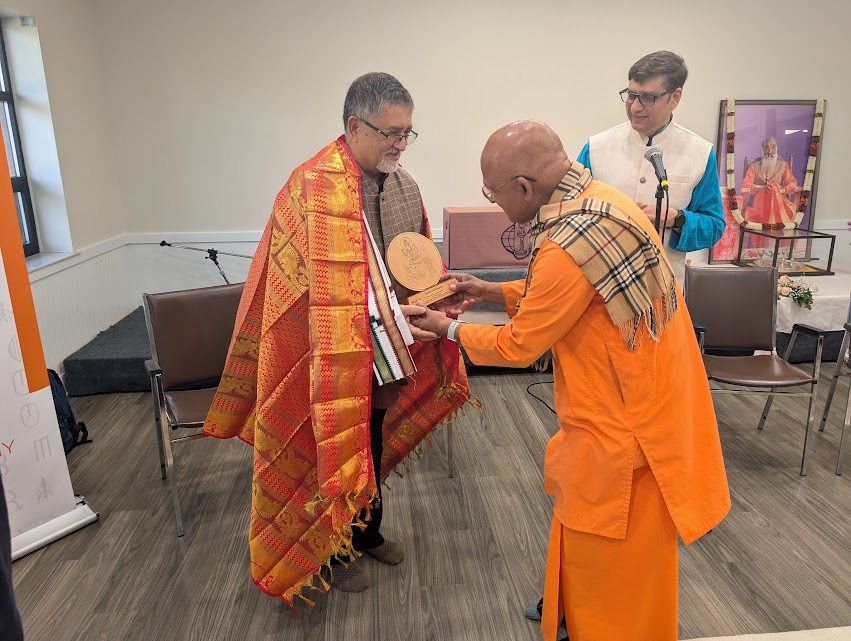

(On September 6, 2025, INDICA USA hosted the Grateful2Gurus (G2G) ceremony at the Chinmaya Abhyudaya Retreat Center, Chicago, where Prof. Ramesh Rao was felicitated for his four decades of teaching, scholarship, and contributions to dharmic discourse. The event was graced by Pujya Swami Sharanananda Ji of Chinmaya Mission Chicago and the Honorable Consul General S mnath Ghosh. In his acceptance remarks, Prof. Rao spoke on the ethics of speech in the Indian tradition and its place in dharmic thought. The following article draws from that address…)

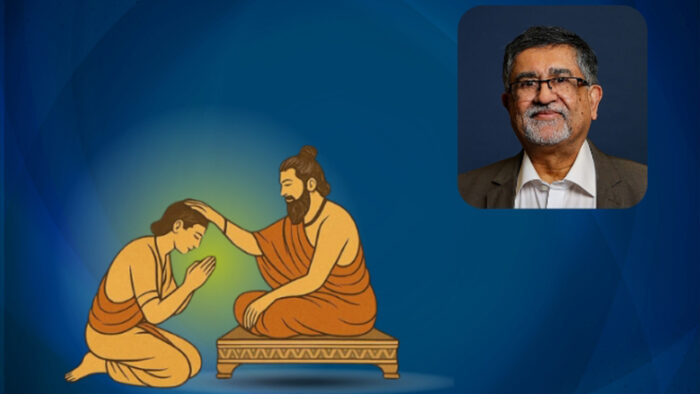

(Figure 1: Prof. Ramesh Rao felicitated by Swami Sharanananda Ji at Chicago’s #Grateful2Gurus 2025)

Pujya Swamiji, the Honorable Consul General Somnath Ghosh, beloved guests, friends, fellow dharmic travelers, and curious young seekers…

A good talk begins with a story, I am told ☺

I arrived in the US exactly 40 years ago (I came to Hattiesburg, MS, on September 5, 1985). About three months later, I took a Trailways bus to Chicago and stayed with my cousin and her lovely young family for almost a week. She is here today in the audience. I had but a thin jacket then, not knowing anything more about winters in the US than the mild first few weeks of cool weather in Hattiesburg, but I was able to bear the brunt of the cold Chicago winds wearing that flimsy grey jacket that had a hood. I was young and clueless. The sharp, cold winds that blew through the canyons between tall buildings in downtown Chicago left me very, very cold!

The two-week journey I made that first Christmas break on a $100 go anywhere ticket brought me to Chicago first, then took me to Wausau, Wisconsin, where I had another cousin, and then all the way to Salt Lake City, where I had a friend with whom I had gone to graduate school in Mysore.

