Abstract

Picking an instance of theft from Kālidāsa’s Abhijñānaśākuntalam and studying it for analysis is the objective of this article. Here, an attempt is made to observe and understand the nuances of interrogative strategies, then & now. The scope includes understanding the strategies or meta-strategy of those times; whether they seem similar or dissimilar to the practices of later times. Broadly, the attempt is at portraying a comparative picture of investigative methods of both times.

Introduction

Aristotle, the Greek philosopher, says “It is in justice that the ordering of society is centered ”. Everyone wishes to live in an ordered, peaceful and harmonious society. To ensure that such a society flourishes, laws, rules and justice become necessary. Humans comprise noble as well as evil attributes. Given an opportunity, these demonic traits can swiftly assume gigantic proportions and topple the existing moral framework. In order to avoid such drifts, it is essential to recognise the demon living inside and understand the way it works. This task of watching out for evil tendencies had been done right from the ancient times.

Our scriptures always warn us of evil tendencies and how they can gradually spiral into notorious behavior patterns. Such tendencies can also catch us totally unawares. We might end up getting caught in emotional tornadoes and lose our senses. To stay clear of these follies and pitfalls, Sṁrti texts prescribe dharmic ways of life. They also instruct on how wrongs, crimes or offences have to be detected, monitored and punished. Only this will ensure that Mātsyanyāya does not prevail as mentioned by Kautilya in his Arthaśāstra.[1] Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇa also tells us that only punishments are suitable for the ungrateful. Kṣamā (forbearance) sāma (conciliation) and dāna (charity) are only wasted on the ungrateful lot. [2] It should be noted that when punishments are awarded they have to be according to the gravity of the offence. As Kautilya notes, one who prescribes mild punishments is abhorred and one giving harsh punishments is considered a terror. One who delivers suitable punishments alone is revered.[3]

Dharmaśāstra texts in the vyavahāra section, delineate law into eighteen different titles[4]. All the legal disputes and matters will fall under one or more of the sections mentioned in the list. Theft (steya), the topic of this study is the twelfth amongst the eighteen.

In the Indian penal code, Article 378[5] defines theft. Whoever, intending to dishonestly take any moveable property out of the possession of any person without that person’s consent, moves that property in order to such taking, is said to commit theft. It mentions that the taking could be temporary or permanent, it may or may not have been beneficial for the accused. Section 379 awards imprisonment up to three years and or fine for this offence.

With this brief introduction into the crime of theft, let us look at the theft segment in Abhijñānaśākuntalam. This study strives to focus on the investigation procedure following the arrest of the suspect. It observes the way things unfold thereon. Further, it attempts to depict the past event, that mirrors the society, with the present day scenario.

Literature review

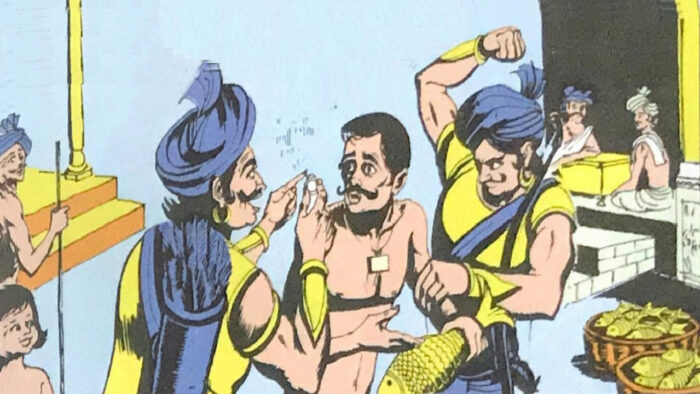

The sixth act of Abhijñānaśākuntalam, presents the theft interrogation scene to us. The Police chief (Śyāla) and his constables (Sūcaka & Jānuka) interrogate the fisherman (Dhīvara) who is caught red-handed with the king’s ring that is lost by Śakuntalā.

The constables beat up Dhīvara, brand him as a thief and pose a direct question about the manner in which he had acquired the ring. The Dhīvara submits with fear that he had not committed any crime. Then Jānuka remarks sarcastically if it was a gift by the king for a worthy brāhmaṇa. Dhīvara calmly discloses his identity as a fisherman and place of residence as Śakrāvatāra. At this, Jānuka abuses him that his caste was not in question.

