In the last article, we saw how the Hindu temple is pulsating with meaning and speaks the language of spiritual symbolism through every structural part of its architecture. We also saw how Islamic architecture in India, despite being aesthetically exquisite, failed to convey higher truths of life and existence to its visitors.

We studied how Christianity destroyed the spiritual foundation of sacred architecture in Europe. In the second part, we will see how the loss of meaning and the introduction of the architect in architecture led to the degeneration of the architectural tradition in the West.

The Exile of the Sacred in Post-Pagan Europe

Though Hindu architecture took the sacred meaning to its height in its construction techniques, other architectural idioms all over the world were not devoid of spiritual meaning either. All pagan architecture like the ancient Greek buildings or the Chinese pagodas and the Shinto temples in Japan pulsated with meaning.

Omiwa Jinja, Nara, Japan – A Shinto Shrine

Most pagan architecture like Hindu temple architecture was unnamed and did not mention the name of the architect. In Hindu architecture, the architect is completely absent from his creation. Instead, the cosmic architect, Lord Vishwakarma, is attributed with every creation. The archetypal architect, the divine agency, the devata, and the supreme principle replace the individual genius of the personal architect.

This foregoing of all individuality in favor of the divine principle and the divine doer is impossible if the meaning of creation is not spiritually elevating. When the Hindu architect abandoned the name in favor of divine bliss, he did that for he knew that his creation would transport millions during his time and till eternity to the higher planes of consciousness. Such an ennobling goal and such a deep meaning transcended his individual ego.

When Christianity invaded Europe and destroyed paganism throughout the Greek and Roman cultural spheres, something was irrevocably lost. When the Christian fanatics burned pagan philosophers, destroyed pagan temples in Athens and Rome, and myriad other cities all throughout Europe and the Mediterranean, they did not just destroy physical structures but managed to destroy a complete knowledge system. (Nixey xxxiv)

When they destroyed the sculpture of Zeus in Athens and Jupiter in Rome, they destroyed the ancient ways of knowing. When they destroyed the Parthenon in Athens or the Temple of Diana in Rome, they did not just destroy structures, but entire schools of symbols, symbols which were capable of transferring the greatest of truths in the simplest of ways.

When Christianity started raising its own monuments on the ruins of pagan temples, the sacred was exiled from architecture. The church was a religious building, but not a sacred one. It was meant for prayers and for communion. The purpose was social, political, and religious but scarcely spiritual.

In a pagan temple, deepest of spiritual mysteries were discussed; mystical experiences were had with consciousness enhancing drugs. People could meditate there and contemplate on the divine. The church, on the other hand, was very much an instrument of power and spoke in that language.

The Symbolism of Gothic Architecture

The symbolism did not disappear instantly. The early churches were quite simple affairs but by the middle ages, complex culture of church building had developed in Europe, particularly in the form of Gothic architecture which spoke in terms of symbols and incorporated symbolic devices through structural components of the architecture. Though the overt symbolism was Christian, the spirit of meaningful architecture was thoroughly pagan.

