Abstract

Atman Samarpan or dedicating oneself to the worship of the almighty has been an integral aspect of bhakti and is also found in the Gita, wherein Lord Krishna preaches to Arjuna to offer every action of his to Lord Krishna. Samarpan attains a deeper meaning in the Pushtimarg sect as one is initiated through a ritual that comprises the Brahmasabandh diksha.

While Surdas has invariably been associated with the Pushtimarg sect and considered pioneer among the ashthachaapkavi, John Stratton Hawley is of the opinion that the sect used Surdas’s verses (compiled as Sursagar) in its devotional life, giving him a formal place in the liturgical system. (Juergensmeyer and Hawley, 2004) There has been much confusion about the known Sursagar manuscripts with regard to their attribution to the “real/original Surdas” and since the verses were composed orally by Surdas and written by others who heard them, it contributes to the ongoing confusion.

My contention is not to argue against the view shared by Hawley, but to rather demonstrate the different forms of samarpan expressed in selected illustrated manuscripts of the Sursagar from the Mewar court of Rajasthan. In the illustrated manuscripts under consideration, Surdas has very intricately woven this aspect of samarpan, experienced distinctly by different people, uncovering the myriad forms of devotion. The deeper implications of Bhakti poetry and devotional songs have often been understood through a feminine voice, and; the union of lovers has invariably been compared to the union of the devotee with the almighty. I believe that the analysis of samarpan textually as well as visually could lead to the discovery that this expression is in fact, aligned with the belief that lies at the core of the Pushtimarg sect.

Introduction

Surdas, one of the prominent poets of the Sagun bhakti during the fifteenth – sixteenth centuries composed and sang verses in Brajbhasha dedicated to Lord Shri Krishna which have since then been accepted and sung by the various Vaishnava sects of North India. The verses composed by him have been compiled and known as Sursagar. Surdas has been considered the pioneer poet among the ashtachaapkavi (eight seals of poets) within Pushtimarg and his verses have since then been recited by the sectarian authorities and devotees before the various images (Swarupa) of Krishna, whom they fondly refer to with the title of Thakurji (their Lord). However, the American religious studies scholar, John Stratton Hawley is of the opinion that the Pushtimarg sect used Surdas’ verses in its devotional life by giving him a formal place through initiation in the sect as one of the disciples of Shri Vallabhacharya, the founder of the Puhstimarg sect. This paper begins by stating the views shared by Hawley, who has popularly been considered an expert on Sursagar manuscripts, setting the grounds for an analysis of a certain aspect, namely samarpan (surrender) found across the manuscripts of Sursagar. Through a textual and visual analysis of selected illustrated Sursagar manuscripts from the seventeenth-century Mewar school of paintings in Rajasthan, the paper proceeds to unravel ‘samarpan’ as observed in its various forms. While Jack Hawley and Kenneth E. Bryant have extensively worked on translating the verses of Surdas and situating him within the larger corpus of the bhakti movement (Bryant, 2015);Rita Sodha has in the past explored the visual aspects of the illustrated Sursagar manuscript from Mewar largely applying an art historical approach which encompasses semiotics to decipher the text-image relationship while extending it later to the domain of authorship (Sodha, Intertextuality, Authorship and the Conundrum of Interpretation in the Sursagar Paintings of Mewar, 2003) and more recently addressing the aspects of creation, participation and consumption of the manuscripts. (Sodha, The Rationale of ‘Viewing’: Mapping the fluxed field of ‘Vision’ comprehending the Generated Meaning(s) in Illustrated Paintings, 2021) However, the objective of the present paper is neither inherently literary nor art historical although it is informed by the two approaches, nor is it my intention to contend with Hawley’s views but to rather demonstrate that this aspect of samarpanin Sursagaris aligned with the tenets of Pushtibhakti, something which has not been attempted to my knowledge before by previous scholars.

