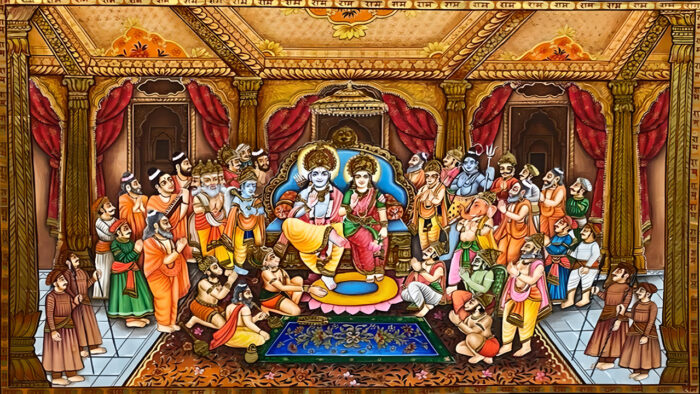

“The consecration of the Ram Mandir marks a turning point for India. The temple is a symbol of India’s unifying ethos” –

Dr. Makarand Paranjape

रमन्ते योगिनोऽनन्ते सत्यानन्दे चिदात्मनि

इति रामपदेनासौ परं ब्रह्माभिधीयते

(ramante yogino’nante satyānande cidātmani

iti rāmapadenāsau paraṃ brahmābhidhīyate)

(The Supreme Absolute Truth is called Rāma because the transcendentalists take pleasure in the unlimited true pleasure of spiritual existence.)

This is the eighth verse of the Śata-nāma-stotra of Lord Rāmacandra, which is found in the Padma Purāṇa. (Chaitanya-Charitamrita Madhya 9.29- AC BhaktivedantaSrilaPrabhupada)

In an era where the echoes of ancient dharma clash with disruptive modernity, Lord Rama’s anadi (unending) ethos is not just a beacon of enduring values, but as a sponge, a reflection and a mirror reflecting the diverse, often conflicting interpretations and aspirations shaping and driving contemporary Indian society and the world.

Standing tall in the vivid tapestry of Bharatiya ethos, Bhagavan Shri Rama stands as the ideal ‘Maryada Purushottama’, a harmonious amalgamation of adhyatmik depth and martial valour, embodying the ideal man as envisioned in Indian society, literature, music and song.

As elucidated by Shatavadhani R Ganesh in his book on the Kshatriya spirit, Rama exemplifies the profound concept of ‘Brahma-Kshattra’, where the transcendental pursuit of spiritual goals and the righteous wielding of weapons that amalgamate in the noble mission of protecting dharma, resonating with the eternal principle of ‘Dharmo Rakshati Rakshitah’ – the protected dharma, in turn, protects.”

The modern fallacy that India is a confederacy of ethno-linguistic nation states like Europe is an outcome of flawed historiography and a Eurocentric way of looking at the world. This has unfortunately been internalised by modern Indians without much opposition, questioning or reflection. Dr. Koenraad Elst opines that this country is a civilisation-state. According to him, nationalism with its connotation of homogenisation cannot do justice to India’s profound pluralism and respect for differences.

t is important to acknowledge the role of the classical epics in underlining Bharat’s cultural unity and propagating a value system that has served as a bulwark against hostile forces that have been forever inimical and destructive. They morph into asuras like Raktabija, spawning an incessant cycle of darkness. A profound positive force is needed to stand against this doomsday machine. India, as is often mentioned, is an old civilisation but a young country or nation state.

Our erudite first Prime Minister, in his speech on Indian independence day talked about a tryst with destiny and a soul of a nation long suppressed finding utterance. However, rooted as our bureaucracy and polity has been in European and non-Indic ways of looking at the world, traditional knowledge systems have been neglected, derided and ridiculed. Macaulay’s minions are indifferent to their own subversion.

For example, A.K. Ramanujan’s essay “Three Hundred Ramayanas: Five Examples and Three Thoughts on Translation” has been a subject of considerable debate and scholarly discourse.

His essay is commendable for highlighting the vast and diverse cultural landscape of the Ramayana tradition. He brings to light the myriad versions and narratives of the Ramayana that exist across different regions and communities in India and Southeast Asia.

