Some lands live more in imagination and fabled lore than on the physical planes of Earth, have more reality in their legends and mystical mysteries than in the dry pages of history and geography, exude such great power and magnetism that they draw pilgrims sacrificing life and limb just to reach their shores.

Such is Tibet.

Tibet, the forbidden land closed off to foreigners from its isolated reaches for thousands of years, an elusive yet enchanting destination for only the most daring adventurers and committed seekers, who sought in its caves and shrines, the secrets to the mysteries of life.

The Tibet I came to know, came from the adventure stories and decade-long spiritual quests narrated by the likes of Madame Alexandra David-Neel, Lama Angarika Govinda and Heinrich Harrer. In their pages, I pictured the looming magnificence of the Forbidden City of Lhasa, remote mountain shrines shrouded in darkness, a bleak landscape of towering mountains and crystalline aqua high altitude lakes, something stunning yet stark, a land of sky burials and eternal snows.

(Potala Palace)

And so, I can never forget the first moment that the mists parted and I caught a glimpse of the mountain ranges of Tibet from the airplane. Or when I first saw the massive edifice of the Potala Palace, the erstwhile residence of the Dalai Lama. Or the awe of tracing the pilgrimage circuit around the Jokhang Temple, the holiest temple in all of Tibet, wreathed in clouds of juniper incense, with the somber march of traditionally dressed pilgrims circumambulating the temple, many who walked for weeks to reach the temple during the Saga Dawa (the holy lunar month in which the birth, enlightenment and passing of the Buddha is celebrated in Tibet).

(Pilgrims circumambulating Jokhang Temple)

(Jokhang Temple)

It is impossible for me to describe what I felt in Tibet, the impact that it had upon me. As a traveler, a lover of culture and history, it was a revelation. How paltry is the history we are taught in schools. We learn of petty squabbles over territory in Europe of the middle ages, but we never learn of the magnificence of the ancient civilizations like Egypt and Tibet, civilizations that stretch back into the distant mists of time. We study kings, who controlled puny swaths of territory in England and France, but not emperors, who ruled over Tibet, whose territory is roughly the size of Western Europe.

The weight of this history could be felt in the hall of the Dalai Lama’s tombs in the Potala Palace. This hall contains funeral stupas with the remains of several of the past Dalai Lamas. The Dalai Lama is a lineage of incarnations, who act as the spiritual and temporal ruler over the people and land of Tibet. The tombs themselves are magnificent – the central stupa towers 49 feet high, constructed from sandalwood, coated in gold, and studded with 18,680 pearls and semi-precious jewels. More than the grandeur of the architecture and design, I felt the hushed awe of being in the presence of a continuous lineage of tradition that has bound together the fabric of Tibetan civilization itself for thousands of years, which has been the bedrock of spiritual and temporal authority for its people. In that hall, one can feel the weight of responsibility and gravitas of being the custodian of one of the greatest spiritual and civilizational heritages in the history of the world.

As captivating as the history of Tibet is, as gorgeous its lunar landscapes, that’s not what drew me to Tibet in the final analysis – ultimately, I came to Tibet not as a tourist, but as a pilgrim.

(Barkhor Square, Lhasa)

There is a natural kinship between Hinduism and Buddhism and nowhere is that more pronounced than in Tibetan Buddhism, whose founders were monks and sages from India, who brought the Buddha Dharma to Tibet and firmly established it there. Many of our deities are found within Tibet, albeit in different forms, and the practices of Tibetan Buddhism draw heavily from Tantra. The first books I read about the spiritual life were the memoirs of Alexandra David-Neel, Heinrich Harrer, Angarika Govinda and others, who were pilgrims to Tibet and spent years there practicing meditation and learning from the great masters. They inspired my own spiritual quests.

I have had for years a small Buddhist shrine alongside my traditional Hindu puja room, and that reverence for the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha has grown over time since my trips to Ladakh and some of the great Buddhist monasteries in Himachal Pradesh.

Yet, there was one force in particular above all others that drew me towards Tibet. The pull of Padmasambhava, Guru Rimpoche, revered as the Second Buddha, from India, who brought Buddhism to Tibet in the 7th century. Since I first read of him, heard of him, many years ago, I felt his pull, this fierce, demon-destroying, dharma-establishing, Tantric master, philosopher and yogi, who famously pronounced, “For anyone, man or woman, who has faith in me, I, the lotus-born, have never departed – I sleep on their threshold.”

A few months before my trip to Tibet, when I was sitting in meditation, I felt Padmasambhava ask me to come to Tibet. For me, Tibet was one of those momentous once in a lifetime journeys that I never felt quite prepared for, like Kailash-Manasarovar (which, of course, is also in Tibet, but feels separate to me). Something of a landmark moment that would thereafter divide my life into a before and after of sorts.

(Padmasambhava)

And indeed, Tibet did not disappoint. It is one of the most powerful voyages I have ever undertaken. I did not have the adventures of Heinrich Harrer, whose famous book, Seven Years In Tibet, details his incredible journey through Tibet. I did not experience supernatural magic and miracles like those recounted by Alexandra David-Neel. But my few days in Tibet were nonetheless epic and transformative for me and altered my life irrevocably.

