In the Krta Yuga, the way was Jñāna,

in the Treta, it was Karma,

in the Dvāpara, it was both Jñāna and Karma,

but in Kali, it is Yoga that gives joy and freedom.

~ T. Krishnamacharya, Yogañjalisāram, Verse 28

It was a time long before colourful Yoga mats, fashionable stretch pants and swanky gyms. Apollo 11 had not yet landed on the moon, nor was there any television to cover such events. A young engineer, visiting his home in Chennai, was seated on the verandah with his father, a traditional brahmin, clad in a white dhoti. Suddenly, a large car drove up the narrow street and out jumped a middle-aged lady in a brightly coloured dress. She ran up to the brahmin, threw her arms around him in a big hug, and shouted, “Thank you, Professor! Thank you so much!”

To see a woman from New Zealand embracing an elderly brahmin would have been quite shocking for his son. (Remember it was Chennai of the 60s). Yet, the old man simply smiled and treated her graciously. “She suffered from insomnia,” he said to his son later. “She could barely sleep even with powerful drugs. She’s been studying (Yoga) with me and is finally getting her first nights of good sleep in more than twenty years!”

East had met with the West and the young man had experienced, in a rather dramatic way, the tremendous healing power of Yoga, where western medicine had failed. Inspired by this encounter, the young man, T.K.V. Desikachar, would go on to become one of the most influential teachers of Yoga in our era. While his father, none other than T. Krishnamacharya, is often referred to as “the father of modern Yoga”.

However, it was not for the first time that such an encounter between East and West had occurred. It was but one in a long series, which marked the global spread of this ancient science of Yoga far beyond Bharat’s shores. References to Yogis are found as far back as in the Greek classical sources. Perhaps one of the most fascinating meeting, between a world conqueror and these conquerors of the inner world, was Alexander’s encounter with Indian ascetics. In the seventh century AD, a Chinese pilgrim and disciple of Xuanzang, reported how popular Sānkhya, a philosophy closely allied to Yoga, was in the country. Later, through the translation of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras by the famous Arab historian and scientist Al Biruni (AD 973-1050), Yoga made its way as far as Istanbul.

But perhaps the most defining moment for Yoga in the modern world came when Swami Vivekananda traveled to the West. His address at the Parliament of World Religions in 1893 is an event which every patriotic Indian recounts with pride. Lecturing extensively, both during this first visit (1893-97) and his second visit (1899-1902), Swami Vivekananda gave western audiences a glimpse of “Raja Yoga” for the first time.

The spark had been lit! Suddenly, the modern world began to evince a tremendous interest in the ancient science. By 1920, a young Paramahamsa Yogananda, founder of the Yogoda Satsang Society, moved to the United States, bringing Yoga to an entire continent through his lectures. Today, he is perhaps one of the most easily recognizable faces when one thinks of the word Yogi! Swami Sivananda (1887–1963), a trained doctor, founded the Yoga-Vedanta Forest Academy and authored over 200 books on Yoga. His disciple Satchidananda founded the Integral Yoga Institute in 1966, which today has numerous centers globally. While Yoga was thus making rapid inroads into the Western World, India itself was not left behind. The Kaivalyadhama Health and Yoga Research Center came up in Lonavala, Maharashtra, as early as 1924, thanks to the efforts of Swami Kuvalayananda. Today, Kaivalyadham is one of the premier Yoga institutions in India, providing several formal certificate courses in Yoga and promoting research in Yoga. No survey of the development of Yoga in the modern world would be complete without a mention of BKS Iyengar (1918–2014), named one of the 100 most influential people in the world by Time Magazine.

The spark had been lit! Suddenly, the modern world began to evince a tremendous interest in the ancient science. By 1920, a young Paramahamsa Yogananda, founder of the Yogoda Satsang Society, moved to the United States, bringing Yoga to an entire continent through his lectures. Today, he is perhaps one of the most easily recognizable faces when one thinks of the word Yogi! Swami Sivananda (1887–1963), a trained doctor, founded the Yoga-Vedanta Forest Academy and authored over 200 books on Yoga. His disciple Satchidananda founded the Integral Yoga Institute in 1966, which today has numerous centers globally. While Yoga was thus making rapid inroads into the Western World, India itself was not left behind. The Kaivalyadhama Health and Yoga Research Center came up in Lonavala, Maharashtra, as early as 1924, thanks to the efforts of Swami Kuvalayananda. Today, Kaivalyadham is one of the premier Yoga institutions in India, providing several formal certificate courses in Yoga and promoting research in Yoga. No survey of the development of Yoga in the modern world would be complete without a mention of BKS Iyengar (1918–2014), named one of the 100 most influential people in the world by Time Magazine.