Ramanujan also talks about the fascinating Jain narrative of the Ramayana, rationalising the Rama legend, making him a pacifist Baladeva and the arch-nemesis Ravana as a more human future tirthankara. Lakshmana kills Ravana in the Jain version of events. This aspect of the essay is crucial in understanding the Ramayana not just as a singular narrative but as a complex tapestry of stories that have evolved and adapted over time. Despite the contrary narratives, we can see how deep Lord Rama is ingrained in the very heart and soul of Bharat’s soil.

However, Ramanujan’s approach in categorizing these narratives underplays the centrality and sanctity of Maharishi Valmiki’s Ramayana in the core Indian tradition. The conflation and reinterpretation of local, often independent retellings with the spiritual and philosophical depth of the original epic could be seen as a methodological or deliberate oversight.

Ramanujan’s underlying assumptions regarding the creation and transmission of the Ramayana can easily be critiqued and repudiated. While he acknowledges the diversity of the narrative, there is a sense in his essay of treating these versions as independent of the cultural and spiritual ethos from which the Ramayana originates. Indic scholars often argue that such an approach overlooks the underlying unity of the Ramayana tradition across its various renditions.

In contrast, the works of famed Kannada littérateur S.L. Bhyrappa and M.P. Sahitya Akademi awardee actor-writer Ashutosh Rana based on the Ramayana, particularly focusing on ‘Uttara Kanda’ and ‘Ramrajya’ respectively, provide a compelling perspective on the epic, balancing a nuanced critique with an underlying respect for the sanctity and divinity of Lord Rama in the Sanatana world view.

This approach is reflective of a deeply rooted Indic tradition of intellectual inquiry, where revered figures and narratives are often examined through a humanistic lens, yet their spiritual and cultural significance remains unchallenged. Disrespect is commonplace in the modern milieu, where in the words of the Welsh poet W.H Davies, we have no time to stand and stare. Introspection and deep reflection are lacking in today’s time-bound, rough and tumble environment.

First, I consider Mr. Santeshivara Lingannaiah Bhyrappa’s Kannada novel ‘Uttara Kanda’ (2012) translated into English by Rashmi Terdal (2020).

Bhyrappa’s work is an exploration of the ‘Uttara Kanda’, the last section of the Ramayana, often considered the most controversial part of the Valmiki epic. His narrative delves into the complex moral and ethical dilemmas faced by Rama, particularly in the context of his treatment of Sita. This medium-sized translation, small by Bhyrappa standards, is reflective of his style, wherein he strips every last vestige of even divine characters, giving them a rare empathy and air of tragedy.

While Bhyrappa does not shy away from critiquing Rama’s actions, reading this book the reader can feel that his portrayal is not intended to diminish Rama’s divinity or the reverence millions of Indians have had for millennia

Instead, it humanizes Rama, making him more relatable and his dilemmas more poignant. This approach underscores the Indic tradition of ‘Naravatlila’, viewing divine figures in their human manifestations and understanding the profound lessons embedded in their lives. Why do the gods take human incarnations, suffering as the rest of humanity does in the cycle of samsara? They serve as an exemplar for the people to grapple with the existential problems of existence.

Bhyrappa’s narrative is an attempt to grapple with the intricate layers and unique pathos of dharma (righteousness) and the choices made by Rama, thereby offering readers an opportunity to reflect deeply on the ethical dimensions of these ancient stories.

In his comparatively recent work ‘Ramrajya’, Ashutosh Rana takes a somewhat similar but divergent approach. While exploring the concept and idea of ‘Ramrajya’ (the rule of Rama), often idealized as a time of perfect justice and harmony, Rana delves into the human aspects of Rama’s character and governance.

His work is a subtle critique of Rama’s decisions and actions, but it does so within a framework of deep reverence for Rama. Arguably less iconoclastic than Mr. Bhyrappa, Rana’s portrayal through the eyes of varied characters in the epic is aimed at understanding Rama’s principles of governance and leadership, and how they resonate with contemporary societal and political ideals.

Both Rana and Bhyrappa approach Rama’s story not to diminish its spiritual essence but to explore its relevance and applicability to modern times, reflecting a longstanding tradition in Indic scholarship, literature and popular culture of reinterpreting sacred narratives to align with contemporary contexts. However, this has recently degenerated into vile contempt and crassness.

The works of S.L. Bhyrappa and Ashutosh Rana represent a unique facet of Indic literary tradition where sacred narratives are subject to introspection and analysis, yet their spiritual core is upheld.

