Introduction

Prose Fiction as a literary genre is a highly evolved form. It is one of the important innovations of the Modern times. Life has significantly moved from Poetry to Prose in the Modern times. The Modern ‘Novel or Fiction’ is the most representative form of the Prose. With it, expression moved from the lyric to the narrative. Lyrical metaphors which adorned poetry as beautiful ornaments became pearls spread in the ocean of the Narrative. However, the latter has created its own “Narrative Metaphors”, far more invisible and equally impactful, which now reign supreme. Thus, the modern man is more of a prose/narrative man than a poetical/lyrical man. This has huge implications for every civilization and ought to be the subject of a different paper.

Ancient poetry across the world evolved its own grammar and poetics. Bharatavarsha anchored its poetics centred around the Natyashastra and Alankara-Shastra, deriving inspiration from Vedic poetry. However, principles of Indian Poetics are applicable equally to prose and poetry. The ‘Champoo’ form of literature is a mixed form – a composition of poetry and prose which has emerged from within the same poetics of our Shastra-s. In addition, our stalwarts of Indian literature who wrote in Bharateeya-Bhashas, to their credit, evolved our own narrative form – a mix of ancient Indian poetics, western narrative forms and some innovation to synthesise the two.

However, before we could reflect our poetics onto the Modern Narrative Plane, the west moved leaps and bounds. It has evolved an exclusive Narrative Theory of its own which has come to significantly influence the modern expression. As our innovation in the Bharateeya-Bhashas did not translate itself into a Theory and Practice built on that Theory, the west has also begun to influence our writing. This influence, more visible in Indian writing in English where it started, is now spreading across our Bhashas.

As a result, we have lost our generative capacity to shape our own narrative forms. Our universities now teach western narrative theory. This theory is drawn from the experience of the way the west evolved as a civilization. As a consequence, not just India, societies world over are gradually imbibing a western way of thinking in their narrative construction. Indic Fiction is no exception. There is plenty of literature in western narrative theory that further deepens the access and the evolution of this theory. In recent times, one can see the influence of Joseph Campbell’s work in the novel form [Ref: A Hero with a Thousand Faces – Joseph Campbell].

There is an opportunity to create our own Theory of Narrative drawn from our rich tradition consisting of our Philosophy, Poetics and Performative Traditions. The Modern Novel, a representative form of the prose, can be characterised as a collection of character-journeys in complex engagement with each other. It needs a Bharateeya philosophical foundation from which we can imagine diverse character journeys and engagement. In many ways, such journeys are available in our epics, classical literature and folk literature. However, we need to bring them to the modern forms of novels and short stories.

This paper aims to create a philosophical foundation and a meta universe for the Indic Creative Narrative, drawn from Indian Thought, within which such journeys can be imagined and carved.

The Philosophical Foundation

In the Bharateeya Parampara, the Chaturvidha Purushartha drives one’s life. From the western stand-point, it can be termed as the equivalent of an axiomatic fundamental. All traditional Indian texts have Purushartha as their underpinning. It is often not stated but assumed as an obvious reality. The perspective of Chaturvidha Purushartha and its origins are explained in detail in the paper – Vedic Origins of Sustainability and Environmentalism. This section provides a brief summary as required for this paper. It consists of four elements as given below.

- Kama – The Desire: Every man has the right to fulfil one’s desires.

- Artha – The Wealth for Security: Every man has the right to create wealth to secure one’s life and tradition.

- Dharma – The Balance: Since worldly resources that serve Kama and Artha are limited, one’s Artha and Kama clash against each other. Hence, one must pursue Dharma so that Artha and Kama are sustainable

- Moksha – The Liberation: Every man has the right to pursue a Sacred Path for that alone creates a space for Dharma.

It is referred to as Purushartha as these secure one’s life. We have both a right and a duty to pursue this. In many ways, it operates at a level beyond a right and a duty.