This tremendous proliferation of Yoga in the modern world was far from homogenous. Each of the influential teachers of Yoga in the modern world had significant differences in their approach and emphasis. Thus, we all carry with us a certain perception of what Yoga is. To some, it is a purely health and fitness oriented activity; some approach it through various breathing techniques (made immensely popular by contemporary Yoga Gurus); still others discover Yoga through meditation.

Some of us may practice none of these, yet, Yoga is deeply engrained in our spiritual literature. The rise of organizations like the Ramakrishna Mission and Chinmaya Mission led to the emergence of fresh perspectives on the ancient paths of Bhakti Yoga, Karma Yoga and Jnana Yoga and their relevance to modern life. Bal Gangadhar Tilak, the leading light of the Indian freedom struggle, reexamined the core message the Gita through the lens of Karma Yoga, i.e., the heroic performance of one’s duty and skill in action as Yoga which leads to salvation.

While all these diverse perspectives and approaches to Yoga are no doubt enriching, emphasizing any one at the expense of the other could lead to an incomplete picture of what Yoga really is. Thus, to holistically understand and appreciate the relevance of Yoga in the modern world, it is necessary to look at how Yoga was defined in its foundational texts. Now, Yoga’s earliest origins lie in the Vedic period and there are several unmistakable references to Yoga in the early Upanishads. But the problem then and today was/is one of synthesis.

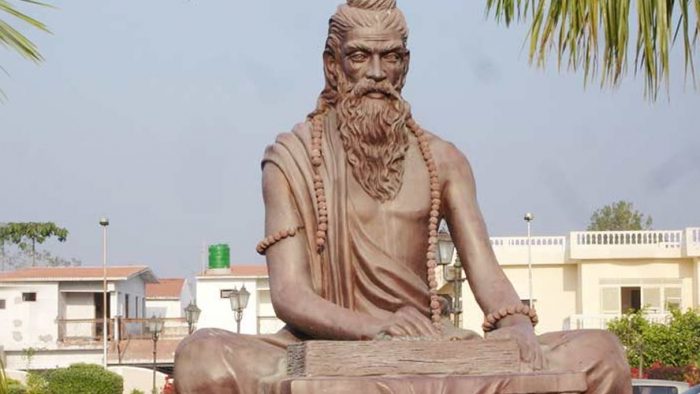

That synthesis finally came in the post Vedic era thanks to a remarkable sage and teacher, Patanjali. We cannot say with certainty when Patanjali lived but tradition remembers him as an ancient teacher who gave us Yoga to purify the mind, Ayurveda to heal the body, and Grammar to purify speech. Patanjali compiled the scattered doctrines of Yoga from centuries earlier into 195 succinct aphorisms (or Sutras) expressed in crisp yet beautiful language. A Sutra is said to have the attributes of being precise, coherent, unambiguous, universal, condensing many thoughts and based on irrefutable sources of knowledge. Patanjali’s work was so remarkable in its clarity of presentation, its thoroughness of scope and systematic treatment that it went on to establish Yoga as one of the six systems of Indic philosophy, alongside Sānkhya, Nyāya, Vaisheshika, Mīmāmsa and Vedānta.

Ever since, numerous ancient, medieval and modern scholars have written numerous commentaries elucidating the Yoga Sutras. These included some of the greatest intellectuals of India – like Vyasa, Vachaspati Mishra, Adi Shankara, Bhoja Raja, the scholar-king, Vijnanabhiksu and Swami Vivekananda, closer to our time. Numerous other works on Yoga too were written like the Yoga Yajnavalkya, the Gheranda Samhita, the Shiva Samhita, the Yoga Rahasya etc. But when it comes to the foundations of Yoga, it is Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras which are the ultimate authentic source for scholars and laymen alike.

