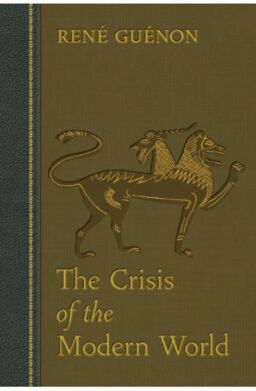

(This is a three-part summary of a captivating book by the French philosopher René Guénon. It critiques modernity through the lens of tradition, maintaining as much relevance today as it did when first published in 1923. Aside from the introduction, the remainder of the article belongs solely to René Guénon. This piece serves as a stepping stone for readers to visit Guénon’s extensive writings, which cover a wide range of topics, including Hindu philosophy. He emerged as a staunch defender of Eastern traditions in a world increasingly affected by the repercussions of Western modernity.)

Introduction: René Guénon (1886-1951)

Metaphysics is the study of the absolute first principles and the highest truths. It examines the single Reality and the Unity from which the multiplicity of the world emerges. In contrast, science begins and remains within the realm of multiplicity. Philosophy seeks to comprehend these first principles by exploring the diverse manifestations of the world, but modern Western philosophy often becomes ensnared in the external world and rarely arrives at the ultimate truth.

In Hindu traditions, the highest metaphysical principle is known as “Brahman”. Attaining knowledge of this principle, referred to as “moksha”, is regarded as the ultimate goal for both individuals and society, as expressed by our sages and seers. Knowledge can be acquired through three means: instinct (as observed in animals), reason (characteristic of humans), and intuition (exhibited by yogis and rishis). It is the last form of knowledge that leads to an understanding of the highest principles and constitutes the essence of metaphysics. This intuitive access to knowledge is central to Vedanta and is a recurring theme among thinkers belonging to the school called “Perennial philosophy” such as Ananda Coomaraswamy, Frithjof Schuon, and René Guénon.

We should exercise caution when using the term “intuition”, as it may be misinterpreted as a form of “sixth sense” in which reason plays no role. A more appropriate term for intuition would be “higher reason”, as the truths it infers arise from the reasoning faculty itself when it is pure and unencumbered by internal dispositions. The purified intellect and these dispositions are referred to as “shuddha-buddhi” and “vasanas” respectively in Indian texts or shastras. The subjects addressed by higher reason extend beyond the sensory realm; thus, its inferential reasoning does not merely connect two observable phenomena, such as fire and smoke. Rather, it signifies a vyapti (inference) that associates two entities, one or both of which may be non-perceptible. However, this topic exceeds the scope of the present article.

Guénon, although relatively obscure, is a significant figure in metaphysics. Born a French Catholic, he later converted to Islam and settled in Egypt, where he eventually passed away. The essential unity perceived by perennial philosophers among various world religions—such as Islam (particularly Sufism), Christianity, Buddhism, and Hinduism—can be challenging to grasp. Frithjof Schuon posits that an absolute unity exists at an esoteric level that surpasses human reason.

Guénon wrote extensively on a wide range of topics, including Vedanta and Hindu doctrines. His seminal work, The Crisis of the Modern World, offers an analysis of the modern world through the lens of tradition. Written in 1923, this book is remarkably prescient about the potential and catastrophic dangers associated with modernity. At the time of its writing, the First World War had concluded, while the even more devastating Second World War had yet to take place. The smartphones were far from being conceived. Nevertheless, Guénon accurately describes the trajectory of modern science. He identifies the most significant perils of modernity as individualism and nationalism, which ultimately contribute to disruption across the globe and will increase in the days to come.

This book is essential reading for anyone intrigued by the marvels of modernity, science, and the complex philosophy that often raises more questions than it answers. The three-part series serves as a summary and paraphrase of the book itself, designed solely for those interested in exploring René Guénon’s universe more deeply. In a world marked by significant disruption and disunity, we must critically examine the effectiveness of concepts like individualism, nationalism, democracy, the power of numbers, scientific progress, and even philosophy. These ideas may ultimately lead to the eventual collapse of society unless we return to the fundamental principles that have remained intact in Eastern traditions, such as Vedanta. The author is unequivocal in stating that the only hope for a world in decline lies within tradition. This is the central message of the insightful book by René Guénon.

The Dark Age

Higher truths are becoming increasingly obscure in the current age of Kali, also known as the “dark age”, making their discovery challenging. A progressive materialisation increasingly separates us from the principle of pure spirituality or ultimate reality. Nevertheless, subtle symbols abound, indicating what has been lost. A new cycle commences when that which was concealed re-emerges into visibility. This cyclic development, occurring in a downward trajectory, stands in stark contrast to the notion of a linear “progress” as understood by modern society.

