Introduction

How old are the Vedic Hindu rituals? This article traces the roots of Vedic rituals archaeologically. It gives an overview of the archaeological evidence of Vedic rituals. It looks into the supposed claims regarding evidence of the practice of Vedic rites in bronze age steppe cultures which are seen as original Indo-Iranian or ancestral ‘Aryan’ cultures before they invaded or immigrated into India by the majority of Indo-Europeanists.

Based on the evidence from Vedic scriptures, the article also suggests that the existence of sacrificial fire worship reminding us of Vedic rituals in the bronze age Harappan or Sarasvati-Sindhu Valley Civilization (SSVC), and thus the Vedic fire rituals being among the oldest surviving religious rituals practiced by mankind.

Vedic rituals in the bronze age Eurasian Steppes?

The mainstream Kurgan hypothesis endorsing Aryan invasion/immigration theory (AIT) places origins of Vedic culture at around 1700-1500 BCE with the composition of Rig Veda. Proponents of Kurgan hypothesis states that the ancestral form of Vedic culture is traced from early stages of the bronze age steppe cultures like Sintashta, Andronovo etc which were near Ural mountains.

As evidence for Vedic rituals practiced in the steppes, noted Indo-Eurpeanist David W. Anthony states that the numerous horse burials found from Sintashta-Andronovo Kurgan (i.e. graves with tumulus mounds) burials represents Vedic Aśvamedha or horse sacrifice [1].

“The horse sacrifice at a royal funeral is described in RV 1.162: “Keep the limbs undamaged and place them in the proper pattern. Cut them apart, calling out piece by piece.” The horse sacrifices in Sintashta, Potapovka, and Ftlatovka graves match this description, with the lower legs of horses carefully cut apart at the joints and placed in and over the grave. The preference for horses as sacrificial animals in Sintashta funeral rituals, a species choice setting Sintashta apart from earlier steppe cultures, was again paralleled in the RV. Another verse in the same hymn read: “Those who see that the racehorse is cooked, who say, ‘It smells good! Take it away!’ and who wait for the doling out of the flesh of the charger-let their approval encourage us.” These lines describe the public feasting that surrounded the funeral of an important person, exactly like the feasting implied by head-and-hoof deposits of horses, cattle, goats, and sheep in Sintashta graves that would have yielded hundreds or even thousands of kilos of meat.”

But actually, the Aśvamedha ritual involves the horse being sacrificed and offered into the sacrificial fire as mentioned in Rig Veda 1.162.19, instead of being buried in the graves. The Aśvamedha ritual involves a fertility rite which is also focused on the prosperity and sovereignty of the kingdom. It has nothing to do with any graves or burials like we see in steppe cultures.

Also, the steppe graves often contained multiple horse remains while only a single horse is utilized in Aśvamedha ritual. So this identification of Sintashta-Andronovo culturesas being ancestral to Vedic culture based on Aśvamedha rite is absurd.

Another important argument made by Russian archaeologist E. E. Kuzmina is that certain hearths discovered from Andronovo zones resemble Vedic ritualistic fire altars [2].

“Andronovo houses were heated and illuminated by hearths of various types. Type 1 had an open round or oval fire-place, 0.7-3m in diameter, sometimes floored with stone. Such fires, that met both domestic and industrial needs, are found both inside and outside of houses. This type of hearth (gulkhan aloe) is known in Central Asia, first of all among the Iranian Tadzhiks and Pamiri, and is to be found in communal houses for men where it originated from early Iranian houses of fire (Pisarchik 1982: 72). Type 2 hearths comprise a shallow round or oval pit, 0.5-0.8m in diameter, sometimes more, 0.15-0.4m deep, and often covered with flat stone slabs on the bottom. This is the most widespread type of hearth and served for cooking, heating and lighting; it is similar to the Central Asian type of hearth known as the chakhlak or chagdon (Pisarchik 1982: 78, 79, 109 ). This hearth is described in ancient Indian texts as the domestic fire garhapatya- `fire of the master of the house’ (Mandel’shtam 1968: 126). Such hearths were used for ritual purposes: a bride would go around it, a widow would perform a funeral dance, people jumped over it during a feast. The gulkhan (hearth) from gut- ‘heat’ is preserved in the Iranian and Indian languages (Pisarchik 1982: 74-77, 105, 106). The third type of hearth has a rectangular form, from 0.7 x 1m to 1.5 x 2m, and was made of closely adjusted rectangular stone slabs inserted into the ground on their narrow ends. Such hearths were found in the center of a house, kept clean, and it is likely that they had a ritual function (Atasu, Buguly, Shandasha, Ushkatta 11, Spasskiy Most, Kent, Tagibay-Bulak, Dongal). This type of hearth corresponded to the early Indian special cult hearth ahavaniya (Mandel’shtam 1968: 126). Rectangular and round hearths have parallels in ancient Rome where the round hearth used for cooking was dedicated to the goddess of the domestic hearth Vesta; the square hearth was dedicated to male gods and the ancestors (Dumezi I 1954).”