It is important to note that Kama and Artha are subservient to Dharma in this framework. That in our pursuit of security and desire we may run amok and create significant conflict is part of the deep rooted wisdom of Bharateeya Parampara. This has two reasons

- Worldly resources are limited.

- Our pursuit of Artha and Kama are driven by our Arishadvargas – Kama (The Desire), Krodha (Anger), Lobha (Greed), Moha (Attachment), Mada (intoxication – of the mind), Matsarya (The Jealousy).

These six Arishadvargas are considered as our enemies – fundamentally arresting our progress in the path of Moksha. We must recognize two important points in these Arishadvargas.

- Kama is both a Desire that must be pursued as part of the Chaturvidha Purushartha and one that must be dealt with as the Enemy as part of Arishadvarga. That is acknowledged by the Tatva of Dharma. Dharma is that which controls Artha and Kama (because of their susceptibility to the Arishadvarga) and directs them towards striving for Moksha.

- Each of these Arishadvarga-s feed the other and hence their presentation as a collection.

Chaturvidha Purushartha is a framework for one to go about with life. In other words, one’s indulgence in this framework or the abstinence paints one’s journey in life. It’s a complex plane on which our life becomes a multi-dimensional trajectory.

This philosophical perspective is not incidental or accidental, though. It is drawn from the larger trajectory that Bharateeya parampara desires for the collective Universe of life. That is described by the principle of Srishti-Sthiti-Laya, described in detail in all Vedic texts including the Bhagavata. It can be minimally described as given below.

- Bharateeya Parampara desires that The Universe is always in the state of Sthiti.

- Sthiti is defined as that State of the Universe where it is

- Dynamic i.e., seeking a new State

- Yet in Stable Equilibrium

- The Dynamic in Sthiti is referred to as Srishti.

- Universe always being in Sthiti means

- All change in the Universe is through Srishti

- All Srishti is subservient to Sthiti and is successful only when it achieves Sthiti in each of its changes.

- This Dynamic always operates in a Cycle. Everything that is an outcome of Sristhi will have a natural end – ie., Laya.

- Srishti is never perfect. It errs in the path of keeping the Universe in Sthiti.

- Laya performs the task of Dissolution.

- Laya eliminates all whose time has ended.

- Laya results in Pralaya when errs beyond a point.

This worldview is beautifully translated into daily life by the Bharateeya Parampara through the Purushartha. It is drawn from Srishti-Sthiti-Laya in the following manner.

- Moksha of an individual corresponds to Sthiti of the Universe.

- In other words, when one achieves Moksha one increases the Sthiti quotient of the Universe. One moves the Universe closer to the Sthiti.

- While everybody being in the Sthiti is an extraordinary ideal, being in the path of Moksha also results in a proportionate closeness of the Universe of Life to the Sthiti.

- Thus, the Sthiti-Quotient of the Universe represents the extent to which people are on the path of Moksha.

- Dharma is the collective of all actions of all human beings, according to the Natural Order (Rta) that keeps the Universe in Sthiti, thus increasing the Sthiti-Quotient.

- Artha and Kama represent Sristhi. All Srishti on earth are a consequence of the human Artha, Kama. Our Artha, Kama performances are never perfect and have the ability to move the Universe away from Sthiti/Rta. Thus, Srishti errs. However, the extent to which our Artha, Kama is not conformant with the Rta through Dharma determines the extent to which Srishti errs.

This philosophical foundation and framework of human action helps in formulating a Meta-Universe within which human life operates and gets its trajectory in time. It provides a set of principles within which human choices work carving a trajectory in time.

Using this foundation and framework, Modern Creative Literature can paint complex narratives and draw a rich set of characters.

The Meta Universe

A Meta-Universe is that which

- Consists of set of elements and principles operating on those elements

- Using which an infinite number of specific universes can be represented

These principles determine the navigation within that Universe and help us to paint a trajectory of life in time. Theoretically, a Meta-Universe contains within an infinite number of specific universes.