Reims Cathedral – A Gothic Masterpiece

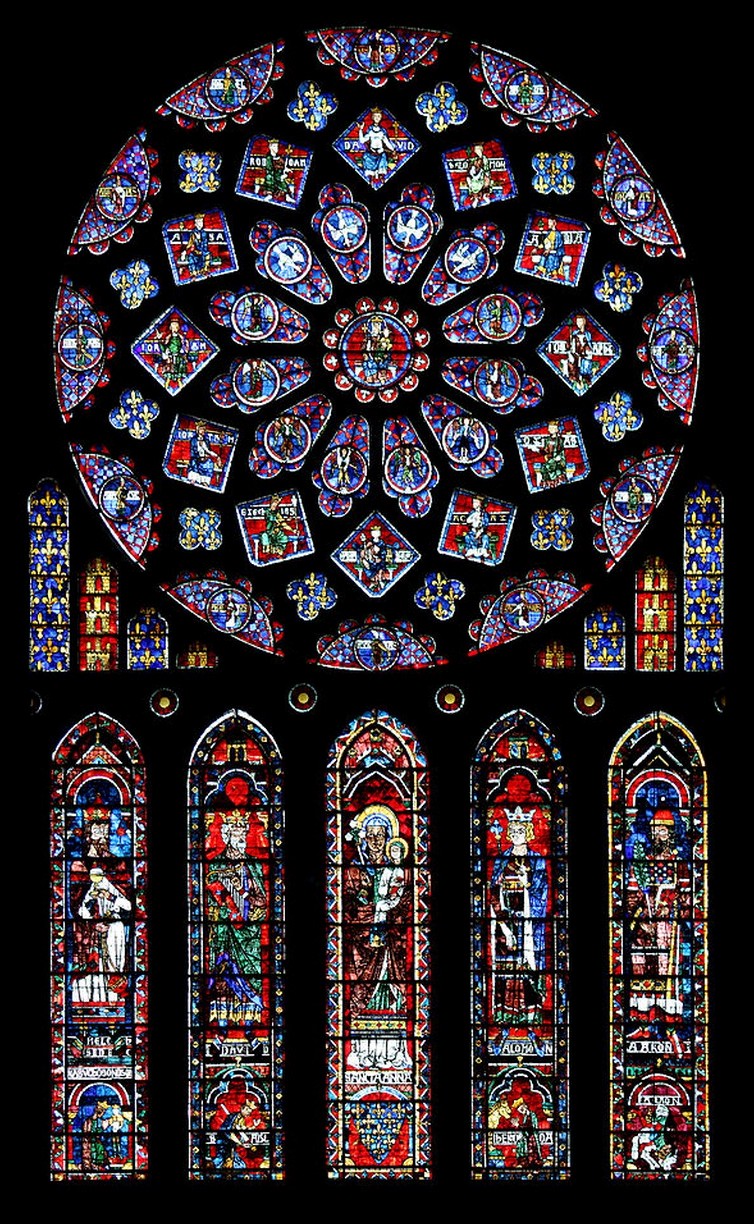

Through its sky-scraping pinnacles and spires, the Gothic cathedral tried to speak a heavenly language. Using stained glass in a way in which it has neither before nor after been used like this, the Gothic church sculpted natural light into meaningful stories. The play of light and darkness was used upon the visitor for the sake of impression and power but also for the sake of telling a story.

Stained Glass Window – Chartres Cathedral, France (Gothic)

The façade was not just used to impress with its scale and height but also through its symbolism. In the 13th century Reims Cathedral in France, the façade is sculpted all over. “Approaching the principal west façade of the cathedral of Reims, where decorative carving extends from the ground to the summit the viewer’s eye is drawn upwards to the scene of the Coronation of the Virgin in the gable above the central west door…” (Sekules 90)

Reims Cathedral – West Face – Front Facade (Gothic)

From the outside symbolic sculpture and architecture told the story to the visitor. As the visitor entered inside the stained glass windows led the way in telling the story through their beautiful play of light, color, and darkness. The invention of the historiated capitals meant that every pillar, (and there were a huge number of pillars in a Gothic building) would tell a story.

The particular style of building in Gothic architecture ensured that in all aisles there was a possibility of creating small chapels of the Virgin Mary and other Angels, thus providing small cubicles like private spaces. This kind of building was capable of more than prayer and congregation. That Christianity lacked a spiritual core is a reason this architecture never evolved to arrive upon the meaning that the Hindu architecture conveys.

The Loss of Meaning

These tools of conveying meaning which had been lingering on in the motifs of Gothic Architecture in medieval Europe disappeared soon after the Renaissance took root and neo-paganism started guiding the Renaissance architects. In sculpture and painting, pagan themes experienced a major revival during the High Renaissance, but this revival did not touch the spirit of paganism but only overtly took its themes and used its mythology as the subject matter of the artist.

Passed through the Christian sieve, the paganism that seeped through to the Renaissance artists was devoid of its meaning and soul. The form made through the ages, the spirit was lost in translation. In architecture, this effect was more severe, as the very means of conveying meaning which pagan cultures of ancient Greece and Rome had incorporated inside them were completely lost and more so in the urgency to reincorporate the science and technology of ancient Greece.