As we can see, it is said that the hearths also contained stone slabs. While the Vedic altars are usually made of bricks or clay and has no relation with any stones or slabs like we see in Andronovo hearth. So there is no resemblance between Andronovo hearths and Vedic sacrificial altars.

While mentioned Vedic fire altars, it is also good to mention about the cremation of corpses which was prevalent in later phases of Sintashta-Andronovo culture called Fedorovo culture. Since Vedic people also practiced cremation, authors who argue in favour of Vedic Aryan homeland in the Steppes identify

Andronovo as representing the ancestral version of Vedic culture. But in reality, cremation was already widespread well before its attestation in Sintashta-Andronovo. The late SSVC Cemetery H culture practiced cremation and it certainly predates the later Fedorovo phase of Sintashta-Andronovo culture. Also even Anthony now admits that the cremation custom was picked up by the Andronovans from the pre-Andronovo local culture of Central Asia [3].

“The pre-Andronovo mortuary custom of cremation documented at Tasbas and Hegash continued into the Andronovo period as a distinctive trait of Fedorovo mortuary rituals in the Tien Shan region but with the addition of a kurgan, stone knees, and other Andronovo traits absent from the I3egash la and fasbas level I mortuary customs. At both sites. the earlier pre-Andronovo phase was followed in 1800 to 1500 BC by Andronovo styles of material culture. As the evidence now stands, it seems that the local pre-Andronovo cultures of the northern Tien Shan were absorbed into the Andronovo cultural interaction.”

Also, certain earlier Sarasvati-Sindhu sites like Tarkhanwala Dera also have evidences of cremation [4] and it became popular by the time of Cemetery H culture starting around ~1900 BCE, still earlier than the time when Andronovo-Fedorovo culture expanded further south from steppes.

Thus, it can said with confidence that the steppe cultures have no traces of Vedic ritualism.

Harappan fire rituals and its Vedic parallels

Now since none of the steppe cultures have any traces of Vedic ritualism, let us take our focus to the historic seat of Vedic Aryans, i.e northern India, and see if ancient cultures of this region have any traces of Vedic ritualism.

The most important evidence that we have to trace roots of Vedic rituals in SSVC is the discovery of fire altars from various sites like Kalibangan, Banawali, Lothal etc. The most crucial findings are from Kalibangan where we find parallels with Vedic ritualism as described in Vedic scriptures. As veteran Indian archaeologist B. B. Lal remarks [5]:

“ In one of the platforms there were contiguous ‘fire-altars’, running from north to south . Although a subsequent drain had destroyed some of the altars, it would appear that originally these were seven in number — whatever be the significance of that number. (It may, incidentally, be recalled that a seal from Mohenjo-daro shows seven devotees marching in a row, in the lower register, the upper one depicting a deity within a peepal-leaf enclosure.) Although because of subsequent disturbances, the contents of these altars had been depleted, one could nevertheless find in some of them the remains of stele, ‘cakes’ and charcoal, signifying that these served the same purpose as did the ‘fire-altars’ in the Lower Town, discussed earlier . On the west of these altars there lay the lower half of a jar in a pit, containing ash and charcoal. It would appear that in it fire was kept ready to be used in the altars. “

In another platform there was also a ‘pit’ altar (cf. Agni ‘kuṇḍa’) lined with bricks, just like Vedic altars [6].

