Katha Kirtan is known through different names all over the country. It is Hari Katha and Shiv Katha in Karnataka, Katha Kalakshepam in Tamil Nadu, Kirtan in Maharashtra, Katha in Andhra Pradesh, Katha Prasangam in Kerala, Sankirtan in Bengal, Katha Patha, Pravachan, Katha etc. in other parts of India.[i] (Ranganath, 199).

It is widely believed that Kirtan, the chanting of God’s name was the forerunner of Katha. It arose out of the Bhakti movement and is said to have originated with Sant Namdev (AD 1270-1350). Over the years Kirtan evolved into Katha. (Ranganath, p.200) The stories are typically taken from the ancient epics. The performer incorporated songs, sayings and side stories into the telling. The word Katha comes from the Sanskrit word Kath, which means to tell, narrate, relate, speak about, or explain. A Katha is in the form of a dialogue between the Kathakar and the listener. No other traditional performing art has the same level of audience involvement.

Traditional Indians are embedded in narratives. The stories they hear (or see enacted in dramas and elsewhere) and the stories they tell are worked and reworked into the stories of their own lives. Sudhir Kakkar writes: “The spell of the story has always exercised a special potency in the oral based Indian tradition and Indians have characteristically sought expression of central and collective meanings through narrative design. While the twentieth-century West has wrenched philosophy, history, and other human concerns out of integrated narrative structures to form the discourse of isolated social sciences, the preferred medium of instruction and transmission of psychological, metaphysical, and social thought in India continues to be the story”[ii]

The Katha tradition really grew during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. This coincided with the rise of the Muslim hegemony in India. Kathas did not require the elaborate superstructure of shrines and temples. They could not be targeted by iconoclasts. They “clearly circulated across, and wove together, the layered and multilingual literary culture of North India, much like songs.”(Orsini,p.328)

The rapid dissolution of the Mughal Empire led to the rise of many independent and semi-independent kingdoms. Some of these were ruled by Hindu rulers. Hindu royal patronage for Kathas and Kathakaars helped the genre to grow. The Banaras maharajas were the most influential patrons of the Manas during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Initially Tulsidas’ epic did not have a very strong appeal for the political elite. It was propagated chiefly by sadhus and middle-class people. “Beginning in the latter half of the eighteenth century, however, there was a great surge in the royal and aristocratic patronage of the Hindi epic, reflected in the collection and copying of manuscripts at courts such as Rewa, Dumrao, Tikamgarh, and especially Banaras and in the encouragement of oral expounders and the commissioning of written commentaries by the most influential among them” (Lutgendorf, p.1350).

The work of exposition and commentary came increasingly into the hands of Brahmins.

What Is A Katha?

(The scriptures are the ocean, wisdom is Mount Mandar,

and saintly people are the Gods.

Katha is the nectar distilled from their churning,

and devotion is its sweetness.)

The Katha is a slow, systematic storytelling recitation. It needs elaboration, elucidation, explanation and illustrations. Wasn’t it Tulsidas himself who claimed that Ram Katha is enigmatic, mysterious and profound and therefore needs exposition? The Katha text and its performances are a mixture of gyaan (knowledge), emotion, devotion and entertainment.

“Each tale modulates and combines registers of instruction and entertainment— through humorous/subversive situations, vivid dialogues, emotional scenes, displays of technical knowledge, and so on—so that drawing a line between “entertaining” and “enlightening/instructive” tales seems quite artificial” (Orsini,p.332)

This dual dynamic of entertainment and education/illumination/edification is central to our understanding of the Katha. It also sets the parameters for what a Kathakar must do when he begins to tell the Katha.

Kathakar

(The Kathakaar: Sri. Ramkinkar Singh Upadhyaya)

The Kathakar must be an “adhikari”, that is he must carry the weight of authority. This can come from lineage. Ramkinkar Upadhyay, for example, was the son of Pandit Shivnayak Upadhyay, who was likewise a popular vyas. Ramkinkar felt that his father’s influence on him was slight, for he recalled having been a shy child who always fell asleep when listening to pravacan and was considered to have little promise as a speaker. Yet the fact that his father was a successful performer was probably a great influence on him.