Every creative fiction operates in a specific universe. A Meta-Universe should be potent enough to be able to craft any specific universe. The elements and principles should serve that purpose. Such a specific Universe consists of a definite set of contexts (Vartamana), characters and a distinct movement of time. The Meta-Universe is a collection of all such possible universes i.e., infinite universes articulated through elements and principles.

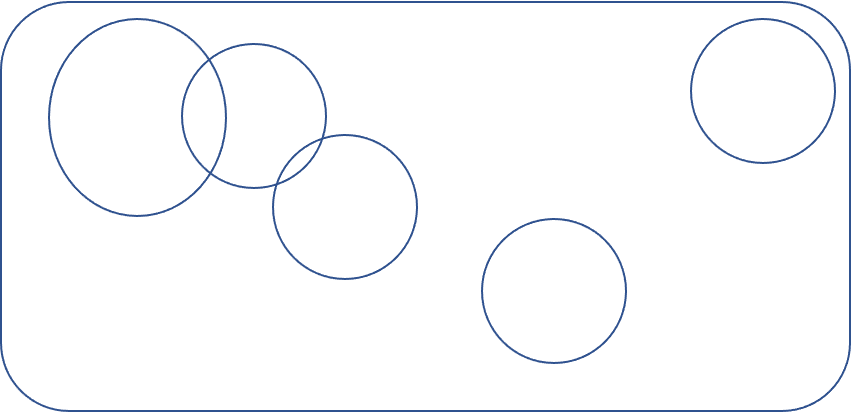

The diagram provided above illustrates the Meta-Universe and the Specific Universes. The outer square is the Meta-Universe that contains an infinite number of Specific Universes.

Meta Universe from Srishti-Sthiti-Laya and Purushartha

Srishti-Sthiti-Laya and Purushartha lead to a Meta-Universe of life that distinguishes itself from other cultures. Here is the Meta-Universe that emerges from the same.