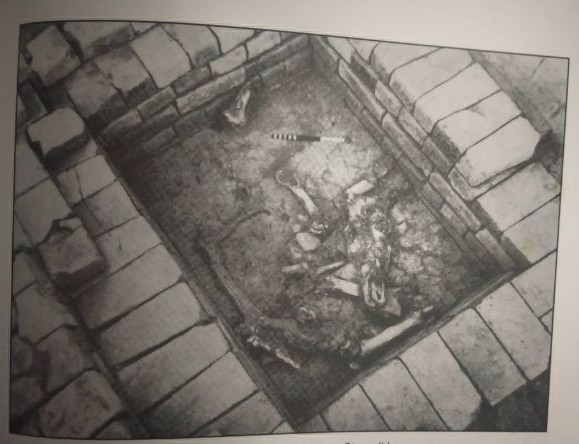

Fig. 1 : Fire ‘pit’ altar from Kalibangan along with bricks

“On another platform in the southern part of the Citadel there was a pit lined with kiln-fired bricks. It measured 1.5 x 1 m and contained bovine bones and antlers, indicative of animal sacrifice. How the animal was carried to the sacrificial altar is indicated by engravings found on a terracotta ‘cake’ at Kalibangan itself.”

Also at Kalibangan there was a bathing area nearby the altars which indicates practice of purificatory ritual bathing which is also part of Vedic rituals [7].

“Close by on the north-west of the fire-altars, there were a well and a bathing platform, further suggesting that a ceremonial bath prior to the performing of the ritual may have been a part of the ceremony.”

For instance in Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa 12.9.2.1 describes about ritualistic bathing [8].

Having performed the sacrifice they betake themselves to the purificatory bath; for after a Soma-sacrifice they do betake themselves to the purificatory bath, and the Sautrâmanî is the same as the Soma (sacrifice).

Another thing is that the altars were positioned eastward direction. [9]

“Another interesting feature was that of a north-south wall running behind the row of the fire-altars. This would show that the person(s) using these altars had to face east while carrying out the ritual.”

So too, in various places of Rig Veda we find that the ritual oblations were made in eastward direction. For example Rig Veda 3.1.2, 5.28.1, 3.6.1 etc [10].

Agni inflamed hath sent to heaven his lustre: he shines forth widely turning unto Morning. Eastward the ladle goes that brings all blessing, praising the Gods with homage and oblation.

Rig Veda 5.28,1

East have we turned the rite; may the hymn aid it. With wood and worship shall they honour Agni. From heaven the synods of the wise have learnt it: e’en for the quick and strong they seek advancement.

Rig Veda 3.1.2

Urged on by deep devotion, O ye singers, bring, pious ones, the God-approaching ladle. Borne onward to the right it travels eastward, and, filled with oil, to Agni bears oblation.

Rig Veda 3.6.1

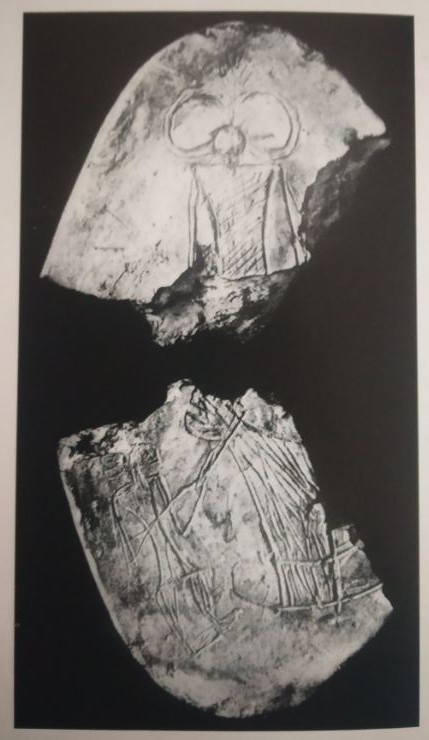

Also a terracotta cake discovered from Kalibangan same site depicts a man holding an animal with a noose tied in it’s neck.

