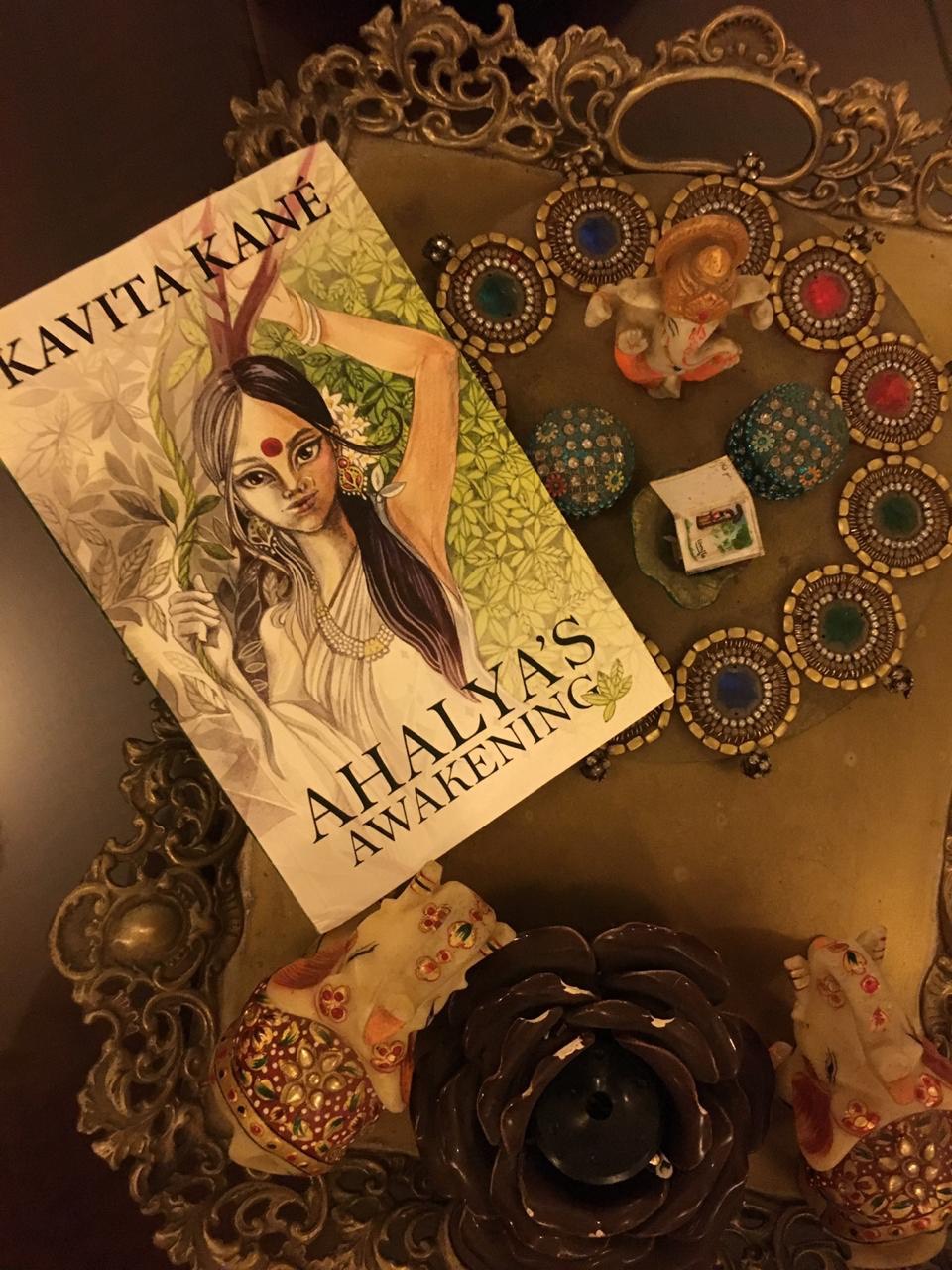

There are many women protagonists in Valmiki’s Ramayana and all of them operate in pairs, almost like a counter character. When one reads the original as Kavita Kané, author of the newly released Ahalya’s Awakening, has done again and again, one is not sure that there is indeed only one interpretation to the narrative.

