In his formative years, William Ernest Hocking, later considered by many as the last of the Mohicans of Harvard University, was deeply confused after reading an extraordinary book. Much later, when almost in his final years of life, Hocking talked about how Herbert Spencer’s First Principles had devastated his early perceptions and thinking. Spencer’s arguments for evolution and rejection of belief in things that evade knowledge had much impressed him; nonetheless, the idea of man as just another animal—born, growing, mating, dying, and nothing more—was a vital injury to his prevailing sensibilities. Hocking also mentioned that his father had warned him against reading the book that had caused such mental distress.

According to what Hocking later wrote, his father, a devout Methodist, had many books for his “Sunday Reading,” which included Natural Law in the Spiritual World by Henry Drummond, a Scottish biologist. When Hocking was thirteen years old, he read this book and noticed frequent references to Herbert Spencer, an author he never knew till then. Intrigued, he thought of reading Spencer’s works and acquired his First Principle from the public library. He read it with increasing fascination, but unfortunately, his father caught him reading it one day and deemed it inappropriate for his age. Obeying his direction, Hocking submissively returned the book to the library. The next day, he borrowed it again and read in secret. Justifying the apprehension of his father, Spencer left a profound impact on young Hocking.

(Figure 1: The Art Institute of Chicago)

Turning just twenty in age, William Hocking visited Chicago to explore the possibility of admission at the newly opened University of Chicago. His visit coincided with the 1893 World’s religious parliament. Since Christianity was not the only religion to get attention there, he decided to go and listen to speakers from other traditions to gain insight that might relieve the tension in his mind.

Inspired by this aim, Hocking entered the Columbus Hall at Chicago’s Art Palace on the day Swami Vivekananda made his appearance at the religious parliament. In his memoir, Hocking later mentioned the impact of Vivekananda on the audience, saying that he spoke with calm authority and a sense of familiarity when he uttered: “Sisters and Brothers of America…;” the crowd, according to Hocking, responded with a thunderous wave of greeting, recognizing the speaker’s inner assurance. He also noted that Vivekananda spoke not as someone arguing from a tradition or, for that matter, any book that he might have read but from his own experience and certitude that posterity would always be indebted to him for.

It seems that Hocking was not only present on the day of Vivekananda’s inaugural speech, but also when he delivered a paper on Hinduism on September 19, 1893. Hocking mentions a powerful statement made by Vivekananda towards the end of the paper, which had an enormous impact on the audience. According to his writing, Vivekananda challenged the idea that all men are sinners, arguing that it is wrong to label people in such a way. Instead, he asserted that every individual possesses a divine essence that is undivided and eternal, and that this essence is part of the central being of each person, which is Brahman.

In narrating Vivekananda’s impact on him, William Hocking referred to the passage where he said: “Allow me to call you, brethren, by that sweet name—heirs of immortal bliss—yea, the Hindu refuses to call you sinners. Ye are the Children of God, the sharers of immortal bliss, holy and perfect beings. Ye divinities on earth—sinners! It is a sin to call a man so; it is a standing libel on human nature. Come up, O lions, and shake off the delusion that you are sheep; you are souls immortal, spirits free, blest and eternal…” Taken aback by this statement, Hocking found it to be a departure from his scientific psychology. However, he recognised that the Swami was speaking from his own experience and what he said justified consideration in any final worldview.

Even beside this memoir, in a letter to a close acquaintance who later edited a book on him, William Hocking wrote: “One incidental feature of the Chicago Fair was the first ‘Parliament of Religions.’ I made a great effort to get in for a crowded session at which a Hindu was to speak. I heard Swami Vivekananda, who at the climax of his appeal to think that something of Brahman is in each person called out ‘Call men sinners! It is a Sin to call men sinners!’’ Long after he had listened to Vivekananda, Hocking thought in retrospect: “I began to realize that Spencer could not be allowed the last word. And furthermore, that this religious experience of mine, which Spencer would dismiss as a psychological flurry, was very akin to the grounds of Vivekananda’s own certitude.”

Incidentally, Benoy Kumar Sarkar (1887– 1949), social scientist, professor and nationalist, offered his view about the utterance of Vivekananda: “… In just five words… he conquered the world, so to say, when he addressed men and women as, ‘Ye divinities on earth! – sinners?’ The first four words summoned into being the gospel of joy, hope, virility, energy and freedom for the races of men. And yet with the last word, embodying as it did a sarcastic question, he demolished the whole structure of soul-degenerating, cowardice-promoting, negative, pessimistic thoughts. On the astonished world the little five-word formula fell like a bomb-shell.” In this context we may note that according to online Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy: “The concept of sin is the concept of a human fault that offends a good God and brings with it human guilt. Its natural home is in the major theistic religions of Judaism, Christianity and Islam.” Perhaps in the prevalent backdrop of Higher Criticism, which questioned many biblical interpretations and inferences, this utterance gained a greater impact.