I am here 40 years later with a PhD and almost 40 years of teaching experience across four states. I have a few books to my credit. I will be retiring next year. End of story.

Did INDICA USA take pity on that hapless student of 40 years ago to confer this honor today? ☺

I am not an expert or trained in Indian philosophy or Sanskrit. I am not even a historian. At best, I consider myself an adhyaapaka or upaadhyaaya, and to some extent an aacharya (an instructor/teacher /professional of communication studies). I cannot, with any impartiality, claim to be a guru (a guide and counselor) though I have guided a few graduate students’ theses and professional projects, and I have counseled younger colleagues on courses of action to take or not take in their careers. Surely, I am not a Dhrishta (a visionary who has inspired new ways of thinking, though some in the audience will tell you that I was one of the few who stuck his neck out and wrote about the bias against Hindus and Hinduism in American media and American higher education). So, you have to bear with me today, and if nothing else, maybe what I will share briefly about Indian speech ethics will inspire some youngsters in the audience to pursue higher studies in the traditions of Indian speech and ethics.

I also have a confession to make. I did not come to the US to pursue studies in the field of communication. By the way, my PhD thesis is on hostage negotiations. You see, I was a copy editor for “The Hindu” in 1985 when I decided to pack my bags and come to the US. I thought I would get a master’s degree in journalism and return home to pursue my journalism career. But the Gods and fate have different plans. That I am being honored today in this beautiful setting is something that I had not imagined when I arrived here with my two worn suitcases and $500 in American Express travelers’ checks 40 years ago.

I have taught a course in public speaking for the past four decades, and ethics is one of the chapters in all of those speech textbooks. We tell students not to lie, not to exaggerate, and not to plagiarize. We offer students the usual examples of leaders appealing to the base passions of their listeners, and the Hitler and Goebbels example is usually invoked. Surely, these are basic principles that guide people in their public and private transactions anywhere in the world, right? So, what can be special about Indian speech traditions and ethics? Before I get into some details, one thing I would like to highlight is that all rules in Indian speech traditions are under the framework of “DHARMA” in the pursuit of Rta – the cosmic order, and the universal law that governs the universe.

I have written a chapter on speech ethics for a book on the Natyashastra. Let me draw from it to tell you a little bit about what I know of Indian speech ethics.

Indian Ethics

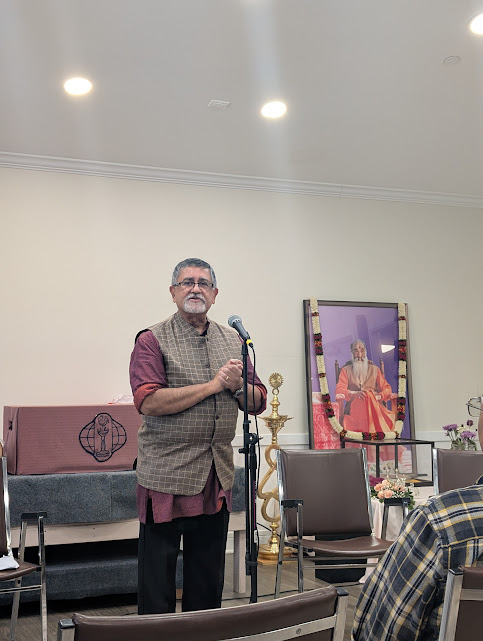

(Figure 2: Dr. Ramesh Rao shares insights on Indian speech ethics)

Truthfulness was the “foremost standard” for speech in India. The exhortation to speak the truth is contained in many Indian texts, not just for speaking some transcendent truths, but also for the advice that was given to individuals. Dharma demanded that people follow the rules laid out for them.

Ethics, or neetishaastra, is the study of “right or good conduct” (Mahadevan, 1991, p. 52). When I want to do something that results in an action, it is called conduct (Mahadevan, p. 53). Our willingness to do something is based on our character or nature, and our character is determined by our actions. What motivates our actions? Ethicists are concerned with motivation, and it is motivation that is judged or evaluated in measuring the consequences of action. Here, we have to ask, “How much free will do we have”? In Sanātana Dharma, karma offers us an explanation for the individual’s nature and therefore of his or her will to do things or to avoid action. “Karma stands for the freedom of man’s will,” says Mahadevan (p. 55), and karma “does not bind man entirely” (p. 57). So, how do we judge action then? Mahadevan contends that Indian thinkers were keenly aware of the shortcomings of a merely juristic view of right and wrong and therefore tied moral action to a “scheme of human ends – purushārthas (p. 63) – artha (wealth), kāma (pleasure), dharma (righteousness), and moksha (freedom). The first two merely serve to direct human beings toward the higher goals – righteousness and liberation.