At this point, the Śyāla intervenes, asks Dhīvara to narrate the events in sequential order to understand the situation clearly. He also asks Sūcaka not to interrupt the narration. Now, Dhīvara says about his profession with which he supports his family. Here, too, there is an irrelevant caustic remark. There is an apt reply by the Dhīvara regarding nobility of a profession and how it should not be forsaken. This mistake of irrelevant remark is rectified quickly by the Śyāla. He asks Dhīvara to proceed with the narration. Then the Dhīvara speaks more. He tells that he caught a Rohita fish one day and in its maw, he found the ring. When he went ahead to sell it, he was caught. He says this and leaves it to Śyāla to believe it or not. The police also note the strong smell of flesh on the Dhīvara’s person. By his narration and by the inference from the odor, his professional identity is established.

Śyāla says that to find the truth about the possession of the ring, he has to be taken to the rājakula (justice hall of the king). In the rājakula, Śyāla goes to meet the king to ascertain the truth about the ring. He entrusts Dhīvara with Sūcaka & Jānuka. These two constables are still not convinced of the identity of the Dhīvara. It takes a while for Śyāla to return. In the meantime, the policemen continue to abuse him as a thief. Sūcaka hints at the possibility of execution as a punishment for Dhīvara. He comments that he is waiting to garland (for execution) Dhīvara. When they see Śyāla arriving with a document in hand, they assume it is the royal mandate to punish Dhīvara. They tell him that probably he could be impaled and thrown away as gr̥dhrabali (getting killed; dead body left to be eaten away by vultures) or śunomukha (getting buried shoulder-deep; allowing dogs to tear away). However, Śyāla conveys that Dhīvara can be released. Sūcaka remarks that he had indeed returned from the abode of death. Dhīvara is extremely delighted and bows to Śyāla and asks him about his profession. This reminds Śyāla of the gift offered by the king to Dhīvara. He gives the money to Dhīvara which is equal to the value of the ring. Sūcaka is still in a state of wonder and comments that the Dhīvara is taken down from the gallows and lifted up on elephant back. The fisherman happily wishes to share half the money with the Police chief. This makes the policemen really happy and the chief considers the fisherman a friend now. They proceed together to celebrate their friendship with a drink of wine.

III. Synthesis & Analysis

Context

In the initial portion of the fifth act the poet hints at Duṣyanta forgetting Śakuntala through the song of Hamsapadikā[6]. As Duṣyanta listens to the song, he wonders why it is creating a feeling of longing in his heart, though he is not separated from anyone dear to him. Again, towards the end of the act when Śakuntala finally disappears miraculously, he gets a feeling that she may be saying the truth, but that he is unable to recollect anything of that sort[7]. His mind is really stirred and set for introspection.

Moreover, this act is quite heavy with emotions. The minds of the audience are also perturbed seeing the innocent Śakuntala go through a lot of turbulence. Then, comes the sixth act where the fisherman is caught by the policemen. This episode is mundane and gives a peek into the life of commoners – What happens in the life of the fisherman who is caught in self-incriminating conditions, how he goes through it, whether the system is robust enough to look at his innocence. This provides a complete relief from the heaviness of the previous act. This also leads to the climax. Only due to this episode, Duṣyanta finally sees the ring and remembers Śakuntala.

Incident proper

The sixth act begins, with the stage direction telling us that the two policemen enter with the suspect whose hands are bound behind his back[8] . This practice of hand-cuffing is seen in the present times also. In Mālavikāgnimitram, there is reference of fettering the feet of the offenders as well.[9]

The investigation itself starts with the policemen hitting the fisherman before getting any of his details. Practice of tormenting suspects to evoke confession was existent during the times of Kālidāsa. There are references to such treatment of suspects in the Arthaśāstra, though not as freely as is found in this segment. Kautilya gives instructions as to the manner of interrogation in an investigative procedure. He says that in the presence of the victim and witnesses, the suspect has to be questioned about his identity and place; his recent activities and movements till the time of arrest. These statements have to be corroborated with the statements of others. If statement of suspect turns out to be in unison with that of others, he/she is not guilty, else is put to torture to extract truth.[10]

It is to be remembered that torture is the last resort after collecting enough background information and preliminary details from the suspect. However, in this theft episode, the police treat the suspect with impatience. They hit him despite any evidence to prove his theft. This sort of third degree treatment only breaks down the dignity of the suspect and makes him hostile. As against this, present day law books do not prescribe third degree treatment at any stage of investigation. Though hitting and abusing the accused is quite commonly prevalent, it is not instructed in the law books. The reason is quite obvious. Out of fear of torture, the accused may confess to something he never did. Hence, the statement of the suspect in police custody is not considered valid in the courts. Whatever he utters in the presence of the magistrate alone is taken into account.

