Painting is perhaps the oldest form of art that has been with us since the Cro-Magnon man started making rock paintings. Some of the oldest are to be found in India too at Bhimbetka. In the classical era, we find rock murals in China, in Central Asia and paintings on pottery in ancient Greece. In India, there are rock paintings in many places in the south. The era matures with the illustrious age of the Thanjavur wall paintings which were done on walls of the Great Temple. In north India, many schools came into being, including Pahari, Kangra, and Rajasthani.

Apart from painting on a dedicated surface the art of painting actually found flavor in many other utilitarian arts. The various handloom centers all over India started weaving exquisite designs, patterns, and entire stories on to the handloom saris that they created. Thus were born the saree clusters of India. In the east, there was the Madhubani in Bihar, Baluchari in Bengal, and the Pattachitra in Odisha. In the west, there was Patola in Gujarat, Pochampally in Telangana. In the south, there was Kanjivaram in Tamil Nadu. Most of these sarees obviously meant for utility also sported dharmic themes like the scenes from the famous epics.

This aspect of art is also illuminating on another difference between traditional and modern art. In traditional societies, there was no strict division between ‘Art’ and ‘Utilitarian Objects’. Both came together in articles of daily use which were both beautiful and useful. That art should be seen as separate from usefulness was not a concept known to traditional societies.

They needed objects for daily use and had an eye for the aesthetic. Thus they made the objects of daily use attractive. In a traditional society there is no division between the worker and the artist, as Coomaraswamy says:

The thing to be made, then, is always something humanly useful. No rational being works for indefinite ends. If the artist makes a table, it is to put things on; if he makes an image, it is as a support for contemplation. There is no division of fine or useless from decorative and useful arts; the table is made to give intellectual pleasure as well as to support a weight, the image gives sensual, or as some prefer to call it, aesthetic pleasure at the same time that it provides support for contemplation. There is no caste division of the artist from the workman such as we are inured to in industrial societies… (Coomaraswamy 79-80)

DIVINE INSPIRATION VS. ARTISTIC INNOVATION

One thing which is common in all these schools is that the art piece is not signed. We know these paintings by the name of the schools in which they were made, but not by the name of the artist.

The artist is missing from these marvelous pieces of art. The ideal of the Indian artist was to conform to the rules laid down by the great masters and not to create something radically new. There were some differences owing to the local medium and idiom but the goal was to conform to the standards created by the jnanis and the rishis.

The canons of Hindu Iconography laid down in the various Agamas and the Puranas dictated the symbolism of diverse mudras (hand gestures) and ayudhas (weapons) and postures. This symbolism was not something that the artists themselves devised. This symbolism was not individual and not different in every case. This does not mean that the artist only had pre-set actions to follow. There was considerable freedom for the artist to choose the symbols that he wanted his piece to portray. There is much variety in Hindu sculpture all over India, but the artist seldom invented the symbols and meanings out of individual innovation.

There was no concept of individual artistic innovation. Instead, the Sanatana ethos had a concept of divine inspiration. It was believed that artists do not create something novel out of their own talent. Instead, a fresh interpretation of the Ultimate Truth dawns upon the artist as divine inspiration during meditation. These artists/ painters would meditate for hours while creating memorable works. It was only by meditating upon the object or the deity and by losing oneself in the object of meditation, by losing the agency of the artist itself, that the most acclaimed of art, the greatest of paintings were created.

