1. Introduction

1.1: How I started my inquiry into the creative process?

As an Indian classical dancer, I often pondered at the choreographic process of the doyen/doyenne masters in my field. Delving deep into the mind of the choreographer, I could gain insights that the final product, be it an ensemble production or a one-off piece was, not just the time taken to arrive at that piece of work but time spent hours or probably years before reaching the point of choreography. The creative process can be sometimes spontaneous while at other times more methodical.

1.2: Inter-relationship between art forms

An important feature of Indian art is that there is a thread of continuity, not only in a chronological sense but from one art form to another.

The following dialogue between a rsi and a king brings out the interconnection between the various art forms rather vividly:

King: O Sinless One! Be good enough to teach me the methods of image making.

Sage: One who does not know the laws of painting can never understand the laws of image-making.

King: Be then good enough, O Sage, to teach me the laws of painting.

Sage: But it is difficult to understand the laws of painting without any knowledge of the technique of dancing.

King: Kindly instruct me then in the art of dancing.

Sage: This is difficult to understand without a thorough knowledge of the laws of instrumental music.

King: Pray teach me the laws of instrumental music.

Sage: But the laws of instrumental music cannot be learned without a deep knowledge of the art of vocal music.

King: If vocal music be the source of all arts, reveal then to me, O Sage, the laws of vocal music. (Mulk Raj Anand, Hindu View of Art, 1957)

Any discussion on the inter-relationship of the Indian arts at the level of theory or praxis is meaningful only if we realise that all the Indian arts are as if the myriad petals of a single flower. Each petal is clearly definable, has autonomy in shape and form, but has life and vitality only as part of a ‘whole’. (Kapila Vatsyayan, Inter relationship of the arts)

1.3: Modern meditative practices & contemplative art practices

Off the many modern meditative practices, guided meditation and contemplative art practices propel creativity by using a mix of ancient & modern techniques. For instance, guided meditation relies on the process of scripting, focus on breath control, and visualization to achieve desired outcomes of sleep, relief from PTSD & even improved creativity.

While techniques in contemplative art practices may include for instance an activity like, ‘gazing at a painting, not glancing it’ and answering the following questions;

- What did you first notice about this image?

- What else did you notice as you kept looking at it?

- What thoughts went through your mind while you were looking at this image?

- What feelings or memories (if any) did it bring up for you?

In the same vein, exploring the process underling Indian sculpture and poetry while focus on contemplation or ‘dhyana’ is what is explored in this paper.

2. Dhyana in the context of sculpture

2.1: An Introduction

Man, as Tagore says, is indeed a “maker of forms”, for he is most content to contemplate beauty, but is impelled to give his vision a visible form.

The Vastusutra Upanishad, says “on account of having two aspects (nirguna and saguna) Brahman acquires form.

In the book titled, ‘Adavita of art’ by Harsha V. Dehejia Chapter 2 ‘Saksatartha: Rupabrahman’ he distinguishes between the dhyana of the sage artist and the dhyana of those who follow after him.

He goes on to say, although there are no references in the texts to historical personages who were sage artists, it is evident that dhyana, or artistic contemplation that gives birth to an original aesthetic form must differ from the psychological process through which others reinterpret this model.

Second and subsequent generations of artists, who recreate the same or similar type of rupas, are acting under historical & psychological conditions that differ from the sage artist.

The aesthete is to take his cue from the sage artist, the sage artist ādi silpi, rather than from the subsequent generations of artists.

2.1: Steps in the creation of a form

- The first step in the evolution of the rūpa is the dhyana of the artist. In this first step, the conception of rupa is dependent on the coming together of the artist’s individual genius, inspiration (pratibā) & his discipline for contemplation (dhyana) which has its focus on the traditional imagery of the cosmic Purusa. It is this step that transforms rūpa from formless to form, “arūpad rūpam”.

- Dhyana for the Indian artist was a disciplined activity & one that could be deliberately induced.

- The dhyana of the artist is not a trance, in the sense of a loss of volitional control or a contentless ecstasy, but a meditative discipline focused on the cosmic Purusa, with the express purpose of revealing its form.

- The artist sees the form of the cosmic Purusa, in his dhyana just as the Vedic rsis hear the cosmic sounds out of which they compose hymns.

- The actual making of an image by the Hindu artist would involve some such process as this, the artist performs purificatory ablutions & sits down to focus his attention on such a dhyana mantra. He then offers flowers, incense and gifts to the form conceived. The mental picture is thus seen in all its details & the work of art is complete in the mind before being translated into form. The artist then begins the task of technical elaboration, during which he must hold fast to the conception evolved through yoga, contemplation, and strain every nerve to translate it perfectly into form.