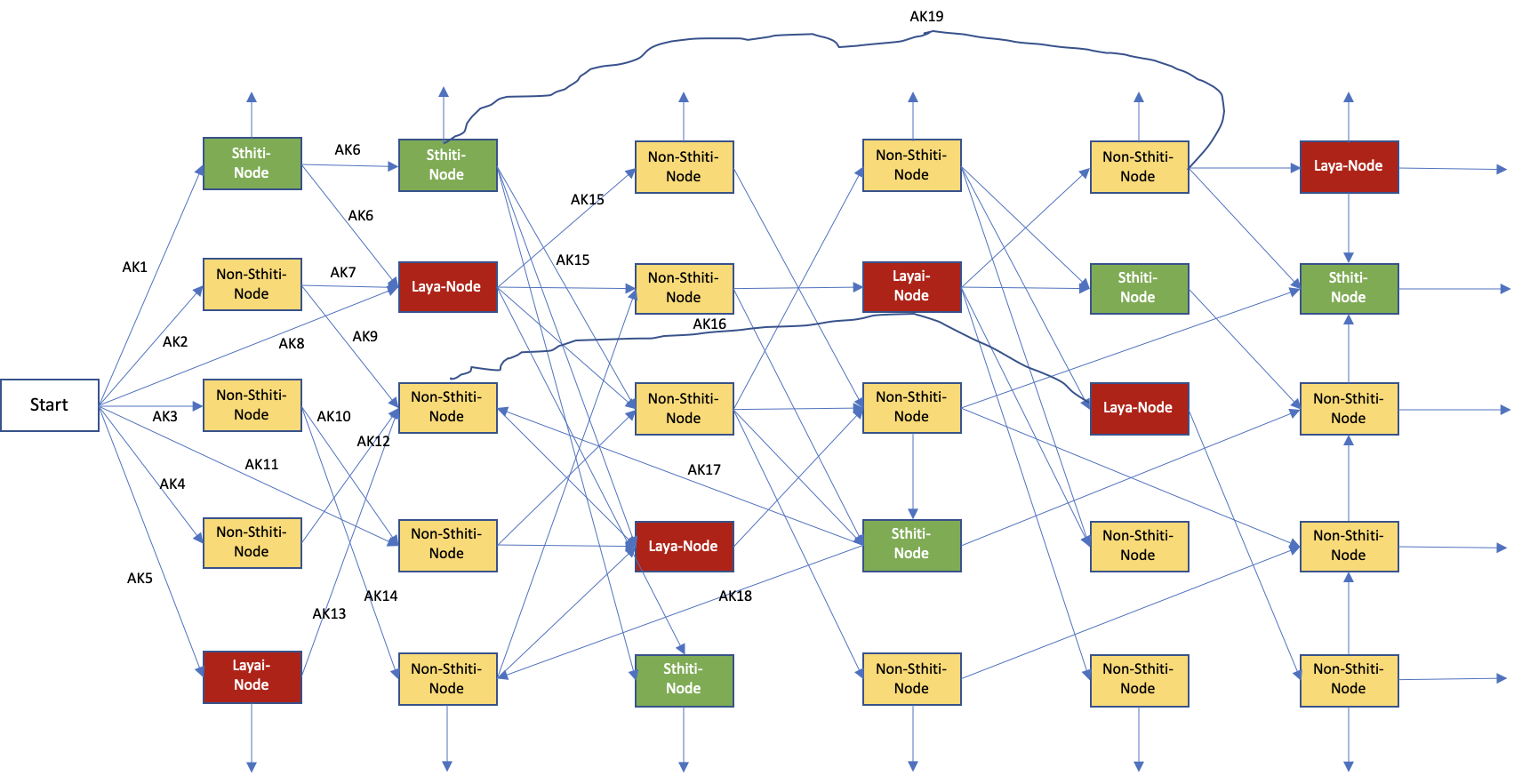

- It is a collection of an infinite number of Nodes.

- Each Node represents life in a specific point in Time – determined by a definite set of Contexts (Vartamaana), Space (Desha) and Time (Kaala).

- Each Node has an attribute that signifies its value within the SSL-Purushartha framework. We refer to it as ‘Sthiti-Quotient’.

- Some Nodes are perfect Nodes where everything in life is in balance, hence they are ‘Sthiti-Nodes’. They have the highest possible ‘Sthiti-Quotient’.

- Other Nodes are ‘Non-Sthiti-Nodes’. They have a lower Sthiti-Quotient and represent an imbalance state.

- Nodes that are highly imbalanced leading to disaster, with very low Sthiti-Quotient, are the ‘Laya-Nodes’.

- Our Artha, Kama actions collectively move the Universe of Life from one Node to another Node.

- Good Artha-Kama actions result in moving towards a Sthiti-Node.

- Conversely, bad Artha-Kama actions result in moving away from a Sthiti-Node.

- The distance of a Non-Sthiti-Node from the nearest Sthiti-Node represents the extent to which the Non-Sthiti-Node is in imbalance.

Life journeys in this Meta-Universe

In the Meta-Universe of SSL-Purushartha consisting of Sthiti-Nodes, Non-Sthiti-Nodes and Laya-Nodes what constitutes an ideal journey of life? A sense of ideal journey determines what is culturally aspired for and becomes a north star. It also helps to draw a rich set of deviations.

- The SSL-Purushartha principles brings the following characteristics to this Meta-Universe

- From most of the Non-Sthiti-Nodes, there are some Sthiti-Nodes, at least, nearby.

- Hence, however bad the Vartamana is, one has a chance to work & move towards a Sthiti-Node.

- But, there are some Non-Sthiti-Nodes, from which a return to a Sthiti-Node is impossible either because of the distance or because of the context (Vartamana) of the node. Such nodes are ‘Laya-Nodes’. In such a case, the trajectory ends – which is Laya.

- When the trajectory of entire masses ends, that is Pralaya. These are disasters.

- The objective of life/ideal journey is to strive to be on a path of Sthiti-Nodes only through our Artha-Kama actions. However, that is nearly impossible. Hence some Madhyama-Marga life-journeys

- Carve a life with maximum number of Sthiti-Nodes

- Carve a life where you at least end your life close to a Sthiti-Node

- Our Artha-Kama actions which move us from one node to another are not perfect.

