INDICA is proposing to organise a conference on “Hinduism & Environmentalism” to join the global efforts being made to repair our environment and save the Earth.

The conference is aimed at highlighting the potential of all the components of the Hindu cultural complex for the resolution of the present ecological crisis, leading to a healthy eco-friendly life and to the prosperity of humans through the prosperity of nature and the Earth.

The contemporary model of balance between conservation and development does not oppose the use of technology, which often interferes with nature and its processes through man-made tools and techniques. But technology can be used in an eco-friendly way, so that interference with nature is limited and in a manner that avoids ecological imbalance.

The Hindu worldview, as found in its texts, and in the culture reflected in those texts, has a similar combination of, and balance between passion & compassion, violence & non-violence, conservation & prosperity.

Hindu texts—such as Itihasa, the Puranas and Kavyas—describe a diverse social life where Rishis or sages lived a life of compassion very similar to the permaculture of Fukuoka. The rest of society is described as living a life of passion, but with the ideal of living with Dharma, the nature-sustaining principle (etymologically that which holds, sustains). They passionately pursue prosperity, but only through the path of conservation. Rishis lived the life of non-violence. The Kshatriyas, the warrior class, lived the life of violence intended to save the vulnerable from being harmed by the cruel and the unethical and to save nature from the violence committed by those lacking respect for it. Passionate society respected the compassionate Rishis, and the compassionate Rishis instructed them in Dharma, the nature-sustaining principle. The violent warrior class respected the non-violent Rishis, and the non-violent Rishis instructed them to use their violence to protect the vulnerable. Neither demanded nor expected the other to live their lifestyle. In contemporary parlance, it can be said that these texts depict a society where the Permaculture community and the community pursuing Sustainable Development live side by side, with mutual love and respect.

The Hindu texts also offer praise to multiple divinities, these divinities being both immanent or active in nature and irreducible to it. A distinctive aspect of the tradition of the Hindus was the Yajnas, the fire-mediated sacred procedures through which they interacted with their divinities. Though the Indic folk and tribal traditions have different kinds of sacred procedures, such as worshipping their divinities through offerings to images, it is probably the common environmentalist worldview that led to a harmonious intercultural interaction among the Vedic and the Indic folk and tribal traditions, bringing forth a Puranic-Agamic culture, a syncretism of the Vedic with the folk and the tribal traditions.

It is this cultural complex that includes Puranic and Agamic culture with multiple diverse sub-traditions, the individual cultures of the Vedic and the Indic folk and tribal traditions, that is called ‘Hinduism’ today.

Another distinctive aspect of the Hindu tradition is that it has very ancient texts that clearly articulate its environmentalist worldview in an explanatory way.

For example, the Bhagavadgita, an ancient Hindu text held in high esteem for being among the most central texts of the entire Hindu cultural complex, describes the mutual relationship between nature and humans, not as that of domination, but of friendship, and says,

sahayajñāḥprajāḥsr̥ṣṭvāpurōvācaprajāpatiḥ |

anēnaprasaviṣyadhvamēṣavō’stviṣṭakāmadhuk || 3-10||

dēvānbhāvayatānēnatēdēvābhāvayantuvaḥ |

parasparaṁbhāvayantaḥśrēyaḥparamavāpsyatha || 3-11||

iṣṭānbhōgānhivōdēvādāsyantēyajñabhāvitāḥ |

tairdattānapradāyaibhyōyōbhuṅktēstēnaēvasaḥ || 3-12||

Prajāpati, the creator, in the beginning created human beings along with the Yajnas, the fire-mediated sacred procedures (eco-friendly/nature nourishing/sacrificial procedures), and said, “through these procedures get what you want; these fulfil whatever you want. Through these procedures, nourish and nurture the devas (divinities) and they shall nourish and nurture you back. Treating each other thus, may you, the humans, and the Gods both achieve the greatest well-being. Luxuries and pleasures that you want are provided by the devas, who in turn enjoy your Yajnas.”

Though the word Yajna was originally used only in the sense of the fire-mediated nature-nourishing sacred procedures, gradually it acquired a semantic expansion to refer to any nature-sustaining activity involving organismic organization (yaj = to organize) of sacrificial (= selflessly giving) activities.