I

Surdas (b.1479 – d.1584) was a poet, saint and singer who composed verses in Brajabhasha in the form of pada (literally foot or pace) devoted to Shri Krishna. His contribution through these verses has been significant to the spread of the medieval period bhakti movement in North India. Surdas was considered to be blind and there have been contrasting stories regarding how and when he turned blind. (Hawley, 1984, pp. 248-266) Therefore, the tradition which he inherited was largely an oral one. Surdas never wrote himself but composed and sang before his Lord and it was the listeners who recorded the songs they heard in their own scripts and sometimes they wrote after an interval, employing their own intelligence where memory failed leading to different versions. (Bahura, 1984) The manuscripts which have been discovered from the time since a century or so post the poet’s demise, appear to be collections that are independent of one another. Therefore, Sursagar is not a linear text or a continuous narrative, but a collection of individual verses which although devoted to Krishna are not organised in one particular way but in a variety of ways – by raga, by theme, and only sometimes by the progression of Krishna’s life story. The oldest Sursagar manuscript written in Fatehpur in 1582 A.D. contains 239 poems attributed to Surdas and only later does the collection assume oceanic dimensions, thus the designation Sursagar. (Hawley, A Storm of Songs: India and the Idea of the Bhakti Movement, 2015, p. 24)It is, however, misleading to think of the poems of Surdas as constituting a text because in some cases, the poems once attributed to other lesser poets have eventually been absorbed into the Sursagar.

The chaurasivaishnavan ki varta is a collection of eighty-four varta (stories) in Brajbhasha of the chief Vaishnav disciples of Vallabhacharya, the founder of the Vallabha/PushtimargSampradaya and these stories are not mere legends but are considered to be true accounts of actual persons and real-life episodes which played important roles in unfolding of Vallabhacharya’s spiritual revelation. Gokulnathji, the grandson of Vallabhacharya is credited for gathering the varta while Harirayji, the great-grandson of Vitthalnathji (second son of Vallabhacharya) organised the varta to their present form. Among the ashtachaapkavi, four of the poets including Surdas were placed within the chaurasivaishnavan ki varta and are considered to be the disciples of Vallabhacharya and initiated in the sect through the Brahmasambandh diksha while the other four poets were placed under the 252 (do saubaavanVaishnavan ki varta) as disciples of Vitthalnathji. However, Hawley is of the opinion that this ashtachaap edifice represents a major distortion of history and that in each case it seems to have taken quite some “manoeuvering” to make them into Vallabhites. (Hawley, A Storm of Songs: India and the Idea of the Bhakti Movement, 2015, p. 183) He states:

“This effort to rewrite history is important not only because it throws a particular spin on the question of how a bhakti movement comes into being. If bhakti is a vernacular groundswell whose major medium is poetry, especially poetry of the sort that would typically be sung, then this effort to constrain it within sectarian channels – take a poet’s agency and transfer it to his supposed guru – does a fundamental disservice to the contagious reality of bhakti itself. It harnesses the energy of song for theological and institutional purposes that are foreign to its inner spirit.” (Hawley, A Storm of Songs: India and the Idea of the Bhakti Movement, 2015, p. 183)

He further clarifies that in 1640 Surdas’ verses were already called an ocean, Sursagar but that there was nothing specifically Vallabhite about it:

“One can admire the ingenuity with which the authors of the varta and its commentary approached the task of incorporating Surdas retrospectively into the Vallabha sampradaya, and one can appreciate how satisfying it must have seemed to members of the Vallabhite community to see that Surdas was one of us, participating in the devotional intensity that became such a notable and praiseworthy feature of the Pustimarg, but we must remember, on the other hand, that the facts of the matter were otherwise.” (Hawley, A Storm of Songs: India and the Idea of the Bhakti Movement, 2015, pp. 184-85)

“In a similar way, anthologists working outside the Pustimarg – and sometimes earlier – show no awareness that Sur’s poetry ought to be aligned with compositions attributed to poets whom the Vallabhites claimed as belonging to the astachap.” (Hawley, A Storm of Songs: India and the Idea of the Bhakti Movement, 2015, p. 185)

Interestingly, the Vallabha Sampradaya is not the only one to be incorporating Surdas within its liturgical discourse. Hawley brings to our notice how Raghavdas who worked as an anthologizer of bhaktas, based on the model of the Bhaktamal of Nabhadas, places a considerable group of singers and poets such as Hit Harivams, Hariram Vyas, Keshavdas, Paramanandadas, the Sanskrit poet Bilvamangal and Surdas under the Nimbarka Sampradaya. Hawley then states how the Vallabhite claim to Surdas is no stronger than Raghavdas’s proposal and that based on historical grounds, there is no accurate way to align the historical Surdas or Bilvamangal with any sampradaya whatsoever. (Hawley, A Storm of Songs: India and the Idea of the Bhakti Movement, 2015, p. 135)