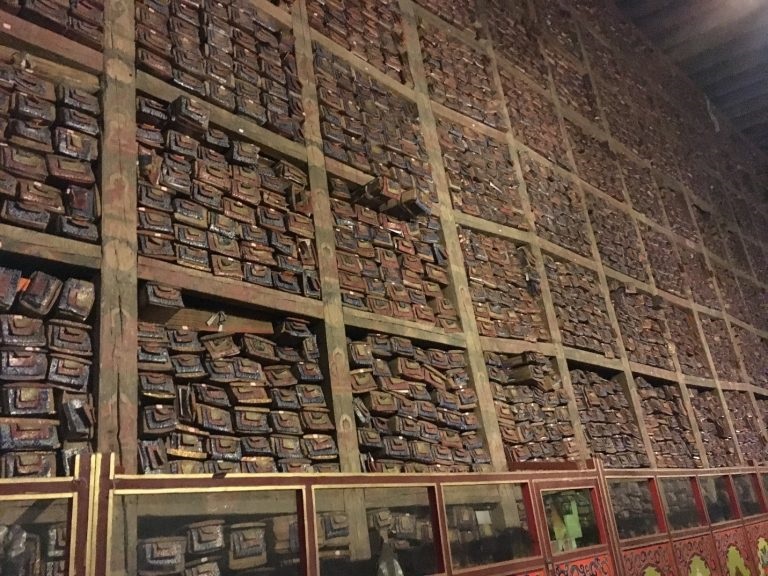

I visited many monasteries, several off the beaten path. Each had a history that was sublime yet marked with lament. China’s invasion of Tibet in 1950 spared no inch of ground, razing to the ground 70% of the monasteries then standing. Only a fraction have been rebuilt, and that too, only partially on a diminished scale. Monasteries that once housed several thousands of monks now only can support a few hundred. Monasteries that are prohibited today from carrying the picture of the Dalai Lama sometimes show photographs of how they looked before and after the utter destruction wrought by the Cultural Revolution. Nunneries, hospitals, schools, libraries, countless masterpieces of artwork and sacred images and statues – all destroyed without mercy.

(Photographs showing before and after the destruction of the Chinese invasion)

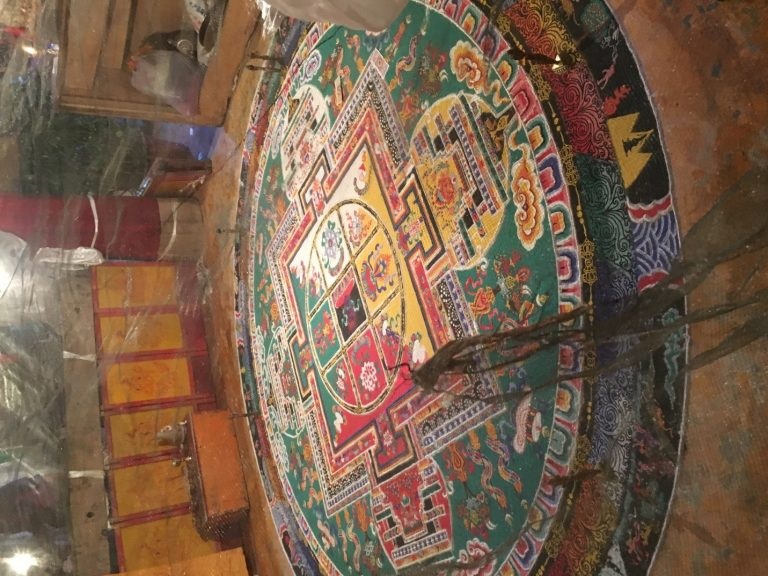

Yet, the monasteries still draw pilgrims from all across Tibet and are sites of enormous spiritual power. Meditation comes easily in their halls and their deities radiate fierce, sometimes wrathful power. And the monks, who live there tell wonderful tales of their history from an earlier time, monasteries established by yogis, who defeated demons terrorizing the locality, by monks and yogis, several who came from and studied in India from the 8th century onwards, spreading the light of Dharma – legendary figures like Padmasambhava, Shatarakshita, Atisha, and Marpa. They tell of miracles from ancient times and modern, of how the protectors of Tibet bless the land still.

(Mandala inside a monastery)

(In the middle is a deity of Tara, the goddess of compassion, who told the Bengali monk, Atisha, that if he left India for Tibet, he would shorten his life by twenty years, but he decided to do so anyway in his desire to spread the Dharma)