The adhikar may also emanate from the guru shishya parampara and a period of apprenticeship under a good guru used to be the norm for all Kathakaars. There is no set curriculum or training. The guru who imparts the teaching may not be a human being at all; many expounders attribute their understanding of the Manas to the grace of Hanuman. Ramkinkar Upadhyay stated that he never prepared in advance for a performance. His method, he said, was to “enter into that inner state in which Hanuman-ji, by means of my voice, may express what he wants to express. And the greater my absorption in that state, the greater the flavor [ras] in the Katha.” (Lutgendorf, 181)

Ultimately the authority must come from absolute mastery of the text. The initial phase of the internalization of the text may include a seemingly mindless repetition the language, structure, and images come to permeate the mental processes “so that there is no occurrence, word, or image encountered in life that does not immediately evoke in the devotee some parallel word, phrase, or situation from the text.” (Lutgendorf, 176)

The Kathakaar uses songs, satire, humour, gestures and interpretations to make the story contemporary and relevant. The Kathakar is both the performer and the performance. He is an ancient scholar and interpreter. He is often a gifted speaker, singer, dancer, and actor rolled into one. The Raja Manasollasa of King Someshwara III (AD1122-1133) of the Chalukya dynasty prescribes that he should be aware of sixty four ancient Indian arts, should know four languages, should be Chittajna (knower of the other’s mind), Samayajna (improviser) , Savadhana (patient) Raga Dvesh Vivarjita (devoid of emotions like hate and love), Ashtika (noble and traditional) and Vagmi (eloquent). He should be well versed in music and endowed with an attractive voice. He should have expertise in Sabhashastra (treatise in assembly manners) and scholarly in purana, shastra and geetatatwa. ( Ranganath,201) The Kathakaar would work to evoke the different rasa through his performance and create wonder and awe in the hearts of the listeners.

An analysis of the art of “Kathasamrat”, Ramkinkar Singh Upadhyaya, demonstrates the ways in which the Kathakaar reframes the story, retelling it and recreating it in his own way.

Ramkinkar Singh Upadhyaya was named after Hanuman, Ram Kinkar translating as “sevak” of Sri Ram. As a shy retiring child he had no special proclivity for public religious discourse. However a series of dreams and coincidences during his adolescence nudged him towards his destiny. At the age of twenty he decided to devote his life to exploring and explaining the works of Sant Tulsidas. He stayed for eleven months at Vrindavan. Many of the renowned saints of the region appreciated and encouraged his work, seeing in his words a reflection of the presence of God himself.

Not only devotees and saints but even intellectuals were deeply affected by the personality, wisdom and learning of Kinkarji. He was made Visiting Professor at Banaras Hindu University. His discourse, writings and teaching present a considerable body of work and demand a scholastic enquiry.

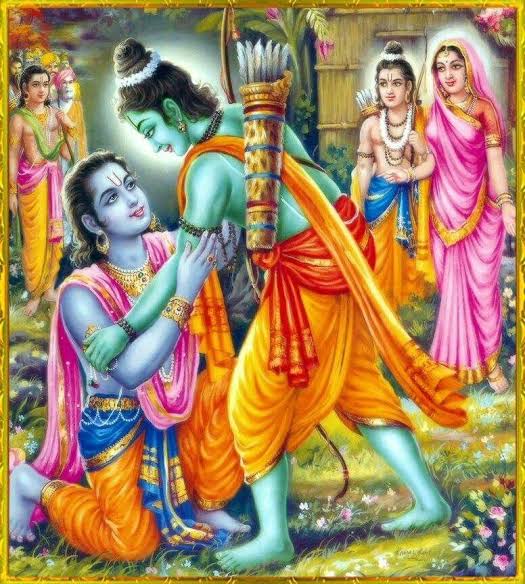

In some ways he was a one man theatre, himself both performer and performance. He was friend, philosopher and guide to his audiences. He was both scholar and interpreter. In Ram Katha Mandakani he asserts that the task of a Kathakaar is to bring the story to life in the minds of the audience across spatial and temporal distances. We see this at work when he describes and interprets the Bharat Milaap incident. Kinkar quotes from Tulsidas’ text, describes the actions and movements of the characters and then delves into their minds to reveal their inner states. Even though the words are printed on a page and are not now enlivened and animated by the rich voice and the striking personality of the Kathakaar, the reader is still moved by the exposition.