THE BREAK IN THE RENAISSANCE

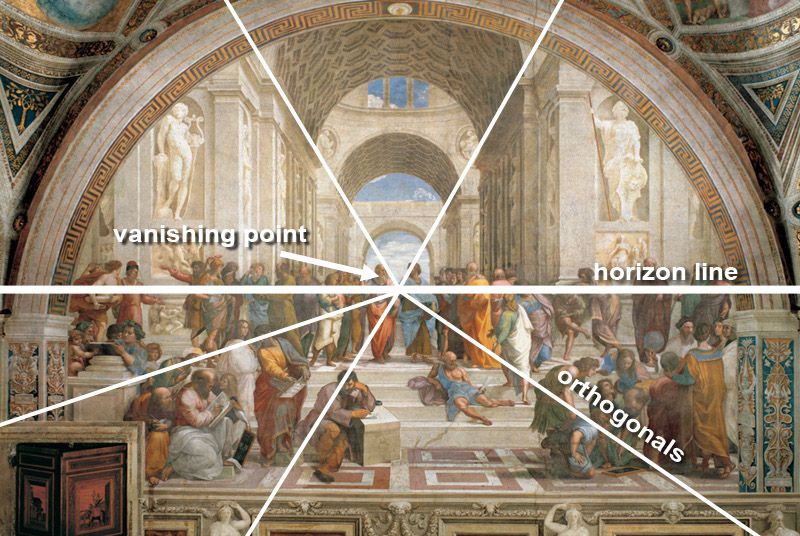

It was more or less the same in all ancient civilizations including ancient China, Japan, and Greece. It was only in the Renaissance that the painter starts featuring in the painting and for the first time, we have something peculiar: named art. For the first time, we can firmly attribute paintings to their masters. Thus we know that The Last Supper was the work of Da Vinci; The Academy of Raphael; and The Entombment of Christ of Caravaggio. For the first time, we know that the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel was painted by Michelangelo.

In contrast, do we know who painted the ceiling and the upper parapets of the Great Temple in Thanjavur? Do we know who made the later paintings in the same temple? Do we know who painted the Kailashnathar Temple in Kanchipuram?

Similarly, artists came to be known for their techniques. Chiaroscuro, the technique of contrasting use of light and dark in illuminating the subject, is known to be invented and developed by Leonardo da Vinci and Caravaggio, later to be taken to new heights by Rembrandt. Brunelleschi and Masaccio are credited for inventing, studying and codifying the rules for incorporating perspective in painting. Rembrandt, for the first time, shockingly makes the common man his primary subject, largely abandoning the sacred in art.

At first, when the artist enters the art, there is a frenzy of innovation resulting in a plethora of different beautiful creations. I love Caravaggio, most of Michelangelo; the northern masters like Vandyke; and the landscape painting that became popular during the Northern Renaissance and which became the only forte of the British in art. The best art strikes a balance between the universal and the particular. The universal makes it meaningful and relatable to the audience, and the particular makes it interesting and peculiar to the said artist or school of art. A piece that is only universal has no originality in it and is at best a copy. And a piece which is completely particular has nothing relatable in it and becomes an incomprehensible piece that is meaningful only to the artist.

That is why there are only a definite number of radical innovations that can keep art arresting and relatable. This number of combinations starts running out very soon, once the artist enters the art. While creativity is endless, when the artist is determined to ‘create something new’ he is not just competing with his contemporaries but also with his predecessors. In a bid to introduce something new, his predecessors too had taken out one after another of the universal elements, till very few were left. The universal and the relatable at last are reduced to zero. What is left is particular and strange. This is when art stops meaning anything to the audience and becomes a strange and ugly piece, meaningful only to the artist.

ART RECEDES INTO THE EGO OF THE ARTIST

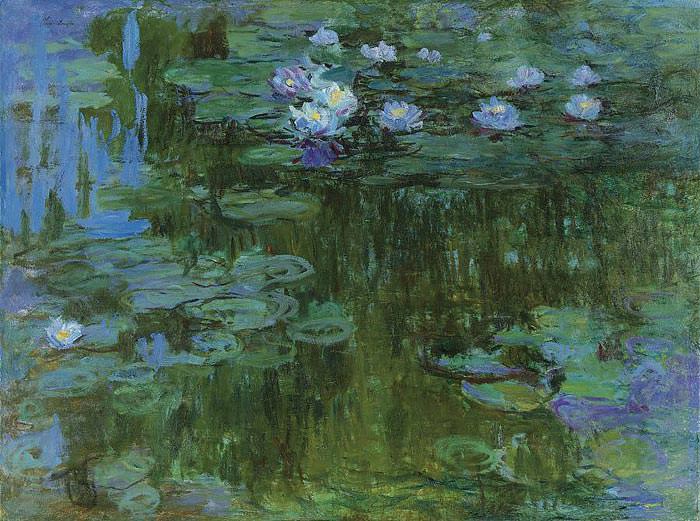

By the time of the Impressionists most of the creative ideas to tweak a painting had been exhausted. However, the Impressionists hit upon an amazing technique. They argued that from a distance, the vision is not clear and the objects blur into each other, giving an ‘impression’ of various objects. They argued that the artist has to create a scene as it ‘appears to the eye from a distance’ and not as it is.

The Impressionists argued that the painting should be made as it looks and thus there was no need for the boundaries to be clearly defined; there was no need to mix colors at the edges. They should be made fudgy by the artist himself. They used broad brush strokes and not well-defined boundaries in objects. These broad ‘unfinished looking’ strokes did not look very appealing from up close, but from afar they gave an impression of a complete landscape, hence the name. In this way, the artists argued, they were going for naturalism or realism in art.