“Each time, every time, several times I have gone back in the course of my research”, says Kané when asked about the reading of the original, “I have found something new – when you have to research you have to keep reading, re-reading, going back to it. Research involves not just reading texts but later versions, translations, folk threads, essays and comparative literature. The ‘source’ is often the amalgamation/ sieving of all such information collected.

Sita and Surpanaka, Kausalya and Kaikeyi, Tara and Ruma, Mandodari and Ravana’s other women, and the female ascetics Ahalya and Anusuya have all been the subject of interest for interpreters. Kané says our epics are a rich source material for interpretation, and Ahalya’s Awakening is one such offering. “The very fact that there are so many versions of the original story means that it has been interpreted and reinterpreted down the ages.”

Within the text, these women characters help in the exploration of character, relations and the story line. Some are the source of a series of subsequent turns in the story and some help in the understanding of importance of the Ramayana and Mahabharata in analyzing human psychology in its earliest expression. Kané has an understanding with her readers, they know that she has set out to popularize the epics and make them relevant to contemporary readers.

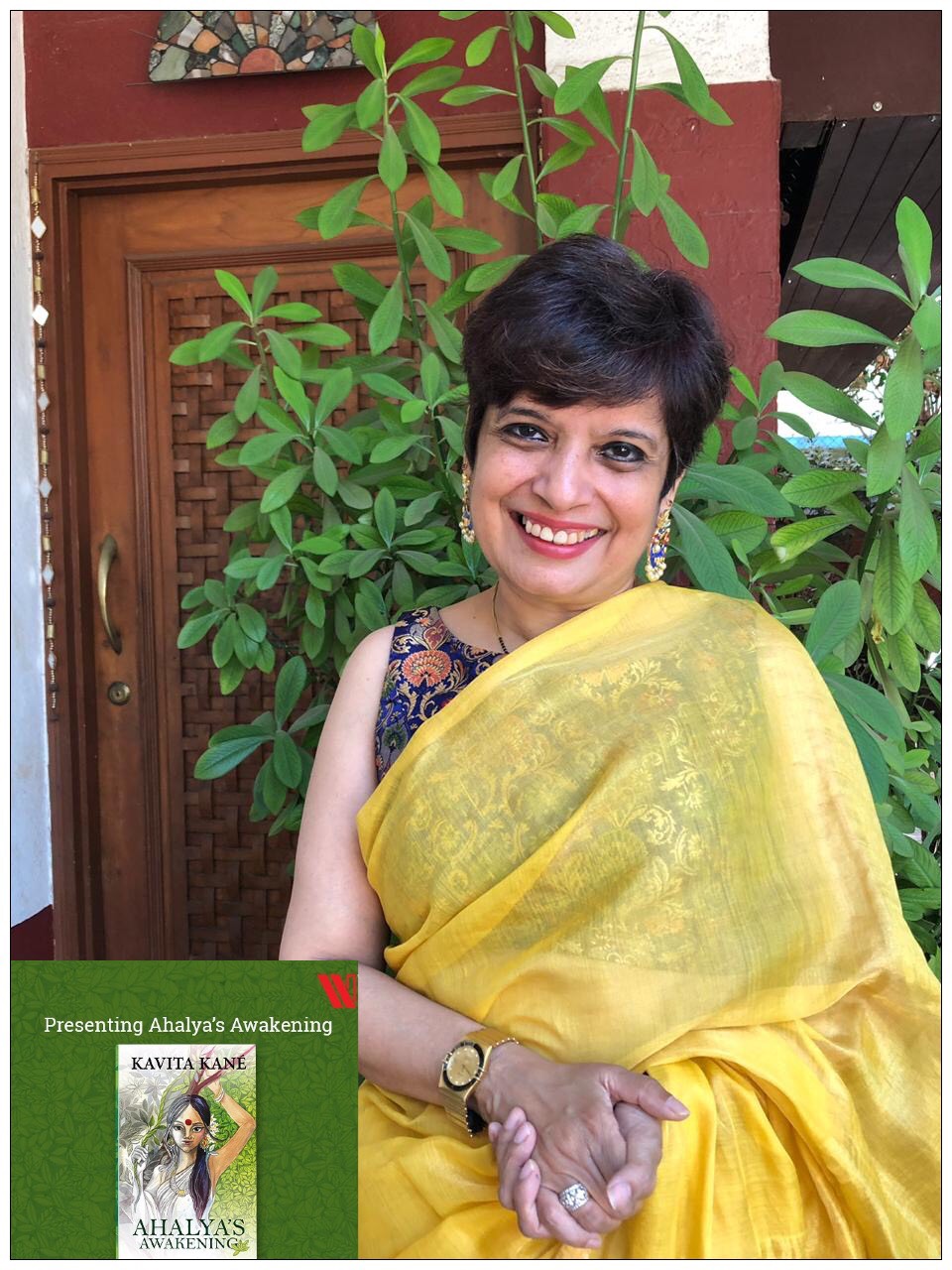

“I respect my readers as much as they respect me. I think readers are often underestimated. They are mature and discerning enough to know the blurring lines of fact, fiction and falsity; of what mythological fiction means and entails. Likewise, the author has to be as responsible,” says the bestselling author of many works including The Karna’s Wife: The Outcast’s Queen, Sita’s Sister, Menaka’s Choice, Lanka’s Princess and The Fisher Queen’s Dynasty.

It is perhaps a reaffirming of the universality and profundity of Indian philosophical and civilizational thought, that one can easily identify with the characters and their dilemmas. While “You can’t measure those times with today’s mores and current definitions, but what is contemporary is the universal emotions of love and loyalty, rivalry and jealousy, grief and forgiveness, rage, revenge and redemption – all those human conflicts and the struggle of Man within and outside. That is what makes the epics so immediately and immensely identifiable,” says Kané.

