The Bhagavad Gīta enjoys an exalted place in the Vedāntic firmament. Over 200 commentaries (bhāṣyas) have survived in the Sanskrit language alone, making it perhaps the most extensively studied text in the Indian tradition.

In our times, there is a tendency to read literal translations of Bhagavad Gīta sans any commentary. Even when commentaries are alluded to, it is usually those of Adi Śankara or Rāmānuja, or in some cases a new bhāṣya like that of the 20th century Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇava teacher – Prabhupāda.

The commentary of Śankara is the earliest extant commentary on the Bhagavad Gīta, and the most widely cited in scholastic circles. Yet my personal observation is that there is a tendency to underrate later medieval commentaries.

Some of the later Bhāṣyas are often much more comprehensive and thorough in charting out the intellectual history of specific ideas discussed in the Gīta than the earliest Bhāṣyas like those of Śankara or Rāmānujā, that are often fairly terse.

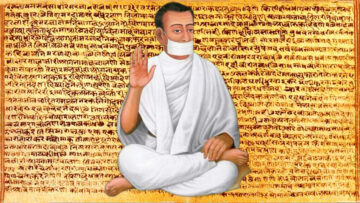

One such late medieval commentary is that of the great 16th century Advaitin – Madhusūdana Sarasvatī. Though Madhusūdana Sarasvatī was a man of many accomplishments, perhaps his greatest work is his commentary on the Gīta – the Gūḍārtha Dīpika.

Unlike the older commentaries we alluded to, the Gūḍārtha Dīpika is a voluminous work. It is anything but terse, with commentaries often running into several pages for a single ślōka!

First let’s get some background on Madhusūdana Sarasvatī. He was a native of modern Bangladesh, who was born as Kamalanayana. His ancestral roots however were in Madhyadeśa, with an ancestor named Rāma Miśra Agnihōtri migrating to Bengal from Kannauj in the 12th century. While he was an Advaitin, he was also curiously an ardent Vaiṣṇava – a combination that is not too common.

His “Advaita Siddhi” is a famous riposte to the Dvaita classic “Nyāyāmṛta”

authored by Vyāsatīrtha – the scholar patronized by the Vijayanagara Empire. But it is his bhāṣya on the Gīta that is his most popular work.

In this essay, we will examine Madhusūdana Sarasvatī’s bhāṣya on a single Gīta verse – Verse # 35 of Chapter 6 on Dhyāna Yoga. The essay leverages the translation of Madhusūdana’s work by Swami Gambhirānanda of Rāmakṛṣṇa Maṭha.

The verse in consideration is reproduced below. It is a famous ślōka that many readers are likely to be familiar with.

असंशयं महाबाहो मनो दुर्निग्रहं चलम् |

अभ्यासेन तु कौन्तेय वैराग्येण च गृह्यते || 35||

Here’s the literal translation of the verse by Swami Gambhirānanda of Rāmakṛṣṇa Mutt)

“O Mighty armed one. It is doubtless that the mind cannot be controlled and is restless. But Son of Kunti, it is restrained through Practice (abhyāsa) and Detachment (vairāgya)”

The earliest of our traditional commentators – Adi Śankara and Rāmānuja – gave fairly brief, straightforward bhāṣyas for this verse. Madhusūdana Sarasvatī in contrast provides a detailed commentary that runs into six pages in the English translation by Swami Gambhirānanda. His thorough and meticulous bhāṣya for this verse leverages two other texts –

• Laghu Yoga Vasiṣṭha

• Patañjali Yoga Sūtras

The key questions addressed by Madhusūdana Sarasvatī’s bhāṣya are –

1. Why is the mind fickle and naturally uncontrollable?

2. Can the mind be “violently” controlled the way we violently close our eyes, or close our ears? If not, what’s the alternative?

3. Are “abhyāsa” and “vairāgya” two alternative ways to control the mind? Or are both essential in the pursuit of stilling the mind?

4. What exactly is abhyāsa? What does it entail to make it successful?

5. What is vairāgya? What are the different kinds of it?

Let’s start with Questions 1 and 2.