Thus, it is to Patanjali we must turn when we ask the fundamental question: “What is Yoga?” But just for a moment let us look at where the word Yoga comes from. The word Yoga is derived from the root “Yuj” – “to bring two things together, to meet, to unite”. The great modern-day Yoga teacher TKV Desikachar further explained it as “to tie the strands of the mind together”. This word root beautifully leads us on to Patanjali’s definition in the second Sutra of his first chapter:

Thus, it is to Patanjali we must turn when we ask the fundamental question: “What is Yoga?” But just for a moment let us look at where the word Yoga comes from. The word Yoga is derived from the root “Yuj” – “to bring two things together, to meet, to unite”. The great modern-day Yoga teacher TKV Desikachar further explained it as “to tie the strands of the mind together”. This word root beautifully leads us on to Patanjali’s definition in the second Sutra of his first chapter:

“Yogas citta vritti nirodah”

Yoga is the stilling of the changing states of the mind. [I.1]

Patanjali then devotes the rest of the chapter to discussing how to control these vṛttis or fluctuating states of the mind through the practice of dispassion, non-attachment and faith. He also discusses at length factors such as idleness, doubt, dejection, sloth, carelessness, inability to sustain a goal etc, which hinder our progress towards this goal of Yoga. He offers a wide range of aids such as cultivating maitrī (friendship), karunā (compassion), equanimity and dispassion, as also control of the breath and practicing meditation as means to overcome these distractions.

That said, first chapter, still presupposes a certain degree of steadiness of the mind. Its focus is largely on the goal of attaining Samādhi. But the fact is most beginners to Yoga practice don’t care about Samādhi and need solutions for their restless, distracted mind. It is precisely for this reason that Patanjali now introduces us to Sādhana Pāda, or the “Practice Chapter” for the beginner whose mind is yet untrained. Sādhana or practice is anything that takes one towards the achievement of a goal (or Siddhi).

Transforming the mind from a distracted state to one of attention is clearly not a one step process or overnight task. In the Āṣṭāṅga Yoga system, it is a holistic journey, encompassing morality, self-discipline, restraint, physical aspects like Asana practice and breath control, and finally inward practices such as meditation.

But, if all of this were thrown at the beginner in one go, he/she would very likely be overwhelmed. Here’s where Patanjali shows his genius as a teacher. He introduces to us to only a small dose called “Kriya Yoga” in the first sutra of the second chapter:

tapaḥ-svādhyāya-īśvarapraṇidhānāni kriyā yogaḥ

Kriya Yoga, the path of action, consists of self-discipline, self-study, and surrender to the Lord. [II.1]

There is, of course, lot more to Yoga than this. But this baby step is exactly what a beginner needs to get started on a life transforming journey of Āṣṭāṅga Yoga. Just as is easier to do something for 5 minutes a day instead of 1 hour a day, it is easier to approach Yoga with a compact definition at first before expanding it to all aspects of one’s life.

In course the rest of the 2nd Chapter, Patanjali discusses at length the causes of human afflictions, arising from ignorance, ego, excessive attachments, unreasonable dislikes, and insecurity. A lot of our misery is self-inflicted and stems from our limited sense of self-identification. “I am no good” or “I am inferior”, “I am weak”, “I am fat”, “I am dark”, “I am not good looking”, “I am not rich” – as we go through life, we construct our identity around such false identifications. In the Yoga philosophy, the mind and the body are simply instruments allowing awareness to perceive the world. They experience states which are ever-changing. Whereas, the true Self is unchanging. Patanjali says that imagining the mind and body to be the real Self is Ego (“Asmita”). Likewise, hankering excessively for the temporal and missing the eternal is ignorance (Avidyā). Both these inevitably lead to pain.

Apart from ignorance, ego, hate etc, there are lot more negative emotions one could be trapped in – such as jealousy. As a general solution, Patanjali offers a good tip called Pratipaksha-bhavanam or, deliberately cultivating opposite/counteracting thoughts:

Vitarka-bādhane pratipaksha bhavanam

Upon being harassed by negative thoughts, one should cultivate counteracting thoughts [II.33]

But ultimately, for the solution to work, it has to be holistic – acting at all levels of one’s being. Thus, after a lengthy interlude of Sānkhya theory, Patanjali finally in the 29th Sutra gets to the practical part which most of us modern practitioners of Yoga would be interested in, viz., Āṣṭāṅga Yoga:

yama-niyamāsana-prāṇāyāma-pratyāhāra-dhāraṇā-dhyāna-samādhayo ‘ṣṭāv aṅgāni

The eight limbs of Yoga are abstentions, observances, posture, breath control, disengagement of the senses, concentration, meditation, and absorption. [II.29]

Now, given that there are 8 limbs, a question may arise as to where should one begin: Should we always begin at the physical level? TKV Desikachar answers:

“There are many ways of practicing Yoga, and gradually the interest in one path may lead to another. So, it could be by studying the Yoga Sutras or by meditating. Or we may instead begin with practicing Asanas and so start to understand Yoga through the experience of the body. We can also begin with Pranāyāma, feeling the breath as the movement of our inner being. There are no prescriptions regarding where and how our practice should begin… We begin where we are and how we are, and whatever happens, happens…”

“There are many ways of practicing Yoga, and gradually the interest in one path may lead to another. So, it could be by studying the Yoga Sutras or by meditating. Or we may instead begin with practicing Asanas and so start to understand Yoga through the experience of the body. We can also begin with Pranāyāma, feeling the breath as the movement of our inner being. There are no prescriptions regarding where and how our practice should begin… We begin where we are and how we are, and whatever happens, happens…”

We could begin with an area which interests us the most. But ultimately, just as a wheel cannot roll down the road, unless it round, we cannot progress too far on the path of Yoga without becoming aware of the holistic nature of our being and realizing that we are made of body, breath, mind, and more. Thus, it’s no use being an expert at all possible Asanas without knowing the inner goals of Yoga or being an expert at Sānkhya theory without being able to sit still even for a few minutes.

But none of this would even make sense without character, morality, and personal integrity. Patanjali emphasizes all aspects of human life. And perhaps that is why the very first two limbs of Yoga which he mentions are the Yamas and Niyamas. He also goes on to say in Sutra II.31 that these are universal values and unconditioned by place or time or birth; adhering to them is a great a vow (mahāvratam). Patanjali was also an expert at human nature. He perhaps knew well that merely saying that these are a great vow wouldn’t quite motivate us to follow them. So, for each Yama and Niyama Patanjali also suggests a corresponding reward, which makes it all worth it.

While Patanjali’s description of the Yamas is a great start, many people, especially youth and adolescents may need much more detailed guidance. What are the real non-negotiable corner-stones of character even in the rat race or the world with all its temptations? In the context of Yoga in the modern world, the contribution of the Kauai Hindu Monastery in Hawaii must be highlighted in this regard. Gurudeva Sivaya Subramuniyaswami began looking for ancient texts which could expand upon the Yamas and Niyamas listed by Patanjali. He finally discovered the answer in a 2000 year old Tamil classic, the Thirumantiram. The Thirumantiram is primarily a work on Shaiva Siddantha, but it also discusses Ashtanga Yoga extensively. Using this, he and his team at the Kauai Monastery put together “Yoga’s Forgotten Foundation” – a work that offers guidelines of good character and self-discipline to prepare one to lead a wholesome life of Yoga.

Why do I stress this so much? Perhaps it is worth remembering that as remarkable as the global spread of Yoga has been, sadly, it is also a field which rocked by numerous scandals. Oftentimes, those who were once considered excellent teachers, have been carried away and tainted for life. Needless to say, the psychological trauma resulting from all this to students has been immense. The interaction between East and West has not been without its share of problems. At the extreme end of the spectrum lie incidents like the Salmonella bioterror attack of 1984 in the The Dalles, Oregon, executed by the followers of a famous teacher who had in his career lectured on subjects like Vijnana Bhairava – a definitive work on meditation techniques. It is a grim reminder that no one is above the Yamas and Niyamas and practicing Yoga without them is a sure shot recipe for disaster.

While all these early founding fathers of Yoga in the modern world emphasized its philosophical doctrines and meditative practices, in the modern world, Yoga has somehow become synonymous with Asanas. For most of us, the first thing which comes to our mind when we think of Yoga is complex postures. The cover of any popular book on Yoga we pick off the shelf is likely to feature a most perfect and enviable bend or stretch. And, when the health conscious among us, take a morning stroll through the neighbourhood park, the most visible form of Yoga we see in action is Asana.

Asanas themselves have always been an integral limb of Yoga – right from its earliest texts. A question which often gets asked is: While Patanjali lists Asana as a limb of Ashtanga Yoga, why doesn’t he name any specific Asanas. The answer probably lies in the fact that in the ancient Guru Parampara system, the practical aspects of Yoga practice were imparted to the student as direct instruction. Nevertheless, in sage Tirumular’s very ancient work, the Thirumantiram, possibly dating back over 2000 years, we find mention of several popular Asanas. The fascinating thing is all these are performed to this day by Yoga practitioners!