Their remark on realism was predicated on the earlier religious art; particularly the chiaroscuro in which light surreptitiously and mysteriously illumined the subject of the painting. The artist did not pay attention to the source of the light. In an Impressionist painting, all this was kept in mind: the source of light, the texture of different objects seen from a distance.

In a way, the Impressionists were replicating as a scene would actually look rather than how it actually was. So even though they focused on realism, they were working upon the reality as perceived by the human eye and not as it really was.

Already the art was receding into the subjective realms of the individual artist. This subjective was not the subjective perspective which is the result of divine inspiration coming out of meditational trances, representing an aspect of the ultimate truth. This subjective was idiosyncratic and the strange of the individual ego of the artist thus concerned.

They were moving more towards the particular, even though they argued that they were coming nearer to realism. Undoubtedly they created some superb pieces. I love the soothing colors and dreamlike yet realistic landscapes that Monet created. However, Pandora’s Box of the individual artist had been open for a while now, and with every new step, the Universal was disappearing into the strange and the particular.

ON THE MERCY OF THE INDIVIDUAL MIND

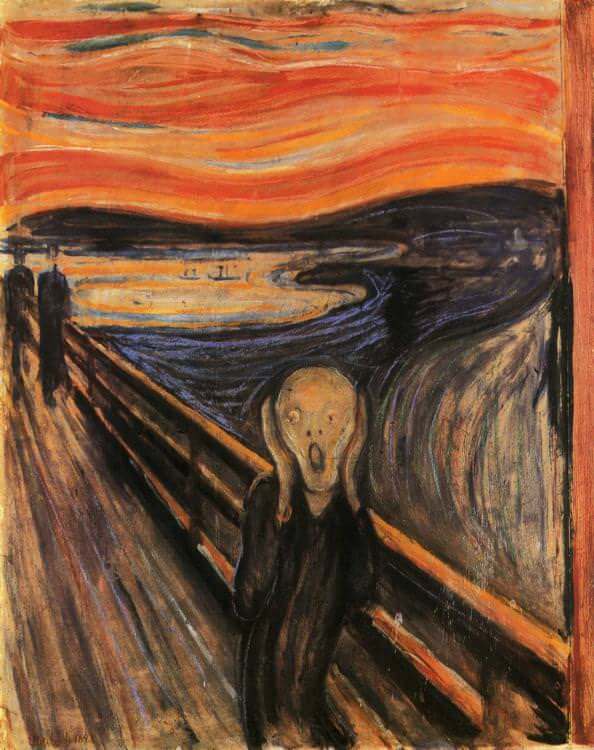

After the Impressionists, the Expressionists argued that why stop at how the eye perceives it? Why not move over to how the mind perceives or imagines it? That is, they moved from the visual to the completely mental perception of art. And thus we have The Scream by Edvard Munch. Once again, Munch was an acclaimed artist, and even after all the chaos of ideas he produced some notable works. But the progress downhill continued and art kept degenerating into increasingly unrecognizable forms.

Fauvism that came after Impressionism argued that instead of the reality as perceived by either the ‘eye’ or the ‘mind’, an artist, a painter, has to completely focus on the ‘painterly qualities’ and become completely subjective, not at all caring what the reality is, looks like, or feels like. The only objective of the painter should be to experiment with his techniques and in a flamboyant manner. Henri Matisse is an example who still salvaged some remarkable portraits out of this, but it was all headed downhill.

HOW THE TOOLS TO CREATE GOOD ART WERE DESTROYED

Then came Abstract Art. Wassily Kandinsky, the grandfather of almost all modern abstract art and a massive influence on all art movements, declared that an artist has to be ‘completely free’. By which he meant that not only should the artist ‘break all boundaries’ in case of art, he should also break the boundaries in case of his craft too. Not only the ‘what’, but the ‘how’ of the art should also be changed. And thus we ended up with geometrical forms with no human or natural image in them: just haphazard semi-geometrical forms. One saving grace was that Kandinsky used soothing colors.