Before I attempt to provide a few answers to the claims made by and the questions raised by Hawley, let us begin by having a basic understanding about the Pushtimarg Sampradaya. Pushtimarg or as translated literally, the path of grace was founded by Vallabhacharya and for the same reason is also called Vallabha Sampradaya. Vallabhacharya was born into a family of Telugu Brahmins in a place by the name of Champaran located in Chhattisgarh and it is believed that at midnight on the eleventh day of the Shravan Shukla paksha Ekadashi in the year 1494 A.D., Shri Krishna appeared before Vallabhacharya and revealed to him directly the means by which the jivas might be cleansed of their faults which is reverberated in the Siddhant Rahasyam composed by Vallabhacharya. The philosophical system prevalent in Pushtimarga is Shuddhadvaita or pure non-duality and where Krishna is considered to be saguna (possessed of qualities). Damodardas Harsani was the first disciple of Vallabhacharya, initiated into the sect through a rite of passage (mantra diksha by taking Brahmasambandha) which is a necessary step towards the seva of the swarupa (serving the image of Krishna). The seva established by Vallabhacharya is that of the image of Krishna who is treated as the divine cowherd of Braj throughout the day from early morning to late evening and throughout the various seasons and numerous festivals of the year. Raga, bhoga and shringara are crucial to the seva of Krishna and form the basis for the ritualistic and performative practices observed within the sect. However, the tenets of pushtimarga are ashraya, samarpan and sharnagati (shelter/resort, surrendering oneself and seeking refuge in the lotus feet of Shri Krishna) which eventually give way to the ritualistic practice of performing seva. The dikshamantra through Brahmasambandha that one recites during the time of initiation is that of surrendering oneself along with one’s wealth and possessions to Lord Krishna, thereby entitling the devotee to perform seva and it is believed that even if momentarily the devotee might forget to remember Lord Krishna, Krishna will never forget to take care of his initiated devotees who have no other abode beside Krishna’s lotus feet. SiddhantaRahasyam by Vallabhacharya, therefore, gives the samarpanaupadesha to the initiated bhakta who has performed atman-nivedanam or self-submission to Shri Krishna asking the devotees to dedicate everything they do and consume to Shri Krishna:

निवेदीभिःसमर्प्यैवसर्वम्कुर्यदइतिस्थितिः

At the outset of every task to be undertaken by the devotee, Shri Krishna must be the one to whom it must be dedicated: तस्मतादौसर्वकार्येसर्ववस्तुसमर्पणम (Goswami, 1998, pp. 63-70) Furthermore, in the treatise composed by Shri Harirayji titled Shikshapatra which is a doctrinal treatise, Vallabhacharya preaches to the devotee:

अतःशरणमात्रमहिकर्तव्यमखिलमततः।

यदुक्तमतातचरणेरीतिवाक्यादभविष्यति॥२४॥

Shri Krishna is my shelter (ashrayasthaan) and gives the ashtakshar diksha of श्रीकृष्णःशरणममम to the devotee to recite. He further also states that Satsang (good/right company of fellow devotees), Shri Krishna’s smarana (remembrance) and sharnagati (seeking his shelter) are what the devotees must use their minds for:

सत्संगकृष्णस्मरणशरणागतिसाधनेः।तदभावेकृतिःसर्वायतोवैयर्थ्यमेतिहि॥२॥ (Panchasara, 2012, pp. 17-21)

In pushtimarga, bhava is sadhan rupa, Pramey is God himself and Shri Krishna’s seva is pramanarupa, which later becomes falarupa which means that sentiment is the means to understand God, Krishna himself and his seva is evidence or rather the manifestation of the initial sentiment. (Panchasara, 2012) Therefore, bhava or the emotional sentiments are at the core of Pushti seva and Pushti bhakti through which the devotees experience multiple emotions towards their beloved Lord through daasya bhava (servitude), saakhya bhava (friendship), vatsalya bhava (maternal love) and madhurya bhava (romantic love). The seva of the deity throughout the year incorporates these diverse sentiments through the celebration of festivals wherein one particular sentiment surfaces predominantly over the others; for instance, during the festival of Holi, saakhya bhava is predominant, owing to which, meethigaari (sweet teasing) are sung before Krishna reminding him of his sakhas (friends) in Braj who conspire with him to drench the gopis and Radha in Holi colours. However, the sthaayi bhava within Pushtimarga is always daasya bhava as one never forgets that one is only a sevak/dasa serving one’s beloved Lord, Thakurji. These sentiments are pivotal to performing seva as they enable the devotee to provide ananda (eternal bliss) to Krishna by partaking in his Leela, thereby experiencing ananda themselves. Since Krishna Leela has been performed by Krishna in Braj, creating the Braj bhava or a conducive atmosphere which makes Krishna feel at home in Braj is at the core of Pushtimarg seva. With this understanding, let us now examine a few illustrated manuscripts of Sursagar.