“Why is the mind fickle”?

“Can it be controlled violently? If not what’s the alternative”?

Madhusūdana Sarasvatī attributes the fickleness of the mind to Prārabdha karma – the accumulation of karmas from the past that are experienced through the present body.

Next he also explains why the mind cannot be controlled the way we close our eyes or our ears. This may seem obvious. But Madhusūdana spells it out –

His reasoning is paraphrased below –

Unlike eyes or ears, the “locus” of the heart cannot be restrained. So to control the mind, you need a “regular method” not brute force. This regular method is Yoga.

He backs himself by citing Yoga Vasiṣṭha passages – a text authored perhaps at least 1000 years before Madhusūdana Sarasvatī’s own time.

Yoga Vasiṣṭha is a very voluminous text comprising of discourse by Vasiṣṭha to Rama. It is one of the largest texts in Sanskrit literature and used extensively by Madhusūdana in his arguments.

Madhusūdana quotes Vasiṣṭha who uses wonderful analogies to illustrate why Yoga is essential for controlling the mind, and why violence is futile.

“Controlling the mind without Yoga is like controlling a wicked elephant without ankusha (the hooked goad used by the mahout)”

Vasiṣṭha also cites the means that are available in Yoga to control the mind-

1. Mastery of spiritual knowledge

2. Association with holy men

3. Total giving up of desires

4. Control of the movements of the vital force

He adds –

“Those who control mind violently when these means are available, are like people who reject a lamp and instead remove darkness using collyrium (on their eyelashes)”

A wonderful analogy.

Madhusūdana agrees with Vasiṣṭha here. But he cites yet another passage from Yoga Vasiṣṭha that is pertinent to #3 and #4 in the above set of four means.

As per Yoga Vasiṣṭha, the “tree of the mind” has got two seeds –

a. Vāsanā – the latent tendency to desire

b. Movement of the vital force – prāṇa

Now as per Vasiṣṭha, both of these complement each other and contribute to the mind’s fickleness. But Vasiṣṭha distinguishes between the two and prescribes different means to counter both.

In Vasiṣṭha’s view –

- Movement of vital force is constrained through earnest practice of Prāṇāyāma, practice of āsana, and control of food.

- In contrast, Vāsanā is controlled through dealings without attachment, shunning of worldly thoughts, and observation of the perishability of the body.

From this Madhusūdana infers –

It is abhyāsa that is needed to control “movement of the vital force” and vairāgya to control “Vāsanā”.

So Madhusūdana Sarasvatī here is linking what Kṛṣṇa is saying about abhyāsa and vairāgya to the two “seeds” of the mind cited by Vasiṣṭha.

Madhusūdana now reminds us of the two other things Vasiṣṭha had prescribed earlier.

- “association with holy men”

- “mastery of spiritual knowledge”

But then concludes – these two are helpful for abhyāsa and vairāgya – but non-essential. It is not a surprise that Kṛṣṇa sticks to abhyāsa & vairāgya in the verse.

Then Madhusūdana reminds us of Patañjali Yoga Sūtra #12 in Chapter 1 – which reads

अभ्यासवैराग्याभ्यां तन्निरोधः॥१२॥

So Patañjali too agrees with Kṛṣṇa in suggesting that these two are essential for Nirodha (stilling the mind).

But Madhusūdana follows up with another beautiful analogy to explain what “nirodhah” is –

“It is the state that is best understood as cessation – like a fire without fuel stops burning”.

Cessation of Fire without fuel is a very apt way of explaining the goal being sought here.

Now we move to the third question posed earlier.

Are abhyāsa and Vairāgya both needed? Are they somehow related to each other? Or independent.

Madhusūdana again uses a remarkable analogy to explain why both are essential, and somewhat independent means.