In the case of the fisherman, without asking about any background information, the police ask him about the ring, head-on. They have resorted to direct questioning which does not yield any result in an investigation.

Crime investigation is actually a combination of application of various sciences. It is about dealing with people involved in the crime scene coupled with the ability of the investigating officials. When the officials do not possess the requisite competence, they fail to pay attention to finer nuances of the situation in hand, of the people involved and fall short of grasping the big picture of the crime.

According to the Police Act 1861, crime prevention and crime detection are the foremost duties of the police. This demands utmost professionalism in their conduct and character to discharge their duties keeping the law of the land as the pivot. This necessitates a robust training programme to instill the essential qualities of a good investigating officer which include good knowledge of the law of the land, clarity of the legal procedures, understanding the validity of evidence available as well as handling the suspect with an understanding of human psyche. When training focuses on such values, the moral compass of the entire police force will be pointing in the right direction. Such building of culture in the institution will help in cohesive bonds to tackle menaces with a lot of strength.

In the theft episode, a policeman makes unnecessary and quite contemptible comments about the caste of the fisherman. Though the fisherman retorts with poise, the policeman only gets more perturbed. He flares up saying there is no question about the caste. It is evident that such unprofessional remarks derail the process of interrogation. It just points out the lack of essential professionalism.

Section 313 of the Code of Criminal Procedure 1973, tells us that the accused has to be heard in the interest of justice and fair play, not just as a formality. The accused gets the right to explain his position in the background of incriminating evidence against him.

Nonetheless, the chief of Police brings the investigation back on track, by asking the fisherman to narrate the whole episode in proper sequence. This is a sensible intervention to understand the nature of the suspect and the validity of his story. The chief additionally asks the policemen not to interrupt the fisherman as he describes the events. This gives the fisherman enough confidence to narrate the story as there is someone to listen. This intervention is noteworthy as the chief understands the shortcomings of his subordinate officials and the need to allow the suspect to present his views.

There is another point that captures our attention. When the subordinate policemen are ordered to allow the fisherman to speak without interruption, they respond to the chief saying ‘yadāvutta ājñāpayati’ (as the brother-in-law commands). Though the policemen have to obey the chief’s order, they address him as āvutta. This could probably be to console themselves that they are only listening to their āvutta and not their master. It may also be considered that they obey their officer wholeheartedly as they would do a family member.

In one instance, the chief, too, commits a folly. He is quick in correcting himself, though. When there is a statement about the fisherman’s livelihood, he makes an irrelevant comment about the nobility of the profession. After getting a reply from the fisherman about being steadfast in one’s own profession[11], the chief asks him to continue with his narration. Now, the manner in which the fisherman got the ring is told. At this stage, the identity of the fisherman is established by his narration and the corroboration with the smell of raw flesh on his person.[12] But, the manner of obtaining the ring is yet to be ascertained. So, they decide to take him to the rājakula.

In the meanwhile, the police continue to abuse him verbally too. They call him granthi-bhedaka (cut-purse, one who breaks a knot to steal). Earlier, they called him kumbhīraka (robber). Interestingly, we can find reference to punishments for those who abuse a non-thief as ‘thief’. Kautilya mentions this aspect in his Arthaśāstra. If the innocence of the suspect is proven, then the abuser deserves punishment that is given to a thief. It also adds that one who hides a thief too gets the same punishment. [13]

Further, when they go to the rājakula, the chief alone goes inside to meet the king. He waits for the king’s availability. This shows that the chief had the authority to directly report to the king. The king, upon seeing the ring, is reminded of his past life and immediately issues the sentence to release the fisherman[14]. He also awards a prize money equivalent to the value of the ring.

A little while ago, when the fisherman was left with the other two policemen, they hint at possible punishments that await the suspect in this case. There is reference of getting the convict killed by animals like gr̥dhrabali and śunomukha. Manu refers to this śunomukha as the punishment to a woman who abandons her husband and goes to another man[15]. Kautilya talks about getting torn by bullocks. When a woman kills her husband or some elder or her children or sets fire to a house or gives poison or breaks into a house, she is sentenced to be torn away by bullocks.[16] Yajñavalkya says that those who steal horses and elephants, those who help prisoners flee and the cold-blooded murderers have to be impaled on a śūla.[17] In other Sṁṛti texts too, we find references of punishments for theft. In the Manusṁṛti there is the mention of impaling the convict on a sharp stake. [18]Manu also says that for stealing precious gems, capital punishment is to be given.[19] Nārada too, concurs with Manu’s views and instructs that capital punishment be awarded to the one who steal precious gems. Yajñavalkya also opines that the criminals have to be killed in different ways. [20] However, reference for gr̥dhrabali could not be found.