2.2: Intention of the artist

- The desire on the part of the sage artist to visualise the cosmic Purusa is the key to the entire dhyana.

- As the Vastusastra Upanishad says, “The intention to worship leads to the appearance of a particular form” (Sankalpad vikalpa iti visesah).

- The sage-artist adores and delights in the form that rises in his mind.

- As the VSU says, “it is the process of dhyana that the form becomes clear”. dhyānaprayoge rūpa sausthavam spastam bhavati (Dehejia, Advaita of Art)

2.3: Deliberate invocation of dreams

The kind of mental state designed to be secured through the practice of yoga can also be cultivated by the artisan through tuning up the functions of the body and the mind into perfect obedience to the faculty of intuition and through the deliberate invocation of dreams.

The relaxation of the body and mind helps to evoke the intuitive faculty, “while dwelling on the knowledge that presents itself in dreams or sleep”.

It is recommended by Patanjali, the author of the yoga system, as a means of realizing the vision desired.

And as we have seen in the Agni Purana, the imager is advised on the night previous to starting work to perform purificatory ablutions, and on going to bed to pray:

“O thou Lord of all gods, teach me in a dream how to carry out all the work I have in mind”. (Mulk Raj Anand, Hindu View of Art, 1957)

2.4: Contrasting ordinary modes of recalling images with the dhyana of the artist

Heinrich Zimmer contrasts our ordinary modes of recalling images that have arisen in our consciousness with the dhyana of the artist. He points out that “our untrained inward sight is generally successful in recalling images that have appeared only to vanish immediately”. By contrast, in the supra-sensory inner vision of the artists’ dhyana, these images remain stable and ensure that they are translated into aesthetic form.

3. Dhyana in the Context of poetry

The general nature of the method used by practicing artists was the same both in literature and art.

In the same vein, as we have discussed above, we see the role of intention, darsana and artistic contemplation by adi kavi, Sage Valmiki to give us the Ramayana.

3.1: Intention of the Poet

Saint Narada visits the hermitage of Valmiki. The follow account is taken from Chapter 1 of Balakanda. (Valmiki Ramayana)

तपस्स्वाध्यायनिरतं तपस्वी वाग्विदां वरम् ।

नारदं परिपप्रच्छ वाल्मीकिर्मुनिपुङ्गवम् ।।1.1.1।।

Ascetic Valmiki enquired of Narada, preeminent among the sages ever engaged in the practice of religious austerities or study of the Vedas and best among the eloquent.

कोन्वस्मिन्साम्प्रतं लोके गुणवान्कश्च वीर्यवान् ।

धर्मज्ञश्च कृतज्ञश्च सत्यवाक्यो दृढव्रत:।।1.1.2।।

“Who in this world lives today endowed with excellent qualities, prowess, righteousness, gratitude, truthfulness and firmness in his vows?

चारित्रेण च को युक्तस्सर्वभूतेषु को हित: ।

विद्वान्क: कस्समर्थश्च कश्चैकप्रियदर्शन: ।।1.1.3।।

Who is that one gifted with good conduct, given to the wellbeing of all living creatures, learned in the lore (knowledge of all things that is known), capable of doing things which others cannot do and singularly handsome?

एतदिच्छाम्यहं श्रोतुं परं कौतूहलं हि मे ।

महर्षे त्वं समर्थोऽसि ज्ञातुमेवंविधं नरम् ।।1.1.5।।

O Maharshi, I intend to hear about such a man whom you are able to place? Indeed great is my curiosity”.

Following which Saint Narada, gives us an account of story of Rama as ‘Samkshepa Ramayanam’’ which is Chapter 1 of Balakanda.

3.2: Inspiration – evoking rasa – sight of the kraunca birds

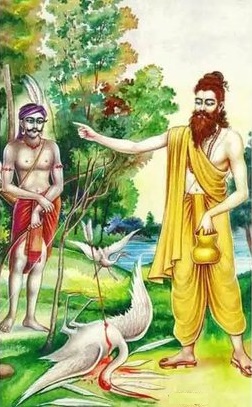

(Figure 1: Credit: Pinterest.com – Sage Valmiki cursing the hunter for killing the male Krauncha bird with an arrow)

Valmiki goes to river Tamasa for morning ablutions’. He sees a male krauncha being shot down by a hunter — expresses the reflection of a female companion’s sorrow in his experience in the form of a sloka in metrical form.