Fig 2: Ritualistic terracotta cake from Kalibangan

In Vedic rituals, the animals were sacrificed by suffocated them with noose, as cited in Vedic ritual texts like Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa 3.7.4.1 [11].

Having made a noose, he throws it over (the victim) with (Vâg. S. VI, 8), ‘With the noose of sacred order I bind thee, O oblation to the gods!’ for that rope, forsooth, is Varuna’s: therefore he thus binds it with the noose of sacred order, and thus that rope of Varuna does not injure it.”

One side of the cake also depicts the Harappan horned divinity. This indicates that the animal must’ve been sacrificed to the horned divinity. Same horned divinity can be seen in the famous Harappan ‘Pashupati’ seal [12].

Fig.3 : The famous Harappan ‘Pashupati’ seal

All these indicates practice of Vedic rituals in this Harappan city. Mainstream Indologists have been skeptical about these structures being Vedic altars, they say these are just cooking hearths. But if this is true, why animal bones are inside the altar?

Obviously, no one will cook animal by directly throwing the flesh with bones inside the hearth since it would be mixed with charcoal, they would cook it in a vessel which is kept above the hearth.

Archaeologist J. P. Joshi remarks [13]

“Bones recovered from the altars include those of bovines, zebu, goat or sheep, and deer.”

The fact that animal bones are found inside confirms that these were indeed ritualistic fire altars with animal offerings. Further the depiction of horned divinity in the terracotta cake found from the site further confirms it’s ritualistic nature, rather than it being mere cooking hearth. Even western Indologists like Asko Parpola who prefer non-Aryan Dravidian authorship of SSVC finds parallels in Vedic tradition and Kalibangan altars [14].

“The seven ‘fire-altars’ at Kalibangan are closely paralleled by the dhiṣnya hearths of the Vedic Soma sacrifice. Six of these hearths are in a north-south row inside the ‘sitting-hall’ (the priests sit to the west of them, facing east, as at Kalibangan). They belong to six priests, while one more priest (the ‘fire-kindler’) has a fireplace of his own to the north of the others, on the border of the sacrificial area. The seven officiating priests who have a special dhiṣnya are also known as ‘the seven sacrificers’ (sapta hotrāh).”

British archaeologists Raymond and Bridget Allchin also states that the entire complex from Kalibangan was ritualistic in nature. [15]

“The brick platforms are separated from each other by narrow brick-paved passages. Their surfaces had been damaged, but on one there was a row of seven of the distinctive ‘fire altars’, found also in the houses of the lower town, as well as a brick-lined pit containing animal bones and antlers, a well head and a dram. There seems to be little doubt that this complex marked a ritual centre where animal sacrifice, ritual bathing and perhaps also the cult of sacred fire took place”

They also doesn’t rule out presence of Vedic Aryans in mature Harappan urban phase based on Kalibangan finds [16].

“At Kalibangan the curious ritual hearths (if they indeed are so) reported in domestic, public and civic situations are suggestive of a practice ancestral to the Indo-Aryan fire sacrifices, and it is tempting to see this as an indication of the presence of Indo-Aryan speakers already during the Harappan urban phase.”

It is also important to note that we also find ‘pit’ altars built during early historic period. For instance there is a recent find of fire altar from Malhar dated to Satavahana era. This fire altar has close parallels with early Harappan altar from Kalibangan, though it is shaped differently like a Tantric Yantra inside [17].

Fig.4 : Remains of altar from Malhar

A Harappan apsidal ‘fire temple’ and it’s connection with later apsidal temples.

