There are many episodes in the history of a country about which people are needed to be made aware of not just for their relevance as an important event from the past but also for their relevance in the present and implications for the country’s future in the event of lack of its awareness and understanding. Today’s topic is a classic example where the need for historical perspective is imperative.

This episode was the proposal of United Bengal in 1947. The proposal of territories of East and West Bengal together in Union as a sovereign nation and independent of India, this scheme was a brainchild of Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, former Prime Minister of Pakistan who at that point in time was the Premier of the province of Bengal.

Background

Ever since the late nineteenth century, political activity in India had gained momentum and all different regions of undivided India played varying degrees of role in it but Bengal had certainly been one of the most active provinces and in the tumultuous and divided politics of the province of Bengal of the post-1905 era, situations never seemed to calm down.

A major part in this stormy scenario was undoubtedly played by demography i.e. its huge population of Muslims where they were more than half of the province. During the anti-partition movement of 1905-1907 spearheaded by the Hindu population, methods like the call for Swadeshi, the Boycott Movement, the patriotic slogans like Bande Mataram had given a kick start in the province to patriotic sentiments.

The movement surely had Muslim presence to an extent, but it would be wrong to call it anything more than that for the presence was limited and the trajectory was already clear as a day with anti-Hindu riots of 1907 in the districts of Comilla and Jamalpur [1].

Willful negligence from the British authorities and support to the cause of the partition from the Nawab of Dacca, Salimullah played their role of intensifying the circumstances.

Separate electorates extended by the 1932 Communal Award had made things far more clear to the Hindu population of the province. After the general election of 1945-46, the Muslim League administration under the leadership of Suhrawardy discriminated against Hindus and many of its biased policies contributed immensely in creating a favorable opinion for the partition of Bengal. Its rampant favoritism towards the Muslim population and disregard for the life of Hindus was for everyone to see.

The Governor of Bengal at this time was Frederick Burrows. The Premier of Bengal had active support from the Governor. About Burrows, one writer had aptly said that he was “less of a crook than Herbert but was in league with Suhrawardy and was anxious to be as willing a tool for disruption as Herbert.” [2]

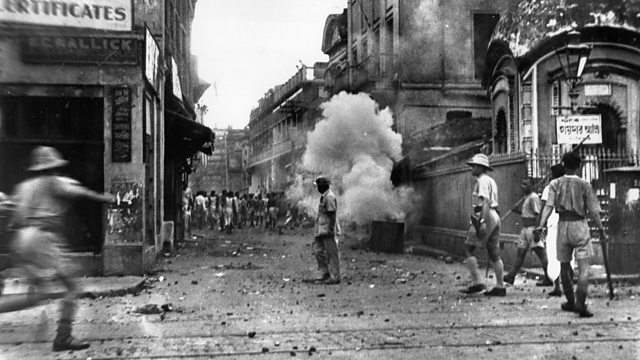

The support from Governor himself provided Suhrawardy with enough confidence to start one of the most gut-wrenching events of pre-partition India – the Great Calcutta Killings of 1946. It is a popular perception that the carnage against Hindus started on August 16, 1946, and raged for nearly four days up to August 20th but the truth is that the violence had erupted many a time before that year in and around Calcutta, even all round the country and had continued well into the next year. [3]

Direct Action Day declared by Jinnah was deliberately proclaimed a public holiday in Bengal and violence that raged had been planned by the League “meticulously..to the last detail, weeks in advance.” [4]

“It has also to be remembered that this was primarily a political manoeuvre and not the work of only the mullahs whipping up passions.” [5]

As to why is it necessary to understand this sequence of major events? Because they reveal the hypocrisy behind the argument for United Bengal Movement. The atrocities committed under the League-led government helps us to understand the magnitude of sheer vileness and hypocrisy of Suhrawardy and Jinnah’s campaign for United Bengal.

Genesis of the Idea

The plan, as has been mentioned above came from Suhrawardy but he was not alone in this scheme. During the short period of three months from April to June 1947 when the idea gained some traction, it was supported by even Sarat Chandra Bose and K. S. Roy though the intentions of both Bose and Roy were quite different from the League members which we will discuss below.