II

Although the Sursagar is vast comprising verses arising from several themes, a rough categorisation can be made of verses belonging to – (a) Krishna Leela, (b) Vinay Padavali, (c) Ramakatha and (d) Sudama Charitra. The first set of the Mewar Sursagar paintings appears to be commissioned by Rana Jagat Singh I of Mewar (1628-1652 A.D) and demonstrates the diverse themes prevalent in the verses. (Sodha, Intertextuality, Authorship and the Conundrum of Interpretation in the Sursagar Paintings of Mewar, 2003) I am considering three illustrated Sursagar manuscripts which demonstrate samarpan but in varied forms.

(Figure 1: Credit: Government Museum, Udaipur – Vrindavan Vihar, Sursagar, Mewar, seventeenth century)

रागदेवगांधार

उरपरसोभतहैंससिसात।

सोवतहुंतीकुंअरराधिकाचमकउठिअधरात।

खंडखंडकेगीर्योतेंसपनकिन्याकोभात।

करीबहूँरूपवाश्यपंथनेआयोजलजात

बिद्युबिनुलेपसतसंगीसिवसतमोहिगाता।

सूरदासप्रभुकोकहेउपमास्यामकहेंगेबात।

Radha is sleeping and dreaming that she is suddenly adorned by seven moons. The sleeping Radhika wakes up, startled, wondering what were those fragmented pieces (like brothers of the moon – perhaps the stars) that fell upon her. Or was it the son of the ocean – the moon donning varied guises while making its movements across the sky? She narrates her dream to her friend – perhaps it was the guise of Shiva that the moon had adorned, which scattered and fell in fragments and pierced me through the arrows of passion. Surdas exclaims addressing Krishna – who besides you, Shyam can save the Earth under such morbid circumstances!

The pictorial plane depicts Radha sleeping in her chamber and waking up startled narrating her dream to her friend. Meanwhile, another friend rushes to seek Krishna’s refuge at this fatal moment. The moon, Shiva and Kamadeva are depicted as symbols in the receding space of the painting. Surdas is depicted in a corner at the bottom of the pictorial plane as the sutradhar or the composer of the verse which is uniformly observed in all the Mewar Sursagar paintings. It is also important to note that Surdas changes his voice and utters the verses in the voice of another person – often gopi, Yashoda, Radha, Nanda and the sakha/gopa. What is interesting about this verse is that it is actually describing an amorous event that unfolds in order to bring Krishna and Radha together which is confirmed visually by the presence of Kamadeva. However, the other implication of the verse is that since the gopi/sakhi naturally seems to have rested her faith in Krishna, by submitting herself to him, she immediately sought him to seek his refuge. This verse can then be taken to evoke madhurya bhava.

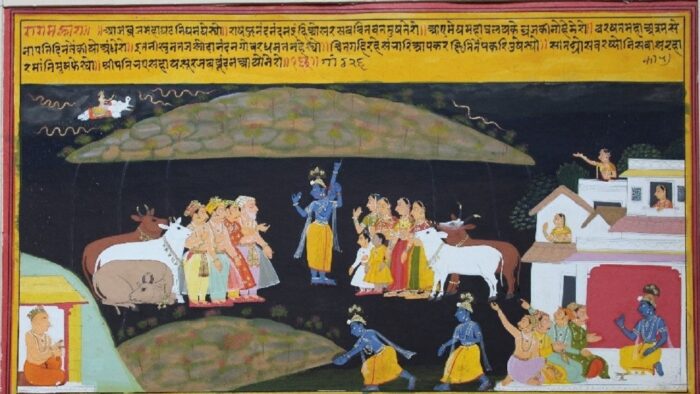

Figure 2: Credit – Government Museum, Udaipur – Govardhan Dhaaran, Sursagar, Mewar, Seventeenth century)