In the same context, a few verses later, the book even talks of following the ‘cycle’, a concept that is so frequently found in contemporary ecological literature, and says,

ēvaṁpravartitaṁcakraṁnānuvartayatīhayaḥ |

aghāyurindriyārāmōmōghaṁpārthasajīvati || 3-16||

one who does not live according to (the principles of) the cycle (as described in the previous verses) is a sinful creature and lives a vain life.

The idea of cycle is central to the Hindu cosmology, starting from the description of ‘Creation’ in the Vedic hymn to the (Cosmic) Person, and connected with the concepts of cosmic cyclic time scales in the Puranas.

Mircea Eliade, a founder of the discipline of Religious Studies, in his book The Myth of the Eternal Return (1954), highlights the distinction of this view in cultures like the Hindu:

The essential theme of my investigation bears on the image of himself formed by the man of the archaic societies and on the place that he assumes in the Cosmos. The chief difference between the man of the archaic and traditional societies and the man of the modern societies with their strong imprint of Judaeo-Christianity lies in the fact that the former feels himself indissolubly connected with the Cosmos and the cosmic rhythms, whereas the latter insists that he is connected only with History.

Eliade’s book is a critique of the ‘tyranny’ of ‘History’ which he says is rooted in the ‘Linear Time’ of Judeo-Christian tradition rather than the ‘Cyclic Time’ believed in by traditional societies.

The Puranas (collections of sacred narratives and sacred instructions) of the Hindu cultural complex have a triad of supreme divinities for the creative, sustaining, and dissolving powers of the cosmos. In each cosmic cycle, a monstrous power arrogantly captures the natural forces, such as fire, wind, light, etc., and dominates and tyrannizes them (exhibiting the attitude of nature-controlling science and technology), torturing the performers of sacred procedures meant to nourish nature, and tormenting those who are dedicated to the sustaining power.

At each such instance, the sustaining power manifests itself on Earth in some form or other, destroys the destructive force, and restores the cosmos/nature to its prosperity.

Vedic texts such as the Bhagavadgita clearly articulate the theory behind such narratives, saying that whenever Dharma, the nature-sustaining principle, is harmed or damaged, the sustaining force manifests itself and restores Dharma, the nature-sustaining principle.

Another aspect of the environmentalism inherent in the Hindu cultural complex resembles a strand of the contemporary environmentalist movement called ecofeminism.

In their 1993 essay, “Ecofeminism: Toward Global Justice and Planetary Health”, Greta Gaard and Lori Gruen outline what they call the “ecofeminist framework” which holds the rise of patriarchal religions and their establishment of gender hierarchies, along with their denial of immanent divinity, responsible for the present ecological crisis.

But in the Hindu worldview, the sustaining power mentioned above is viewed in a feminine form too, and the Earth, for example, is viewed as a feminine divinity, Bhūdēvī.

In the Hindu folk and tribal traditions, there are a large number of feminine divinities, many of them associated with diverse plants and animals, features of the natural landscape, bodies of water etc., and the fertility of these.

There is also a tradition of village Goddesses who embody and sustain the entire village ecosystem, as tribal societies engage with the forest ecosystem through the Goddesses associated with that landscape. Epidemics and natural calamities are viewed as these deities’ malevolent aspect, the greenery and prosperity of nature as their benevolent aspect.

This is another element the Vedic tradition and the Indic folk and tribal traditions have in common. The concept of dēvī, the feminine divine, is found in the Vedas themselves.

The Puranas have the supreme power of sustenance in a feminine form. In these narratives, the supreme feminine power of sustenance manifests in several different forms to defeat aggressors against the environment/nature.

There is a whole Purana called Dēvībhāgavatam dedicated to this supreme feminine power of sustenance, also known by the name śakti, the Power. A number of spiritual traditions— śāktēya, tantra, śrīvidyā, etc.—developed around this supreme feminine divine.

The Puranic-Agamic culture, along with the folk & tribal traditions that contributed to it, accords a major role to this Devi/Shakti. Hindu folk and tribal traditions view their local Goddesses as embodying that all-pervading supreme feminine divine. There is significant explanatory literature in the Hindu tradition explaining this ecofeminism in the Vedas, Puranas, and the common Hindu cultural complex.

The explanatory literature of the Hindu tradition almost always shares the spirit of Deep Ecology, another contemporary trend in environmentalism. The hymn to the Cosmic Person in the Vedas is a celebration of the intricate organismic interconnection and interdependence among all parts of the cosmos that contemporary Deep Ecology advocates.