The great economic depression of America in 1893 ate away the fund Hocking had saved for his engineering education at the Chicago University. This made him go to Iowa State College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts in 1894 for a career in engineering. There, a chance encounter with a book of William James inspired him so much that he immediately decided to move East to study with William James at the Harvard University.

But before joining Harvard as a student, Hocking visited Cambridge in Boston. There, he met again with Vivekananda, staying then as a guest of Mrs Ole Bull at her Brattle Street residence. There again, the history repeated itself—for while at Mrs Bulls’s residence, the Swami delivered lectures and gave classes to eager aspirants. About his experience at Cambridge, Hocking wrote: “I spent four years in Davenport, earning money to come east and study with James. During those years, Vivekananda had begun his great work of founding centers for the Vedanta throughout America. In the course of this work he came to Cambridge. I heard him twice: once in a class in metaphysics, and once at the home of Mrs. Ole Bull on Brattle Street. It was in these informal gatherings that the quality of the man most directly spoke, and I was confirmed in my regard, and my purpose to re-think my philosophical foundations.” And such ‘rethinking’ of his ‘philosophical foundations’, left lasting mark on the life of William Hocking. In recounting his latter-day experience, he wrote: ‘My work with Royce, as well as with James, Palmer, Dickinson Miller, and others of the great department at the turn of the century, gave me the mental tools for conceiving a world unity in terms of spirit, rather than in terms of a redistribution of matter and motion.’

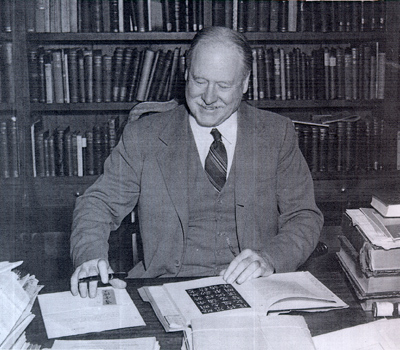

(Figure 2: Credit: Harvard Square Library – William E Hocking)

From 1902 to 1903, Hocking studied at Göttingen, Berlin, and Heidelberg before returning to Harvard University, where he was awarded his Ph.D. in 1904. Between 1906 and 1908, he remained with the University of California, Berkeley. Subsequently, Hocking served at Yale University as an assistant professor of philosophy (1908-1914) before returning to Harvard in 1914. In 1920, he became the Alford Professor of Natural Religion, Moral Philosophy, and Civil Polity. Barring intermitting assignments elsewhere, Hocking remained at Harvard until 1943, when he became a guest professor at several universities, including the University of Leiden in Holland (1947-1948), the Goethe Bicentennial in Aspen, Colorado (1949), Dartmouth College (1949-1950), and Haverford College (1950-1951). His Hibbert Lectures in 1936 were published later as Living Religions and a World Faith, and his Gifford Lectures also became a book titled Fact and Destiny.

Epilogue

Even after long years since he first met Vivekananda, Hocking could not forget him and his impact on his life. In his memoir, he expressed his admiration for Swami Vivekananda and his desire to visit India. He finally made it in 1931 and 1932 when he visited the Belur Math in Calcutta. Hocking’s association with the Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Movement continued through his connection with the Vedanta Centers. In 1944, in his foreword to Swami Nikhilananda’s translated Bhagavad Gita, he noted that the Bhagavad Gita was a crucial text for anyone who wanted to understand the religious aspirations of India. Today, we marvel the moment when the words of Vivekananda changed the mindset of a young American boy and inspired him to pursue philosophical quests without sacrificing his spiritual purview.

(Note: Abridged from author’s article William Ernest Hocking: A Turnaround Experience in the Prabuddha Bharata of December 2018)

Bibliography:

- Hocking, William Ernest, Recollections of Swami Vivekananda (Vedanta and the West, Vedanta Society of South California,Issue 163, September-October 1963), pp. 58-62.

- Leroy S. Rouner, Editor, Philosophy, Religion, And The Coming World Civilization: Essays In Honor of William Ernest Hocking (Maritinus Nijhoff, The Hague, Netherlands, 1966), p. 11

- The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda, Volume 1 (1989), p. 11.

- Philosophy, Religion, And The Coming World Civilization: Essays In Honor of William Ernest Hocking, p. 14.

- Sarkar, Benoy Kumar, The Might of Man in the Social Philosophy of Ramakrishna and Vivekananda (Sri Ramakrishna Math, Mylapore, 1936), p. 9 and 12.

- Philosophy, Religion, And The Coming World Civilization: Essays In Honor of William Ernest Hocking, p. 32.

- Philosophy, Religion, And The Coming World Civilization: Essays In Honor of William Ernest Hocking, p. 14.

- Besides what have been specifically referred to here, rest of the information about William Hocking’s life and activities are culled from the book entitled Philosophy, Religion, And The Coming World Civilization: Essays In Honor of William Ernest Hocking.

- Philosophy, Religion, And The Coming World Civilization: Essays In Honor of William Ernest Hocking, pp. XIII-XIV.

- Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy: https://www.rep.routledge.com/articles/thematic/sin/v-1> accessed February 20, 2024.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.