On February 20th, 1947, Prime Minister of Britain, Mr. Attlee made an announcement in the House of Commons about the transfer of power in Indian hands by a date not later than June 30th, 1948. The result was that the uncertainties especially in the provinces of Bengal and Punjab multiplied overnight.

If the events of 1946 had confirmed anything to a large part of the population, it was that the partition was not a matter of if but rather when. The March 8th announcement of the Congress Working Committee stated that in the event of the partition of India, the partition of Bengal and Punjab would follow. [6]

The Hindu Mahasabha on its end had earlier stated Akhand Hindustan as its goal but even they could foresee especially after Noakhali anti-Hindu riots that there was no other way for security and survival of Bengali Hindus other than partition.

Gandhi had been wary of the partition of the country but his resolve on this issue had weakened over time and in February when Syama Prasad Mukerjee met Gandhi in his Sodepur Ashram about the partition of the province of Bengal even he could see rationality in the scheme of Syama Prasad, [7] albeit reluctantly. The camps were now clearly drawn in this saga.

Through the Great Calcutta Killings, Suhrawardy had in fact tried his best to ‘rein in’ the Hindu population of the province but with the prospect of partition looming large, he decided to shift his policy towards the new gimmick of United Bengal. At a press conference at Delhi on 27th April 1947, he announced his plan for “an independent, undivided and sovereign Bengal in a divided India as a separate dominion.” [8]

Though the announcement of his plan was made in April, he had already started thinking along these lines after the February announcement in which Attlee had left enough room for maneuvering by saying that the transfer of power would be there even if it meant “in some areas to existing Provincial Governments.” [9] Suhrawardy could now see a way to get a piece for himself out of this pie.

The Hoax

A cloak of an economic necessity was used by the Bengal Premier to cover the plan of having an entire Bengal to himself after the British. As per him, Bengal was economically backward because of the presence of a large number of non-Bengali businessmen who exploited the hapless Bengalis and grew their business at their cost.

The plan was quite ingenious actually. Such clever use of ethnocultural differences, of pitting one Indian group against the other and using language as a dividing force had been a time tested stunt. The same was being applied in this case.

There is no denying that the large business groups had many times exploited its laborers. But instead of making sure that it doesn’t happen by creating an environment where businessmen and laborers both could flourish, the argument was as usual made against the very existence of large businesses themselves, something that even the Indian State after 1947 can be accused of.

The deliberate targeting of ethnicity was not because of Suhrawardy’s sympathy for the hapless Bengali, after all, it was the same Bengali that he had no problem getting gutted in the streets of Calcutta a few months back, but as mentioned before, he was playing divide and rule of his own.

Bengalis against the others, the capitalist against the labourer, the classic toxic cocktail of anarchy that is still used time and again while conveniently forgetting the other major difference i.e. religion which had been the basis of all major violent clashes of the region in its past.

Response from the Business Class

Another important personality who understood this duplicity was G. D. Birla, one of the most prominent businessmen of India whose connections to the Indian National Congress are very well known. He could foresee the charade for what it was. And that’s why he had been in support of the partition of Bengal from the very start.

Though it can be argued that he was able to see the net positive results that his business would get by remaining as part of India with access to the rest of the large Indian markets, it cannot be denied that he was also certainly going to lose huge share of business with great losses in Eastern Bengal. It is therefore to his credit that he saw the demand of united Bengal for what it really was – a hoax. But he wasn’t the only one.

Other businessmen like “B. M. Birla and B. L. Jalan, Bir Badridas Goenka, N. R. Sarkar, and other industrialists considered Indian Union as one economic unit and therefore were determined to keep West Bengal within this union.”

“G. D. Birla in his letter to AICC insisted on partition because the Suhrawardy -sponsored united Bengal campaign was a ploy to create a greater Pakistan.”

– Bidyut Chakrabarty, The Partition of Bengal and Assam, 1932-47, Contour of Freedom.