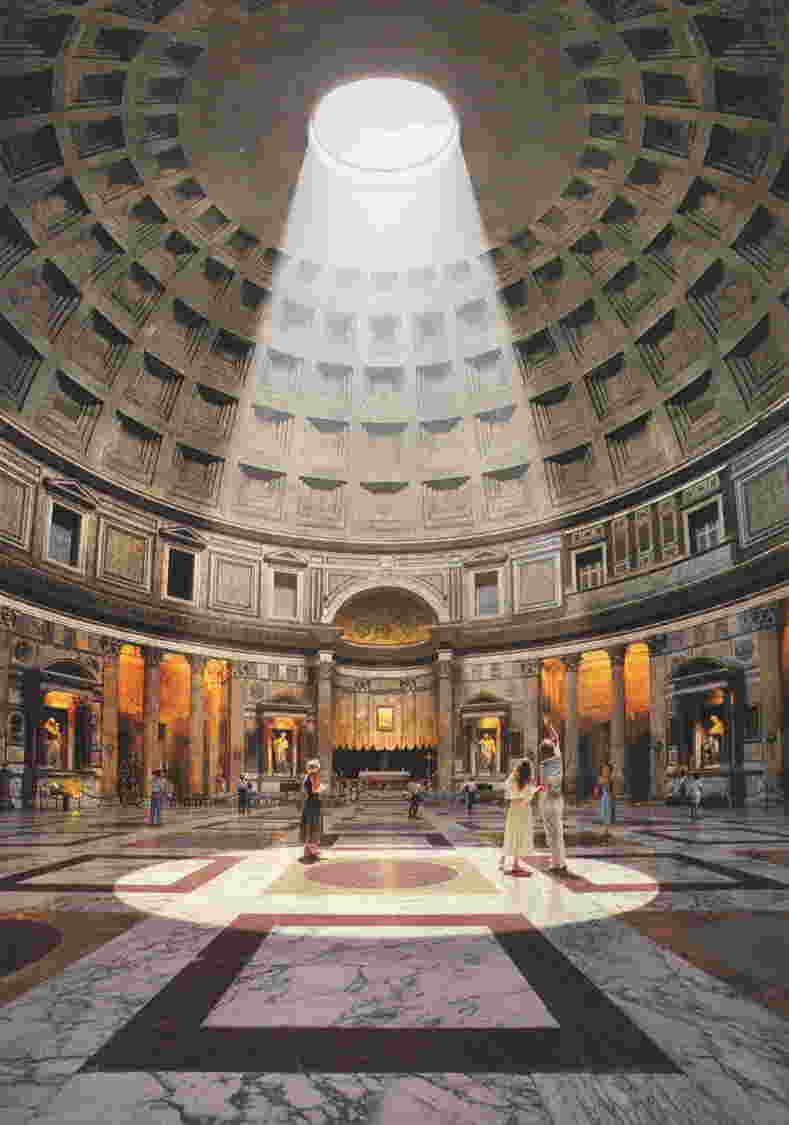

The discussions that went on in the creation of Brunelleschi’s Dome or the Oculus at the Pantheon did not figure symbolism anymore. The discussions were technical and scientific: how big a dome can be without the support of the flying buttresses? Or how could they distribute the weight of the dome? How to bring more natural light into the building? (Murray 24)

Brunelleschi Dome – Florence Cathedral (Renaissance)

All of these were great advances in building techniques and really brought about welcome changes in European Architecture and then later all over the world. They once again built upon Vitruvius and other Roman and Greek architects of antiquity. They relearned the pagan techniques of building, but only those which were functionally useful for them.

The Oculus at the Pantheon – Rome (Renaissance)

The spiritual meaning which had managed to linger on in the medieval architecture went missing in Renaissance architecture and the pagan meaning of the ancient Greek temple was never transferred. Put through first the Christian sieve, and then the rationalist and humanist sieve of the Renaissance, the spiritual meaning and the spiritual techniques of the building were gradually lost upon the Renaissance architects.