When we pay attention to the attitude towards abuse suspects, it is seen that it was quite existent then and continues to be prevalent nowadays. In the theft episode of Abhijñānaśākuntalam, though the suspect tries his best to maintain his composure, he gets provoked in several ways. A policeman even says that his hands throb to garland the fisherman with vadhasumanas (garland of flowers to be put before getting killed).[21] The fisherman maintains his composure by stating that without reason, murder is not to be contemplated.[22]

For the innocent, who are caught, due to completely unfavorable circumstances, this Śākuntalam incident is an assuring reminder to remain composed in troubled times, as justice takes its own time, before getting delivered.

Finally, the police chief brings the good news of the suspect’s release, to the surprise of the policemen. The fisherman is delighted at the news and at the token of appreciation from the king. He willingly offers half of the money to the police chief who reciprocates with friendship.

Such an offer of half the prize money by the fisherman need not be viewed as bribery as the fisherman had already obtained his release. It is probably to placate the officials as now he is in a happy mood, being released from the clutches of law. The police could have refused the offer if they were steadfast in their principles. But, the policemen have not. They seem to be happy. It is possible that they expected some good reward from the king as the ring belonged to someone dear to the king (This is brought out through the observation of the police chief, who notes that, the usually composed king was agitated for a moment as he had a look at the ring[23]). Or it could be just a plain token of friendship that blossoms between the suspect and police officials. This phenomenon of friendship is not uncommon, given the strange situations in which they meet each other!

Modern law viewpoints

The case taken up for study tells us about the fisherman getting the possession of a royal ring by chance. This is more about misappropriation than theft. The fisherman did not steal it. He acquired it. In the case of theft, intention is dishonesty. But in the case of criminal misappropriation, the person has no negative intention. The possession might be due to innocence or indifference. Subsequent to possession, as it is not one’s own, the person should find ways of locating the owner or hand it over to police. He cannot possess something that belongs to others as his/her own. This is what happened to the fisherman. He just went ahead to sell the ring though it was not his own.

Section 403 of IPC defines misappropriation of property – Whoever dishonestly misappropriates or converts to his own use any movable property, shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to two years with or without fine. Further explanations of this particular section says that a case where:

“A” finds a valuable ring, not knowing to whom it belongs. “A” sells it immediately without attempting to discover the owner. He is guilty of the offence under this section.

This makes it clear that our fisherman is guilty under this section. The only difference is that he was caught when he attempted to sell it.

Conclusion

It is quite evident that an investigation primarily aims to identify the perpetrator of a crime, spot him and dig out the truth from him, gather enough evidence to carry on the prosecution so that the legal forum pronounces the deserving judgement on time. All these steps in the process of investigation are inevitably inter-linked. Hence, the officials have to secure the whole process and cement any gaps in it.

The case of theft taken up for analysis in this article is a case of minor crime with respect to the nature of offence but with respect to the stolen article, being the king’s ring, it assumes a lot of importance. The policemen do not take any chances in letting the suspect loose. More so, as he was caught red-handed.

As we have seen in the earlier section, authoritative law books of ancient India prescribed even death penalty for theft related crimes. They also speak of resorting to torture when all methods fail. Hence, in the case of the fisherman, the police seem to freely resort to hitting him and abusing him verbally.

It is quite interesting to note that though Arthaśāstra prescribes torture to evoke confession from the offender, it also lays down that a non-thief should not be abused as a thief and lays down punishment for the abuser. This makes it clear that unless there is enough ground for suspecting the accused, he should not be subjected to abuse or any form of third degree treatment.

When the situation of the present day is looked at, we see that the police have multiple responsibilities and fresh challenges that technology throws at them. Police officers have to identify criminals who may be in remote locations, using technology to steal. With concepts like the internet of things (technology where devices could communicate with each other with minimal human intervention) and Artificial intelligence (technology that helps machines to mimic human actions like learning and decision-making) the challenges are compounded. This again points to integrating ethical values, professional and technological expertise to detect or prevent crimes.