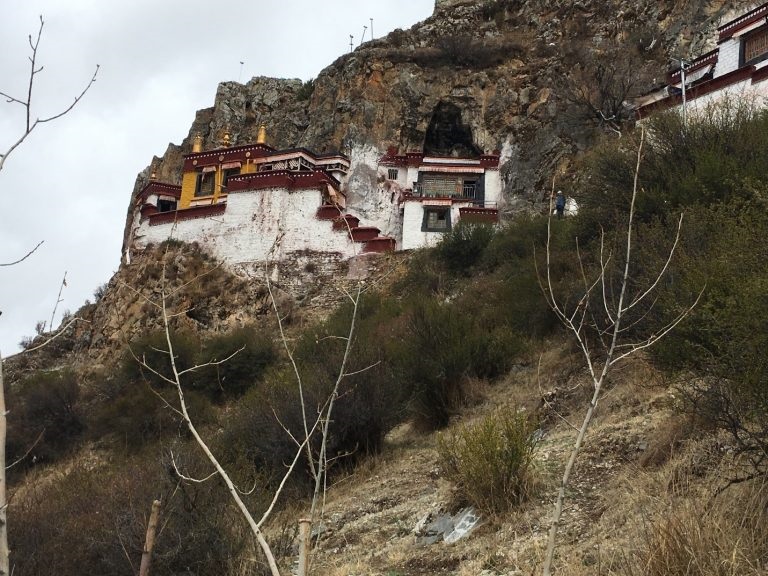

And I felt the power of those blessings myself, in monastery after monastery, from Samye (the first monastery established in Tibet) to those whose names I have since forgotten. One day, I visited Druk Yerpa, a remote valley outside Lhasa hosting a number of ancient meditation caves that used to house about three hundred monks. Some of the caves date back to the 7th century, where masters such as Padmasambhava meditated. When I meditated in his cave, sitting high in the mountains of Tibet, on the earth that had been touched by the footprints of millions of pilgrims over millennia, cradled in the land so sacred and secluded, so elusive for so long, I felt the fulfillment of all I had dreamt of about Tibet for so long. I felt a deep communion with Padmasambhava and felt his blessings shower upon me. In a few minutes of mediation, I felt more transformed than I have in years of sadhana. Those few moments by themselves were the fulfillment of all I searched for in Tibet, beyond the astonishing architecture and the fabled ancient civilization—the treasures that are unseen and intangible and can be felt only through the spirit. More grand than ascending the Himalayas is ascending the levels of inner consciousness to reach the heart of the atma.

That is the power of pilgrimage, the power of holy lands like Tibet.

(Druk Yerpa)

(Cave shrine at Druk Yerpa)

More than the majestic monasteries and the breathtaking mountain passes, it is in the silence of everyday moments in Tibet that one draws power and inspiration. The counting of beads on the mala, the slow steps of a kora (a circuit around a monastery or other holy place), the views of the pastoral yet stark countryside, the sips of butter tea, in each such moment, one breathes in the air purified and sanctified by the tapas and faith of millions of pilgrims and monks from time immemorial. In every moment, one is kept company by numberless bodhisattvas and devas and protected by the blessings of lamas and the protector kings, who have always been and shall always be the guardians and rulers of this unearthly realm.

As sublime and beautiful as my time in Tibet was, it was bittersweet, too. The reason I had dreaded that trip for so long was because I could not bear to see the oppression and destruction of this special, holy place. It was like being in India in the wake of it being ransacked, plundered, raped, looted and destroyed by the Moghuls.

(Library of manuscripts in Gyantse monastery – most of the texts of Gyantse, once one of the largest libraries in all of Tibet, were burned by the Chinese)

It is not just the temples and libraries and invaluable relics that have been destroyed. What we are witnessing today is the systemic wholesale destruction of a people and a way of life that is unique in the course of human history. Once lost, it will never be recovered. The Chinese are resettling Han Chinese all throughout Tibet on an unprecedented scale – indigenous Tibetans now make up less than half the population of Lhasa. Stores, hotels and tour agencies are now owned and operated by ethnic Chinese, crowding out Tibetan traditions, food and culture. Tour agents are strictly controlled and fed propaganda by the Chinese government on what falsified history to tell visitors and tourists as they visit monasteries and palaces. Tibetans, who want to become monks cannot do so if anyone in their family has been ‘politically active’ and cannot undergo monastic education until they are 18 years old, which strongly violates Tibetan religious tradition. Education as introduced by the Chinese is indoctrination in culture and values foreign to Tibet. In fifty years, Tibet as we know it will be gone.

India and Tibet have long shared kinship, a sharing of cultural and spiritual traditions. It was India, after all, that gave refuge to the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan government in exile. But the tale of what is occurring in Tibet today is a cautionary tale for India, too. Will India one day share Tibet’s fate? We must bear witness to the decline and destruction of Tibet today to ensure the same does not happen to India. We must do what we can to support Dharma in Tibet and in India.

As I boarded the plane to leave Tibet for Nepal, I offered my homage to this land that will always be a sacred site of reverence for me – Farewell, Tibet. I shall never forget you. On your lofty peaks, I felt communion with the gods and boddhisattvas, who have protected this land from days of yore. Your temples brought me to the deepest recesses of my own consciousness. And the blessings on my life and spiritual development have been profound. My gratitude and prostrations shall always be with you. I shall never forget, too, the horrors that have been wreaked on your land and your people and a destruction so terrible it can never be fully recovered from. So long as I live, I shall pray that you once again reign free and proud, and every offering I make for Dharma shall be for you as well. Om Mani Padme Hum!

(This article was published by IndiaFacts in 2017)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.