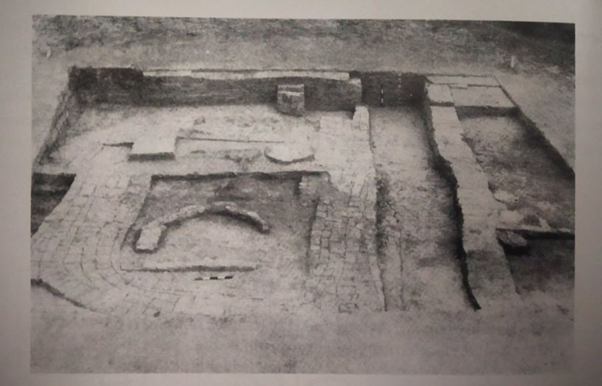

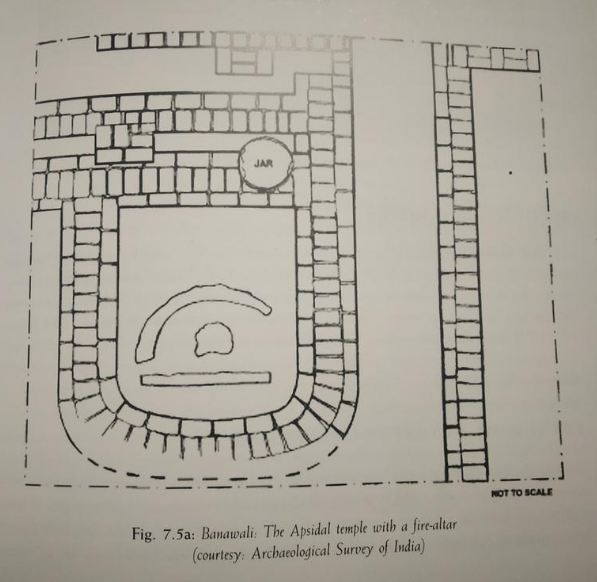

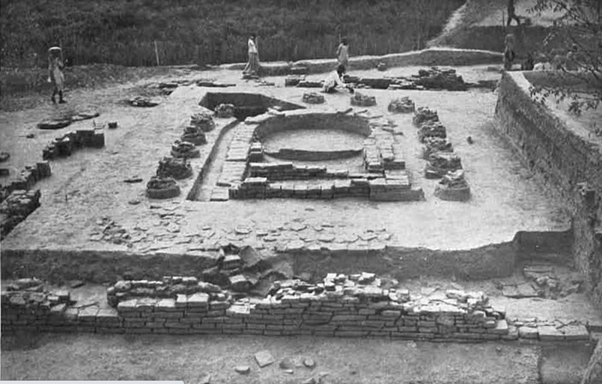

Also there is an interesting find of the remains of an apsidal ‘fire temple’ from SSVC site of Banawali. This structure was also made of bricks and inside this structure we also see a semi-circular altar reminding us of Vedic Dakṣiṇāgni altar along with ashes, which would’ve been used to conduct fire rituals just like in Kalibangan [18] [19].

Fig.5 : Remains of ‘fire temple’ from Banawali.

Fig.6: Plan of Banawali ‘fire temple’.

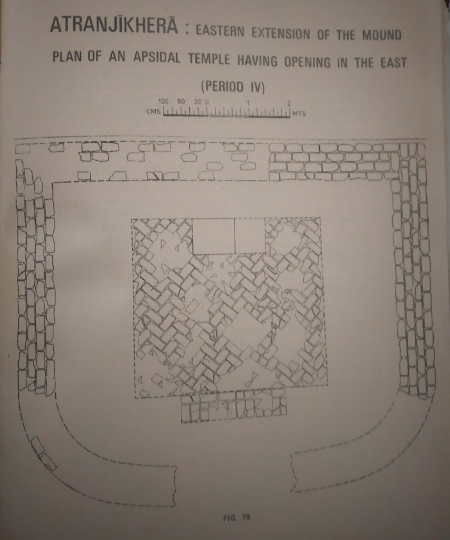

We see an exactly similar apsidal brick temple like the one from Banawali later in Atranjikhera site dating to Mauryan-Shunga era [20].

Fig.7: Plan of apsidal temple from Atranjikhera

Both of these have clear resemblance and are made of bricks like the Vedic and Kalibangan altars. Other early temples also had apsidal plan. For instance the Naga temple made from bricks discovered at Mathura is also in apsidal plan [21].