The Individual Architect Arrives

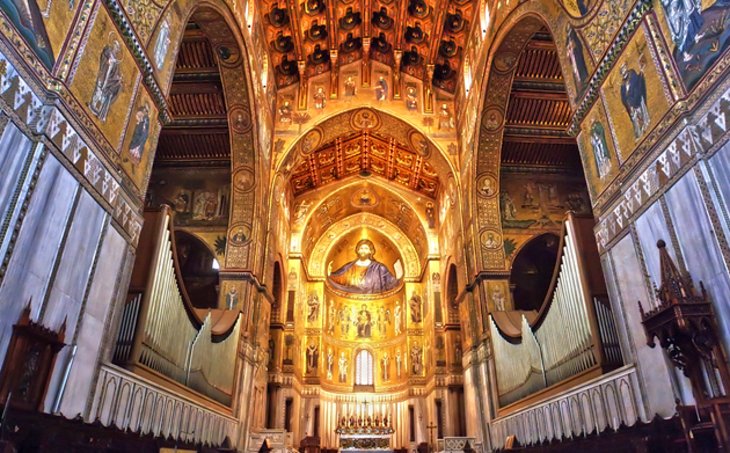

Just like in painting, the individual architect was gradually becoming important. Even in the medieval ages, we find the architect surreptitiously signing himself into the building at various places throughout Europe, like in the Monreale Cathedral in Palermo, Sicily. The loss of spiritual core during the Holocaust of paganism perpetrated by Christianity and the gradual loss of meaningful architecture during the Middle Ages meant that the architects could no longer remain anonymous.

Monreale Cathedral – Sicily

The church was increasingly becoming a power statement. Richer kings built higher churches. The impression of the scale was gradually winning over the impression of meaning. It was only a matter of time before the architect who actually built a piece of the building would start feeling to be as important as the patron who commissioned it. It is significant that even in the medieval ages, it was Italy which led Europe in having the most number of signed buildings, as Sekules says:

“A greater number of examples of such praise for identified sculptors has survived in Italy than elsewhere in Europe.” (Sekules 53)

In the High Renaissance, we get great names of architects such as Raphael, Michelangelo, and Brunelleschi. Particular buildings are attributed to them and their genius. Florence Cathedral and its famous Dome, now known as Brunelleschi’s Dome made the fortunes and fames of many of these famous architects. Once the symbols were out and the meaning was gone all that remained was aesthetic and technical innovations and individuals who make them could not help but be proud of them.

Baroque: The First ‘International Movement’

The architecture was still more of a collaborative art than other arts. Many architects worked on the same building and it was impossible for any architect to put his ideas on the ground without the patronage of a great king or a nobleman. Thus the ethnic and the regional character were still important after the High Renaissance had passed. But what characterized these ‘schools of architecture’ and these movements, were their peculiar and ‘strange innovations’.

Santiago de Compostella – Spain (Baroque)

In Baroque, the façade remained simple and the innovations of the Renaissance were enhanced and used to the full but what characterizes it is the profuse interior decoration. The great age of soirees, balls, and parties that were immortalized by Lev Tolstoy and Jane Austen later was just starting. And the grand halls in which these balls and parties took place were more often than not Baroque and Rococo.

More than ever, the social life of Europe was receding inside the closed rooms and huge and high ceilinged halls. It was imperative that ‘interior designing’ became more important and a ballroom became more decorated on the inside than the outside.

Church of Saint Ignatius of Loyola, Rome, Lazio, Italy (Baroque)

Every inch of the interior is full of painting, terracotta sculpture, and gilding. The gold color is used everywhere. Showing off was the norm of the day. But what characterizes Baroque and Rococo the most is their obsession with staircases. An architecture movement that had a profusely decorated interior was forced to invent pedestals to watch and admire the fine work that covered every inch of the walls.

In many of the balls discussed above, the hosts and the important dignitaries would often descend from a magnificent staircase to the admiration of the audience in the hall.