Kinkar’s success as a Kathakar was perplexing. He was the most famous and commercially successful Kathakar of his time. Yet he spoke in a flat monotone voice, used few gestures and adopted no theatrical gimmicks and few textual quotations in comparison with other Kathaakaars. It was this plainness that fuelled his popularity. He explained the Manas instead of just singing it and intellectuals flocked to his Kathas. The srotas accepted the Manas as a work of the highest inspiration and expected its grand design to be filled with hidden meanings and relationships. One of the special delights of Katha is to call listeners’ attention to meaningful structures and correspondences underlying the surface narrative. Kinkar offered reinterpretations and commentaries and related his material to contemporary times.

The crowd at one of Ramkinkar’s annual pravacan programs at

Lakshmi-Narayan Temple, New Delhi

Kinkarji distinguished between Katha and Itihas. At the simplest level Katha refers to that which is spoken. But when we look at the ways in which Ramcharitamanas mobilizes “Katha” as a genre, we will become aware of its greatness and significance. Kinkar compares the Katha to a bridge, a “setu” which links the past to the present, the distant to the near and the heart of the listener to the characters in the tale. In this way it differs from ‘ïtihas”.

For us to understand history we have to go back to the time, the place and the people that history describes. Katha brings them into our midst and into our hearts. For example the mere description of Ram Rajya in Tretayug may afford us intellectual pleasure but it does not affect our souls or our lives. That magic belongs to the genre of the Katha.

As an example Kinkar quotes the story of Sri Ram’s return to Ayodhya. In the Ramcharitamanas, Shivji is the Kathakaar and Parvatiji is the listener. Bharat, the fond brother who has been left behind and who has ruled Ayodhya on Ram’s behalf does not step forward to greet his elder brother. Why?

In their earlier reunion in Chitrakoot both brothers had met and forgotten their very selves in the love that they felt for each other. It took the sagacity of Kevat to remind Ram of where his duties lay. Kevat invoked the name of Guru Vashisht, the royal mothers, the senapati and the mantris- thus reminding Sri Ram of where his duties lay. When Sri Ram returned from exile the first person he greeted was the Guru as was the proper protocol. To ensure this Bharat stayed at a distance. Only when Sri Ram had met everyone, did Bharat rush forward and grasp his elder brother’s feet. Kinkar explains the motivation and the emotional state of Bharat at these two different meetings distanced by a span of fourteen years.

(Bharat Milap)

When they met at Chitrakoot, Bharat bowed his head in obeisance. He was ashamed of what his mother had done. He did not consider himself worthy of touching the feet of his elder brother. But now that his brother is back, Bharat grabs his feet and will not let go. He will never allow his brother to leave him again. Kinkar goes on to tell the story of an artist who painted such a life like image of God that it actually assumed a life and began to speak. “Why have you not painted my feet?”God asked.

“Because I was afraid you would walk away” the painter replied.

Bharat grips Sri Rama’s feet with the same urgency and then Sri Ram lifts him and embraces him assuring him that his love has made him prisoner and so his hands can set him free. Thus, for this episode of Bharat Milaap, Shankarji is the Kathakar and Parvatiji is the one who listens.

While both are enjoying the tale there is some emotional distance which allows Shankarji to describe the events at length. Kinkarji contrasts this with the meeting between Sri Ram and Hanuman after the burning of Lanka. There Shankarji had lapsed into silence, he was so moved by emotions.

This is the difference between itihas and Katha. Katha brings the events and the characters to us. We are no longer just describing emotions or hearing that description. We feel them too and weep when the characters are moved. When we listen to the Ramcharitmanas we should not feel that the events happened in the Treta Yug. We should feel physically and emotionally present at the birth of Sri Ram or the marriage of Ram and Sita. We should be able to relate the story to the present age and to our current difficulties. The medium of Katha is artful language, but its essence is emotional communication—which can touch inner depths or even effect a radical change of heart.

Katha is a milieu-oriented art form, arising in and inseparable from the spiritual outlook and practice of its listeners. The images and emotions awakened by such performances have as their prerequisite the audience’s intimate knowledge of sacred text. The srota too needs to be an adhikari —a term for one possessing “mastery” or “authority. Listeners do not constitute merely a random and passive audience for a rhetorical display but ideally are accomplished devotees capable of receiving in its full depth and import the fruit of the expounder’s intellectual and mystical discipline and of integrating it into their own devotional practice. In more secular artistic terms, an adhikari is also a connoisseur, and his presence is necessary to bring out the best in the performer. A great expounder desires a group of discriminating listeners who will be adhikaris of his Katha.