रागमल्हार

आजुब्रजमहाघटिनघनघेरो।

राखिस्यामअबकेंइहिअवसरसबचितवतमुखतेरो।

कोटिछयानबेमेघबुलाएआनिकियोब्रजडेरो।

मुसलधारटटेचहुँदिसतैहवैगयोदिवसअँधेरो।

इतनीसुनतजसोदानंदनगोवर्धनतनहेरो।

लियोउठाइसैलभुजगहिकैमहितेंपकरिउखेरो।

सातदिवसजलबरसिसिरानेहारिमानिमुख्यफेरो।

सूरसहाइकरीनिजभुजबलबुंदनआयोनेरो।

Braj is surrounded by an overcast of dark grey clouds, the gopi bespeaks everyone else’s mind by seeking Krishna’s refuge. Describing the dreadful atmosphere, she says that ninety-six crore clouds have overcast their shadow upon Braj and a fierce downpour is inevitably taking place in all four cardinal directions making it seem as if the day has turned into night. Upon hearing this much, the son of Yashoda, Krishna embraces the mountain Govardhan and lifts it, uprooting it from the Earth. For seven days it poured incessantly, eventually leading to the defeat of Indra who turns away his face and walks away. Surdas says that not a drop of rain could touch us since we were under the shelter of Krishna’s strong arms. The verse seems to unfold pictorially from the bottom right of the pictorial plane wherein the people of Braj seem to be anxiously pointing towards the burgeoning grey clouds laden with rain and coming to seek help from Krishna. The verse progresses as we notice Krishna lifting Mountain Govardhan from the base and lifting it with his arms, eventually holding it atop his little finger, underneath which the people of Braj along with the cows seek shelter. Once again, we see the aspect of samarpan surface through this verse where the people of Braj have no other ashray or refuge besides that of Krishna and have submitted themselves to him under such dire circumstances.

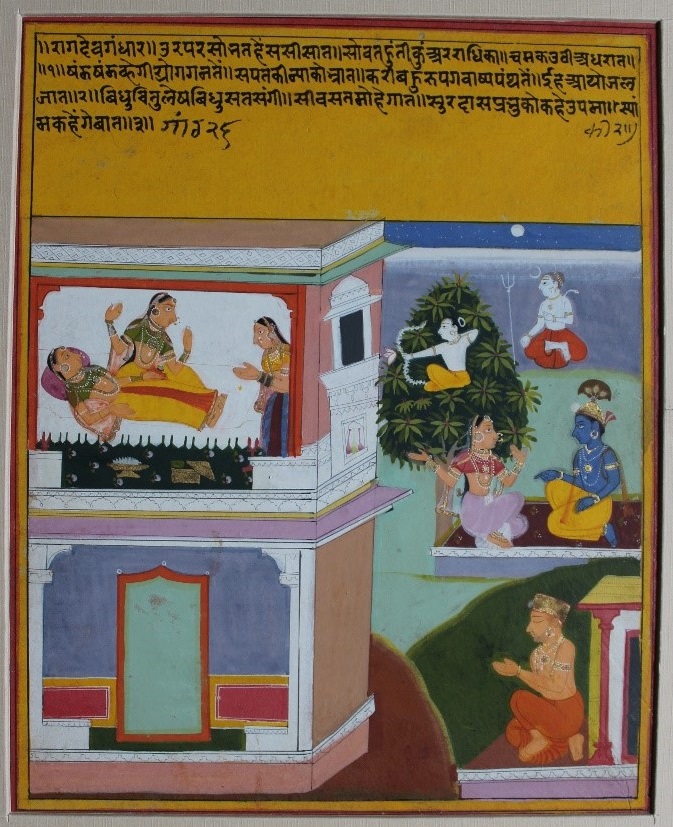

(Figure 3: Credit: Government Museum, Udaipur – Vinay Padavali, Naam Mahima: AtmaNivedan, Sursagar, Mewar, Seventeenth Century)

रागधनाश्री

जिनकेउपजतदुखक्यूंनकाटना।

प्रथमअषाढ़कंचनजैसेकपिकुलनिरखीउपाटत।

जैसेकीरबकीसानंजतनकरीआनघासगहीकाटत।

पींछेसहसगुनोकेनिपजतखसमखुशीसेलाटत।

ज्यूँकीलकीलामीनतनचाहतएसोरहोप्रभुकाटत।

सुनोस्यामसिंधुबघतहैसुरखारकीनेपाटत।

Surdas makes an appeal to his lord, Krishna: Why don’t you eradicate misery from the lives of those who suffer? Just as catching the glimpse of the grains that listen like gold during the onset of the Ashadha month, monkeys grab them away. Just as parrots and cranes peck away the drier grass to make their nests, later on seeing his harvest a hundred times better, the farmer gets overjoyed. Just as the crane desires to eat the body of the fish, dear Lord, cease our sorrows. Listen, Shyam, the river (of pain) is rising, so why don’t you separate salt (misery) from it?