Similarly, in a chapter on “Ethics in Ancient India” (Bussanich, 2010), we are reminded that the “… widely accepted doctrine of karma… suffused ethical theories of all Indian schools, including those of Buddhists and Jains. The impact of the law of karma, with its stress on just desserts, on Indian ethical thought cannot be exaggerated.” This is theodicy – the vindication of divine goodness/God. Max Weber considered the concept of karma “the most consistent theodicy ever produced” (p. 36).

A quick aside. Does dharma comprise one general set of rules for ethical behavior for all people? Let us think about it. Also, is there an equivalent to the Western idea of “ethics” in ancient Indian terminology/philosophy? Scholars have drawn parallels between Manu’s observation that “What a man seeks to know with all his heart and is not ashamed to perform, at which his inner being rejoices – that is the mark of Goodness (sattva-guna)” with Immanuel Kant’s claim that “people feel self-contentment, which is distinct from their happiness, when they do their duty for its own sake, not for their own satisfaction” (p. 38). This is interesting, but let us not judge. Let us take desha and kaala into account and consider what might have led to these formulations.

Another scholar draws our attention to Platonic ethics and how Indian thinkers relied and drew upon the law of karma “to connect non-moral facts and moral goods, the metaphysical and normative” (p. 41). He also draws a comparison between the Indian varna system and Plato’s account of justice that was based on the division of the Athenian citizenry into three classes – “guardians/philosophers, auxiliaries/warriors, and producers” in which slaves did not make up a distinct class. Just like in the Manusmriti and in the Bhagavad Gita, where the higher varnas are prescribed certain behaviors, similarly Socrates argued that “the top two classes should have distinct virtues and that the lowest has none” (Bossanich, p. 43).

Another scholar summarizes the “Western” quest to find universal principles for human behavior, and argues that the quest reflects Western assumptions that “the general is to be preferred to the particular,” as “the specific and the contextual imply a capricious narrowness of thought that is potentially volatile and cannot be relied upon to achieve the best conduct in all humans” (p. 348). In ancient Indian thought, the approach to life is diverse, and therefore “Hindu literature as a whole rarely provides a straightforward answer to any question” (p. 350). The Western quest, projected as a “philosophical” inquiry into the universal, is a rather suspect mission because “personhood itself is complex and contested” (Dhand, p. 351), and this “particularity of human beings is a fact that is not only acknowledged, but is… formally built into Hindu classifications of action” (p. 351).

Let’s say, at this point, that the ancient Indian approach to moral and ethical speech and actions is at once both pragmatic as well as bound by the quest for “ego effacement” and considering the world as a family, and the individual working for the welfare of the family.

Others have said that in Indian thought, the basis of morality is self-sacrifice (tyaaga, yagna are aspects of “self-sacrifice”). What does this mean? Without controlling the senses, and therefore limiting our desires, or the pursuit of sensual pleasure, our focus will be on satisfying ourselves and paying little or no attention to social obligations. Without social obligations, what is the role or significance of morality or ethics? Therefore, controlling one’s desires is the foundation for ethical behavior. The control of senses (indrīyanigraha), non-attraction toward objects (anāsakti), control of desires (nishkāmata), and purity of mind (chittashuddhi) are essential if one is to truly practice love, compassion, forgiveness, and friendship (Tiwari, p. xviii). Why do we have to give up the pursuit of pleasure and be obligated to society? Because the final aim of an individual, in our belief system, is the attainment of moksha (liberation from the cycle of birth and death). Self-sacrifice, therefore, is the root of social virtues in Hindu philosophy, and without individual morality, there cannot be social morality.

From where did we get the rules and injunctions about what constitutes ethical behavior? Primarily, these rules and precepts are included in the dharma shastras. The pursuit of dharma – virtues and duties — is the kernel of morality. The two important types of dharma relevant in the life of an individual are the sādharana dharma and the varnāshrama dharma. The former offers a set of rules and precepts applicable to all individuals, simply because of their human status, and because it is only human beings who are both privileged and bound by rules that they consciously follow. It is only human beings who are given choices: not just to act or not act but to act or not act in different ways and in different contexts based not just on the desire to mate, eat, and go to sleep but to consider their own well-being and their quest to control their desires as well as to be “good citizens” – to act in favor of their fellow beings – support cosmic order.