- We may seek to move towards a Sthiti-Node but you may move away from a Sthiti-Node.

- The objective is not to get back to exactly that Sthiti-Node from which you drifted away. At each node, one seeks to move to the nearest Sthiti-Node. Since, there are many Sthiti-Nodes in this network, one is not frustrated to seek the same destination.

With this vision of life consisting of many Sthiti-Nodes, we have a rich set of ideal life journeys. Completely different life journeys can be ideal at the same time without being the same.

The Application of this Meta-Universe in Creating Writing

How is this Meta-Universe helpful for creative writers? Let us assume a novel/story consisting of different characters.

- Each character starts from a different Desha, Kaala, Vartamana. This defines this Specific Universe.

- Each character strives to maximise the Sthiti-Nodes in their journeys.

- Their Artha-Kama action results in complex clashes – between individuals, communities and so on. Each such action moves them from one Node to another with different Sthiti-Quotients.

A creative narrative then paints the journey of each individual, family, community, state etc., and their Purushartha journey in a specific universe from within this Meta-Universe. These journeys will be a complex result of answering many such questions from the Purushartha framework.

- Kama – What are their Desires, where do they stem from? What actions do they perform? What is the impact on others and the universe? Do they move towards Sthiti or otherwise?

- Artha – What are their needs, securities/insecurities where do they stem from? What actions do they perform? What is the impact on others and the universe? Do they move towards sthiti or otherwise?

- Dharma – How do they rise above their Kama, Artha? What is the balance they strive for? What is the impact? How does it move the collective towards the Sthiti or otherwise?

- Moksha – Who pursues the Sacred Path? What is the impact on the Dharma, Artha, Kama of the self and other entities?

Thus, a Creative Fiction then becomes the journey of individuals and communities operating within the Purushartha framework and striving for a path of Sthiti-Nodes.

For each individual, there is an infinite possibility but the persona of the characters, the limited Artha-Kama actions possible for the characters, their starting Nodes, the limited number of Sthiti-Nodes available and finally the creative imagination of the author determines the actual journey that sums up as the creative work. However, from a plot construction stand-point one can imagine the few critical Sthiti-Nodes and Non-Sthiti-Nodes within which the creative fiction operates and then draw plots.

A Diagrammatic representation of the above world view

What is the journey of the Hero of a Novel

One of the biggest elements of Plot construction is to paint the trajectory of the Hero/Protagonist as that determines the larger trajectory of the work in the modern novels. The rest of the Paper is dedicated to building a framework using which a Hero’s trajectory can be drawn.

The SSL-Purushartha Hero (Nayaka): In this context, it is necessary to list out what a Hero (Nayaka) means from the stand-point of the above framework. At a very high level, the hero/protagonist undertakes an extra-ordinary journey that makes a significant difference to the Self and/or the Family and/or the Community and/or the larger Universe (Rashtra/Vishwa). In other words the hero/protagonist,

- Moves the self from a Lower-Sthiti-Node (where a Sthiti-Node is almost not visible) to a Higher-Sthiti-Node

- Moves the family from a Lower-Sthiti-Node to a Higher-Sthiti-Node

- Moves the community from a Lower-Sthiti-Noder to a Higher-Sthiti-Node

- Moves the larger universe from a Lower-Sthiti-Node to a Higher-Sthiti-Node

The Lower-Sthiti-Node and the Higher-Sthiti-Node are relative in terms of their distance from an absolute Sthiti-Node. This results in different kinds of trajectories.

- If the difference between the two is very high, then the journey is extraordinary.

- If the Lower-Sthiti-Node is a near disaster one then the journey is about a Yugapurusha within the context.

The journey fundamentally is one of the extent of success in moving from a Lower-Sthiti-Node to a Higher-Sthiti-Node.