Scrambling for Allies

Suhrawardy, therefore, started collecting allies for his cause. One of the most vocal ally for the cause of United Bengal was Sarat Chandra Bose, brother of Subhash Chandra Bose, and a member of the Forward Bloc along with the Bengali Congress member Kiran Shankar Roy.

Though Roy was brought back to the Congress line after some serious advice from Sardar Patel in May 1947, it is interesting to note that Roy had even threatened to resign if his demands were not met with and this threat which was promptly ignored by the Congress High Command.

Sarat Chandra Bose had been imprisoned during the course of the second world war and during this time, he seemed to have come to the conclusion that the future of India was as “a Union of Socialist Republics – an immense melting pot in which the character of all races and nationalities comprised in it will be mixed and out of which a new worldism will arise which will recognize, no frontiers, no races and no classes.” [10] He was also of the view that partitioning of the provinces would make them “happy hunting grounds, for imperialists, communalists and reactionaries” and that it would “dissolve the linguistic bonds”. [11]

As one can see from these arguments, there is significant Marxist-Communist influence which seemed to have been accentuated during his prison time.

There is no doubt that he made these arguments for the betterment of the Bengali people in a way that he considered appropriate but there is also no denying the redundancy of this line of thought which looks more apparent in today’s time as I am sure it must have looked to many even in those times.

Despite the fact that his intentions were anti-Pakistan, they were quite myopic. Seeing the opportunity for gaining an influential ally, Suhrawardy started negotiating with the Bose camp for deciding the formal agenda of the United Bengal.

This also incensed Sardar Patel because both Bose and Roy had negotiated with Suhrawardy without the approval of its provincial Congress unit.

By the month of May, Suhrawardy’s United Bengal camp formally involved Bose and another Leaguer, Abul Hashim. Together they had even tried to enlist the support of Gandhi and had met him to sought his suggestions. [12]

They did receive some positive assurance from Gandhi for the United Bengal scheme because theoretically, it meant going against Jinnah’s “two-nations” demand and Gandhi wanted to oppose the two nations’ theory at any cost.

It is amply clear that for anyone concerned about not only the territorial integrity of India that was to emerge out of the chaos of 1947 but also worried about the plight of Hindus of Bengal, the entire scheme looked like political Russian roulette.

Now, all Suhrawardy had to do was to get the assent of Jinnah for this scheme. Earlier Jinnah had not been in support of a sovereign Bengal. From the very start, he wanted the entire provinces of both Punjab and Bengal to be part of his proposed Pakistan.

Realizing with the time that the partition of these provinces seemed real, Jinnah was perplexed. Pakistan with Eastern Bengal but without the crown jewel, Calcutta was not a welcoming prospect for him.

It was not that hard to convince Jinnah as one of the very close confidants of his, M. A. H. Ispahani (Ispahanis were one of the most prominent business houses of Bengal), seemed to be pulling the strings and even losing the strings of his purse for this campaign. He “persuaded Jinnah to discuss the matter with the Viceroy.” [13]

Amongst other reasons, Ispahani’s motives were financial. The jute industry of west Bengal which hitherto had been controlled by the “British business houses and the members of the Indian Chamber of Commerce” would be available for Ispahanis if the United Bengal scheme fructified. The fact that Calcutta would be part of West Bengal had caused serious alarm. It meant huge losses to the Ispahani business.

The need thus to keep Calcutta within the ambit of Pakistan prompted both Jinnah and Ispahani to support the demand of the United Bengal. Jinnah had stated: “If Bengal remains united, … I should be delighted. What is the use of Bengal without Calcutta[?]; They had much better to remain united and independent; I am sure that they would be on friendly terms with us”. [14] But what exactly he meant by the term ‘friendly’ will be discussed later in this write-up.

The Contradiction

But there was one hiccup. What about the Lahore Resolution for Pakistan of 1940 that had been the bedrock of the Muslim League’s growing popularity in India? Wouldn’t the demand of an independent nation be contrary to it?

The United Bengal demand thus ruffled a good amount of feathers within the League. Some Leaguers like the Khwaja Nazimuddin (Nawab of Dhaka) group raised their voices against this plan. Unsurprisingly, this schism had a history.