The Hatha Yoga system, founded by Matsyendranath of the Nath Sampradaya, gained popularity in the medieval period thanks to Svatmarama, who wrote the Hatha Pradipika. It is here that we first begin to see a systematic description of Yoga Asanas. The Hatha Pradipika describes 15 Asanas, 8 of which are not seated postures. Thus, while there was always an emphasis on Asanas by Yogis as means to prepare the body and mind to achieve higher meditative states, Asana as the visible face of Yoga is still a very modern phenomenon.

In the context of modern Yoga, the contribution of BKS Iyengar is unparalleled in this regard. Iyengar’s lifetime of work contributed greatly to helping seekers realize

- The universality of Yoga’s core principles,

- The profound impact of Yoga on health,

- Giving Yoga a definitive modern form, which practitioners irrespective of their background to relate to and practice.

Whether or not one follows BKS Iyengar’s school of Yoga, whether or not one performs rigorous headstand, Shirasasana, or amazing twists and bends of Uttanasana and Dhanurasana is immaterial here. But thanks to his work, one thing is for sure – If you want to do Yoga, get your mat out and get on the mat now!

Moving from the physical to the mental plane, the later part of the 20th century has certainly witnessed a renewed interest in the emerging “science of the mind”. Meditative practices have always been a legacy common to both Yoga and Buddhism. But how they manage to work has typically been considered to fall in the realm of the mystic and esoteric. This has led scientific minds to wonder – do they work? And if they do, what really is their scientific basis? Two remarkable scientific developments towards the end of the 20th century have finally given us a very tangible proof of the effectiveness of practices like meditation and Yoga:

- fMRI (Functional magnetic resonance imaging)

- Neuroplasticity

It is known that when an area of the brain is in use, blood flow to that region increases. fMRI has given us the means to detect subtle increases in blood flow to areas of the brain with higher metabolic activity. These areas of increased metabolic activity indicate which regions of the brain are in use to process stimuli. Now, recent studies have indeed shown heightened activity in areas such as the frontal cortex & prefrontal cortex, during various forms of meditation such as Zen, Vipassana etc.

These findings are exciting because they indicate the possibility of greater voluntary control over attention through meditation techniques. Apart from attentiveness, fMRI results from practitioners of techniques like “compassion meditation” also indicated heightened activity in brain regions like the amygdala – implying a greater sensitivity to emotional expression and positive emotion due to the neural circuitry activated.

Another exciting discovery observed in Neuroimaging studies using fMRI is actual changes to brain traits and physical structure. The previously held scientific view was that the brain develops mainly during a critical period in early childhood and then remains relatively static.

However, fMRI studies on meditators found several regions of the brain to be consistently altered, including areas which are key to meta-awareness, memory consolidation, self and emotion regulation. These changes were distinguished by increases in density of grey matter regions in the brains of individuals who meditate in versus individuals who do not.

There is also evidence to suggest meditation plays a protective role against the natural reduction in grey matter volume associated with aging. Long-term meditation practitioners have also shown to have a higher tolerance for pain.

These changes have proved that the notion of a static or unchanged brain is not true and that several aspects of the brain can be altered even into adulthood and throughout an individual’s life. This is referred to as Neuroplasticity.

While many of us may be hesitant to subject our spiritual practices, which have very deep personal meaning, to the scrutiny of science, these studies have actually given us excellent proof – if proof were needed – of their effectiveness. Changes to the physical structure of the brain resulting from meditation hold the long-term solution to many issues ranging from anxiety, depression, addiction, fear, and anger, and ultimately the ability of the body to heal itself.

We thus stand at an exciting point in human history where modern science has begun to validate the deep efficacy of Yoga which our ancients intuitively knew so well. What’s more, the United Nations recent declaration of an International Day of Yoga is symbolic of Yoga’s global reach today and its ability to transform millions of lives, across continents, religions, languages and creeds. The efforts of the Government of day must also be heartily welcomed – this is, after all, this is our heritage. Moreover, what should have been done years ago has finally been done. And it’s always heartening to see a Prime Minister who tweets about Yoga Asanas, amid all the mug slinging in Indian politics!

But come International Yoga Day, June 21 , we will once again witness the perennial squabbles on Twitter – “Is Yoga religious?”, with one camp all too eager to strip it of its religious roots and insist that it is only a “technology” and the other camp hurling choice words of indignation at them. As we have done through the course of this essay, it’s perhaps best to ask what Patanjali himself says on the matter.