Ram Katha Mandakini

The title of the book draws from Tulsidas’s statement that Ram Katha is Mandakini and that the devotee’s heart is Chitrakoot itself. (Ram Kinkar, 2006, pg.13)

Kinkar based his exposition on Tulsidas’ Ramcharitamanas, quoting from the verse, offering translations and then explaining and interpreting the lines to give them contemporary relevance. Tulsidas Ramcharitamanas was never intended as a stand- alone composition. It was meant to be accompanied by prose explanations, elaborations, and homely illustrations of spiritual points because it was mysterious, enigmatic and profound. It requires exposition as only a listener who is a treasury of wisdom can grasp its inner meaning. Tulsidas himself built in the Katha format. In fact the first tellers of the tale were Luv and Kusha. Other tellers and listeners include Shiva Parvati, the crow Bhusundhi and Garuda, the sages Yajnavakya and Bharadvaj, and finally Tuslidas and his audience. The Manas is always styled and presented as a Katha and as samvad between the teller and the listener. The mileu of a Katha is also important. It is associated with satsang, the association of the good and holy.

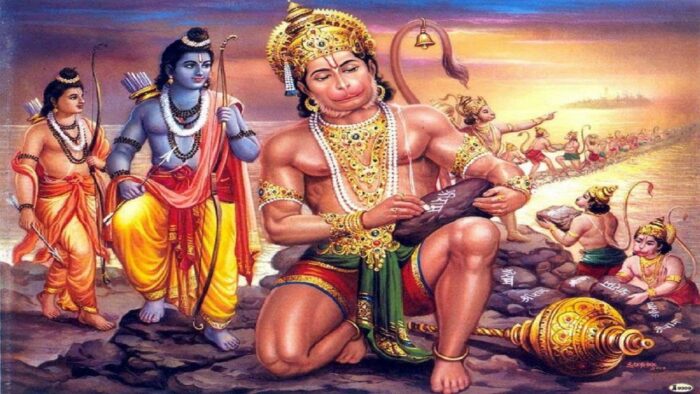

The third chapter of Kinkarji’s Ram Katha Mandakini begins with “Hari Anant Hari Katha Ananta”. (Kinkar, pg 60) God is infinite and infinite is the number of stories told around him. This applies especially to the story of Rama. The story has been spoken, chanted, sung, mimed, retold, and explained by tale-tellers, epic-singers, temple pundits and schoolteachers over generations. Kinkar distinguishes a “Katha” (story) differs from “ïtihas” in that historical accounts will all have the same facts presented in almost the same way. The Katha differs from teller to teller and across regions and time spans. In this chapter, Kinkar identifies Hanuman as the ultimate Kathakaar. He tells an infinite variety of Kathas and uses Katha as medicine as well as education. He is also the best possible listener of Kathas and it is claimed that whenever the story of Rama is told, Hanumanji sits in the audience as a listener. He tells the Katha of Sugreev to Sri Rama and the Katha of Sri Rama to Sugreev. In Lanka he told a Katha to Vibhishan. He even dared to play Kathakaar for Ravana, using the story to issue a warning of the fate that awaited Ravana. Unfortunately Ravana did not have the capacity to benefit from the Katha. When a person is filled with ego he cannot benefit from the Katha told.

Sita ma had thought of telling Hanuman to recite the Katha to Sri Rama that would remind him of his wife. But Hanuman tells her a Katha instead. It is precisely because Sri Rama is lost in love and longing for her that he has forgotten his weapons. She changes her mind and urges him to tell Sri Rama the Katha that will remind him of his “Baan”, weapon. Hanuman does not tell this tale. He tailors the Katha to the circumstances and the need of the hour. He brings tears to the eyes of Sita and Sri Rama. His Katha made Sri Ram impatient to reach Lanka and bring back his beloved wife.

When Hanuman tells the Katha to Bharat, sadness is dispelled. In fact Bharat keeps urging him to tell the story of Sri Ram again and again because each time a new rasa appears, new facts reveal themselves. Bharat and Shatrughan spend their time listening to Ram Katha again and again. Kinkarji says this is the special gift of the Kathakar. He can mould the Katha to suit the need of the listener.

The true devotee can keep listening to the Katha of Sri Ram and never tire of it. Tulsidas asked Sri Ram to live in the heart of such devotees.