Speech Ethics

The truthfulness standard applies both to public discourse and to interpersonal communication. Speaking truthfully was necessary to cultivate modesty and humility in the speaker, and to assure social harmony and consensus in society. This belief in speaking the truth was what influenced Gandhi’s choice, in the twentieth century, of pursuing satyāgraha (“holding to truth”), some have argued.

Giving examples of the influence of holding to truthfulness as a standard, an author mentions the highly repetitive style of discourse in ancient Indian texts, in which repetition played the part of stressing the claim to truth on the listeners. Repetition is part of the universal force – with the earth revolving round and round the sun, the moon around the earth, and seasons appearing in the same sequence repeatedly. The concepts of reincarnation and time as cyclical are also powerful shapers of the Indian worldview.

In India, the act of repeating (japa) a mantra (a holy syllable or hymn) and its calming and transforming effects has been known for a long time, and it is no surprise, therefore, that ancient Indian texts incorporate careful and stylistic repetition. Repetition is also an act of affirmation and of the confidence the speaker has in what she is conveying. The metaphor of truth-telling having magical physical effects is used in the Mahābhārata, for example. Truth-telling is described as a “performance of reality” rather than just a description of reality. By chanting the Vedas accurately, with the right intonation, at the right speed, and at the appropriate time, the student came to “realize” the full meaning of sacred sounds. The act of uttering the truth was considered liberating, though it was not, however, just speaking any ordinary truth that liberated a human being: it was uttering the sacred truths contained in mantras requiring long years of study and discipline that gave power to the person to “endorse” transcendent truth.

The power of truth-telling, not just in a “religious circumstance,” but everywhere else, has the possible “therapeutic effects”. If so, can truth be told unequivocally in all situations by all kinds of people? Also, what other standards of speech, other than truthfulness, were offered by Indian philosophers, and how do those standards support or undermine truth-telling?

Identification of “truthfulness as a standard” can be traced to the Dharmashāstras. Pakshilaswamin Vatsyāyana of the Nyaya School (not to be confused with the well-known Vatsyayana of the Kama Sutra fame) analyzed righteous and unrighteous conduct that can be associated with one’s body, mind, and speech. Vices connected with speech included mithya (uttering falsehood), parusha (caustic talk), sūchanā (slander/calumny), and asambaddha (absurd talk). Virtues connected with speech included satya (veracity or truthfulness), hita vāchana (talking with good intention), priya vāchana (gentle talk), and svādhyāya (recitation of scriptures). As we can see, there were other standards, beyond truthfulness, that the commentators identified as right and wrong conduct.

The Dharmasūtras are an expansive compendium of rules of conduct concerning all aspects of an individual’s life, and while we can make connections to speech and truth under many headings, let us focus on those sutras (aphorisms) that are directly related to speech and truth, including anger, harsh speech, slander/calumny, speech, and truth. There are many, many allusions to all these, and to make sure that I don’t burden you with a laundry list of these, let me offer you a few:

- An initiated student shall not be given to anger

- Faults that torment a man include anger; refraining from anger, a man attains all

- Cultured people are those who are free from anger

- A man who has been consecrated for a sacrifice should not become angry

- If someone uses harsh words against a person against whom one is not permitted to use such words, he should eat food without milk, spices, or salt for three days

- A student who has completed Vedic studies should refrain from speaking harshly about either the gods or the king

- If someone uses abusive words, he shall practice austerities for a maximum of three days

- An innocent person rubs his sin off on the man who slanders him

- When someone engages in slander… he should bathe reciting the Ablinga or Vārunē formulas, or other purificatory texts in proportion to the frequency with which he has committed these offences

- Giving false evidence, slanderous statements that will reach the king’s ear, and false accusations against an elder are equal to sins, causing loss of status

- A man should control his breath several times in accordance with the rules given in authoritative texts for sins committed through his… speech…

Manu and Manusmriti have taken a beating for a while now, but there are new commentaries on the Manusmriti that should offer us context and meaning as well as rules for conducting our lives well. This aphorism in the Manusmriti should therefore be of interest to us: “when telling the truth will result in the execution of a Shūdra, Vaishya, Kshatriya, or a Brāhmana, a man may tell a lie… for that is far better than the truth” (8.104). Manu is therefore arguing for carefully considering the context in which one might either blurt out or tell the truth, leading to immediate violence.

