In the earlier article, we looked at the intricacies involved in comprehending any Sanskrit work of literature. The works of great ṛṣis and kavis are inevitably multi-layered in terms of the meaning they espouse; and therefore just a superficial reading is likely to leave the reader only partially informed. Apart from various styles of composition (rīti) and various styles of narration (bheda), we had looked at the three modes of interpretation (bhāṣā) of these granthas. It would be a good exercise to recall these three modes before proceeding to look at some examples.

- Samādhi bhāṣā is that style of interpretation where the evident meaning of the words is accepted. In a sense it is the literal meaning of the composition. Delving into the deeper meaning of the material at hand is not warranted to get the samādhi bhāṣā tātparya.

- Darśana bhāṣā is that method of understanding where the philosophical meaning hidden in the material is sought. There are two high level approaches in this. When looking at a grantha that belongs to a particular sampradāya, the literal meaning of a given text could appear deviant. But using the lens of darśana bhāṣā, reconciliation is possible. A second category is when the text is analyzed with a spiritual or philosophical nuance and the deeper ādhi–daivika meaning is extracted.

- Guhya bhāṣā is when the text, upon deep inspection, reveals a hidden or mystical meaning. Here again, the bhāṣā could be of two types. The first one is when the message is indeed hidden but it need not be a mystical or esoteric one. The second category is when the meaning turns out to be truly metaphysical.

Since every śloka necessarily has a samādhi bhāṣā meaning (the evident meaning), let us look at a few examples of texts that contain samādhi and darśana interpretations.

The opening verse of the Raghuvaṁśam, a great mahākāvya by Kālidāsa, is as follows:

वागर्थाविव संपृक्तौ वागर्थप्रतिपत्तये । जगतः पितरौ वन्दे पार्वतीपरमेश्वरौ ॥

A simple translation of this śloka, using the samādhi bhāṣā, would be:

“In order to derive the pertinent meaning from the word, I bow to the parents of the world, Pārvatī and Parameśvara, who are inseparable just like the word and its meaning.”

Such an interpretation, of course, brings great joy and marks an auspicious beginning – maṅgala – for the work. It compares Parvati and Shiva to word and its meaning – a very appropriate analogy here given the context of the grantha.

However the śloka can be interpreted in a deeper way that could make it even more relevant. We use the darśana bhāṣā method to do so.

Pārvatī is eulogized as the abhimānī devatā of vāk – the presiding deity for words and Śiva is the abhimānī devatā of manas – the presiding deity of the mind, which shall comprehend the meaning. Kālidāsa, by simultaneously bowing down to Pārvatī and Śiva, is seeking their blessings so that the poem which he is to compose can be created with the right words that clearly express his intended creative meaning. Just as the divine duo is inseparably combined, the words and meanings shall always go together in his poetry. Similarly, the readers of this kāvya can gain the blessings of Pārvatī and Śiva so that the meaning of every śloka they read becomes clear in their mind as well.

Thus we see that the same śloka can be interpreted at two different (and progressively higher) planes.

Another good example of such a combination of samādhi and darśana bhāṣās can be seen in the Rukmiṇīśavijaya, a great poem by the 16th century saint poet Śrī Vādirāja Tīrtha. In the sixth canto of this poem, Śrī Vādirāja has composed a śloka describing the setting of the sun, in this way:

करैर्गिरीन्द्रान् परितो दधानोsप्यसौ विवस्वान् पतितः किलाब्दौ |

ममेत्थमाभाति सरिच्छरीरविशोषकं तत्पतिरग्रसीत्तम् ||

The samādhi bhāṣā style interpretation of this śloka says:

“Even though the Sun tried to hold on to the excellent mountain from all sides with his rays, he fell down. Seems to me that since he had pained the bodies of the rivers, (by drying them with his sharp rays) their lord, the ocean, swallowed him.”

A wonderful way of describing the sunset, no doubt. When we, however, put on the ādhyātmika lens, we can derive yet another meaning out of this śloka.

The sun in this śloka stands for a person who does para-pīḍana. He troubles others and causes them misery. He is doing so with the confidence that he has the support of the mighty, which in this case is the mountain. And yet, one day he falls. And this happens because the protector of the downtrodden (The Supreme Paramātmā) always comes to the rescue. Therefore, one must never trouble the weak falsely assuming power and support would last forever.