Salon of the Hôtel de Soubise in Paris (Rococo)

What is characteristic of Baroque and Rococo is that the search for spiritual meaning is almost abandoned. Ostentation and ornamentation for its own sake is the norm. A natural reaction occurs in the neoclassical movement which strips the ornamentation a little too much. We can clearly see that by the 18th and 19th centuries, movements were rising and falling rigorously on the Western architectural scene, but their direction seems to be random. The search for meaning is lost and it is movement specific idiosyncrasies that characterize them.

Global Movements in Architecture

With the arrival of the colonial age, global movements also started arising. Many claim Baroque to be a first truly global movement, but its transplantation on other continents like South and North America was merely the work of the colonial masters.

It was the Eclecticism of the 19th century that truly declared the directionless character of modern architecture. Proud proclamation of the incorporation of whatever elements that struck the fancy of the particular architect, the loss of meaning in architecture could not have so evident. Eclecticism did not just incorporate different idioms of different cultures; it also incorporated the new building materials. The organic nature of curved lines and figures was abandoned in favor of straight lines and geometrical figures. Ornamentation was also not favored.

Art Nouveau was another international movement that was self-conscious of bringing something ‘new’ to architectural history. The urge to create something new was becoming the primary urge in architecture. However, Art Nouveau was also a reaction to the eclecticism of the 19th century and brought back curved lines and natural decoration in architecture.

But it can be safely said that there was only one great architect, one great artist, Antoni Gaudi who practiced this organicism in architecture completely. We know Art Nouveau through Gaudi’s work which uses aedicules and fractals in the building. Structural components play a function as well as embellish the building. But Gaudi was one architect who never became a tradition and seldom could any other artist pursue what he started.

Casa Batllo – Barcelona – Antoni Gaudi (Art Nouveau)

This was inevitable. Once the meaning in architecture is lost and once the sense of the sacred is gone and once the national, racial and regional characteristics are also stripped away one by one, any accidental arrival upon the meaningful way of creating architecture is bound to be buried into sands once the artist who rediscovered it is dead. The same happened with Gaudi. His line is rarely followed in modern architecture.

Ceiling of Antoni Gaudi’s Sagrada Familia, Barcelona(Art Nouveau)

Modernism arrives with full force in the Expressionist school of architecture where ‘stories and experiences of the World Wars’ are ‘incorporated into the body of architecture’. Architecture, which was a sacred means of communication in ancient times, becomes an ideological tool in modern times. The personal story of the individual architect becomes more important than architecture itself.

The arrival of Art Deco means that for the first time reinforced concrete along with glass and steel architecture is not only accepted as an industrial era necessity but also celebrated as a tool of ‘new aesthetics’. We are supposed to believe that reinforced concrete can be beautiful.

It, however, retains the need for ornamentation or decoration and is vainly decorative like the Chrysler Building or the Empire State Building in New York. Architecture has not been brutalized completely yet.

Chrysler Building – New York (Art Deco)

By the 1940s, even this ornamentation and decoration is abandoned in favor of straight lines, flat surfaces, and the inhuman cubist blocks and chunks of naked concrete. This was called the International Style of Architecture. For something to be truly international, all regional characteristics have to be stripped away. What remains is the rigidity and brutality of industrial-era architecture. Architects like Le Corbusier ‘celebrate concrete’ in all its naked brutality. His buildings look like solid blocks of concrete, with nothing organic relieving the inhumanity of the structure.

Villa Savoye – Paris by Le Corbusier

Ever since the arrival of Art Nouveau the style had become the primary marker of difference and distinction with meaning and symbolism long having been lost. Various movements like Critical Regionalism, Postmodernism, and Deconstructivism are more ideas than buildings. They are the result of the idiosyncrasies of individual minds. Postmodernist and deconstructivist ideas that destroyed painting, poetry, drama, and literature also destroyed architecture to great extent.

Deconstructivist buildings look like nothing more than a heap of unorganized junk thrown away, or pieces of a previously coherent structure strewn all over without care. In some words, these buildings convey ‘controlled chaos’. In other words, they are the result of the architect’s whim and result of his confused and deconstructed mind.