Two opposing tendencies manifest in phases of existence: descending and ascending, or centrifugal and centripetal. One represents a move away from the highest principle, while the other signifies a return to it. These two tendencies operate simultaneously, albeit in varying degrees, to restore a certain equilibrium as circumstances permit. Additionally, secondary phases reflect the laws of the greater cycle on a smaller scale.

A significant recent period in human history is the “historical” (accessible or “profane”) era, the latter part of which is referred to as the “modern” age. This historical period dates back to the sixth century BCE according to modern scholars and historians; beyond this point, chronology purportedly becomes vague and falls into the realm of “legendary.” China has annals that document much earlier periods, yet contemporary writers categorise these times as “legendary”. The so-called “classical” antiquity, spanning from the 8th century BCE to the 6th century CE, represents a relative antiquity that is, in fact, closer to the modern age than the genuine antiquity of the Manavantaras as outlined in Hindu teachings. The earlier legendary periods are dismissed as unworthy of consideration due to a prevailing contempt for tradition.

The sixth century BCE is an important epoch that witnessed significant transformations across various regions. In China, Taoism and Confucianism emerged. In India, Buddhism gained prominence. The absence of monuments in India predating this period is often a proof by Orientalists to attribute the origins of all things to Buddhism, thus exaggerating its importance. However, the straightforward explanation is that earlier constructions, primarily made of wood, left no lasting traces. To the west, the Jewish people were emerging from Babylonian captivity. For Rome and Greece, the sixth century marked the inception of the so-called “classical” and “historical” civilisations, despite archaeological evidence indicating a clear pre-existing civilisation.

During this time, a distinct form of thought known as “philosophy” emerged, which had a detrimental effect on the entire Western world. Etymologically, it denotes “love of wisdom” and suggests an initial inclination towards wisdom leading to knowledge. Ironically, “philosophy” itself became equated with wisdom, transforming the means into an end. The result was a “profane” philosophy, a feigned wisdom that was purely human and rational, replacing the true, traditional, supra-rational, and “non-human” wisdom.

However, something of this true wisdom persisted throughout antiquity, as evidenced primarily by the endurance of the “mysteries”. The “profane” philosophy rejected all forms of esoterism associated with higher perspectives, which ultimately contributed to the emergence of the modern world. A distinctly modern attitude, characterised by rationalism, took shape. The modern world rightly claims to be a continuation of Greco-Latin civilisation in this placing of reason at the highest level.

Christianity, marking another pivotal period, signified a complete rupture from antiquity. This transition coincided with both the dispersal of the Jews and the final phase of Greco-Latin civilisation. The ascendancy of purely “profane” philosophy led to a decline in true intellectuality, while the ancient sacred doctrines deteriorated into “paganism” and superstitions. Following a barbaric destruction of the old order, a new normal order of the Middle Ages (from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries CE) was established. However, the true Middle Ages extend from the reign of Charlemagne (8th century CE) to the dawn of the fourteenth century, at which point a new decadence began to gather momentum. This date marks the actual beginning of the modern crisis: the onset of the disruption of Christendom, the rise of “nations”, and the decline of the feudal system.

The Renaissance and Reformation primarily emerged as consequences of the preceding decadence, representing a definitive break with the traditional spirit—the former in arts and sciences and the latter in religion itself. While claiming to revive Greco-Latin civilisations, the Renaissance appropriated only their superficial aspects (the written forms) and assumed an artificial character. From this point forward, there existed only “profane” philosophy and “profane” science. This was a negation of true intellectuality, reducing knowledge to its most rudimentary form: the empirical and analytical study of facts detached from principles. Such an approach resulted in a disarray of countless insignificant details, unfounded and mutually contradictory hypotheses, and fragmented perspectives that led to practical applications, which constitute the sole genuine superiority of modern civilisation.

“Humanism” emerged to honour the Renaissance, encapsulating the entire agenda of modern civilisation. By reducing everything to purely human proportions, humanism eradicated every principle of a higher order under the guise of conquering the Earth. Humanism represented the first manifestation of contemporary secularism. The measure of man as an end in itself progressively degraded modern civilisation, leading it to focus on satisfying the material aspects of human nature while perpetually generating more artificial needs than it could fulfil.

What is the reason for this modernity? According to Far Eastern traditions, the present age, despite its inherent pain, holds a specific place within the broader course of human development. The “disordered” state, when viewed from a particular perspective, is nonetheless a consequence of a higher law. Consequently, as true intellectuality fades, individuals tend to exploit material matters to an ever-greater extent, becoming more enslaved in the process. They condemn themselves to a state of perpetual agitation, lacking direction or objectives, resulting in a dispersion characterised by pure multiplicity that ultimately leads to dissolution. This, in broad terms, serves as the true explanation of the modern world.