One-size-fits-all is never going to work in policing. Depending on the nature of offence, the psychology of the criminals and the people who are likely to be victimised, innovative strategies and methodologies have to be devised and implemented. Constant training of police officers, not just about the theoretical aspects, but mentoring of junior officers by senior officers in solving ongoing cases will brighten chances of strong upskilling. Peep into the past literary sources to take inputs on staying morally upright, understanding the psyche of different sections of people is a sure way to improve. Academic talent pools may be created to revise training strategies. The talent pools will work towards obtaining knowledge as a heterogeneous mixture of ancient ideas coupled with modern practices currently employed in various fields/nations.

In this direction, a recent newspaper article deserves mention. The Digital University of Kerala, working towards smart governance methods is conducting training programmes for the police in the field of applications of Artificial Intelligence called Technology-aided-policing. Projects like:

- Investigation assistant chatbot: answers queries of investigating officers,

- Antisocial behavior in social media: on the basis of deep learning analysis of social media posts, predicts and verifies fake or abusive content,

- Prediction of crime hotspots: analyses existing data for deployment of police personnel,

- Prediction of culprits based on modus operandi: maps various crimes and narrows down criminals,

- Face attribute manipulation: lists out possible manipulations that can be used by a criminal to evade police networks,

are being taken up now. Such measures when implemented can go a long way in improving policing styles and in protecting the public. To conclude, the quotes of Jeremy Bentham, and Ovid are apt as they tell us the ultimate goal of policing and judiciary.

“We now come to the principal object of law – the care of security. That inestimable good, the distinctive index of civilisation, is entirely the work of law. Without law, there is no security, and, consequently, no abundance, and not even a certainty of subsistence; and the only equality which can exist in such a state of things is an equality of misery”

– Jeremy Bentham (English philosopher, jurist and social reformer)

“Laws are made to prevent the strong from always having their way”

– Ovid (Roman poet, Publius Ovidius Naso, popularly called Ovid)

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to Justice Prabha Sridevan (Retired), High Court, Chennai and Mr. Sreenath Namboodiri (Assistant Professor of Law, Christ (deemed to be university), Delhi NCR campus) for their comments and recommendations.

Select Bibliography

- Kale, M.R. The Abhijñānaśākuntalam of Kālidāsa. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Private Ltd.

- Ram Prasad, Das Gupta (2007). Crime & Punishment in Ancient India. New Delhi: Bharatiya Kala Prakashan.

- Biswas, U. N. (1987). Crime & Detective Sciences in Selected

Ancient Indian Literature.Calcutta: Royal Asiatic Society.

- Meena, Shukla (2000). Smrithi Granthon mein varnita samaj – Manu smriti, Yajnavalkya smriti & Parashara smriti (tulanatmak adhyayan). Eastern Book Linkers.

- Bist, B. S (2004). Yajnavalkya Smriti. New Delhi: Chaukhamba Sanskrit Prakashan.

- Sirca, D. C (1974). Studies in the Political & Administrative Systems in Ancient & Medieval India. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Private Ltd.

- Altekar, A. S (2009). State & Government in Ancient India. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Private Ltd.

- Julius, Jolly (1889).The Minor Law Books. Sacred Books of the East series.https://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/sbe33/index.htm

- Krishnamurthy, S (2015). Questioning an accused. Hyderabad:S.V.P National Police Academy.

- Indian Penal Code. Gurgaon, Haryana: Lexis Nexis.

- Baker, Dennis.J (2017). Glanville Williams -Textbook of Criminal Law. London: Sweet & Maxwell.

- Narang, Satya Pal (1996). Juridical Studies in Kalidasa. New Delhi: Rashtriya Sanskrit Sansthan.

[1] अप्रणीतस्तु मात्स्यन्यायमुद्भावयति। बलीयानबलं हि ग्रसते दण्डधराभावे ॥ (Arthaśāstra.I.4.13-14)

[2] दण्डो एव वरो लोके पुरुषस्येति मे मतिः ।धिक् क्षमामकृतज्ञेषु सान्त्वं दानमथापि वा ॥ (Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇa.VI.22.48,49)

[3] तीक्ष्णदण्डो हि भूतानामुद्वेजनीयो भवति । मृदुदण्डः परिभूयते । यथार्हदण्डः पूज्यते । (Arthaśāstra.I.4.8-10)

[4] तेषामाद्यमृणादानं निक्षेपोऽस्वामिविक्रयः ।संभूय च समुथ्थानं दत्तस्यानपकर्म च॥