Vitra Design Museum – Germany by Frank Gehry (Deconstructivism)

Brutalist architecture does not even attempt to hide what it does. It does not just expose the brutal aspects of architecture to the public eye but reinforces them. It reinforces ideas of concrete building materials and exposed structural elements. Thus bricks are not plastered over; concrete is not painted over. Geometrical shapes are all you can see in the patterns and the colors are also sepia or monochrome with hardly any different colors relieving the scene.

The Soviet Union with its ‘art for utility’s sake’ argument favored this kind of architecture. Many of these buildings still pay testimony to that past. A lot of socialist countries like India also built many buildings in this vein.

Giesel Library – San Diego (Brutalism)

The Aura of the Individual Architect

In the modern era, particularly in the late 19th century and in the 20th century, architects became law in themselves. There was no longer any spiritual tradition in place to guide them. There was no particular meaning that they wanted to convey. Architecture like much else became a matter of individual whim and fantasy.

Whatever the architect fancied in his whim started taking shape in the form of his building. Since there were no spiritual traditions to guide them in meaning; no cultural glue to bind different architects in one architectural idiom; and no more defining national or regional characteristics to bring their creations together, every architect became an island in himself and started creating strange buildings.

Some of the most iconic buildings of modern times are often no more than the representation of the idiosyncrasy of the architect that built it. In a traditional society, such idiosyncratic elements would be negligible and more often than not condemned.

In a Hindu temple, these are minimal. For example in some temples like the Ramappa Temple in Warangal, we see more importance given to the Naga Kanyas which adorn the area beneath the cornice. But this is an exception and in most cases idiosyncrasies are condemned and the artist is recommended to conform to the philosophical principles of his culture and civilization, trying to create a piece of architecture that conveyed Hindu philosophy most potently.

Dancer – Ramappa Temple, Warangal

But in modern architecture idiosyncrasies were celebrated and even required as a necessity. Ayn Rand, building upon this intellectual climate, made a whimsical, introvert, anti-social and idiosyncratic architect as her hero. Atlas Shrugged is the Bible of many modern architects, not for its instruction on architecture, which is negligible, but for its celebration of whimsicality and idiosyncrasy.

As the art of photography developed and aerial photography became a thing with panoramic shots becoming more common than before, the architects began to see their buildings from a distance, gradually becoming more and more conscious of how ‘they looked’ from afar. Architects in a traditional school were also concerned about how their creations looked, but never exclusively so. Like in a Mughal tomb or a Renaissance Palace, in modern architecture the building often became what it looked.

The discipline of photography reverse impacted the individual architects who started to think exclusively in terms of how their buildings looked from afar. Frank Gehry created buildings that often look like different colored tin shards thrown together like the Walt Disney Concert Hall, Los Angeles, California. Sometimes they seem to defy gravity as the Dancing House of Prague. Sometimes they look horribly like a particular object, like the Day Complex Venice, California which looks exactly like binoculars. Sometimes it is all glass and steel rims like the IAC Building, New York.

Lou Ruvo Center, Las Vegas, Nevada by Frank Gehry

Norman Foster’s now-iconic building in London called The Gerkin looks exactly like the Gherkin. That much is an achievement, but why does it look like a gherkin, if one asks, then there is no answer. Renzo Piano’s building, The Shard looks exactly like a shard but why does it look like once again goes unanswered. Rem Koolhas made the Television Headquarters in Beijing look like a Mobius Strip for no evident purpose.

The Gherkin – London by Norman Foster

On the other hand, there is a very specific and definite reason why a Latina Nagara shikhara in the Hindu temple looks like that.

Shikhara of Mukteshwar Deuala, Bhubaneswar

If Le Corbusier’s buildings looked like brutal blocks of concrete, then those who revolted against such architecture, like Oscar Niemeyer, purposefully introduced curves in their buildings even where they have no structural or functional place like at Oscar Niemeyer Museum at Curitiba, Brazil.

Oscar Niemeyer Museum in Curitiba by Oscar Niemeyer

Zaha Hadid who was hailed as the ‘queen of the curve’ for ‘liberating architectural geometry’ in her works curved everything for just the sake of it. Why rigid geometrical designs of cubes and rectangles were introduced in architecture and what was the need for another movement to go to the other extreme of curves is a question students of architecture schools are too afraid to ask.

