The impact of his appearance at the Chicago religious parliament in 1893 had been so enormous, and justifiably so, that the reason which essentially took Vivekananda to the West has largely remained forgotten. But facts are there to prove that though his journey to the West had coincided with the timing of the religious parliament and, more so, the progressive youths of Madras were elated in convincing him to represent Hinduism at that great occasion—Vivekananda agreed to go for a different motivation. Let us examine the facts.

En route to Chicago, Vivekananda had a great impact on an erudite American lady named Miss Kate Sanborn while both were on the Canadian Pacific Railway’s Atlantic Express from Vancouver to Winnipeg. Less than a year after this meeting, Miss Sanborn wrote about the Swami in her memoir: ‘I had met him in the observation car of the Canadian Pacific… Most of all was I impressed by the monk, a magnificent specimen of manhood… with a lordly, imposing stride, as if he ruled the universe, and soft, dark eyes that could flash fire if roused or dance with merriment if the conversation amused him.’[1] She went on to highlight more of Vivekananda’s brilliance, ending with: ‘I told him, as we parted, I should be most pleased to present him to some men and women of learning and general culture, if by any chance he should come to Boston’ (ibid. 9).

Upon arriving in Chicago, Vivekananda discovered two things. Firstly, the religious parliament was not due to start for over a month. Secondly, the deadline for registering the name of any authorized representative had already passed. Despite this setback, he decided to take his chances and relocated to the more affordable city of Boston. While in Boston, Vivekananda recalled the invitation of Miss Sanborn. On 18 August 1893, he moved into her house in Metcalf, Massachusetts. Kate Sanborn later wrote that the Swami’s visit was not solely based on the need for accommodation, stating ‘… I received a telegram of forty-five words announcing that my reverend friend of the observation car was at the Quincy House,[2] Boston, and awaiting my orders’ (ibid. 9-10). Referring to her promise while they were on the Atlantic Express to introduce Vivekananda to people of academic excellence and financial means, Kate wrote that she welcomed him to her home and gave him directions to reach her address. Kate, however, failed to keep her promise as many people were on vacation during that time of the year. In her memoir, she expressed embarrassment when her visitor asked to meet the influential individuals. Despite this setback, her earnest initiatives eventually brought great results, but that’s a story for another time. Instead, we shall try to know whether Vivekananda expressed similar wishes to others before or after the religious parliament. We found a letter he wrote to his leading Madras disciple, Alasinga Perumal, on 20 August 1893, while he was staying with Miss Sanborn:

“Feel for the miserable and look up for help—it shall come. I have travelled twelve years with this load in my heart and this idea in my head. … With a bleeding heart I have crossed half the world to this strange land, seeking for help. The Lord is great. I know He will help me. I may perish of cold or hunger in this land, but I bequeath to you, young men, this sympathy, this struggle for the poor, the ignorant, the oppressed. … It is not the work of a day, and the path is full of the most deadly thorns. … Hundreds will fall in the struggle, hundreds will be ready to take it up. I may die here unsuccessful, another will take up the task.”[3]

Now the question is since when Swami Vivekananda, the spiritual seeker, made social reform his abiding goal. He wrote this about seven months later to one of his brother-disciples:

“A country where millions of people live on flowers of the Mohua plant,[4] and a million or two of Sadhus and a hundred million or so of Brahmins suck the blood out of these poor people, without even the least effort for their amelioration—is that a country or hell … I have travelled all over India, and seen this country too … My brother, in view of all this, specially of the poverty and ignorance, I had no sleep. At Cape Comorin sitting in Mother Kumari’s temple, sitting on the last bit of Indian rock—I hit upon a plan: We are so many Sannyasins wandering about, and teaching the people metaphysics—it is all madness.”[5]

In this letter, Swamiji explained his plans, and stated that the first thing they needed was men, and the next was funds. He was sure that, through the grace of their Guru, he could get from ten to fifteen men in every town. However, the question remained: why did he choose to raise funds overseas instead of trying in his own country? The answer also can be found in this letter, Vivekananda stated: ‘I next travelled in search of funds, but do you think the people of India were going to spend money! … Selfishness personified—are they to spend anything?’ (ibid. 255) He then explained that he came to America to earn money himself and then return to his country to devote the rest of his days to the realization of this one aim of his life. Nonetheless, Vivekananda was a proud Indian, he could not beg for his country, and his strategy reflects this:

“As our country is poor in social virtues, so this country is lacking in spirituality. I give them spirituality, and they give me money. I do not know how long I shall take to realise my end. . . . These people are not hypocrites, and jealousy is altogether absent in them. I depend on no one in Hindusthan. I shall try to earn the wherewithal myself to the best of my might and carry out my plans, or die in the attempt” (ibid.).