There is no doubt that Patanjali included a conception of Ishvara, a personal God, in his system. That said, it must also be noted that several points in Patanjali’s system are based on the system of the Sankhyā and the points of difference are very few. Sankhyā only admits a nearly perfected, being temporarily in charge of a cycle. Yoga holds the mind to be equally all-pervading with the soul, or Purusha, but Sankhyā does not. To Patanjali, the goal of Yoga could be attained by devotion to Ishvara. Patanjali describes Ishvara as a special soul, untouched by afflictions (kleshas) or the fructification of Karma

kleśa-karma-vipākāśayair aparāmṛṣṭaḥ puruṣa-viśeṣa Īśvaraḥ

The Lord is a special soul. He is untouched by the obstacles [to the practice of yoga], karma, the fructification [of karma], and subconscious predispositions. [I.24]

To Patanjali, Ishvara was also the first teacher.

pūrveṣām api guruḥ kālenānavacchedāt

Īśvara was also the teacher of the ancients, because he is not limited by Time. [I.26]

And he recommends the worship of Ishvara with the primal sound Om. [It is well known that many Yogic practices, such as Pranayama were “Samantraka” or accompanied with the recitation of Mantras].

tasya vācakaḥ praṇavaḥ

The name designating him is the mystical syllable oṁ. [I.27]

While Patanjali recommends devotion to Ishvara to aspiring Yogis, no where do we find a sectarian tone or a dogmatic, exclusive tone creeping into the Sutras. His is a broad and universal vision, which should be acceptable to people of diverse religious backgrounds and sensitivities. Ideally, none should feel alienated or uncomfortable at the thought of practicing Yoga. As commentator Edwin Bryant observes: “That millions of people worldwide continue to find his text personally relevant today speaks to his foresight in this regard.”

One of the great modern teachers of Yoga, Tirumalai Krishnamacharya summed it up well in his poem Yoganjalisaram:

tava vā mama vā sadānusaraṇāt

namanānmananāt prasanna cittaḥ

bhagavān vāñchitamakhilam datvā

kinte bhūyaḥ priyamiti hasati

Your Lord or mine, it does not matter.

What matters is: Meditate with humility.

The Lord, pleased, gives what you seek

and happily will give more.

~ T. Krishnamacharya, Yogañjalisāram, Verse 28

Finally, given the role of religiousness in Yoga, questions could arise on its basis vis-à-vis the nature of truth in the exact sciences. A scientist does not tell you to believe in anything. He gathers observations and documents results from experiments. Scientific theories appeal to our sense of reason inasmuch that they are the best possible explanations which account for all the available data. So, we can at once see the truth or fallacy of the conclusions. There is no place for dogma.

Sadly, much of how religion is passed down is based purely upon faith and belief. But we can’t possibly talk about the efficacy religious experience until we have felt it. Here is where Yoga, being absolutely based on praxis, offers great hope. As with science, Yoga too does not demand blind acceptance of anything. The science of Yoga gives us the means of observing for ourselves the internal states, and the instrument is the mind itself. It thus opens for us the doors to that universal experience of the ultimate reality, which is basis for all religion. That is an experience which is open to all of us and waiting to be felt through constant practice.

* * *

References:

- Health, Healing and Beyond: Yoga and Living Tradition of T. Krishnamacharya – T.K.V. Desikachar, with R.H. Cravens, North Point Press.

- Roots of Yoga, James Mallinson and Mark Singleton, Penguin Books.

- The Yoga Sūtras of Patañjali: A New Edition, Translation and Commentary – Edwin F Bryant, North Point Press

- Pātañjala Yoga Sūtra – Dr. PV. Karambelkar, Kaivalyadham Publications

- Religiousness in Yoga: Lectures on Theory and Practice, T.K.V. Desikachar, University Press of America

- Yogavārttika of Vijñābhikṣu, Vol. II (Sādhanapāda) – Rukmani, T.S.

- The Heart of Yoga: Developing a Personal Practice – TKV Desikachar

- Light on the Yoga Sūtras of Patañjali – BKS Iyengar

- Rāja Yoga – Swami Vivekananda

- The Illustrated Light on Yoga, BKS Iyengar, Harper Collins Publishers, India

- Hatha Yoga Pradipika, Swami Muktibodhananda, Yoga Publications Trust, Munger, Bihar.

(Note: This essay received an honourable mention as the results of the Essay Competition for Yogasutra Competition held by Indic Today for Indic Academy.)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.