Let us now look at some verses with samādhi and guhya interpretations.

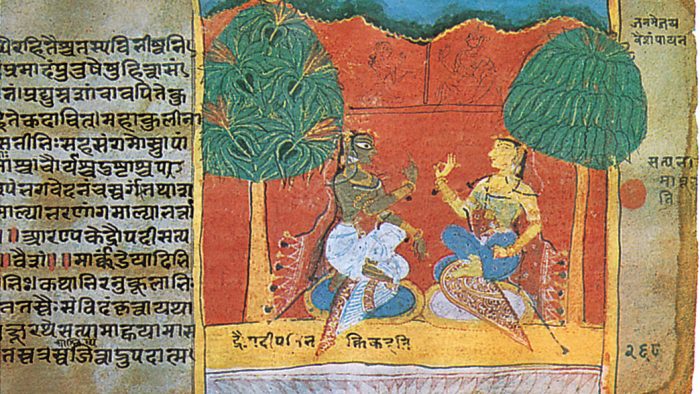

The Mahābhārata offers us many examples of ślokas that have a hidden meaning, considerably different from the apparent meaning. The most enlightening examples of such usage comes from the Ādiparva when the Pāṇḍavas are asked to go to Vāraṇāvata by Dhṛtarāṣṭra. The evil plan of the Kauravas is to make the five brothers stay in a Palace of Wax; and then burn them alive when a suitable opportunity arrives.

Just before heading out, the Pāṇḍavas take the blessings of all the elders in the family. Vidura, who has complete knowledge of the evil plan, advises the Pāṇḍavas in a few ślokas. The verses seem to convey abstract hitopadeśa (words of advise and comfort) when in reality they bear hidden meanings. Through these ślokas the entire plan of the Kauravas is conveyed by Vidura and he also advises them on the escape plan. Two examples will serve well here.

Vidura says to Yudhiṣṭhira:

कक्षघ्नः शिशिरघ्नश्च महाकक्षे बिलौकसः। न दहेदिति चात्मानं यो रक्षति स जीवति ॥ (Mahābhārata I.157.22)

“That which burns the forests and melts snow, cannot burn the ones who reside in burrows in that very forest. He who (understands this and) accordingly protects himself; survives.”

The guhya bhāṣā of this śloka is in fact a warning to the Pāṇḍavas. Vidura talks about the threat of fire. Fire can melt snow and burn mighty forests down. But, rodents and other animals staying in deep burrows in the very same burning forests are not harmed. One who understands that the invincible looking fire can be escaped by a similar behaviour; will survive that fire. Vidura basically instructs Pāṇḍavas to be wary of a fire, and to respond to the same by escaping from it through a burrow (and not trying to douse it).

Vidura further clarifies to Bhīmasena:

श्वाविच्छरणमासाद्य प्रमुच्येत हुताशनात् ।। (Mahābhārata I.157.24cd)

“Reach the home of the porcupine and be saved from fire.”

The guhya bhāṣā based interpretation of this śloka gives instructions on how to escape from the impending fire. The home of a porcupine is an underground tunnel that has two openings. When the fire errupts eventually, Pāṇḍavas must exit through the underground tunnel.

Ślokas such as these are many in our literature and make for fascinating reading, while at the same time increasing our understanding of the underlying intricacies.

Let us now look at some verses with samādhi, darśana and guhya interpretations

A third category of ślokas are those where the creative genius of the author is exceedingly high. A single śloka can have all three interpretations – samādhi, darśana and guhya. Let us look at one such example.

The ‘Tīrthaprabandha’ is a Sanskrit composition by Śrī Vādirāja Tīrtha composed in the 16th century. It is in effect a diary of the various Tīrthakṣetras visited by Śrī Vādirāja Tīrtha. At every kṣetra, he had composed a few ślokas in praise of the deity of the kṣetra or the auspicious river or mountain in the vicinity. More than a hundred of such sacred places were visited by Śrī Vādirāja Tīrtha and ślokas were composed.