In Ahalya’s Awakening, Kané’s Ahalya story is “not just about Rishi Gautam who cursed his wife Ahalya and turned her into a stone for her infidelity. Nor is it just about Ahalya the woman turned into a stone to be later freed from the curse, by Rama. That would be too simple, even erroneous if seen through myopic or misogynistic eyes. This small episode, seemingly a mere mention – has huge impact in the later narrative of the epic, almost like a precursor to what is to come – and become of the protagonist Sita. The complexity and depth of marital relationships and adultery are inexorably layered. This brief incident should be seen in its larger implications, emphasizing its relevance in society caught in conflict of not just adultery and loyalty, but of justice and the act of judging and judgement and being judgemental.”

By sticking to the original, that Kané manages to avoid the pitfalls of modern translators of portraying women as victims. “It’s not modern translators but gradually through the centuries the original text itself became a victim of patriarchy. Check the original stories of Ahalya and Shakuntala and how with changing society norms and situations, they got reduced to helpless victims. Valmiki’s Ahalya is a woman who knows what she wants and desires revealing the entire gamut of emotions and experience but that same Ahalya becomes a voiceless victim bracketed either as the devoted wife or the adulteress, painted white or black. Her status and subordination has swung in extremes through social times, through changed perspectives.”

Kané’s books are women-centric but for her feminism is not being ‘anti-men or anti-family but about speaking out against patriarchy. “Feminism is about seeing the woman as a ‘person’ entitled to equal opportunity and prerogative and dignity of living as an independent individual.”

Since India’s great epics have been written by men, one does wonder how a woman would have written them. “We even see the texts through the men’s eyes! One could dismiss this again conclusively on patriarchy, but then there were remarkable women who broke the mould. Just as there are all these remarkable women in the epics – be it Draupadi, Satyavati, Kunti , Devyani, Gandhari or Ahalya, Sita, Mandodari, Tara in the Ramayana, we have had women voices with writers like Velliveethiyar, Ponmudiyar, Andal Godadevi, Avvaiyar, the Brahmavadinis like Lopamudra, Gargi Vachaknavi, Ghosha and Maitreyi.”

In an earlier interview, Kané has said she is more interested in the women characters because she thinks they are more layered. “They don’t just multi-task but multi-think too—they are a mother, daughter, sister, friend, wife and so many other roles all at the same time. So I feel thinking is a continuous and dynamic process for women. They are more complex and more intricate. Also I try to make the female characters more identifiable in my stories and being a woman, it is easier for me to do so.”

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.