मा निषाद प्रतिष्ठां त्वमगमश्शाश्वतीस्समा: ।

यत्क्रौञ्चमिथुनादेकमवधी: काममोहितम् ।।1.2.15।।

“O fowler, since you have killed one of the pair of infatuated kraunchas you will be permanently deprived of your position”.

Valmiki who had witnessed all that had happened was filled with compassion. He involuntarily burst into a poetic verse that seemed to flow out, spontaneously without any effort on his part. “O Fowler! Thou hast so cruelly killed the male of a pair of Krauncha birds while they reveled. On that account you will be discredited forever. Just as you ended the bird’s life before its time, so too shall wilt your life before its time”. Having uttered his versified curse, Valmiki became thoughtful, “What has come over me? Why did I curse a fellow being? Was it my sorrow at the helpless wailing of a bird or does it have a hidden meaning? Born out of the pathos of a slain bird, some words have escaped me without my conscious effort. They are so arranged as to follow a metre and are viable for rendition in the form of a song, to the accompaniment of string instruments, hence let it be known as a ‘sloka’.

3.3: Power of clairvoyance by Lord Brahma

Lord Brahma appears at the hermitage — directs him to compose the great poem in the same metre describing the story of Rama as related by Narada — grants him the power of clairvoyance.

रहस्यं च प्रकाशं च यद्वृत्तं तस्य धीमत: ।

रामस्य सहसौमित्रेः राक्षसानां च सर्वश: ।।1.2.33।।

वैदेह्याश्चैव यद्वृत्तं प्रकाशं यदि वा रह: ।

तच्चाप्यविदितं सर्वं विदितं ते भविष्यति ।।1.2.34।।

The incidents pertaining to sagacious Rama together with Lakshmana, Sita, Bharata, etc. and the rakshasas their deeds, thoughts, unknown or known to everybody and even not known to you, will be revealed to you by my grace.

3.4. Meditation in the context of artistic contemplation & visualisation

The poet is but an instrument who by the Grace of the Divine, after polishing his faculties, is granted the poetic eye or perception, contemplating on the darsana & then goes on to compose his work of art.

श्रुत्वा वस्तु समग्रं तद्धर्मात्मा धर्मसंहितम् ।

व्यक्तमन्वेषते भूयो यद्वृत्तं तस्य धीमत: ।।1.3.1।।

Hearing the entire story of Rama from the intellectual Narada, the righteous (Valmiki) sought to know clearly more about the history of Rama endowed with wisdom.

उपस्पृश्योदकं सम्यग्मुनिस्स्थित्वा कृताञ्जलि: ।

प्राचीनाग्रेषु दर्भेषु धर्मेणान्वेषते गतिम् ।।1.3.2।।

Having performed achamana, Valmiki seated on kusha grass with folded palms, searched for the course of past events in the history of Rama by his power of penance.

रामलक्ष्मणसीताभी राज्ञा दशरथेन च ।

सभार्येण सराष्ट्रेण यत्प्राप्तं तत्र तत्त्वत: ।।1.3.3।।

हसितं भाषितं चैव गतिर्या यच्च चेष्टितम् ।

तत्सर्वं धर्मवीर्येण यथावत्सम्प्रपश्यति ।।1.3.4।।

By the power of his penance, the holy sage visualised clearly Rama, Lakshmana and Sita, king Dasaratha, his wives and his kingdom and all that they had observed,

experienced, endeavoured during the course of events. He also visualised clearly their laughter and conversation exactly as in real life.

तत: पश्यति धर्मात्मा तत्सर्वं योगमास्थित: ।

पुरा यत्तत्र निर्वृत्तं पाणावामलकं यथा ।।1.3.6।।

With the power of yoga, the righteous (Valmiki) saw clearly, like an amalaka fruit in the palm of the hand the entire course of events that happened in the past relating to Rama.

References

Dehejia, H. V. (Advaita of Art). Motilal Banarasidass Publishers, Delhi.

Kapila Vatsyayan, I. w. (Inter relationship of the arts). IGNCA website. Retrieved from https://ignca.gov.in/inter-relationship-of-the-arts-kapila-vatsyayan/)

(Hindu View of Art, 1957). In M. R. Mulk Raj Anand, Original from Visnudarmottaram (p. 61). Asia Publishing House.

(Valmiki Ramayana). Retrieved from https://www.valmiki.iitk.ac.in/

Feature Image Credits: dremstime.com

HinduMeditationTraditions&Techniques

Watch video presentation of the above paper here:

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.