While at Udupi (in Karnataka), he composed a wonderful śloka in praise of Śrī Kṛṣṇa, who is the main deity at the Śrī Kṛṣṇa Maṭha. The śloka is as below:

चाञ्चल्यं पृष्ठदेशे कठिणकृतिरधोवक्त्रता क्वापि कोपो

याञ्चा कस्मादपकृतिरूपकारिश्वापि प्राज्ञमौले ।

स्त्र्यर्थेsन्यस्त्रीश्ववज्ञा किमिति रमण ते चोरता मायिकत्वम्

चित्रं रोहावरोहाविति विरसगिराsप्यादृतः पातु कृष्णः॥ (Tīrthaprabandha 12)

The samādhi bhāṣā style of looking at this śloka tells us that this śloka praises Śrī Kṛṣṇa as if a gopikā from Vṛndāvana is eulogizing him. The translation would be:

“O Kṛṣṇa! One who is the crown jewel of the knowledgeable and one who gives joy (to them)! Why did you develop unsteadiness? Why did you behave differently behind the back? Why have you put down your face? Why do you beg without any reason? Why do you harm even those who are serving you? For the sake of one woman, why do you harm so many other women? Why do you have the habit of stealing? Your habit of causing good to some and bad to others is surprising! May Lord Kṛṣṇa, who in spite of such painful words is still the subject of great respect always protect us.”

It seems like the lament of an aggrieved gopikā who wants Śrī Kṛṣṇa to be with her always. She expresses the pain of Sri Krishna showing attention to other gopikās, being away from her, being indifferent to her and so on.

The same śloka turns into a fascinating prayer of the daśāvatāras of Lord Viṣṇu when it is analyzed with the darśana bhāṣā.

Śrī Vādirāja Tīrtha describes the Matsya avatāra when he asks why Sri Krishna was unsteady. The Matsya always moves around in the ocean.

The carrying of the Mandāra Mountain on the back as Kūrma avatāra is being referred to when Śrī Vādirāja Tīrtha says Sri Krishna behaves differently behind the back.

The putting down of the face refers to the Varāha avatāra and also refers to the anger of Viṣṇu in the Narasiṁha avatāra during the killing of Hiraṇyakaśipu.

The question about begging refers to the Vāmana avatāra.

The harm caused to those who serve Him refers to the killing of the Kṣatriyas in the Paraśurāma avatāra.

The harming of other women refers to the damage caused to Śūrpaṇakhā and other daitya women for Sītā in the Rāma avatāra.

The stealing alludes to the Kṛṣṇa avatāra. The causing of harm to some and good to others refers to the illusory preaching done in the Buddha avatāra and the killing of evil people and protection of sajjanas in the Kalki avatāra.

Thus the simple complaining of a desperate gopikā transforms into a powerful prayer of Lord Viṣṇu.

When we mull over this very śloka using the lens of guhya bhāṣā, yet another spiritual meaning becomes evident. Śrī Vādirāja Tīrtha indicates to us the way to obtain the feet of the Supreme Personality of Kṛṣṇa. In other words surrendering ourselves to Śrī Kṛṣṇa and constantly seeking his company will

- Remove the unsteadiness of our manas

- Put us irreversibly on the path of bhakti (no turning on our backs)

- Remove the ṣaḍripus such as krodha (anger)

- Make us go after jñāna (begging of knowledge)

- Destroy our enemies who come in the path of our sādhanā

- Prevent us from committing mahāpātakas such as parastrīsaṅga (lusting after other women), and steya (stealing)

- Bring us true knowledge by removing illusion

- And finally destroying our saṁsāra cakra (cycle of birth and death)

Thus the entire code of conduct for sadācāra (noble living) is revealed in this single śloka.

Conclusion

The meaning of the word saṁskṛta is ‘refined’. Sanskrit literature reflects our great culture, well refined over the course of thousands of years. Its essence becomes obvious only when it is studied and analyzed under the watchful eyes of devout adherents. Only when a practitioner undertakes the teaching of these fascinating granthas, does the true purport of each work come to the fore. Let us strive to keep our ancient traditions and customs alive, so we may forever continue to absorb the nectar they offer!

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.