Let us go back again to the days before the religious parliament when Vivekananda delivered his first public speech in a church at Annisquam, a waterfront village located in Gloucester on the North Shore of Massachusetts. According to an eyewitness, in response to the Swami’s appeal, the New Englanders ‘solemnly contributed’ to the cause of the Swami—which was for a ‘heathen college to be carried on on strictly heathen principles.’[6]

After leaving Annisquam, Vivekananda visited Salem where he was graciously hosted by a renowned American lady. The Daily Gazette reported on his speech at the Wesley Chapel of Salem on 28 August 1893, stating that, ‘The speaker explained his mission in his country to be to organize monks for industrial purposes, that they might give the people the benefit of this industrial education and thus to elevate them and improve their condition’ (ibid. 49).

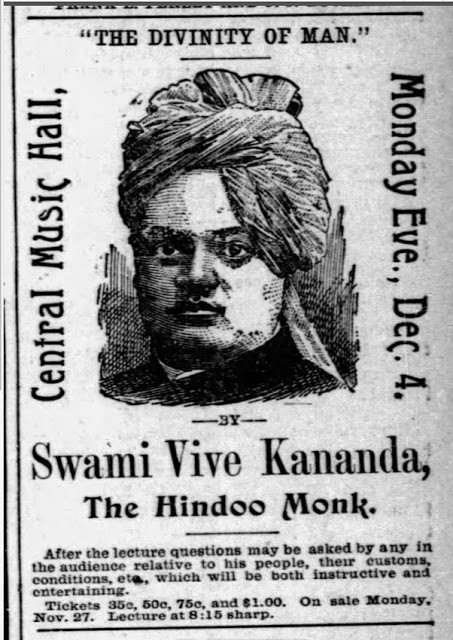

(Figure 1: Lecture announcement in Newspaper)

Vivekananda spent over three days in Saratoga Springs, New York before he finally reappeared in Chicago. In reporting his lecture at the meetings of the Social Science Association, the New York Times wrote,: ‘A most picturesque figure at these meetings has been the Hindu priest (Swami Vive Kananda), who has spoken at several of them upon the deplorable condition of the poor of India and some of the causes which bring it about.’[7] Everywhere he went, Vivekananda was evidently concerned about the plight of the poor and downtrodden in his country, and his mission was to help them. A member of the house where Vivekananda stayed as a guest during the religious parliament later reminisced: ‘When he began to give lectures, people offered him money for the work he hoped to do in India. … He was overwhelmed by the generosity of his audience who seemed so happy to give to help people they had never seen so far away.’[8]

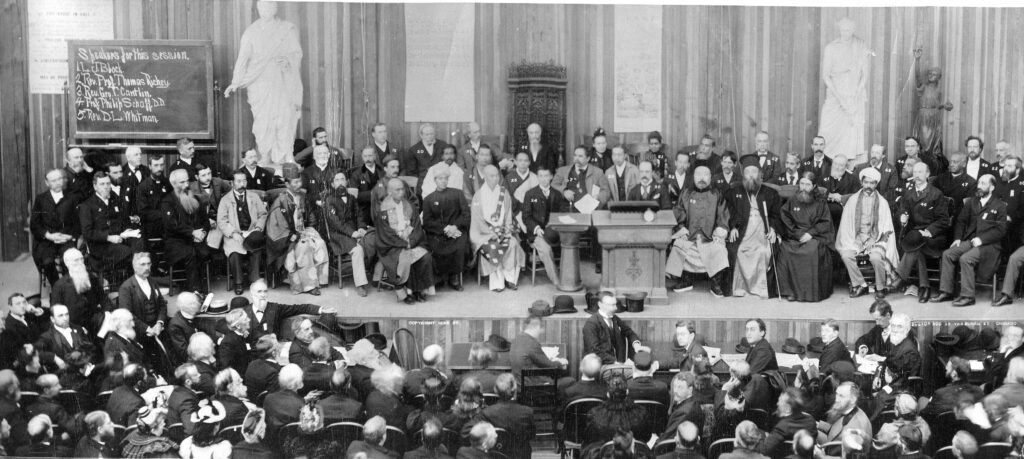

(Figure 2: Opening session of Parliament of Religions 11 September 1893)

When the Parliament of Religions was over and the hitherto unknown Indian monk became quite popular in the press and among the people—the Chicago Inter Ocean of September 1894 wrote what exactly he was doing: ‘… Vivekananda lingered in Chicago for several months after the great Parliament of Religions closed, studying many questions relating to schools and the material advancement of civilization in order to carry back to his own people as convincing arguments regarding America as he brought to this country concerning the morality and spirituality of his own people.’[9] Sometime after the religious parliament, the Swami visited the Cook County Normal School, which had Col. Francis Wayland Parker as its principal, now known as the prophet of American education. It shows how determined he was in his plan to make a difference.