Their writings on the Ramayana reflect a deep engagement with the text, offering interpretations that are both intellectually stimulating, thought provoking and respectful of the epic’s enduring spiritual legacy. This approach reaffirms the versatility and timelessness of the Ramayana, demonstrating its capacity to inspire thoughtful discourse across ages and cultures.

When we travel across the length and the breadth of the Indian subcontinent, like both these authors we get an inkling of its soul and the connection to Bhagavan Rama. Something great men like Adi Shankara, Gandhi, Tagore and countless other sensitive spirits felt with the inner core of their beings. The 1983 Sanskrit movie on Shankara by G.V Iyer with its haunting refrain of ‘Aaakashampatitatamtoyam, sagarampratigacchati’ and the supposed final words of Mahatma Gandhi ‘Hey Ram’ are the connection of the sea with the source.

The tapestry of contemporary Bharatiya consciousness is intricately woven with the rich and diverse threads of millennia-spanning thoughts, discourses, and dialectics.

History and the lately derided word ‘mythology’ is, according to me, a window into the truth, a subjective portal of consciousness where Shri Rama enters our hearts, blessing the world with the munificence of his presence.

The vibrant intellectual mosaic, ranging from the poetic eloquence and genius of Bhasa to Bhavabhuti, the nuanced and varied narratives of Jain and Buddhist Ramayanas to the wise and sagacious insights of Samarth Ramdas who inspired Chattrapati Shivaji Maharaj, has been further enriched by the Persian translations commissioned by Mughal emperors.

In the crucible of India’s freedom struggle, luminaries like Gandhi, Tagore, Aurobindo, C Rajagopalachari, and Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan drew inspiration from Rama’s enduring spirit.

The distilled essence of Rama’s values catalysed profound intellectual ferment and churning, shaping the very bedrock of Bharatiya ideation and identity. This according to me is not hyperbole or an overstatement, Rama has permeated deeply into the subconscious mind of every person who has lived in the Indian subcontinent, the Indosphere and beyond.

The majestic aura of Prabhu Shri Rama, epitomizing both unyielding moral rectitude and formidable martial valor, has cast a profound influence across the annals of Indic history, inspiring monarchs from the venerable Gupta Empire to the valorous Gahadavalas and the illustrious Paramaras and the Vijayanagara kingdom, according to passionate writers and historians like Shri Venkatesh Rangan.

This legacy resonated powerfully with Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, after whose indomitable leadership and establishment the Maratha Empire expanded its might across Bharat from Attock to Cuttack, embodying Rama’s principles of righteousness and a just spirit of warriorship.

A legitimate question posed by critics is whether this just and inclusive approach also has been an Achilles’ heel or a self-defeating prophecy for Sanatana Civilisation and culture. We do not need to wallow in self-pity but do an objective analysis of our past. A clichéd saying, oft-repeated is that those who do not learn from history are condemned to repeat it.

India’s Dharmic righteousness is in marked contrast to the rest of the world. Dr. Meenakshi Jain contrasts the Spanish Reconquista of the Iberian peninsula to the 500 year battle for reclaiming the Rama Janmabhoomi.

When Spain and Portugal were liberated from Moor Arab influence, every cathedral converted into a mosque by the Arabs was reconverted to a Christian place of worship.

In contrast, despite overwhelming proof the Hindus have patiently struggled for half a millennium to get back one of the most sacred and revered place in Sanatana belief.

From Kashmir, the land of Saraswati and once the fountainhead of Indic scholarship to Kanyakumari in the South, countless temples and symbols of faith and learning were deliberately desecrated and destroyed. Yet, our famed and legendary tolerance and respect have led to piecemeal reconstruction at best.

Reflecting the perceptive observations of Dr. Meenakshi Jain and Sir V.S. Naipaul, India emerges as a civilization bearing the scars of its tumultuous history, still navigating the labyrinth towards rejuvenation and reawakening.

Its rich, unparalleled tapestry, having endured relentless upheavals, now grapples with a paradox where the erosion of its intrinsic identity and the shadow of ignorance have been, perplexingly, elevated to ideals.

This narrative not only challenges us to confront these aspirational anomalies but also to rekindle the profound wisdom and resilience that lie at the core of ancient and contemporary Bharat.

No account of Lord Rama’s ethos can be complete without a description of its interaction with other faiths.