Fig.8: Remains of apsidal Naga temple from Mathura

It is not unreasonable to think that the tradition of building apsidal structures of early historic India has it’s roots in earlier Harappan tradition. While the Harappan one was used for fire worship, the later ones were dedicated to different deities. It could be possible that such early shrines evolved directly out of Vedic altars since the very term Caitya, referring to early shrines or temples, is derived from the term Citi or fire altar. The Banawali fire temple would represent this evolution of fire altars into shrines where rituals are conducted.

Conclusion

To conclude, it is an irrefutable fact that the Harappans had fire worship. We do not know which exact Vedic rite was practiced in SSVC sites, but undoubtedly there are obvious parallels between Vedic ritual setup and entire theme of finds from sites like Kaibangan. Along with Banawali find, this is a clear evidence for the undeniable fact that the Harappans practiced fire rituals.

Perhaps the fire rituals performed here may even have been Indo-Iranian in nature, ancestral tradition to later Vedic rituals which were evolved out of it. This is far better evidence for practice of Indo-Iranian fire rituals than imaginations of Kurgan theorists who see Vedic Aśvamedha in horse burials of the steppes and Vedic altars in hearths with stone slabs.

We should trace the roots of Vedic rituals in SSVC rather than in steppe cultures which shows no trace of Vedic ritualism based on sacred fire.

With these parallels between Vedic rites and Harappan rites, we can push back the date of Vedic era and roots of Vedic ritualism prior to 1700-1500 BCE, the traditional date for the early Rig Vedic era as given by most Indologists and historians as per AIT chronology, to the mature Harappan phase of SSVC going beyond 1900 BCE, starting around 2600 BCE.

Thus the Vedic rituals represents the oldest surviving ritual of mankind, with continuity right from the bronze age to modern times. After all, even the simple Homa fire rituals done daily in various temples and homes ultimately derive from Vedic fire rituals! It is a living tradition practiced right from the bronze age during 3rd millennium BCE at least.

Bibliography

- Anthony, David W. (2007), The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World, Princeton University Press, Kuz’mina

- Elena Efimovna (2007), J. P. Mallory (ed.), The Origin of the Indo-Iranians, Brill

- Anthony, David W.; Brown, Dorcas R.; Khokhlov, Aleksandr A.; Kuznetsov, Pavel F.; Mochalov, Oleg D. (2016). A Bronze Age Landscape in the Russian Steppes: The Samara Valley Project. Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press

- Gregory L. Possehl (11 November 2002). The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective. Rowman Altamira

- Braj Basi Lal (2015). The Rigvedic People: ‘Invaders’?/’Immigrants’? or Indigenous?. Aryan Books International.

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Eggeling, Julius (1882–1900). The Śatapatha-Brāhmaṇa, according to the text of the Madhyandina school. Princeton Theological Seminary Library. Oxford, The Clarendon Press.

- Braj Basi Lal, Op. cit.

- Griffith, Ralph Thomas Hotchkin (11 April 1896). The Hymns of the Rig Veda. Kotagiri Nilgiri.

- Eggeling, Julius (1882–1900). The Śatapatha-Brāhmaṇa, according to the text of the Madhyandina school. Princeton Theological Seminary Library. Oxford, The Clarendon Press.

- Wikimedia commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Shiva_Pashupati.jpg

- Joshi, Jagat Pati (2008), Harappan Architecture and Civil Engineering. New Delhi : Rupa & Company, Infinity Foundation series.

- Parpola, Asko (1994), Deciphering the Indus script Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Allchin, Bridget, and F. Raymond Allchin 1982. The Rise of Civilization in India and Pakistan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ibid

- Indian Archaeology 2010-2011 – A Review, Chief editor Rakesh Tewari, Editors D.N. Dimri & Indu Prakash

- Danino, Michel (2010), The Lost River – On the trail of the Sarasvati, Penguin Books India

- Joshi, Jagat Pati, Op. cit.

- Gaur, R. C. (1983) : Excavations at Atranjikhera. Early civilization of the Upper Ganga Basin. Delhi: Motilal Banarasidass

- Wikimedia Commons https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Sonkh_Apsidal_Temple.jpg

We thank our consulting editor Surendranath C. for the contribution of this article.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.