, who made the era famous. To these, we may add that her intimacy with personalities of lasting fame went far beyond India—for such men who knew and admired her in Europe and America were not a few.

We are presenting here a Story of how Sister Nivedita took it upon herself to inspire and guide the predominantly West-centric Indian artists on their true path without sacrificing focus on either the country’s noble heritage or the visions of modernity. In her quest, she had the support of great friends and like-minded personalities of timeless renown—their words of admiration for Nivedita left traces of her brilliant and pathbreaking mind on the trail of a noble ambition.

It was no exaggeration when Rabindranath Tagore wrote this in the Introduction of Nivedita’s Web of Indian Life: “… Because she had a comprehensive mind and extraordinary insight of love, she could see the creative ideals at work behind our social forms and discover our soul that has living connection with its past and is marching towards its fulfilment. … Sister Nivedita has uttered the vital truths about Indian life.”

An Almost Unread Story

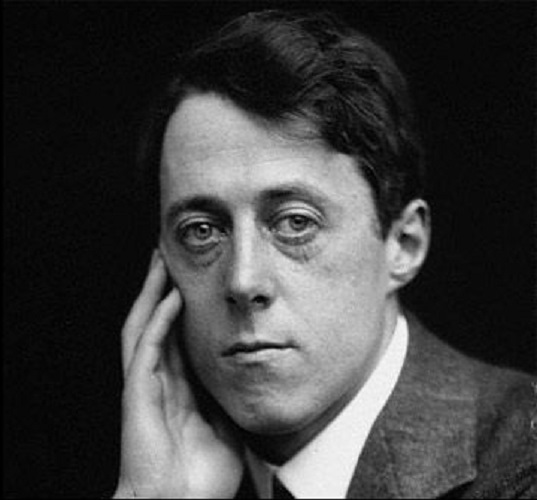

In some recent books on Indian art, the name of Sister Nivedita mostly appears while dealing with the replication of Ajanta frescoes in the early twentieth century. In a few of them, comments are also made about how she linked the revival of Indian art with nationalistic movements. But at best, those citations are more or less fleeting with no worthy attention to the depth of her involvement with or contributions to the Indian art movement. If we delve a little deeper to find out that, we would also gain a comprehensive picture of how a few people tried to reverse colonial chauvinism in the early part of the last century to earn denied recognition to Indian art. The quest for the story begins with an English lady—Christiana J Herringham (1852-1929) and her first visit to India.

(Figure 1: Credit: Exploring Surrey’s Past – Christiana Herringham)

In a book akin to a biography, Mary Lago writes about how the Herringham couple first arrived in India, “In November 1906 Wilmot and Christiana set out as tourists to see India for themselves. At first, her interest in India was general and romantic. ‘You know it has been a dream of many years with me to see the middle of Asia, and all those old cities,’ she wrote to [William] Rothenstein. ‘I should really like to be away a year—and see much more than is possible in one winter.”’

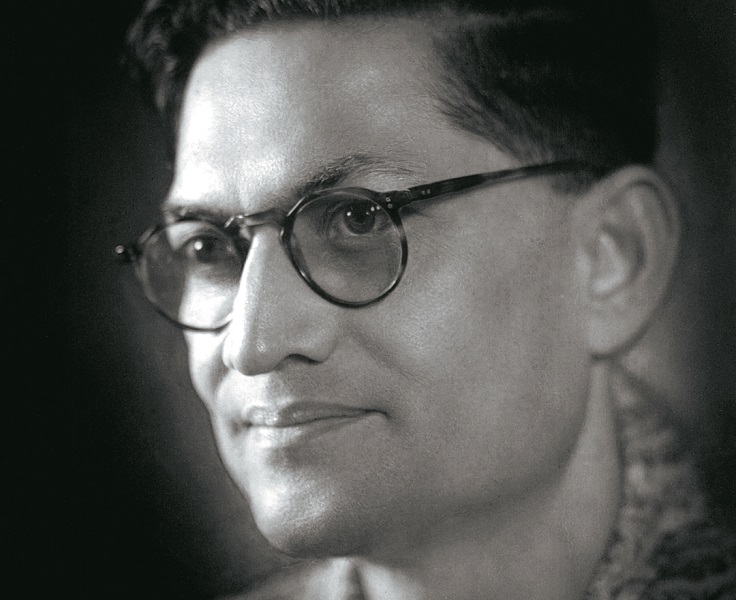

Interestingly, Robert Laurence Binyon (1869-1943) had changed the mere family trip into something more significant. Binyon was an English poet, dramatist, and art historian—known for his study in Far Eastern painting in Europe. In 1893, he began working at the British Museum in London, where he later became responsible for Oriental prints and drawings. Binyon’s first book on Oriental art, Painting in the Far East, was published in 1908 and is still considered a classic. At this time, according to Mary Lago, Binyon was working on his Painting in the Far East, and he requested Mrs Herringham that if they would ever be near the Ajanta Caves, they ‘could bring back some report of the quality and condition of the Ajanta frescoes.’”