Muhammad Iqbal, a prominent philosopher, poet, and politician in British India, had a profound respect for many figures in Indian history and Puranic narratives, including Lord Rama.

Iqbal, in his poetry, referred to Rama as ‘Imam-e-Hind’, which roughly translates to the ‘Spiritual Leader of India’. This reference is significant as it reflects Iqbal’s recognition of Rama not just as a legendary or religious figure, but as a symbol of moral and ethical values that transcend religious boundaries.

In his famous poem “Ram,” Iqbal wrote:

है राम के वजूद पे हिंदुस्तान को नाज़

अहल-ए-नज़र समझते हैं इस को इमाम-ए-हिंद

(hai rāma ke vajūda pe hiṃdustāna ko nāja

ahala-e-najara samajhate haiṃ isa ko imāma-e-hiṃda)

(India is proud of the existence of Ram,

The insightful consider him the Imam of India)

This verse illustrates how Iqbal, though a Muslim poet, acknowledged, admired and celebrated the cultural and spiritual significance of Lord Rama in the collective consciousness of India. He viewed Rama as a unifying figure, embodying the ethical and spiritual heritage of the country, beyond the confines of any single religion, ideology and way of looking at the world.

Iqbal’s portrayal of Rama as a leader and a guide for the nation is indicative of the syncretic cultural environment of the time, where mutual respect and admiration often transcended religious differences. This was needed then and is even more critical and relevant now.

This perspective is particularly noteworthy considering Iqbal’s own role as a profound Islamic thinker and philosopher who later played a significant part in the formation of modern-day Pakistan. His reverence for Rama signifies the shared cultural roots of the Indian subcontinent and underscores the inclusive nature of its heritage.

Lord Rama and Sikhism

The Punjab or the Vedic ‘Panca-Nada’ region is where according to many historians, the Vedic texts were created. The Sikh faith forged and emerged in the burning crucible of the Punjab has since its inception exemplars of the renunciate warrior traditions of ancient Bharat.

Lord, Thou takest Khurasan under Thy wing,

but yielded India to the invader’s wrath.

Yet thou takest no blame;

And sendest the Mughal as the messenger of death.

When there was such suffering, killing,

such shrieking in pain,

Didst not Thou, O God, feel pity?

Guru Nanak, Babar Vani

Verses penned by the first Sikh Guru on the impact of Babur’s invasion on the Punjab and India. Guru Nanak is also reported to have visited the Ram Janmabhoomi temple in 1511 CE. Guru Gobind Singh, the founder of the martial Khalsa is also mentioned as visiting the desecrated remains along with his mother when he was 7 years old. Dr. Kapil Kapoor describes Gobind Singh ji as the perfect example of the scholar-warrior. In this sense, he is like Bhagavan Rama, a moral heroic figure.

In the complex mosaic of Indian religious history, few groups capture the imagination quite like the Nihang Sikhs. The brave warriors, guardians of the faith, stand as steadfast sentinels of righteousness, where spiritual depth meets the warrior’s resolve.

In line with the mystical poet founder of the Sikh faith Nanak’s vision, Sikhism expanded into an activist but compassionate religion in line inspired by the ancient Sanatana ideals of Seva and Karuna for all sentient beings.

The demolition of the ancient Rama Janmasthan temple in 1528 CE by Mir Baqi was a cataclysmic event for all adherents of the Dharmic faiths in Bharat. As per an early 20th century text by Maulvi Abdul Ghaffar, when Babur in disguise visited the Avadh region for a fact finding mission, the Sufis Shah Jalal and Sayyid Musa Ashiqan urged him to destroy the Ayodhya Janmasthan temple in exchange for their blessings.

Islamist invasions and desecration were so commonplace that a concerted effort to reclaim the sacred place only started centuries later. In November 1858, Nihang Baba Fakir Singh Khalsa stormed into the Masjid Janamsthan (Babri Masjid) as a band of 25 Nihang Sikhs stood guard outside. He erected a symbol of Sri Bhagwan Rama inside the mosque and wrote ‘Ram Ram’ on the walls with charcoal.

When the Supreme Court ordered the formation of a trust to construct a temple for Lord Ram in the longstanding dispute over the religious site on November 9, 2019, it even cited the event from 1858.

The Nihang Sikhs, an intriguing and distinctive order within Sikhism, are renowned for their unwavering adherence to the martial traditions established by the Sikh Gurus.