Pictorially, we observe all the similes of the verses rendered visually – such as the monkey collecting the grains, the crane flying towards the fish in the water, the salt being separated from water and the farmer rejoicing his harvest produce. Interestingly, Surdas is rendered twice within the pictorial plane – once as the composer and the second time as the active voice of the verse. Krishna is also observed here in his nascent Vishnu form with chaturbhuja and ayudha held in each arm, seated on a lotus asana which only reinforces the dasya bhava of this verse. Surdas in all humility has surrendered himself to Krishna seeking his sharnagati and praying to his Lord to set him free from the sorrows of his life.

III

Now, to address Hawley’s claim of Surdas being deliberately incorporated into the Pushtimarg sect through the written evidence as observed in the varta, I would only like to state that Surdas holds an important place within Pushtimarg sect and outside of it. Even if he was, as Hawley argues, incorporated into the sampradaya, his composed verses have never remained confined to one particular sect, but have rather been shared among the various Vaishnav sampradayas in Braj owing to a commonly shared sentiment of love towards Radha and Krishna either in their duality or non-duality. In fact, Hawley states how the Gaudiya Sampradaya and the Pushtimarg Sampraday have similar theologies of devotional freedom and radical grace but he continues to have a problem with the Vallabha Sampradaya, their claim to the worship in the temple atop mountain Govardhan and the incorporation of Surdas within their sect.

However, through an analysis of the illustrated Sursagar manuscripts and with an understanding of the beliefs core to Pushtimarg, we may be able to agree upon the fact that the key aspects of samarpan, ashraya and sharnagati can be experienced through the seva of Krishna as well as the recital of the padas from Sursagar in diverse forms. If we observe the Sursagar verses closely, we realise that Surdas dons several voices of the characters central to Krishna’s life whether they be that of – Radha, Nanda, Yashoda, Balaram, his sakhas/gopas or the gopis but the verse eventually ends with the characteristic (Chaap) signature of Surdas in his own voice. The same is the case when a pushtimargi devotee performs his/her Thakurji’s seva as he/she dons several roles and experiences various sentiments as that of a mother, a friend, a confidant or a lover throughout the year by partaking in the festivals as well as the day-to-day rituals and thereby being a part of his leela while continuing to remain a devotee (dasa/sevak) underneath all those personifications akin to Surdas signing off the verse in all humility of a devotee.

Bibliography

Bahura, G. N. (1984). Padas of Sursagar. Maharaja Sawai Man SIngh II Memorial Series, 6, viiff.

Bryant, K. E. (Ed.). (2015). Sur’s Ocean: Poems from the Earthly Tradition. (J. S. Hawley, Trans.) USA: Harvard University Press.

Goswami, S. (1998). Pushti Path (Gujarati). Junagadh: Shri Purushottam Pushtimargiya Charitable Trust.

Hawley, J. S. (1984). Sur Das: Poet, Singer, Saint. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Hawley, J. S. (2015). A Storm of Songs: India and the Idea of the Bhakti Movement. USA: Harvard University Press.

Panchasara, R. (Ed.). (2012). 41 Shikshapatra Saarsanchay. Rajkot: Pushti Asmita Sanvardhan Kendra.

Sodha, R. (2003). Intertextuality, Authorship and the Conundrum of Interpretation in the Sursagar Paintings of Mewar. In S. Pannikar, P. D. Mukherjee, & D. Achar (Eds.), Towards A New Art History: Studies in Indian Art (pp. 211-220). Delhi: D. K. Printworld (P) Ltd.

Sodha, R. (2021). The Rationale of ‘Viewing’: Mapping the fluxed field of ‘Vision’ comprehending the Generated Meaning(s) in Illustrated Paintings. In G. P. Krishnan, & R. R. Kulkarni (Eds.), Ratna Dipa: New Dimensions of Indian Art History and Theory (pp. 123-130). Delhi: Agam Kala Prakashan.

Feature Image Credit: Government Museum, Udaipur

Watch video presentation of the above paper here:

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.