To paraphrase his view –

“The river of the mind flows both ways (unlike earthly rivers) – one flows towards good, and one flows towards evil. Now the current flowing towards evil / non-discrimination needs to be blocked by a dam – which we can call “vairāgya”. Whereas the current that is flowing towards the good can be augmented by constructing a canal of sorts and channeling it – think of this as “abhyāsa”. So the dam and the canal serve different ends. Hence both are essential”

A brilliant analogy yet again.

Then he contrasts this with an analogy from Vedic ritual where you have genuine options –

E.g. In a Vedic ritual, you can make the sacrificial cake using either paddy or barley – that’s an option. But in this context abhyāsa vs vairāgya is not an option. You need both.

But then what exactly is abhyāsa. How does one make it work?

Madhusūdana goes into specifics here. And again cites Patañjali, Sutra # 14 Chapter 1

स तु दीर्घकालनैरन्तर्यसत्कारासेवितो दृढभूमिः॥१४॥

So here as per Patañjali (and Madhusūdana), abhyāsa is successful only if

1. It is fully adhered to without despondency (asevitah)

2. Adhered to for a long time (dīrgha kāla)

3. Adhered to without a break (nairantarya)

4. Adhered to with great regard / confidence (satkāra)

If all four conditions are fulfilled, then the abhyāsa is successful and becomes firmly grounded (dṛḍhabhūmih in Patañjali ‘s words)

Next Madhusūdana discusses vairāgya, again with the help of Patañjali , who lived some 1000+ years before him.

Vairāgya as per Madhusūdana is of two types – para (supreme) and apara (relative).

The relative vairāgya again comprises of four kinds

- yatamāna (engaged in effort to abjure the non-essential)

- vyatireka (exclude the non-essential through discrimination)

- ekendriya (longing for non-essential remains just a longing in mind, tempered by the realization that engagement in objects of pleasure is ultimately painful)

- vaśīkāra (complete absence of desire)

Now Vaśīkāra above does seem very “absolute”, but in Patañjali ‘s view, the absolute vairāgya is something different. It stems from desirelessness for the guṇas, which in turn stems from the direct vision of the Puruṣa (the absolute cosmic being)

Leaving aside the discussion on Abhyāsa and Vairāgya, Madhusūdana also finds space to explain the less important words used by Kṛṣṇa in the verse. One such word is “mahābāhu” (mighty-armed).

Now Madhusūdana explains why Arjuna can justifiably be addressed as mahābāhu by Kṛṣṇa. He cites the example of Arjuna fighting Shiva himself during his years in exile, a very well-known episode also memorialized by the poet Bhāravi in his mahākāvya “Kirātārjunīya”.

That specific episode, in Madhusūdana’s view, justifies the use of the term “mahābāhu” to address Arjuna!

This tidbit is particularly noteworthy. It is indicative of Madhusūdana’s eye for detail and trivia amidst all the philosophizing on the more abstruse parts of the verse.

This concludes our summary of Madhusūdana’s six-page dissertation on this single verse. The bhāṣya underscores the immense influence of the Gīta on the intellectual life of the country over two millennia.

Notice how Patañjali, likely an intellectual from the 4th century, is being used to rationalize the ideas propounded in the Bhagavad Gīta – a text that predates Patañjali by some thousand years if not more. Now in the 16th century, we have Madhusūdana using Patañjali ‘s arguments, 1000+ years later!

It goes to show how a seemingly innocuous verse has impacted thinkers separated by several thousand years. Also, its intellectual history is in constant development throughout that period from mid 1st millennium BCE to mid 2nd millennium CE.

Madhusūdana’s Gūḍārtha Dipika is indeed a very rich and under-studied work that ought to be read by more people who are interested in the Bhagavad Gīta. While we rightly look up to the traditional commentators from an earlier time (E.g. Śankara, Rāmānujā), we must not lose sight of the more comprehensive bhāṣyas written in the medieval period by the likes of Madhusūdana Sarasvatī.

References

Madhusūdana Sarasvatī, Gūḍārtha Dipika – Translation by Swami Gambhirānanda of Rāmakṛṣṇa Maṭha

Featured Image Credits: Iskcon

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.