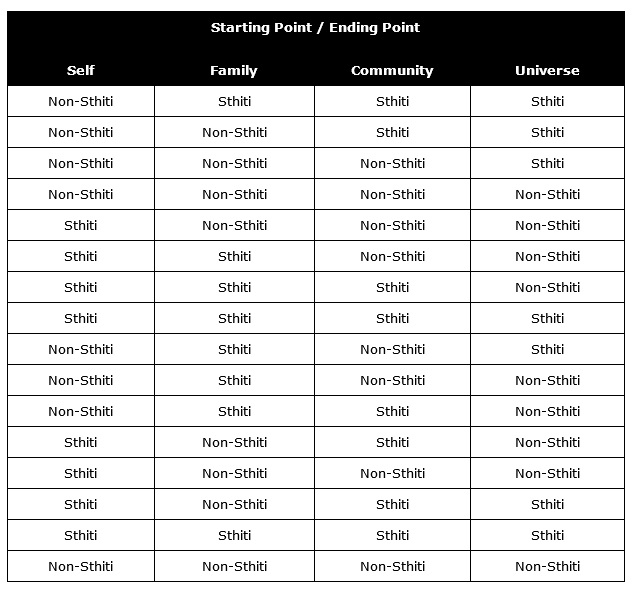

Assuming that the context is determined by the Self, Family, Community and Universe we have 16 Starting Nodes and 16 Ending Nodes as listed in the table below. This essentially means we have 16*16 which is 256 different possibilities just from the Start and End Nodes stand-point.

The world is not ideal though and most will never be in a Sthiti state. Between a Sthiti-State and a Non-Sthiti State it is always a very wide journey. Similarly, the journey between the start and the end state would be one of a series of intermediate states where they would be in one of the above 16 states.

Thus, the creative room is big and wide open for a writer to pick a starting date, determine the series of intermediate states towards an end-date. Around this one builds a set of characters and the Indic philosophies provide a basis to imagine characters with specific Tatvas (Satvika, Rajasa, Tamasa) who have a specific orientation of Artha, Kama resulting in rich possibilities, which we shall be covered in a subsequent paper.

Conclusion:

Finally, any new framework must articulate how it differs from the convention and defend the value proposition.

The SSL-Purushartha framework provides a way of imagining and representing a trajectory of a novel/fiction and its hero differently. However, does it really result in any substantial difference from artistic and cultural stand-points? Here are some differences.

- The focus shifts from merely the hero to that of the hero, family, community and the world.

- Even when it is the individual journey that is portrayed, Desha can never be ignored in the SSL-Purushartha framework and is an important character itself.

- You could potentially have a novel without a protagonist, with many characters and one that depicts many journeys.

- The plot construction gets a richer space with lesser constraints. The start, the middle and the end becomes less important. Conflicts can come at any point in time. The complexity of the Purushartha journey becomes more important.

- The sense of what is ideal gets a different definition. There is a sense of ideal for individuals but it need not be the same for each. As continuity of life is aspired for – the past and the future are constantly present, which in turn provides an opportunity for greater imagination. The Novel/Story itself is released from the clutches of a specific plot of an ideal plot. The Ideal plot is that which paints complex/rich/entertaining Purushartha-journeys and one that engages with human frailties of Arishadvarga.

- Finally, the Sthiti and Moksha dimensions bring entirely different journeys and experiences.

Thus, the SSL-Purushartha framework provides an opportunity to visualise a different universe of life with different character journeys. Apart from being culturally aligned to Bharateeya Parampara, it expands the universe resulting in more diverse journeys and characters. These can already be observed in ancient Indian classics and many modern Bharateeya Bhasha novels.

This paper, though, presents a simpler version of the Indic Creative Narrative that can be drawn from the SSL-Purushartha framework. It further needs to be expanded using the Arishadvargas, Yagna, Tapas, Karma, Satva-Rajas-Tamas so that we create archetypes and apply them to modern contexts.

This paper is a step in that direction.

Feature Image Credit: pinterest.com

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.