The original Panj Pyaras or five first converts to the Sikh fold, were Hindus of all castes and drawn from every region of Akhand Bharat.

According to the Guru tradition, the Khalsa is the lotus flower and the Hindus are the roots of the tradition. The Nihang are considered to be as close to the Miri-Piri (temporal and spiritual authority) and the Sikh Rehat Maryada (guidelines for living) as preached by the original Gurus as possible. The Sikh panthic worldview exhorts people to take up the Khalsa path and become a karma yogi or a proactive renunciate, quite like Shri Rama himself.

In line with the Sikh tradition’s respect for the one formless divine again largely inspired by Advaita belief, they respect Hindu deities such as Bhagavan Shri Rama and Shri Krishna. Their traditions of KarSeva that were inspired by Sanatana practices in turn inspired the Ram Janmabhoomi movement and karsevaks in the 1990s. Modern India needs to counter alienation, flawed narratives and the general misinformation that is alienating a core Dharmic path away from the spirit of Shri Rama.

Lord Rama, Buddhism and the Tremendous Impact on South East Asia

Lord Rama’s transcendent stature, extending far beyond the boundaries of traditional Hinduism into the spiritual tapestry of Buddhism, casts a resplendent glow across the cultural landscape of Southeast Asia. In the Buddhist tradition, Rama is revered not as a deity, but as an exemplar of moral rectitude and noble virtues. India’s cultural soft power, so widespread in ancient times has taken a backseat to China. I explore in some detail how Rama is depicted and how India can use this ancient narrative to reconnect with South East Asia, traditionally the Indosphere.

His epic narrative, while differing in details and emphasis, resonates profoundly in countries such as Thailand, where ‘Ramakien’ – the Thai adaptation of the Ramayana – is woven into the very fabric of national identity, imbuing the arts, theatre, and literature with its timeless themes.

The figures of Ramkhamhaeng, PhraRamarat along with the historical city of Ayutthaya, are significant elements in the cultural and historical landscape of Thailand, each with a unique connection to the Ramayana and Thai history.

PhraRamarat:

The term ‘PhraRamarat’ in Thailand can be seen as a reference to the ideal of kingship as embodied by Lord Rama, the ‘Rama Rajya’ of classical Bharat, as per Shri Venkatesh Rangan and other scholars. In Thai culture, where Hindu and Buddhist traditions intertwine, Rama is revered as a model ruler, with his virtues often idealized in the concept of kingship. PhraRamarat, then, symbolizes a ruler who embodies the principles of dharma (righteousness) and justice, much like Rama of the Ramayana.

Ayutthaya was the capital of the Kingdom of Siam (Thailand) from 1350 to 1767. The city, named after Ayodhya, the birthplace of Lord Rama in the Ramayana, was one of the world’s largest urban areas at the time and a center of global diplomacy and commerce.

The naming of Ayutthaya signifies the deep-rooted cultural and religious connections between Thailand and Indian civilization. The city, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is an archaeological masterpiece.

In Cambodia, the ‘Reamker’ mirrors this impact, where Rama’s tale of righteousness and valor is deeply embedded in the country’s cultural and religious heritage, influencing everything from classical dance to temple architecture.

The Philippines, Vietnam, Mongolia and Indonesia too have their unique renditions of the Ramayana, exemplified by Indonesia’s ‘Kakawin Ramayana’, which infuses Hindu narrative and tremendous Sanskrit scholarship with local genius, philosophical insights, and the enchanting shadow puppetry of ‘Wayang Kulit’.

Thus, Lord Rama’s story, majestic and multidimensional, transcends religious confines, radiating as a beacon of ethical and spiritual guidance across Southeast Asia, testament to the shared human quest for virtue and wisdom. But Indians are sadly unaware of this great heritage and influence. Practically, with growing economic might, we can connect

Contemporary Challenges

Independent India riddled with a Nehruvian ecosystem and vote bank politics assiduously denied the majority community their rights and a claim to their temples.

Bogged down by false historiography and increased fault lines sown and nurtured by the people in power including Dravidian politics, caste divisions, separatism in Punjab, Kashmir and the North East, the legendary interdependence and amity between all Indic faiths deteriorated.

It is critical for our sustained existence to ensure that elitist distortion and division does not act like an insidious termite and ensure unity and prosperity.