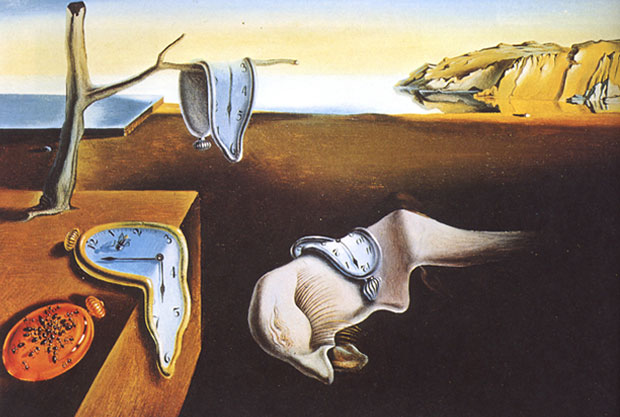

Then came two movements riding together: Surrealism and Dadaism. They often coincide with art installments and artists. Many artists were common in both. Together, they represent the very death of painting in the Western tradition. Salvador Dali created one immortal piece, The Persistence of Memory. That molten clock in the painting has become the stuff of legend. Except for this painting and one or two others by Dali, all else in Surrealism is a naked travesty of everything aesthetic, meaningful, and artistic.

Most of the Surrealistic paintings are nothing more than a horrible and horrifying mélange of human entrails, industrial scrap, pieces of turds, shards of the toilet, along with everything else that is ugly in the human imagination. In fact, the Surrealists went so far as to break all boundaries of the discipline of painting itself and most of their works are not called paintings, but ‘installations’ in which some part is painting-like, some is sculpture-like and some are the stuff of ugly horror movies.

The Dadaists put the last nail in the coffin by espousing nonsense and irrationality in art. They stood art on its head by embracing the ugly instead of the beautiful and the nonsensical instead of the meaningful. Hans Richter says that Dada was not art: it was ‘anti-art.’

They argued that it is the duty of the artist to keep ‘destroying stereotypes and boundaries’ and as everything that exists is stereotypical and has boundaries so everything has to be destroyed. Once in a live installation an ‘artist’ put some live goldfishes in a transparent mixer in front of a live audience and then turned on the mixer. The revolting mixture of blood and goo in the mixer was presented as art.

By this time not only was good artistic tradition destroyed: the very tools of creating good art were also destroyed. The ideology which dictated that there is no such thing as good or bad art, just art, also taught that there is no such thing as good or bad crafts, just crafts. It no longer mattered whether an ‘artist’ was skilled in his crafts, skilled in wielding his tools or not. He just needed to follow the right ideologies; follow the right artistic fashions of the Avante Garde movements of his time and he would be judged by these and these alone. Crafts no longer mattered.

TEACHING ‘ART’ AND NOT CRAFTS

A bitter result of this was seen in art schools all over the world. They stopped teaching crafts altogether. In traditional societies, all reputed artists worked as apprentices of great masters for years before they qualified to be called artists themselves. Thus an aspiring architect would just break stones for years with the hammer to fish out smaller pieces before the master actually handed him the finer chisels for sculpting. Any artist learned every step of the art that is involved in creating a final masterpiece.

This was what the traditional schools of art taught: crafts. The art they believed came from divine inspiration. What remained to be taught was how to handle the tools of the craft. In a classical reversal of roles, modern schools of art do not at all focus on teaching the crafts or tools of creating art. They consider it plebian and beneath great artists. Judging someone based on his ‘skills’ is now considered elitist and bourgeois. What is actually taught is ‘art’, or the ideology that now goes by the name of art.

By the time of the Surrealists and Dadaists, the painting had died a horrible death. And it all started with one wrong step taken in the Renaissance: to introduce the artist in the art; to introduce the painter in the painting.

Once that had been done, individual innovations trumped traditional themes; strange triumphed over the universal and the archetypal, and idiosyncratic eccentricity triumphed over meditational poise. In the search of the ever new, the strange became the goal. And the strange kept becoming uglier and uglier till it was not only unrecognizable but also deeply revolting.

The artist had completely arrived in the art. And consequently, the art was dead.

REFERENCES

1. Coomaraswamy, A. K. Introduction to Indian Art. Munshiram Manoharlal, 1947. (2017 edn.)

2. Rao, S.K. Ramachandra. Encyclopedia of Indian Iconography: Hindus-Buddhism-Jainism. Indian Book Centre, 2003.

3. Welch, Evelyn. Art in Renaissance Italy 1350-1500. OUP, Oxford, 2000.

4. Kramrisch, Stella. The Hindu Temple. Motilal Banarsidas, 2015.

5. Thomas, Denis. The Age of the Impressionists. Chancellor Press, 1992.

6. Waldberg, Patrick. Surrealism (World of Art). Thames & Hudson, 1978.

Explore The Artist in the Art Part I

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.