In a letter to an Indian admirer on 28 December 1893, the Swami left no ambiguity about his visit to the U.S.: ‘I came to this country not to satisfy my curiosity, nor for name or fame, but to see if I could find any means for the support of the poor in India. If God helps me, you will know gradually what those means are.’[10]

Epilogue

While the religious parliament was in session, Vivekananda told the host lady of the house he was staying that, ‘he had had the greatest temptation of his life in America.’ When teased with the question: ‘Who is she, Swami?’ The record has it that, ‘he burst out laughing and said, “Oh, it is not a lady, it is Organization!”’[11] In January 1894, he wrote this to Alasinga Perumal in Madras: ‘Organize and found societies and go to work that is the only way.’[12]

This love for ‘Organization’ was soon inspired by another realization, for he said: ‘The miseries of the world cannot be cured by physical help only. … We may convert every house in the country into a charity asylum, we may fill the land with hospitals, but the misery of man will still continue to exist until man’s character changes.’[13] And soon he got the answer to the essential panacea for his foremost ambition—‘Man-making,’ he wrote: ‘Education, education, education alone! Travelling through many cities of Europe and observing in them the comforts and education of even the poor people, there was brought to my mind the state of our own poor people, and I used to shed tears. What made the difference? Education was the answer I got’ (ibid. 4.483).

Since late March 1894, Swamiji began to write to his brother disciples in Calcutta and the ardent admirers of Madras inspiring both to pursue in these lines with specific instruction that if the poor do not come to education, carry the same to their homes. And when he returned to India after his first Western visit, his words at the Victoria Hall in Madras on 9 February 1897 revealed the essence of his mission:

“I have a little will of my own. I have my little experience too; and I have a message for the world which I will deliver without fear and without care for the future. To the reformers I will point out that I am a greater reformer than any one of them. They want to reform only little bits. I want root-and-branch reform. Where we differ is in the method. Theirs is the method of destruction, mine is that of construction. I do not believe in reform; I believe in growth” (ibid. 3.213).

The Ramakrishna Mission is pursuing this charted path through their various organizations throughout the country and beyond. If more people and organizations can understand the essence of this objective and work towards expanding it, our country will face fewer obstacles that hinder our progress.

[1] Kate Sanborn, Abandoning An Adopted Farm (New York, D. Appleton And Company, 1894), 7-8.

[2] ‘The Quincy House, corner of Brattle Street and Brattle Square, is on the site of the first Quaker meeting-house in Boston. The original hotel has been extended from time to time, until it now covers more ground than any other hotel in the city. … The Quincy House is well furnished, and affords excellent accommodation for a first-class business house, the terms being only $2.50 per day.’ – See: King’s Handbook of Boston (Cambridge, Mass, Moses King Publisher, 1878), 46.

[3] Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda, 9 volumes, (Calcutta, Advaia Ashrama, 1-8, 1989; 9, 1997), 5.16-17. Hereafter CW.

[4] Mahua, also known as Madhuca longifolia, is a tree species native to India. It is characterized by its fragrant white flowers and large, ovoid fruits that contain edible seeds. The seeds are used to produce nutritious oil that is used in cooking and as a traditional medicine.

[5] CW, 6.254.

[6] Marie Louise Burke, Swami Vivekananda in the West: New Discoveries, vol. 1 (Calcutta, Advaita Ashrama, 1992), 39. Hereafter New Discoveries.

[7] September Days At The Spa, New York Times, 10 September 1893, http://query.nytimes.com/mem/

archive-ree/pdf?res=990DE5D8163EEF33A25753C1A96F9C94629ED7CF> accessed January 24, 2024-01-24

[8] Reminiscences of Swami Vivekananda – By His Eastern and Western Admirers (Calcutta, Advaita Ashrama, 1983) , 133 (see the reminiscence by .Cornelia Conger).

[9] New Discoveries, 1.159-60.

[10] CW, 5.27.

[11] Reminiscences of Swami Vivekananda, 133.

[12] Swami Vivekananda in Contemporary Indian News (1893-1902), ed., Sankari Prasad Basu (Kolkata, RMIC, 2016), 8.

[13] CW, 1.53.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.