The Khwaja group had been sort of a rival within the Bengal Provincial Muslim League (BMPL) to the Suhrawardy group. After the departure of Fazlul Haq from active politics, Suhrawardy had been the principal opponent of the Khwaja group.

The difference between them ranged from class to culture. Suhrawardy though financially very strong had cultivated an image of representing the Bengali Muslim middle class while the Khwaja group represented the non-Bengali Muslim landed aristocracy. The ascent of Suhrawardy with tacit support from Jinnah to the Premiership of Bengal cemented a lot of differences.

The answer to the Lahore Resolution question vis-à-vis United Bengal was promptly provided from the Suhrawardy group by Abul Hashim. It was now stated by them that the Lahore Resolution was never about Akhand Pakistan anyways. As per Abul Hashim –

“It stipulated that the areas in which the Muslims are numerically in a majority as in the North-Western and the Eastern Zones of India should be grouped to constitute ‘The Independent States’ in which the constituent Unit shall be autonomous and sovereign……In Akhand Pakistan they would be under the domination of West Pakistanis and Urdu would be the state language. They could not expect a better position than becoming peons under Urdu speaking judges and magistrates.” [15]

As one can see, this argument was quite a prophecy in regard to intra-Muslim politics that culminated in a battle royale in 1971 with the deciding role played by the Indian State.

But the arguments against United Bengal within the League died soon after it was confirmed that Suhrawardy’s demand had Jinnah’s support. The Khwaja group had to back off from their opposition and support the United Bengal scheme.

The Bengali Hindus

As for the Hindu minority of the province, the cultural differences and sentiments of Bengali Hindus were being provoked and pitted against other Indian groups as a red herring to make the scheme of United Bengal possible. But did they find any traction.

Not exactly. There is no denying the fact that some Bengali Hindus did seem to support the idea of a United Bengal as can be gleaned from Sarat Chandra Bose’s involvement and Kishan Chandra Roy’s short entertaining of this idea.

But even within these united Bengal supporting Hindus, the majority was towards a united Bengal but as part of the Indian Union.

Some did seem to have a romantic view towards the earlier days of the 1905 anti-partition movement and thus were reluctant to go against the very goal which had served as a sort of their initiation ceremony in politics.

An example of this line of thought can be gleamed from writings of Nares Chandra Sen Gupta’s An appeal to Sons and Daughters of Bengal in which he stated that “the continuance of a United Bengal freed from the canker of communal electorates and communal ministry, continuing as a member of the Indian Union…” was the need of the hour and he then went on to urge his fellow Bengalis to “strive and toil and fight for that rather than to seek a partition of the province which but forty years ago people considered to be an intolerable calamity.” [16]

16 Some others supported due to their concern for the trouble they thought the partition would cause to numerous Hindus who will be left in Eastern Bengal after the partition and various other practical difficulties that the idea of a population exchange might generate for both rich and poor Bengali Hindus of Eastern Bengal. In the hindsight, we can see that these concerns were very genuine and valid.

But the overwhelming majority of Bengali Hindus were in strong support of the partition of the province. To elaborate, many of them though very much attached to the cause of Bengali territorial integrity, could see the reality behind the romanticism of the 1905 anti-partition movement.

They knew that if the Bengali Hindus were to be part of the United Bengal scheme, their entire existence would be in jeopardy. Many of them realized early on that if their lives and property, culture, and religion had to survive, partition was the only answer. An example of this line of thought is a letter that was sent to Amrita Bazar Patrika as early as mid-January 1947 in a section started by the newspaper called “Homeland for Bengal Hindus”. It stated –

“Bengali Hindus must face the grim reality before them. If they do then they will see how the good deeds done by patriotic Bengalis in an earlier day are gradually being nullified by the Muslim-dominated administration of the province… The Bengali Hindus must have a home where they will be able to preserve their culture and adjust their administration to their needs.” [17]

It is clear that even if some section of Bengali Hindus entertained the thought of a united Bengal, they clearly did it as United Bengal which continues to be a part of the Indian Union, and unsurprisingly, Hindus who supported a sovereign United Bengal were in a very small minority.