Heydar Aliyev Centre in Baku, Azerbaijan by Zaha Hadid

Strange is the New ‘Beautiful’

Lev Tolstoy in the iconic first sentence of Anna Karenina says: “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” Similarly, there are only a certain number of ways in which a meaningful and functional building can be created, but infinite ways in which meaningless inanities arising out of individual whims, personal idiosyncrasies and ideological fashions can give rise to a building. These buildings and these architects are prized for their ‘different’ take and meaningless ‘innovation’. The search for difference becomes the search for strange.

Just like a Mughal tomb or a Persian cenotaph, the modern building is built purely for the aesthetic effect. There is no meaning in all these buildings. Though the architects claim the highest of meanings for these buildings there is no objective criterion by which they can be judged. They ‘have to be looked with the architect’s eye’ which simply means that the building does not give itself to any traditional symbolism or meaning and has its own logic which is better not questioned, for ‘true art cannot be judged’.

These buildings are what they look like: just beautiful pieces of architecture. Their material aspect cannot be more emphasized. There is a certain voyeurism about them. The looks are so highly prized that every other function takes second or no priority.

The beauty of the Hindu temple or the pagan temple in Greece lies in its wonderful quality of using the most concrete of mediums to convey the most abstract and most spiritual ideas. The architects of the Hindu temple in India created canons of iconography, sculpture, and architecture which made sure that the highest of truths were conveyed through a concrete medium like architecture.

In modern architecture, this spiritual communication breaks down completely. For a medium to be called communicative, just like a language, a huge number of people have to agree upon shared symbols and common metaphors. In a traditional piece of architecture, this is exactly so. Everyone in ancient India who visited a temple knew what a certain Hasta Mudra meant to convey, and what the Nataraja pose meant to convey. In modern architecture, nobody apart from the architect himself can truly ‘understand’ what he means to say, which is another way of saying that there is no meaning in modern architecture anymore.

And while the Humayun’s Tomb or the Florence Cathedral is doubtlessly and wonderfully beautiful, the modern building does not even fulfill our aesthetic desire. With the help of the University System, art critics, humanities professors, and architecture schools the very definition of aesthetics has been stood on its head. Strange is the new Beautiful. And Ugly can be strange too. Until it is strange, nobody cares. Even ugly is accepted in the name of ‘innovation’.

A beautiful building now is something that is completely strange and completely whimsical based on whims and fantasies and idiosyncrasies of the individual architect. The only criterion to judge is the criterion invented by the very same architect who created the building. Such a system of criticism is fool proof of any criticism. For if there is no objective criterion to judge a building the only criterion left to judge is the criterion of the architect.

In a classic case of inverting the meaning, the modern architecture has managed to call ugly as beautiful, and in a system where objective criticism of art and architecture is no longer possible, where no spiritual system exists anymore to impart meaning to the building, and where no ethnic, cultural or national culture exists to guide the style of the architect, every building is a beautiful building, no matter how ugly it looks to us, and no matter how impractical it is for use.

And it all happened with two momentous changes in the Western tradition of architecture:

- The elimination of the sense of sacred and the obliteration of the spiritual meaning from architecture by Christianity.

- The introduction of the individual architect, who devoid of the urge to dedicate buildings in the service of spiritual meaning and to the agency of the cosmic architect, started on the search for the ever new and ever strange, without giving any thought to the meaning of architecture.

References

- Sekules, Veronica. Medieval Art – Oxford History of Art. Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Nixey, Catherine. The Darkening Age: The Christian Destruction of the Classical World. Pan Macmillan, 2018.

- Seznec, Jean. The Survival of the Pagan Gods – The Mythological Tradition and Its Place in Renaissance Humanism and Art. Princeton University Press, 1995.

- Murray, Peter. The Architecture of the Italian Renaissance – World of Art Series. Thames & Hudson. 1969.

Explore The Importance of Hindu Architecture Part I

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.