Speech ethics in the Mahabharata and the Ramayana

In the Mahābhārata, we find that speech/vāni enables us to understand order and truth, and that speech is central in all relationships, and that “the ordering of language is an essential part of the language of order”. We find reference in the Mahābhārata too of desha and kāla, as coordinates of history, that influences all relationships, but that all individuals, while bound by time and place constraints, should seek to transcend that historical limitation because it is a “spiritual necessity” and not just because of ethical imperatives. What is the contribution of the Mahābhārata to our understanding of the human condition? That the “language of experience” (concrete reality) and the “language of transcendence” (abstract idea) are woven together, and that if they are separated, it would lead to “untruth” – anrta – and to violence.

In the Shāntiparva of the Mahābhārata (158.8-10), it is said that greed leads to “forceful speech,” “self-praise,” “falsehood and lies”. Speech has certain causes, emanates because of certain psychological conditions, and therefore, we must understand those conditions so that speech becomes automatically regulated rather than merely contrived.

In the Udyoga-parva (34.78-80), it is remarked that hurtful and dry words affect the hearer in many ways. “They are like arrows that burn the bones and the heart and the life of their victim, who day and night is pained by them. The wise man should therefore give up hurtful speech.”

The Anushāsana-parva (104.33) offers another powerful metaphor about hurtful speech: “The trees pierced by arrows or cut by the axe grow again, but the dreadful wound by nasty words does not ever heal,” and in the same parva (104.34) it is said that the ”ear-shaped arrow, or the spear, or the arrow made of iron, can still be removed from the body, but it is impossible to remove the arrow of hurting words, for it gets embedded in the heart.”

Even Lord Krishna, speaking to Nārada, complains about his relatives, whom he accuses of using hurtful words: “But their bitter words hurt me deeply and keep burning my heart” (Shanti-parva, 162.8-9). Among the thirty-six self-disciplines that Bhīshma propounds for a king (in the Shanti-parva), the fifth says “speak pleasingly without being pitiable,” the fourteenth says, “do not indulge in self-praise,” and the thirty-second says, “be kind, but without being sarcastic”. This advice and keen observations about speech are not time-bound and get to the core of appropriate and relevant speech.

Coming to the Ramayana, describing life in Ayodhya, an author notes that people were “lofty souled and possessed of good conduct,” that they “shunned greed, falsehood, dishonesty,” and none of them were “nihilists”. Thus, nihilistic speech, which asserts that existence is without objective meaning, purpose, or intrinsic value, is itself unethical.

In conclusion, as one author observes, “Hinduism does have embedded in its social psychology a universal ethics whose primary frame of reference is worldly, and not otherworldly salvation. This can become the basis for social activism. This universal ethic, however, relies upon relational metaphors – dharma and rta — rather than an ideology of individualism. While exerting oneself broadly for the whole, one’s conduct yet always remains relational and contextual”. Thus, we can conclude, with Vātsyayana, that we better avoid the vices connected with speech — mithya (uttering falsehood), parusha (caustic talk), sūchanā (slander), and asambaddha (absurd talk) – and pursue the telling of truth, satya, speaking with good intention (hita vāchana), speaking gently (priya vāchana), and reciting the scriptures (svādhyāya) so that we acquire the discipline and steadfastness to act ethically and speak with care, keeping in mind the situational context.

We live in the age of Artificial Intelligence, unnecessary and excessive consumption, unbridled competition, and greed. We don’t know who is working on what, whose voice has been faked, whose image has been morphed, and whose words are attributed to whom. But we should not despair. It is in such times that we should recall our foundational values and make it our duty to act and speak in a manner that upholds universal law, the natural order, and cosmic truth. Let us not allow ourselves to be affected by the constant buzz of news and views. We should learn to silence them. Let us be patient and speak gently. Let us offer words of support to those who are in pain. Let us recite our sacred texts.

I would like to thank once again all of the wonderful people at INDICA US for this honor, offer my namaskars to Pujya Swamiji, my salutations to the Honorable Consul General, and thanks to all of you for your generosity and your time.

Om, Harihi Om!

(Figure 3: INDICA USA team and well-wishers at Grateful2Gurus 2025, Chicago)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.