The result was that by the end of April, almost all of the Bengali Hindus wanted a separate province of their own with a Hindu majority and wanted their province to be an integral part of the Indian Union.

For example, a poll was conducted in Amrita Bazar Patrika whose results published on 23 April 1947 removed any doubts if they still existed. The question asked by the newspaper in the poll was – “Do you want a separate homeland for Bengali Hindus?” 98.3% voted in favor and 0.6% voted against the division and as per the newspaper, 99.6% of Hindus & 0.4% of Muslims had replied to the poll. [18]

The Opposite Effect

There was another problem if only Eastern Bengal was to be a part of Pakistan without its western part. At that time, a large part of the industry of Bengal was situated in the western part of the province.

Having only Eastern Bengal would create serious economic deficiencies for the future of Pakistan. Its food security would be another matter of concern in the future and Jinnah knew it.

Hence as mentioned above, he supported Suhrawardy in his campaign for United and sovereign Bengal. But these arguments started having the opposite effect of strengthening the resolve of people in favor of partition.

Finally, Jinnah quite expectedly I must say, brought out the Scheduled Caste card and stated that in the event of a partition, Scheduled Castes would be at the “mercy of the caste Hindus in western and the other at the mercy of the Muslims in Eastern Pakistan.” His hopes though were dashed when it was pointed out to him that various Scheduled Castes groups in Bengal had submitted a memorandum in favor of partition. [19]

A Subsidiary Pakistan

The fact that there was an inherent contradiction in Jinnah’s arguments was not lost on the Viceroy Mountbatten. Jinnah supported the ‘two-nation theory’ in India but did not follow the same logic in the provinces of Punjab and Bengal. Mountbatten had stated that if he accepted Jinnah’s logic for the whole of India, he can’t just stop short at provinces (emphasis mine).

But to Jinnah’s credit, he still was able to persuade Mountbatten despite his reservations, to lobby for the United Bengal scheme. Mountbatten had even tried to convince the upper authorities to give exemptions to Bengal and allow it to become an independent state but his efforts were thwarted when Congress high command remained resolute on having partition.

Jinnah expected the proposed sovereign United Bengal to remain ‘friendly’ as mentioned earlier but in reality, it was just a sugar-coated word for the real deal which he and Suhrawardy had in mind. He reportedly stated his intentions to the Viceroy as well. His words were:

“with its Muslim majority, an independent Bengal would be sort of subsidiary Pakistan.” [20]

But there was a major roadblock in this United Bengal plan. Sarat Chandra Bose had stated in his agenda that the United Bengal would have a joint electorate, but Suhrawardy was obviously not forthcoming on this. He knew that agreeing for joint electorates would nullify the very argument of two-nation theory and thus refused to give his approval for it.

The result was that Bose disassociated himself from the scheme completely. But another interesting point is that Sarat Bose never till his death gave up the idea of two provinces of Bengal together in union. [21]

Apparently, the Bengal Provincial Muslim League had already started distributing pamphlets that depicted United Bengal as Azad Pakistan. [22] They wanted all of it, at any cost but when none of it seemed possible, at last Jinnah as a last resort, tried to get Calcutta for Eastern Pakistan but even that seemed impossible so by the end his only hope was to get Calcutta declared a Free Port.

We all know how that turned out. While it is a fact that finally Bengal was divided but it is also a fact that this is not at all what the Suhrawardy and Jinnah had in mind.

Much Needed Clarity

The contradiction was apparent between the demand of United Bengal at one end and two-nation theory at the other but the Muslim League wanted to use them simultaneously for furthering its own needs. This fact was brought out aptly by the Hindu Mahasabha leader Dr. Syama Prasad Mukherjee who single-handedly made the pre-partition movement a driving force in the province of Bengal. His statement provides a lot of clarity:

“..according to Jinnah, ‘Hindus and Muslims are two separate nations and Muslims must have their homeland and their own state.’ Therefore Hindus in Bengal who constituted almost half of Bengal’s population, ‘may well demand that they must not be compelled to live within the Muslim state.”