वेतस्यैव वादानं संविदश्च व्यतिक्रमः। क्रयविरयामुशयो विवादः स्वामिपालयोः ॥

सीमा विवादधर्मश्च पारुष्ये दंडवाचिके । स्तेयं च साहसं चैव स्त्रीसंग्रहणमेव च ॥

स्त्रीपुंधर्मो विभागश्च द्यूतमाह्वय एव च । पदान्यष्टादशैतानि व्यवहारस्थिताविह ॥(Manusṁrti.VIII.4-7)

[5] All articles relating to IPC mentioned are available at https://legislative.gov.in/sites/default/files/A1860-45.pdf

[6] अभिनवमधुलोलुपस्त्वं तथा परिचुम्ब्य चूतमञ्जरिम् ।कमलवसतिमात्रनिर्वृतो मधुकर विस्मृतोऽस्येनां कथम् ॥ (Abhijñānaśākuntalam.V.1)

[7] कामं प्रत्यादिष्टं स्मरामि न परिग्रहं मुनेस्तनयाम् ।बलवत्तु दूयमानं प्रत्याययतीव मे हृदयम् ॥(Abhijñānaśākuntalam.V.31)

[8] ततः प्रविशति नागरिकः श्यालः पश्चाद्बद्धपुरुषम् आदाय रक्षिणौ च ।(Abhijñānaśākuntalam.act VI)

[9] मालविका बकुलावलिका च पातालवासं निगडपद्यौ अदृष्टसूर्यपादं नागकन्यके इवानुभवतः।(Mālavikāgnimitram.act IV)

[10] मुषितसन्निधौ बाह्यनामभ्यन्तराणां च साक्षिणामभिशस्तस्य देशजातिगोत्रनामकर्मसारसहायनिवासान्नुयुञ्जीत । ताश्चापदेशैः प्रतिसमानयेत् ततः पूर्वस्याह्नः प्रचारं रात्रौ निवासं चा ग्रहणादित्यनुयुञ्जीत । तस्यापसारप्रतिसंधाने शुद्धः स्यात् अन्यथा कर्मप्राप्तः । (Arthaśāstra.4.8.1-4)

[11] सहजं किल यद्विनिन्दितं न खलु तत्कर्म्म विवर्जनीयम् । (Abhijñānaśākuntalam.VI.1ab)

[12] जानुक विस्रगन्धी गोधादी मत्स्यबन्ध एव निःसंशयम् । (Abhijñānaśākuntalam.act VI)

[13] अचोरं चोर इत्यभिव्याहरतश्चोरसमो दण्डः चोरं प्रच्छादयतश्च । (Arthaśāstra.4.8.6)

[14] एष नः स्वामी पत्रहस्तो राजशासनम् प्रतीष्य इतोमुखो दृश्यते । (Abhijñānaśākuntalam.act VI)

[15] भर्तारं लङ्घयेद् या तु स्त्री ज्ञातिगुणदर्पिता ।तां श्वभिः खादयेद् राजा संस्थाने बहुसंस्थिते ॥(Manusṁrti.VIII.371)

[16] पतिगुरुप्रजाघातिकामग्निविषदां संधिच्छेदिका वा गोभिः पाटयेत् । (Arthaśāstra.4.11.19)

[17]बन्दिग्राहांस्तथा वाजिकुञ्जराणां च हारिणः । प्रसह्यघातिनश्चैव शूलनारोपयेन्नरान् ॥ (Yājñavalkya sṁrti.II.273)

[18] संधिं कृत्वा तु ये चौर्यं रात्रौ कुर्वति तस्कराः। तेषां छित्वा नृपो हस्तौ तीक्ष्णमूले निवेशयेत् ॥ (Manusṁrti.IX.276)

[19] मुख्यानां चैव रत्नानां हरणे वधमर्हति । (Manusṁrti.VIII.323)

[20] चौरंप्रधाप्यापहृतं घातयोद्विविधैर्वधैः । (Yājñavalkya sṁrti.II.270)

[21] स्फुरतो मम हस्तावस्य बध्यस्य सुमनसः पिनद्धुम् ।(Abhijñānaśākuntalam.act VI)

[22] नार्हति भावोऽकारणमारणो भवितुम् ।(Abhijñānaśākuntalam.act VI)

[23] मुहूर्तं प्रकृतिगम्भीरोऽपि पर्य्युत्सुकनयन आसीत् ।(Abhijñānaśākuntalam.act VI)

Feature Image Credits: amarchitrakatha.com

Conference on Ethics Law & Justice

Watch video presentation of the above paper here:

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.