In this system of thought, every ecosystem, as a self-regulating and self-sustaining system, is called purusha, ‘person’, and the source of the self-organization of such a system is given the name ātman, ‘self’. Humans in the explanatory literature of the Indic tradition are almost always viewed as part of the system of bhūtāni, beings.

Interconnections and continuities among all bhūtāni, beings, jaḍa, the inanimate/non-conscious and the animate/conscious, are discussed through several detailed theoretical frameworks.

One such framework is that of the cosmos as Yajna, a process similar to the fire-mediated sacred procedures, a unifying organization of life-generating contributions from all beings. The cosmos is described as the Yajna that subsumes sub-yajnas, and Yajna itself is described as performed by natural forces.

The Upanishads are Vedic texts discussing concepts such as ātman (self), Brahman, the imperishable essence manifest as cosmos, also known as paramātman (parama + ātman), that is, the self of the cosmic ecosystem. These texts speak through the all-pervading nature of the divine with respect to the cosmos.

The key concepts of these texts—such as jīva (individual self), jagat (the world), īśvara (the world-administering principle), brahman/paramātman—are explained as intricately connected, through ideas such as brahman and/or īśvara permeating the jagat and jīvas, or brahman and/or īśvara being made up of a combination of jīvas, or jīva as the limited expression of brahman/paramātman.

Thus, all these Hindu texts articulated Deep Ecology in a deep & intricate way.

Call For Papers

We invite practitioners, scholars, researchers, and activists to present this unique perspective on Environmentalism as envisioned in our Hindu traditions.

The Conference will be curated by Sri Nagaraj Paturi, Senior Director INDICA.

Suggested topics:

- Nature aesthetic-spirituality in Veda mantras.

- Veda mantras instructing against violence to earth and nature.

- Deva-asura conflict in Veda mantras and Puranas as an environmentalist idea.

- Worship of nature in Hindu folk and tribal culture.

- Animism, pantheism, and other common environmentalist aspects in Vedic, folk, and tribal Hinduism.

- Fertility rituals shared by Vedic, folk, and tribal Hinduism.

- Hindu equanimous negotiation with malevolence with benevolence of nature through festivals and rituals in Vedic (including Puranic-Agamic), folk and tribal traditions

- Dharma as an environmentalist idea.

- Yajna as environmentalist.

- War and anti-war, violence and non-violence environmentalism in Mahabharata and other Hindu scriptures.

- Feminine divine as Hindu environmentalist tradition.

- Sacred Groves as Hindu environmentalism.

- Environmentalist aspects of Hindu Architecture including Temple Architecture.

- Worship of landscape, plants and trees and animals in Hindu Vedic, folk, and tribal traditions.

Submissions:

Abstracts of 300 words (font size 12, Times New Roman, 1.5 line spacing) must be sent by email to namaste@indica.org.in by 11th January with the title of the Conference mentioned in the subject. Accepted abstracts will be immediately notified and the final paper should be submitted by 31st January.

Abstracts should provide a brief description of the topic and, if required, the theoretical focus, objectives, study area, and research methodology. Acceptance of the abstract will be notified to the author.

The Conference is scheduled for 11th and 12th February 2022.

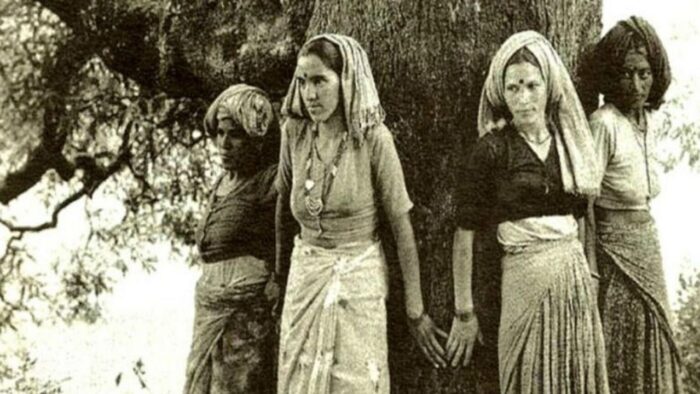

Location of the Conference: We propose holding the Conference at Jodhpur, Rajasthan. A half-day trip to Khejrali to pay homage to Amrita Devi is also planned.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.