– B. Chakrabarty, The Partition of Bengal and Assam, 1932-1947 Contour of Freedom.

The Long Memory

Any hopes which were still lingering for the United Bengal scheme died after the June 3rd, 1947 announcement by the British Government in which the partition plan was finalized, and later the provincial assemblies also voted in favor of partition.

Though these events took place in the span of merely two months, the results were very far-reaching. In the long memory of the majority of the Hindus in Bengal, the Islamic rule of the province had always been remembered as that period of barbarism which no Hindu wanted to go back to.

The threat that their lives would be just as the second rate as they had been in the past many centuries was never so real as it had been in those final years before independence.

Had the Muslim League-led government given a civilized administration after coming to power in 1945, then that would have been a welcome surprise and may even had augmented the support for a United Bengal.

Though the support even then would have been for a United Bengal which would remain part of the Indian Union as has been discussed above. But the League behaved like it was expected to behave.

The carnage of anti-Hindu Calcutta Killings of 1946 proved beyond doubt that the fears of every Hindu were as legitimate as they had been for the last many centuries.

League’s blatant disregard and conscious persecution of Hindus made sure that the Hindu public of Bengal saw the hoax behind the constant hammering of ‘Bengaliness uniting different religions’ that Suhrawardy was trying to sell. United and sovereign Bengal were always going to be a subsidiary of Pakistan as Jinnah had said.

The plight of Hindus in Eastern Pakistan after 1947 and in Bangladesh after 1971 has vindicated every fear of those times. Ever since the decision of partition was announced, it is a rather shameful fact that the Indian State had disappointed in providing a sense of security and soothing the wounds of the Hindu minority in its both eastern and western neighborhood.

The welcome change in this policy through CAA is just scratching the surface. There is a very long road ahead.

The state of West Bengal itself has to fight its long and bloody history of communist rule. Even the current West Bengal government with its open support to Islamists has created a plethora of challenges for the Bengali Hindus.

And when it comes to their treatment of minorities, the current Islamic states of Pakistan and Bangladesh, no matter their chequered history and huge differences in economy, are still what we can say – different sides of the same coin.

Conclusion

In these rocky times, we therefore as aware citizens of this nation have to understand why and how we reached here. Why the demand for a united and sovereign Bengal was so vehemently rejected. And if this idea is again propped up by vested interests, then its history has to be etched in minds of every concerned Indian, Bengali or not, that this United Bengal scheme even at that time was nothing but a stratagem of creating a Greater Pakistan by other means.

References

- History and Culture of the Indian People (Struggle for Freedom), Volume XI.

- Mitra, A. (1990). The Great Calcutta Killings of 1946: What Went before and After. Economic and Political Weekly, 25(5), 273-285. Retrieved November 13, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4395903

- ibid.

- ibid.

- ibid.

- Roy, H. (2009). A Partition of Contingency? Public Discourse in Bengal, 1946-1947. Modern Asian Studies, 43(6), 1355-1384. Retrieved November 13, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40285016

- Chhanda Chatterjee, Syama Prasad Mukerjee, the Hindu Dissent and the Partition of Bengal 1932-1947.

- Bidyut Chakrabarty, The Partition of Bengal and Assam, 1932-1947 Contour of Freedom.

- ibid.

- De, A. (1976). SARAT CHANDRA BOSE ON INDIAN NATIONAL QUESTION: A PLEA FOR SOVEREIGN BENGAL. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, 37, 389-395. Retrieved November 13, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/44138998.

- ibid.

- ibid.

- B. Chakrabarty, Contour of Freedom.

- ibid.

- ibid.

- Roy, H. A Partition of Contingency?

- ibid.

- ibid.

- B. Chakrabarty, Contour of Freedom.

- ibid.

- De, Amalendu. Sarat Chandra Bose on Indian National Question

- B. Chakrabarty, Contour of Freedom

Featured Image Credits: BBC

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.