In the realm of intellectual discourse on cultural and philosophical paradigms, Rajiv Malhotra’s concept of ‘Western universalism’ presents a compelling contrast to the Indic understanding of the world, deeply rooted in its own Dharmic frameworks.

Malhotra, in his reflective works, posits that Western universalism often subsumes diverse cultural narratives under a homogenized, often Eurocentric worldview. This perspective, he argues, overlooks the rich tapestry of pluralistic and contextual wisdom inherent in Indic traditions, where figures like Lord Rama not only symbolize moral and spiritual ideals but also embody the complexity and diversity of Bharatiya Dharma.

In contrast, the Indic or Dharmic worldview, enriched by narratives such as the Ramayana, emphasizes ‘Svadharma’ – the idea that truth and duty are contextual and individualized, rejecting one-size-fits-all solutions. This philosophy acknowledges the multiplicity of paths to the divine and the varied expressions of truth, reflecting a more inclusive and holistic understanding of the world.

Aravindan Neelakandan, a ‘Swarajya’ editor, in his insightful book, offers a sympathetic yet critical examination of what he terms ‘Cargo Cult Hindutva’, and emphasizes the need for a more nuanced approach in understanding and promoting Sanatana Dharma.

He critiques the oversimplified adoption of Hindu symbols and narratives – often stripped of their deeper philosophical meanings – solely for political or cultural identity assertion.

Neelakandan advocates for a comprehensive plan for the future of Sanatana Dharma, one that not only withstands the challenges of a volatile global landscape but also stays true to the complex, introspective, and inherently diverse nature of Dharmic traditions.

This approach calls for a deeper engagement with the philosophical and spiritual depths of Sanatana Dharma, moving beyond superficial appropriations. It involves embracing the pluralism and profound wisdom embedded in Dharmic practices and texts, and applying these principles to address contemporary global issues.

In this vision, the teachings of Lord Rama and other Dharmic figures are not just relics of the past but living guides that offer insights into ethics, governance, environmental stewardship, and the pursuit of personal and collective well-being in an increasingly complex world.

Another interesting perspective is of Professor S.N. Balagangadhara in his seminal works such as ‘The Heathen in his Blindness: Asia, the West and the Dynamic of Religion.’ His exploration raises an important point on how colonial interpretations have significantly influenced Indian self-understanding, leading to a skewed perception of their own cultural and religious practices.

Many other scholars including him have delved into the Euro centric construct of secularism and the Western view of religion, highlighting the discrepancies when these ideas are applied to the Indian context.

As we navigate the multifaceted landscape of the 21st century, the ethos of Lord Rama stands not merely as a beacon from the past but as a dynamic guide for the future, illuminating a path through the confluence of tradition and modernity. Our approach can be a playground for research, curiosity and speculation not a battlefield between diametrically opposing sides.

In contemporary Indian society, Rama’s values – his unwavering commitment to dharma, his profound sense of duty, and his embodiment of moral rectitude – resonate with increasing relevance amidst the complexities of modern life. These values, while rooted in ancient wisdom, offer insightful solutions to contemporary challenges, advocating for a balance between ethical integrity and pragmatic realism.

However, as we embrace Rama’s ideals, we also encounter the need for a nuanced interpretation that aligns with today’s diverse and pluralistic world which often has skewed trajectories.

Rama’s story, when understood in its depth and breadth, provides a framework for building a society that upholds righteousness and justice, while celebrating diversity and inclusivity.

As we forge ahead, it is imperative to adopt a comprehensive approach to understanding and applying Rama’s teachings. Keeping in line with the ancient Indic concept of ‘manthan’, there are definitely going to be many more disruptions and volatile dynamic equilibriums.

The future involves traversing these minefields and integrating Prabhu Rama’s timeless wisdom with contemporary thought, ensuring that his ethos informs our actions and decisions, both at personal and societal levels.

The path ahead calls for an educational and cultural renaissance that revives the profound lessons from Rama’s life, ensuring that they are not lost in translation but are instead reinvigorated to guide, inspire, and enlighten future generations.

In conclusion, Lord Rama’s ethos, when viewed through a lens that is reverential and rational, historical and contemporary, offers a rich tapestry of values for the 21st century. It beckons us to embark on a journey of moral awakening and societal transformation, driven by the timeless principles of dharma and a deep sense of duty and engagement with the world.

Feature Image Credit: gnttv.com

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.