Story-Text-Teller-Tellee

(Unable to recognize the Sanjeevani booti, one of the peaks of Dronagiri was carried by Lord Hanuman when Laxman was rendered unconscious by Meghnad)

Katha is a sequence of logically and chronologically related events, bound together by a recurrent focus. In Ram Katha it is Rama, the legendary warrior prince of Ayodhya, who proves the focal point as he walks the path that destiny has paved for him. The story of Ram’s journey is the story of righteousness, wisdom, good conduct which is Ram. It is a story which has transcended space and time, travelling across centuries and large swathes of land.

Every Indian knows the story of Rama. Therefore the question arises why should we listen to it again? The answer lies perhaps in the Telugu folk story of “What Happens When You Listen?”[iii]

Popular wisdom has it that if you listen to the Bala Kandam you will be blessed with progeny. If you listen to Sita Kalyanam, a long postponed marriage will materialize. Listening to Paduka Pattabhishekam will result in the granting of boons. If one listens to the story of Guha’s friendship with Rama, one gains the friendship of good people.[iv]

The Indian tradition of oral performance of the sacred texts ranges back to the Rig Veda. It is not by reading but by listening that you can truly understand. Tulsidas was perhaps the first Kathakaar of his own work. Legend goes that Hanuman himself liked to listen to Tulsidas’ Katha, being the first to arrive and the last to depart.

The Kathakar is both performer and performance. The eyes and ears of the listeners are focused on his presence. Kinkar had a deep voice and a towering personality. His audience called him YugTulsi, the Tulsidas of this yug. He was respected for his superior knowledge, wisdom and understanding and gained his authority and respect through that distinction. Writers and intellectuals also admired him. In fact in his discourse he was able to mingle Bhakti and Jnana- devotion and knowledge. His Katha was held in large assemblies of people, assumed truth telling by exposition and was highly interactive.

However, Kinkar was also criticized and attacked for his commercial success as well as his strained interpretations. Lutgendorf writes: “He is leading people astray,” one elderly vyas told me, “because he does not interpret the Manas in accordance with the Veda, which is what Tulsidas intended.” A prominent mahant of Banaras concurred, “His interpretations are fabricated out of his own mind; Goswami-ji never even imagined such things!” In an interview, Ramkinkar countered such criticism by observing wryly that anyone who said anything new could expect to be similarly reviled. Hadn’t the Brahmans of Banaras assailed Tulsidas himself for his supposed “innovations”?

And others will come after me, and they too will ponder in their hearts, they too will develop their ideas from the perspective of a welling up of feeling; and those same dogmatic people will oppose them too. Only then they will use my ideas in their arguments, saying “What he said, that is ancient and traditional.” (Lutgendorf, p.230-231)

What set Ramkinkar apart, aside from his singular commercial success, was his tendency to move away from a literal interpretation of the story in order to make it more relevant to the concerns of his audience. The tremendous response that his effort elicited—reflected in the designation “emperor of Katha” (Kathasamrat) suggests that as academicians and as storytellers we may need to resurrect this indigenous form of storytelling in order to connect more deeply and meaningfully with the people of our country.

[i] Ranganath,H.K. “Katha-Kirtan” in India International Centre Quarterly Vol. 10, No. 2, MEDIA: response and change (JUNE 1983), pp. 199-205

[ii] Kakar,Sudhir. Intimate Relations. Exploring Indian Sexuality. New Delhi:Penguin Books, 1991 p.8

[iii] Retold by Ramanujan, A.K. in Richman, Paula ed. Many Ramayanas : The Diversity of a Narrative Tradition in South Asia.California:University of California Press, 1991. p. 46-48

[iv] https://www.thehindu.com/features/friday-review/religion/Listening-to-Ramayana/article15691428.ece

REFERENCES

Lutgendorf, Philip. The Life of a Text. Performing the Ramcaritmanas of Tulsidas. Berkeley: University of Ccalifornia Press, 1991

Ranganath, H. K. “Katha-Kirtan.” India International Centre Quarterly, vol. 10, no. 2, India International Centre, 1983, pp. 199–205, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23001644.

Richman, Paula. (ed) Many Ramayanas: The Diversity of a Narrative Tradition in South Asia.California:University of California Press, 1991

Upadhyaya, Ram Singh Kinkar, Ram Katha Mandakini. Ayodhya: Ramayanam Trust, 2006.

Feature Image Credit: Ram Dass

IndigenousStorytellingTraditions

Watch video presentation of the above paper here:

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.