(Figure 2: Credit: Naval Historical Society of Australia – Laurence Binyon)

Mrs Herringham later wrote what followed: “I first visited Ajanta in 1906, and brought back a small watercolor sketch of some colossal figures. Mr Binyon, to whom I showed this, was so much impressed that I was encouraged in the notion of returning and making some careful specimen copies, in the hope that this might lead to a more fully organized expedition which could undertake a complete record.” But in copying the frescoes of Ajanta, Mrs Herringham had her forerunners—Major Robert Gill (1804-879), and John Griffiths (1837-1918). Though the copies of both Gill and Griffiths were consumed by fire in London, photographs of those of Griffiths were published in 1897 for the world to see. At the behest of the British Museum, efforts began again for copying the frescoes at the Ajanta Caves during the early twentieth century. After her first visit to India, Mrs Herringham made two more visits to India for copying the Ajanta Frescoes—in the winter of 1909-10 for about six weeks, and then in 1910-11, when she remained for more than three months.

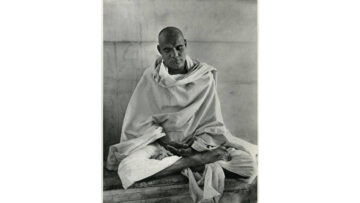

(Figure 3: Credit: DAG World – Asit Kumar Haldar)

Asit Kumar Haldar, one of the Bengal artists sent to work with Mrs Herringham, later wrote that in December 1909, when CJ Herringham came to Ajanta, he and Nandalal Bose joined her for assistance. Later on, when Dr JC Bose, his wife and Sister Nivedita visited the caves during Christmas and requested Mrs Herringham to take more artists from Bengal for assistance, K Venkatappa and Samarendranath Gupta went to work with her. This time, the team worked for three months. According to Mr Haldar, when Mrs Herringham returned to Ajanta in December 1910, only Samarendranath Gupta and Asit Kumar Haldar were sent to assist her.

(Read more in Part 2 – Sister Nivedita And Indian Art: The Pioneering Guidance)

References and Notes

- According to the Royal Historical Society’s Web portal, ‘Christiana Herringham was a significant figure in the British art world at the turn of the twentieth century. In addition to being an artist, she co-founded the Art Fund, wrote articles for the newly established The Burlington Magazine, headed up the tempera revival and championed Indian art, and campaigned for women’s suffrage.’ (https://royalhistsoc.org/calendar/christiana-herringham-and-her-circle/>accessed October 9, 2023). She married Wilmot Herringham (1855-1936), a doctor by profession, in 1880; he was knighted in 1914. Since the title was conferred after the period covered in this writing, we did not use it with the names of the couple. Mary Lago, her biographer, writes this about Mrs Herringham: ‘I learned that Christian Herringham was an expert copyist of quattrocento tempera paintings, that she visited India three times, and that two of those visits were for the purpose of copying the deteriorating wall paintings in the Buddhist caves at Ajanta.’ (Mary Lago, Christiana Herringham and the Edwardian Art Scene (Columbia, University of Missouri Press, 1996), see Preface, p. xi)

- Mary Lago, Christiana Herringham and the Edwardian Art Scene (Columbia, University of Missouri Press, 1996), pp.146-47, and 164.

- Christiana J. Herringham, The Frescos of Ajantà, The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs,Vol. 17, No. 87 (Jun., 1910), pp. 134 and 136-139): https://www.jstor.org/stable/858243> accessed September 10, 2023.

- John Keay, India Discovered (London, HarperCollins Publishers, 1981), pp. 153-54.

- https://royalasiaticsociety.org/john-griffiths-and-the-caves-at-ajanta/> accessed Aug. 21, 2023, and John Keay, India Discovered, p. 154.

- Lady Herringham with Essays of Various Members of the India Society, Ajanta Frescoes: Being Reproductions in Colour and Monochrome of Frescoes in Some of the Caves at Ajanta After Copies Taken in the Years 1909—1911 By Lady Herringham and Her Assistants (London, Humphrey Milford, OUP, 1915), p.16.

- Asit Kumar Haldar, Ajanta (Calcutta, Bhattacharya & Sons, 1920), see Introduction and Prelude.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.