While it is possible for virtue to emerge from evil, it remains, at its core, evil. Modern civilisation undoubtedly has a rationale for its existence; even if it signifies a pivotal moment that concludes a cycle, it still warrants scrutiny.

The Opposition between the East and the West

There is a gulf between East and West in the modern world. An equivalence between civilisations with different forms can exist if they are based on the same fundamental principles and when the differences are merely outward and superficial. An abnormal civilisation not recognising or even denying higher principles from above cannot have a mutual understanding with other civilisations. Today, Eastern civilisations have remained faithful to the traditional viewpoint, and the modern West, represented by Europe and America, has become an anti-traditional civilisation.

The common features that characterise traditional civilisations are absent in the West. Chinese civilisation epitomises the Far East; Hindu culture represents the Middle East (specifically, India), and Islamic societies denote the Near East. The Near East, which occupies an intermediate position, shares characteristics with the Western civilisation as it existed during the Middle Ages but opposes the modern West, much like the Eastern civilisations do.

The mediaeval period in the West was predominantly traditional. A transformation in recent centuries, emerging solely from the West, has rendered it both modern and anti-traditional. The Eastern mentality can be considered normal, as this perspective was once prevalent in both East and West. Normality also suggests that it has influenced all cultures, with the exception of contemporary Western civilisations. A more primordial tradition may have underpinned both Western and Eastern traditions, yet at present, only the East embodies the true traditional spirit.

Some individuals in the modern West are seeking a return to tradition in various forms. However, these endeavours often suffer from a lack of clarity, mental confusion, and the emergence of pseudo-traditions devoid of foundational principles. The contrived notion of a “Western tradition” is as incongruous as the equally fictitious “Eastern tradition” proposed by the Theosophists. While there are remnants of traditional civilisation among the Celts, the components that make up “Celtism” do not amount to a cohesive or complete tradition.

Only by establishing contact with the East’s still-living traditions can we bring what is capable of revival back to life. The East can offer this invaluable service to the West. The claims regarding Druid traditions being preserved in their entirety lack sufficient evidence. In reality, Christianity absorbed the surviving Celtic elements during the Middle Ages; the legend of the Holy Grail serves as a notable example. The reconstruction of Western tradition could only occur if it takes a religious form, which must be Christian and specifically Catholic. However, Christianity is no longer comprehended in its deeper significance, despite its potential to serve as a foundation for a return to these traditions.

The most viable means of restoring the traditions of the Middle Ages would likely be the efforts of a strongly established intellectual elite. The majority may remain unaware of Eastern doctrines, yet still receive meaningful influence from this elite. Nonetheless, the West’s, and particularly Christianity’s, perspective towards the East is predominantly one of hostility. Both Christianity and Eastern doctrines articulate many concepts in similar terms, but this prevailing hostility often conveys opposing meanings.

In the current state of mental confusion, the terms “tradition” and “religion” are often used interchangeably. However, tradition should not be applied as a label to anything that is purely of human origin. Specifically, philosophy does not merit this designation, as it is entirely rooted in rational thought. Thus, it is essentially “profane”. The lost tradition can only be revived through a connection with the living traditional spirit, which remains vibrantly alive only in the East.

The primary requirement for the West is to aspire towards a return to a traditional perspective. Although the various “anti-modern” movements are incomplete, they are commendable in their critical approach. Nevertheless, these movements thrive only within limited confines. There remains hope because Westerners are no longer united in their wholesome acceptance of the exclusively materialistic trajectory of modern civilisation. If the West regains its tradition, it will likely lead to a better understanding with the East.

The traditional outlook remains fundamentally consistent across all contexts, regardless of its outward manifestation, adapting to various mental conditions and the specific circumstances of time and place. Only those who can adopt a truly intellectual perspective can grasp the essential unity beneath apparent multiplicity. Understanding principles constitutes fundamental knowledge, often referred to as metaphysical knowledge. This knowledge is as universal as the principles themselves. Once we accomplish this foundational work, we can further develop its effects, leading to consensus in all other areas.

A true understanding can only be attained from a higher vantage point, rather than from below. This approach should be understood in two ways: the work must commence from the highest level, that is, from principles, and then gradually descend to the various orders of application. Furthermore, this work must exclusively involve an intellectual elite. Embracing tradition would not only foster harmony with the East but also make the West a normal and complete civilisation. To be resolutely “anti-modern” or traditional does not equate to being “anti-Western”; rather, it signifies an effort to rescue the West from its confusion.

The idea of defending the West, as some propose, is surprising because it is the modern West that threatens to engulf all of humanity in the turmoil of its own chaotic activities. This viewpoint is equally peculiar and unwarranted if it implies a defence against the East, as the true East seeks no dominance over anyone, desiring only independence and tranquilly—surely not an unreasonable aspiration. Indeed, the West requires urgent defence, but this defence should be directed towards itself and its inclinations, which, if pursued logically, will ultimately lead to its downfall and destruction.

Knowledge and Action

Traditional Eastern and anti-traditional Western mentalities diverge in their perspectives on the relative significance of contemplation and action. Are these contrary, complementary, or hierarchical, with one subordinating the other? Each may align with a specific order of reality. From a more superficial standpoint, one might regard the two as opposing. However, the reality is that these represent two tendencies, with one or the other prevailing at any given moment.

A more elevated viewpoint transcends the oppositions found at a lower level. Opposition or disharmony can only arise from a specific and limited perspective. Nevertheless, these two facets complement and support one another, forming the dual activities of inward and outward engagement for both individuals and humanity as a whole. Focusing exclusively on one aspect will enhance its development, but it is necessary to consider each person’s unique capacity and nature.

Contemplation is more widely cultivated in the East, particularly in India, while the propensity for action is more pronounced among Western peoples. In the West, contemplation has traditionally been the domain of a much narrower elite. Nevertheless, during the Middle Ages, Western thinkers acknowledged the superiority of contemplation, or pure intelligence. The modern West seems to have lost this recognition, either through a decline in intellectuality or by prioritising action above all else. In this context, the East could assist the West (provided the West is receptive) in rediscovering the significance of its lost traditions. Eastern doctrines, while asserting the primacy of contemplation over action, still grant action its rightful place.

Action, as a fleeting modification of being, cannot possess its higher principle and sufficient reason independently. This principle can only be discerned in contemplation, which equates to knowledge. It is impossible to disentangle knowledge from the method by which it is acquired. Likewise, change cannot occur without an inherently unchanging principle. Aristotle posited the existence of this “unmoved mover” as the origin of all things. In this regard, knowledge functions as the “unmoved mover” of action. Thus, action is situated within the realm of change and “becoming.”

Modern Westerners acknowledge no form of knowledge beyond rational or discursive understanding, which is inherently a reflected knowledge—indirect and imperfect. This lower form of knowledge serves immediate practical purposes. However, in the absence of a higher principle, it devolves into a ceaseless agitation, a defining characteristic of the modern era. Such knowledge is scattered across multiplicity, lacking unification through any overarching principle. In both daily life and scientific thought, one encounters extreme analysis, endless subdivision, strife, conflicts, and a genuine disintegration. Matter embodies multiplicity and division. As one ascends towards pure spirituality, one draws closer to the unity realised through the consciousness of universal principles.

Movement and change exist for their own sake. Their limit is a state of pure disequilibrium, coinciding with the ultimate dissolution of this world. In the speculative realm of science, there is a rapid succession of unfounded theories and hypotheses, leading to a monstrous accumulation of details that signify nothing. Applied science achieves tangible results in the material domain, the only area where modern man can truly claim superiority. Mechanical and industrial inventions will likely continue to proliferate and may ultimately become the primary agents of catastrophe.

In today’s unstable world, a correspondence exists between a realm defined by constant “becoming” and the minds of individuals who perceive all reality as this “becoming”. This perspective negates any genuine knowledge of both higher and even relative orders. The relative cannot be comprehended without the absolute; change is unintelligible without the unchanging; and multiplicity cannot manifest without unity. “Relativism” is inherently contradictory, for in attempting to reduce everything to change, one ultimately denies the very existence of change itself—a notion echoed in the famous arguments of Zeno of Elea.

Even in India, Buddhism formulated a similar concept of the “dissolubility of all things”. Although these theories represent exceptions, they were acts of revolt against traditional viewpoints and lacked broader influence. Recently, the notion of “philosophies of becoming” has been refined into a specific form known as “evolutionism”. The relentless flux of sensory experiences cannot serve as a means for acquiring true knowledge; rather, it signifies the dissolution of all potential knowledge.

Intellectual intuition, the sole pathway to metaphysical knowledge, bears no resemblance to the “intuition” referenced by certain contemporary philosophers. The latter relates to the sensible realm and is sub-rational, while the former—pure intelligence—is supra-rational. Modern thinkers do not even entertain the possibility of intellectual intuition. This absence of consideration explains why rationalism emerged only after Descartes, as it is a distinctly modern phenomenon closely linked to individualism. As long as Westerners disregard intellectual intuition, they cannot possess a true tradition, nor can they achieve any meaningful understanding with the East.

…Continued in Part 2

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.